The JEC Chair Brady (R) writes: “While the unemployment rate has fallen it doesn’t tell the true story about stagnant paychecks and Americans struggling to find full-time work.” He then calls for passage of Keystone-XL as part of the remedy.

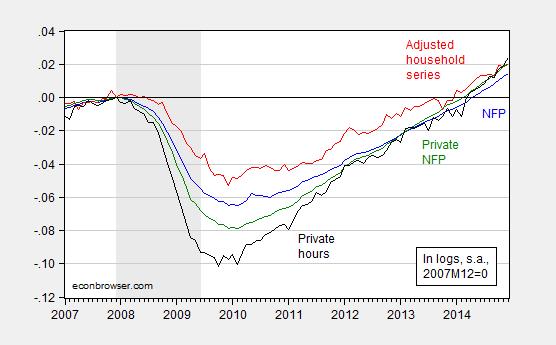

Figure 1 depicts the evolution various indices of employment growth — nonfarm payroll, private payroll, private hours, and nonfarm payroll estimate derived from household survey.

Figure 1: Log nonfarm payroll employment (blue), household series adjusted to NFP concept (red), private nonfarm payroll employment (green) and private hours (black), all normalized to 2007M12=0. Source: BLS, and author’s calculations.

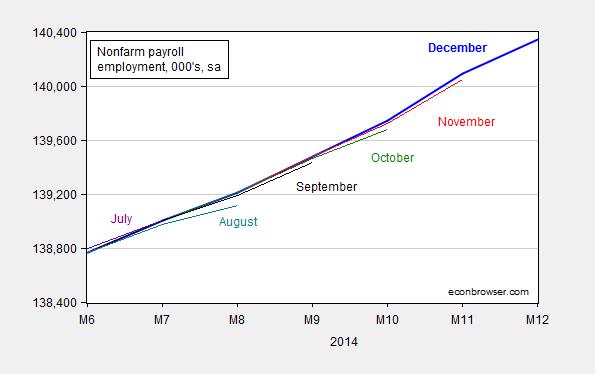

Figure 2 shows that each month’s estimate has been revised upward since June.

Figure 2: Nonfarm payroll employment for December (blue bold), November (red), October (green), September (black), August (teal), July (purple). Source: BLS.

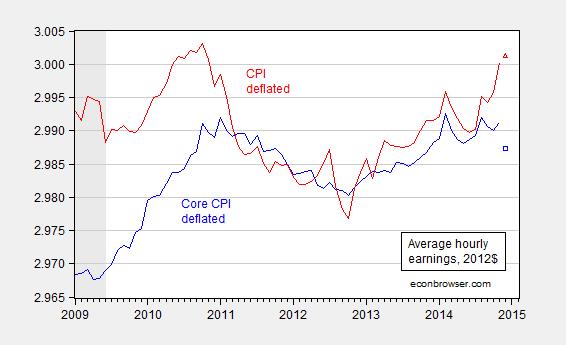

A major them of the articles covering the release have focused on wages, highlighting the negative growth in the last month. It’s useful to remember that real wages matter as well. Here the trend is more ambiguous.

Figure 3: Log real hourly earnings in 2012$ for production and nonsupervisory workers, deflated by Core CPI (blue), and by CPI (red). Observations for December calculated using Bloomberg consensus for CPI and Core CPI as of 1/11/2015. Source: BLS series AHETPI for earnings, BLS, Bloomberg, and author’s calculations.

These data suggest little inflationary pressures arising from rising wages.

Menzie wrote:

These data suggest little inflationary pressures arising from rising wages.

Duh? Inflation is a monetary phenomenon. This is why there is so much confusion in economic education.

Ricardo:

Duh? You may not be aware because you don’t work, but wages are paid in money.

Amity Sshlaes on James Grant’s book The Forgotten Depression–1921: The Crash That Cured Itself:

“Rueff’s Law, the theory of French economist Jacques Rueff (REW-eff). Rueff noted that, when wages were permitted to rise relative to prices, unemployment moved up, too. To Rueff and others, by the way, that seemed as obvious as Keynesianism does to Janet Yellen. “The astonishing thing is not that this relationship exists,” wrote Rueff, “but that it should astonish anyone.” [my emphasis]

Interesting theory.

In the US since 1965 the correlation between the change in real average hourly earnings and the unemployment rate is minus -0.16.

Does not seem to be a very strong relationship.

P.S. 1965 is the first year the data is readily available.

Hmm, let’s see. When did oil prices collapse? And since then, actual has been coming in over projected? You want to take a guess about what’s going to happen to IMF GDP forecasts compared to actual?

Now, I think there’s an interesting debate coming up. Larry Summers and Scott Sumner have both postulated that the labor force participation rate will not recover, and therefore secular stagnation will arise not from a lack of aggregate demand (“Secular Stagnation 1.0”), but rather a labor shortage (“Secular Stagnation 2.0”).

You can’t have it both ways. You can’t have a labor shortage without wage increases. So it’s one or the other, unless you think GDP won’t grow very fast. And then I would counter that I don’t understand why Germany can have a labor force participation (LFP) rate 7 pp higher than ours, and Switzerland 12 pp higher than ours, when simultaneously we have a demand for labor and no supply response in either price or quantity.

And by the way Menzie, if oil prices stay low, we’re going to see a blue collar employment boom unlike anything we’ve seen since the 1960s. That’s what my models suggest.

Yes, but you miss the main thing these data report, which is no secular stagnation. The great political scientist Samuel Huntington talked about the strange obsession with “decline” in the USA. Every 30 years or so the public become obsessed over national decline. In reality, the USA always prevails to an even a stronger position after all the gnashing of teeth is over.

I see the secular stagnation hypothesis as a part of this declinist rhetoric. The data absolutely in no way shows anything other than a massive standard recession, that was antagonised by pro-cyclical policy. So, it took a long time to come back to normal. But there is no need to create grandiose doom-day scenarios of national decline. Boom and bust, that’s all….

See Huntington here:

http://www.li.suu.edu/library/circulation/Stathis/HuntingtonDeclineorRenewalPart1Fall11.pdf

Factoid of the day: Low oil prices, purely from the price effect, will add 0.5% to US GDP in 2015.

Steven Kopits you wrote,

“Factoid of the day: Low oil prices, purely from the price effect, will add 0.5% to US GDP in 2015.”

Is that all? Can’t you find a way to make the projection larger?

I remember the projection by Macro Advisers, that Menzie brought us, that projected a .6% decrease in GDP by the much smaller sequester. Yes, the number did not come true, but the good intention is important.

Ed

Ed –

That’s the straight price effect: $50 x 5 mbpd x 365 = $91 bn / $17 trn = 0.5%. That’s what you can bank straight into national accounts without any sort of multiplier

Keep in mind we import a lot less than we used to, and that the US is not as oil intensive as it once was. Lower prices today are a negative to the oil sector, so the benefit is just the amount of net imports.

The multiplier effect is much larger of course. If we view in volume terms, GDP growth is normally change in oil consumption + efficiency gain. You can bank a 1% efficiency gain this year, plus, say 2.6% oil consumption growth. So figure growth in the high 3%’s by this measure. Gut says we might be over 4% this year, though.

That boost from import price reduction would be to nominal GDP.

To get more real GDP, the consumer has to spend the savings on some other good or service, and at least part of the value of that good or service has to be domestically produced, and it has to be additional production not merely driving up the prices of previous production levels.

Which will all happen, but it’s not an automatic one-for-one.

And actually even the boost to nominal GDP from an import price decline isn’t automatic one-for-one – some portion will be spent on other imports.

GDP = C + I + G + (X-M)

So, let’s assume I spend all my savings on imports of other stuff. In dollar terms, that increases “C” while holding “M” constant. That should increase GDP, unless I have my math wrong.

The exception is if the savings are directed towards the capital account, ie, paying down external debt, for example. Since the cost savings accrue principally to consumers in after-tax dollars, the marginal propensity to consume should be very high unless the government institutes a tax increase to repay debt faster. It is the equivalent of a progressive tax cut, ie, it helps low wage earners more as a percent of income.

Other than that, I believe a reduction in oil import expense ends up right in the GDP account, but no doubt Menzie will disabuse me if I have it wrong.