When Technocrats Are Pushed Aside

Nearly 56 years ago, with the beginning of the second Five-Year Plan, Chairman Mao called for a “Great Leap Forward”. The objective was rapid development of the agricultural and industrial sectors in such a way as to catch up quickly with both the Soviet Union and eventually the West. A focus was on use of mobilization by political means of large amounts of labor in order to circumvent the need for imported inputs including machinery.

Political mobilization as a means of achieving goals that are otherwise assessed as unrealistic by technocrats is noteworthy. In particular, key aspects of the Great Leap Forward included:

- Abolishment of private property and moving agricultural production into state owned communes.

- A goal of doubling steel production, in part by way of backyard furnaces.

- Massive investment in infrastructure, primarily irrigation projects.

I’ll focus on the doubling of steel production as an example of how failure to think through proper program implementation can lead to enormous waste. From Kung and Lin (EDCC, 2003):

… significant proportions of [the rural labor force] were being diverted to activities totally unrelated to agriculture, most notably the smelting of iron and mining and transporting ore in the so-called backyard furnaces. As was the case with water conservancy works, these projects similarly required that the highly fragmented and localized interests be unified. Moreover, as these were primarily industrial projects and their effective execution required managerial skills and expertise that were rarely available in the smaller collectives, the larger commune arguably provided the organizational context within which a faster pace of rural-based industrialization could be made possible.

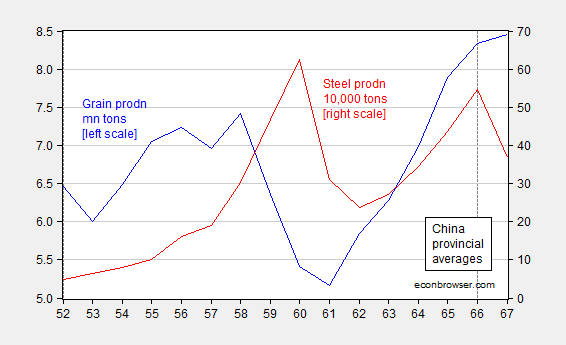

However, the economic costs of this diversion were colossal. First, the 3 million tons of steel produced in these backyard furnaces was of such poor quality that at least half of it was considered wasted. Second, unintentionally many commune authorities were so preoccupied with iron and steel manufacturing in the autumn of 1958 that they neglected to harvest the crops, which were simply left to rot in the fields. This diversion of resources is estimated to account for 28.6% of the overall grain output collapse, a factor that was secondary only in importance to excessive procurement, according to one estimate.

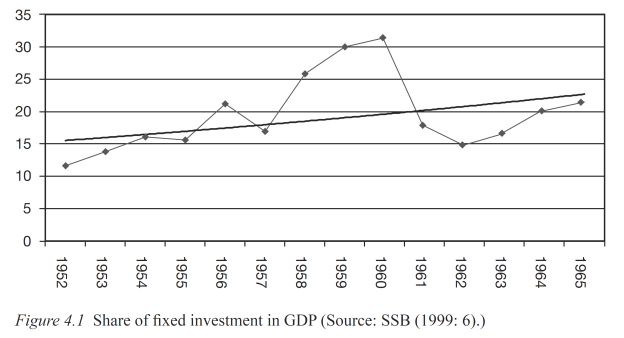

Fixed investment rose; and so initially did grain and steel production.

Source: Bramall (2009)

Figure 1: Average of provincial production of grain, in millions of tons (blue), and of steel, in 10,000 tons (red). Source: Li and Yang (JPE, 2005)

What happened in the wake of an essentially un-analyzed attempt to drastically re-orient the Chinese economy? Agricultural and industrial output collapsed. The ensuing famine resulted in 30-45 million deaths.

An ideologically driven committed “big push” involving lots of resources, unguided by careful analysis of how policies will be implemented, and likely effects, will almost certainly result in waste of monumental proportions and other unintended consequences.

More on the Great Leap Forward here and here, and Chinese development here.

Why did you choose to write about this topic?

To my mind, there’s a difference between egalitarian (communist) and conservative (authoritarian or fascist) regimes with respect to the role of technocrats.

In an egalitarian (communist) regime, the validity of the market economy as a whole is rejected. For example, when Yuri Zhivago returns to Moscow after World War I, he comes home to find the house taken over, with numerous families now claiming various parts of the building. “There was living-space for thirteen families in this one house!”, cries one of the new residents. This is not a technocratic mistake. It was not 11 or 10 families which were optimal. Rather, the communist system rejected private property outright. Thus, in Cuba, North Korea or Venezuela, the issue is not that the technocrats are sidelined. It’s rather that the entire system rejected basic principles of social organization, specifically those related to voluntary, market interactions.

On the other hand, conservative regimes are more apt to ignore technocrats. A chief example might be Hitler, who invaded Europe and opened the Eastern Front against the advice of his military technocrats–the Wehrmacht generals. For three years, however, Hitler made all the running, easily defeating France and Poland and nearly defeating the UK itself. Notwithstanding, the German generals were concerned that, were Hitler to fail in taking the oil fields in the Middle East or Caucasus, the entire enterprise would be doomed and Germany destroyed. Thus a position opened with the invasion of Poland and France could not be closed without securing an oil supply. And so it proved with the German defeats at El Alamein and Stalingrad in late 1942, after which the defeat of the Third Reich was assured.

We see many examples of conservatives ignoring technocrats at their own peril. Most recently, these might include Hungary’s Orban regime, where my own uncle was the primary technocrat ousted, at least with respect to fiscal policy. In Russia, Putin has opened a position with the invasion of Crimea without knowing how to close it. In China, President Xi appears to have eschewed policy analysis entirely with respect to policy in the South China Sea. We will see what a Trump or Sanders administration might do, but I would imagine the technocrats would have a difficult few years either way.

A final aside: Certain technocrats enjoyed a kind of immunity or autonomy in communist regimes. For example, the political officer might not want to overrule a nuclear power plant operator or a brain surgeon. Indeed, we see some of this in Dr. Zhivago, who enjoys at least some respect and independence as a medical expert.

Steve Kopits: It’s a topic of long-standing interest, which was revived by a recent presentation at La Follette by Chih Ming Tan on one of the legacies of the GLF.

Also, I think it’s a useful reminder of potential consequences, in this time of widespread disparagement of “experts”, by certain elements on both sides of the aisle. I expect it on the Republican side. I’m disappointed by those on the Democratic side who say “the details can be worked out later”. Ok when a few billion are at issue. Not so ok when trillions are.

“A ideologically driven committed “big push” involving lots of resources, unguided by careful analysis of how policies will be implemented, and likely effects, will almost certainly result in waste of monumental proportions and other unintended consequences.”

Will keep this in mind as I think about the many mandates coming out of Washington. As WJC famously said, “It all depends upon what the meaning of is is.”

Bruce Hall: You should also keep in mind when you hear that sustained 4% real growth can be achieved with current demographics and massive tax and spending cuts (JEB!nomics), or income tax cuts at current rates will results in increase in revenues (sometime-Ryanomics), or simulations incorporating yet-unobserved incredibly high labor and capital services elasticities (Ryanomics in general), and so on.

Menzie, I agree.

Most mandates are based on 1) ideological bias and 2) legal dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s. Then there is a rush to justify the mandates through social media, debating the scientific, social, and economic value of the mandates, and vilifying opponents.

It’s the American way.

I think it important to separate the objective function from its maximization. Politicians deal with the former, economists with the latter. Economists would ordinarily count as technocrats. Technocrats will find the best path to maximizing a desired objective at the lowest cost. But technocrats in general do not determine the objective function itself. Technocrats are advisers, not deciders.

For example, suppose you wanted to maximize social equality and wanted to do so as soon as possible. How would a technocrat advise you? Well, the easiest way to achieve equality is to take away the property and income of the rich (those above the mean) and prevent such disparities in wealth and income going forward. And that would give you exactly Yuri Zhivago’s homecoming to Moscow after the war. Thus, we may view post-WWI Russia with horror, but it would be a mistake to call it technocratically incompetent, at least with respect to achieving near-term equality.

By contrast, in the movie Nicolas and Alexandra, Count Witte counsels the Czar, “You could so easily stop this war, sir. All you have to do is get up, now, quietly, and go home to your family. You would be the greatest of all the Tsars.” This advice goes unheeded and, well, things didn’t turn out so well for the Czar. The Czar failed to choose the best policy for his own objective function.

I think, Bruce, you need to be careful to separate out the objective function from its optimization. As you also need to distinguish between technocratic analysis and technocratic advocacy. The former is merely intended to inform an opinion without a stake in the outcome: “Here are your options.” The latter is intended to provide support for a given ideological view, to bolster the legitimacy of a particular objective function. For example, the statement that “we will fund increased social spending by taking on debt” represents analysis. The statement “we can both increase social spending and decrease the deficit without raising taxes” is advocacy. It involves championing a particular objective function. It is politics with numbers. Krugman does a lot of advocacy on the left, as does, say, the AEI on the right.

If you separate out the objective function from its optimization–well, that’s the missing bridge between politics and economics. It would also represent a semester course right after the bit about economics being built on the assumption that wants are unlimited and resources are constrained.

The GLF / 大跃进 was indeed a tragedy. Deng Xiaoping and others helped bring technocrats back, and at least the micro history I’ve read for use in teaching suggests that the Cultural Revolution didn’t fully displace this. (I do know of specific cases of factories that remained “radical” in that teenager Red Guards were able to call the shots, to no good effect.) Rural China [or at least the rice-growing Yangtze River Delta] saw a gradual increase in diesel and then electric pumps, the construction of well-planned dikes, and over the 1970s enough fertilizer to implement Green Revolution cultivars. The latter was a product of science-based R&D, undertaken independently of similar work at IRRI in the Philippines. Rationality via formal planning, despite all its flaws, led to a tripling of yields by the breakup of the communes and the devolution of production to individual families in the post-1982 era. But I’m an economist not a historian, for whom China has been an area of teaching for 30 years, and have never read through the copious works on the GLF. Too depressing.

From informal interactions with students who grew up in China, families have kept memories of that era alive even if the era remains taboo, but it’s increasingly ancient history, fading. The Cultural Revolution remains closer to home, particularly as those who make it to the US tend to come from families where their grandparents were urban and educated, and suffered directly. I hope at some point you post reflections on that era, too.

May China and others ever remember the dangers of charismatic leaders.

I would add to your list of “here’s”

Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962 by Yang Jisheng

The book was published in Hong Kong and is now available in

English albeit half in length. The book was widely read in Hong Kong, but surprisingly banned in Red China.

Ed

Ed Hanson: “Red China”? Is Nixon still VP, and your phonograph player still working?

Fine Menzie

What do you want to call a country that tries to bury its past along with the 40 million by banning books, controlling the press and internet as well has a leadership chosen from its communist party?

We would probably call it ‘mainland China’ today, distinguishing it from Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Steven

That is a nice generic, diplomatic approach. But lets look deeper. In addition to those listed previously, the country is run by a Politburo whose members must belong to the communist party. Several industries are state owned and centrally planned. Legal internal relocation by the people is controlled by government issued paper. The military, always important to authoritarian regimes, has the power to operate under its own authority. There is still a network of informants supported by the regime, putting any who protest the restrictions of freedom summarily condemned to prison or reeducation camps. The banking system within the country is corrupt and supports the communist party higher ups (this is despite availability of a great banking industry found in Hong Kong).

To me there is nothing wrong with usage of historic names to describe what is still the case.

Ed

Ed Hanson: There once was a time when “Chinaman” was an acceptable term for describing someone of Chinese descent and/or from China. It is, I think, still an accurate description, at least in the the latter case. And yet, for some reason, for some reason, I can’t put my finger on it, it is no longer an acceptable term in polite conversation, despite it’s historical usage. Well, maybe it’s used in your “polite” conversations…

Ed –

Red China is something like the Redskins — a name without form. I think most people would apply the term ‘Red China’ to China from 1949 to the ascension of Deng to power, call it 1981, that is, when China was operating under an explicitly communist regime and ideology.

Today, the Communist Party remains ascendant, but communism as a form of government is long gone. Rather, we see a kind of authoritarian economic liberalism. Indeed, I have harshly criticized President Xi for trying to take China back in a totalitarian and, to appearances, Marxist direction. (This risk appears to be fading in the last month or so.) At the same time, China has three times as many women billionaires as does the US. That’s hardly communist.

Thus, the term ‘red’, to mean the ascendancy of the Communist Party in a non-democratic regime is correct. However, using ‘red’ to imply that China is operating under a communist ideology a la 1967 is plainly wrong. For that reason, I think the common parlance today is ‘mainland’, not ‘red’. No one debates the points you make, but China today is closer to Singapore than it is to, say, Cuba.

steven, the use of the phrase “red china” is simply a dog whistle for a certain group of political think. there is a group of people in the us that are very susceptible to the effects of the dog whistle, and it is used over and over to great effect. the use of the term is not meant to be descriptive, it is meant to bring out a particular response from those susceptible to it.

I am not debating the substance of Ed’s comment, merely the descriptor he uses.

At the same time, I would note that the Chinese Communist Party has lifted more people, more quickly out of poverty than any other government ever anywhere.

To me, China is a glass half full, not half empty.

Today’s issues revolve around how to keep the momentum going. To my mind, this requires substantial liberalization, bureaucratic modernization, and process restructuring. Purges are not going to do the trick.

The questions Xi needs to be asking with respect to the bureaucracy are:

– Is this (whatever it is) something that the government should be doing at all? Does it conform to everyday notions of legality and morality?

– Can we restructure a process (say, building permits) to i) speed up the process, ii) better align the process with desired outcomes (ie, insuring building permits and inspections actually deliver safe buildings), iii) reduce the opportunity for corruption (eg, online applications and remote processing), and iv) change compensation to reduce the incentive for corruption?

So, I would like to see more stories about McKinsey and Deloitte and IBM restructuring the Chinese bureaucracy. And I’d like to see a lot less about lower level purges. In other words, I would like to see technocrats have a greater role.

As for ‘Chinaman’, Menzie, we don’t use ‘Englishman’ anymore either. I suspect it has to do with the greater visibility of women, prompting the removal of ‘man’ from the description. Ergo, Englishman becomes English, and Chinaman becomes Chinese.

Damned women. In no time, they’ll want their pictures on our currency.

Steven Kopits: As late as 1991 or so, The Economist was using the term “Chinaman”, as if it was quite normal. They stopped using it after I wrote a letter to the editor (may be coincidental, or maybe not).

The PRC is not a free country, the ruling party is afraid of its own people and is monitoring them closely (and not only because of these ‘Panama connections’ by the party elite).

The terminus ‘Red China’ is still in use today, as for example in the NYT, and not derogatory.

After all, ‘Red’ is the color of the ruling party.

If the USA is a free country, we can discuss.

“The terminus ‘Red China’ is still in use today”

it is still a dog whistle.

Baffs is correct on this. I cannot find the use of “Red China” outside far right websites. It returns nothing on the WSJ.

China is a mixed free/not free country. It’s not like, say, Hungary under Communism, where the news was really not news at all. Rather, you can read the news in China, but certain sensitive issues are taken out, either by self or government censorship. You couldn’t read Econbrowser when I was last there.

The issue now is whether this is going to get worse. Apple’s iTunes store was shut down today in China.

And by the way, if you want a party afraid of the people, I give you the Republicans. Read Peggy Noonan’s op-ed today. I am as worried as she is.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/that-moment-when-2016-hits-you-1461281849

noonan is a part of the problem. if she wants to help, she should go silent and slip into the darkness. a professional pundit needs to create controversy to stay relevant, and she has done that through the years. but by doing so, she was a contributor and enabler to the current classless group of politicians she is responsible for creating. she is subtle, but nevertheless a contributor. she makes the statement “Alongside that, the enduring power of a candidate even her most ardent supporters accept as corrupt.” Now, her article is about the classlessness of the republican party and its current crop of candidates, but she cannot help to take a dig at the other side. not classy behavior for a journalist, or somebody who wants to be taken seriously.

If you really believe that the problem with the Great Leap Forward was insufficient technocratic planning, you seem to have missed the outcome or importance of the socialist calculation debate. The Great Leap Forward is an outlier in the results of technocratic planning only in size, not kind.

I think this is correct. The essence of a communist regime is the elimination of price signals in allocating resources. In their absence, something like the Great Leap Forward becomes possible.

Still, I think that Menzie’s point is correct. Even within a communist ideology, the Great Leap Forward was a bad idea.

Some pretty good news out of China today. Xi is looking for a PR firm.

Reuters reports that “five global public relations firms have made pitches to the Chinese government for a potential new campaign, four sources said, as Beijing tries to communicate more effectively with the West.” The reason? Chinese leadership thinks they are “”being unfairly treated by foreign media.”

Having done my share of consulting to post-socialist governments, I can say how I think this dialogue will go (at least after the contract is signed). The government is going to ask to have certain types of news stories suppressed or recast in a better light. And the agency–these are all international ad agencies–will respond that they cannot compete with the news cycle, for example, this gem, which was front and center on the Drudge Report yesterday. They will state that the agency can put a good face on and explain a given policy or government action, but they cannot make a bad action look good. Ogilvy Public Relations can’t make aggression in the South China Sea look benign.

This in turn will create push-back on the government, hopefully resulting in some restraint. And this in fact what we have seen in the last five weeks or so.

So, right now, China is headed in a better direction.

The above mentioned ‘gem’: http://www.mirror.co.uk/tech/china-tests-terrifyingly-powerful-dongfeng-7803132