Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution written by Joshua Aizenman (USC and NBER), Yothin Jinjarak (Victoria Business School), and Huanhuan Zheng (Chinese University of Hong Kong). This post is based upon the paper of the same title.

China has been a prime example of export-led growth that has benefited from learning by doing, and by adopting foreign know-how, supported by a complex industrial policy. Arguably, a modern version of mercantilism has been at work (Aizenman and Lee 2008, World Economy). The rapid growth, growing trade, and current account/GDP surpluses in the 2000s had occurred in tandem with massive hoarding of international reserves (IR) combined with massive sterilization of expending trade surpluses and financial inflows. The global financial crisis (GFC) of the late 2000s put an abrupt end to the Chinese export-led, growth-cum-large current-account surplus trajectory. A legacy cost of Chinese policies during the 2000s has been its skewed external balance — long on low-yielding foreign assets [mostly international reserves], and short on high-yielding assets [mostly large liabilities associated with past net FDI inflows to China]. While China’s net external financial assets in 2013 was about 20% of China’s GDP, the real net return on these assets was negative. The low return on Chinese foreign assets is bad news, especially considering the rapid aging of China’s population.

A way of mitigating the adverse consequences of Chinese legacy external balance sheet exposure is external rebalancing, that is “swapping” overtime some of its international reserves with higher yielding foreign equities and outward Chinese FDI. Indeed, China embarked on diversifying its holdings of dollar IR by channeling surpluses into a sovereign wealth fund (SWF), encouraging outward foreign direct investment in tangible assets, and offering much higher expected returns. The outcome has been growing FDI in the global resource sectors and infrastructure services, especially in commodity and mineral exporting countries, which includes developing countries and emerging markets in Africa and Latin America. After the financial crisis in 2008, China embarked on large bilateral currency-swap agreements with other countries. Most of the swap-lines offered by China have been to commodity countries, developing and emerging market economies.

Against this background, Aizenman, Jinjarak and Zheng (2015) takes stock of what may be the new chapter of Chinese-outward mercantilism, which is aimed at securing a higher rate of returns on its net foreign asset position, leveraging its success in becoming the global manufacturing hub. We conjecture that in the aftermath of the GFC, China has bundled outward FDI with its finance dealing (lending, swap-lines, trade credit), its trade and foreign investment (including exports of Chinese capital products and labor services), and leveraging its growing market clout. This bundling strategy has been mostly applied to developing and emerging market economies, and to “commodity-countries.” During the GFC and its aftermath, China increased rapidly and in tandem its outward FDI, swap-lines, imports and exports to the selected countries. Such a bundling strategy is consistent with Adams and Yellen (1976, QJE): bundling as a manifestation of market clout in which the bundling party leverages its market powers aimed at increasing its surplus. Accordingly, China may use its market power in the provision of “swap and lender of last resort,” supplying capital goods, and infrastructure services to its trading partners.

We find that Chinese exports of manufactures and imports of commodities to its trading partners are positively associated with the outflows of FDI to the recipient countries. The provision of the RMB swap-line is positively associated with the size of Chinese bilateral trade with the swap-line recipient countries. In addition, small countries tend to be the recipients of the RMB swap-line. Focusing on Chinese Greenfield FDI abroad and distinguishing between the FDI outflows into tradable sectors, nontradables sector, and natural resources we find that Chinese trade influences the natural resources sector FDI. Exports of manufactures are negatively associated with FDI outflows while the effects of commodities imports are positive. The association between Chinese FDI outflows in the natural-resources sector and commodities imports has become stronger since the GFC. The positive association between Chinese-outward FDI and commodities imports increases with the provision of RMB swap-lines to China’s trading partners. The influence of RMB swap-lines is especially large on the Chinese-outward FDI in the natural resources sector. The overall findings are supportive to the conjecture that in the aftermath of the GFC, Chinese-outward FDI is bundled with trade and financial linkages, thereby increasing the country’s influence in the international markets, and securing its long-run access to a stable supply of commodities.

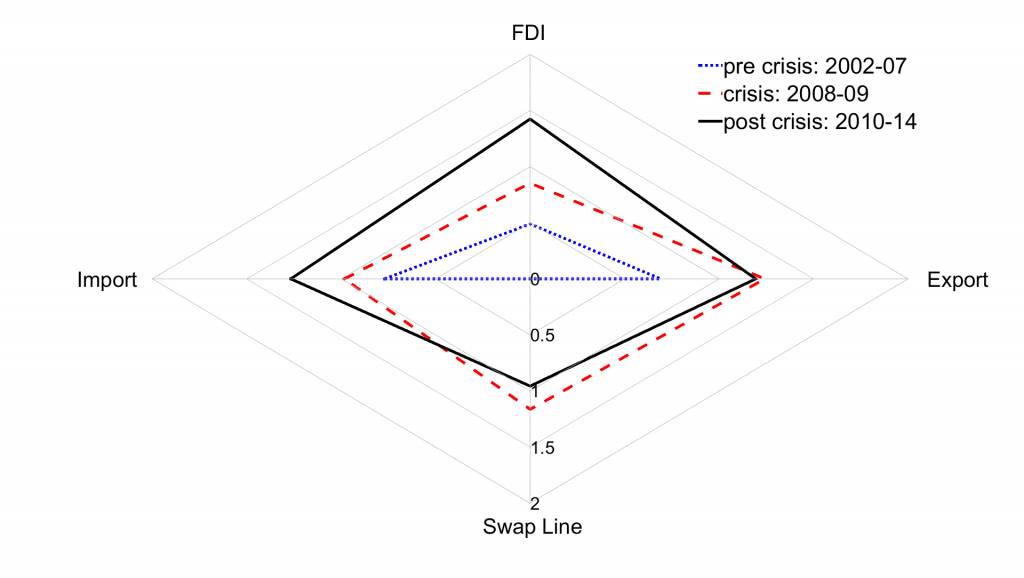

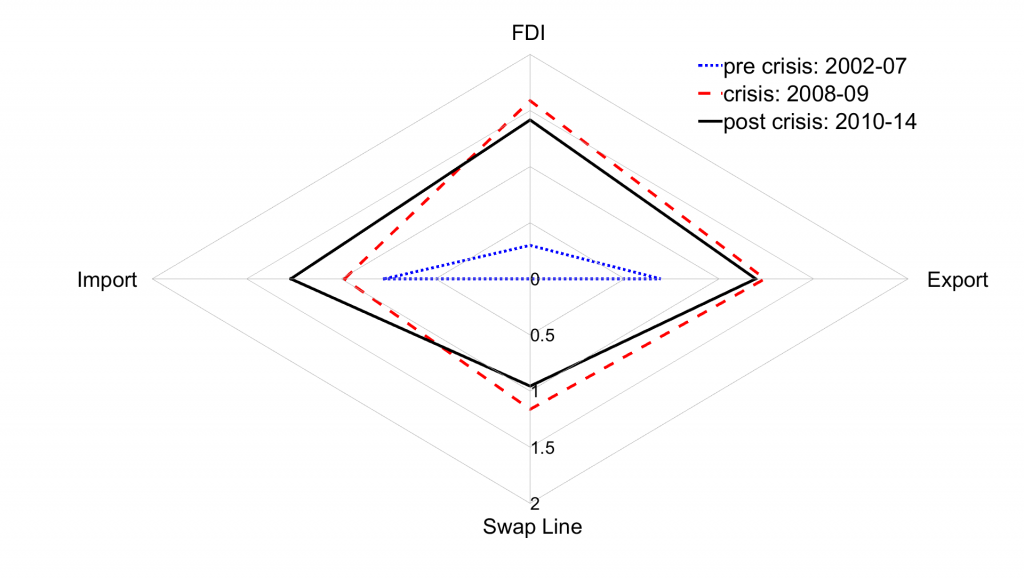

Figure 1 shows a heat map of average Chinese bilateral trade, outward FDI, and RMB swap-lines as a ratio of a recipient country’s GDP in the sample. Figure 2 overviews the relationship between Chinese FDI, trade, and swap-lines. The diamond chart plots, based on bilateral data, of Chinese FDI, exports, imports, and swap-lines, all measured as a ratio of recipient country’s GDP and weighted by the sample means. The dotted, dashed and solid lines plot, respectively, the statistics before, during and after the 2008–09 Global Financial Crisis. The diamond charts indicate concurrent and significant surges in Chinese-outward FDI, swap-lines, imports and exports to the selected countries.

Figure 1.A: China’s Greenfield FDI

Figure 1.B: China’s Aggregate FDI

Figure 1.C: China’s Bilateral Trade

Figure 1.D: RMB Swap-lines

Figure 2.A: Relationship between Chinese Greenfield FDI, Trade, and Swap-lines. The diamond chart plots, based on bilateral data, of Chinese FDI, exports, imports, and swap-lines, all measured as a ratio of recipient country’s GDP, weighted by the sample means. The dotted, dashed and solid lines plot, respectively, the statistics before, during and after the Global Financial Crisis. The recipient countries are listed in Aizenman, Jijarak and Zheng (2015).

Figure 2.B: Relationship between Chinese Aggregate FDI, Trade, and Swap-lines. The diamond chart plots, based on bilateral data, of Chinese FDI, exports, imports, and swap-lines, all measured as a ratio of recipient country’s GDP, weighted by the sample means. The dotted, dashed and solid lines plot, respectively, the statistics before, during and after the Global Financial Crisis. The recipient countries are listed in Aizenman, Jijarak and Zheng (2015).

The willingness of China to extend credit lines and invest in countries with histories of default raises concerns about the growing exposure of China to sovereign defaults, and the risk of partial nationalization of its outward FDI assets. One should keep in mind, however, that some Chinese lending to commodity countries is secured by “in kind” long-run payment in the form of oil flows and other commodities to China. Arguably, Chinese outside exposure may be also partially hedged by the growing dependence of some developing countries on Chinese infrastructure services needed to maintain their upgraded rail system, and the growing importance of China as the prime destination of their imports (and for some, their dependence on China as their only “lender of last resort”). While it is pre-mature to estimate the returns on this bundling strategy, the outcome has been increased access of emerging Africa, Asia and Latin America to improved infrastructure services, co-financed and constructed with the help of Chinese capital goods and knowhow, and co-paid by the growing exports of commodities and minerals to China. The proposed formation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, in which China would be the main shareholder may be viewed as a follow up of this bundling strategy.

Figure 1. Chinese Outward FDI, Bilateral Trade, and RMB Swap-lines.

The heat maps plot sample means of greenfield FDI, aggregate FDI, bilateral trade and RMB swap-lines as a ratio of recipient country’s GDP; darker colour corresponds to higher intensity.

This post written by Joshua Aizenman, Yothin Jinjarak and Huanhuan Zheng.

In China, it seems, work, for the masses, is the important end result.

And, of course, raising the masses living standards a little in the process helps.

Menzie,

Thanks, this is a very interesting and informative post.

My only frustration is once again economists misuse language and change the meaning of words. The article is not about Chinese mercantilism but about Chinese imports-exports. China is very mercantilist but not because it has an export based economy. It is mercantilist because the government follows a path of crony socialism and accumulation of commodities (especially gold) thinking that this hoarding will in some way make them wealthy. Actually China’s mercantilism counters Chinese trade by locking resources into non-income producing hoarding.

It seems that the writers of this article are actually attempting to make the case against China’s challenge to the international reserve status of the dollar. China is lending to countries that cannot get loans from the IMF and World Bank because they will not comply with environmental requirements that actually reduce profitability. China is lending to emerging economies and in the agreements locking in access to commodities that will support its export based economy (not mercantilism).

Since I just returned from Australia it is interesting to see how closely aligned China is with Australia on the maps. I was aware of this be the combination of my trip and this article simply focuses on the issue. I spend a number of days in Newcastle whose port is the number one exporter of coal in the world. The transport ships are lined up 30 deep at times waiting for their loads to transport coal to Asia, especially China and Korea.

China is growing and the influence of China is growing because they are more capitalist in their international trade than the US and Europe who are constrained by political fetters like radical environmentalism.

Ricardo, it seems that the authors definition closely matches the common definition as expressed in e.g. Wikipedia:

Mercantilism was an economic theory and practice, dominant in Europe from the 16th to the 18th century, that promoted governmental regulation of a nation’s economy for the purpose of augmenting state power at the expense of rival national powers. It is the economic counterpart of political absolutism. Mercantilism includes a national economic policy aimed at accumulating monetary reserves through a positive balance of trade , especially of finished goods.

Seems to me that this fits China quite well.

http://hallofrecord.blogspot.com/2007/09/why-china-subsidizes-us.html

Bruce,

You might find it interesting that Japan is now the major purchaser of US Treasury debt.

China does not subsidize the US by buying US bonds. China receives dollars when they sell goods to the US. Dollars must be spent in the US or traded at a loss with someone else who will ultimately spend them in the US. For China the best return on their supply of dollars is to buy US bonds. They can park their dollars and receive interest – granted it is low today. US bonds and US hard assets are just about the only outlet the Chinese have for redeeming their dollars.

Repatriating foreign direct investment (FDI) through nationalization of foreign assets sounds like imperialism in sheeple’s clothing.