Today we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Alessandro Rebucci, Associate Professor, and Jiatao Liu, at the Carey School of Business at Johns Hopkins University.

This month marked the beginning of the 10th year since the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which triggered the most acute phase of the U.S. subprime financial crisis. The United States is still coping with the consequences of the ensuing great recession, and its policymakers have spent the past decades reining-in an overgrown financial system. Over the past 10 years, in contrast, China’s policy makers have worked toward getting the domestic financial system off the ground and connecting it with global capital markets. This is an opportune time to take stock of what lessons can be drawn for China from the American experience.

- Mind the regulatory “perimeter.” In the U.S., a too-narrowly defined regulatory perimeter around traditional banks gave pervasive incentives to shift activity and risks outside it in the so-called shadow banking system. Until recently, regulation of the banking system in China was repressive and it continues to be much stricter than in the United States. As a result, over the past 10 years, shadow banking has exploded in China to circumvent strict credit and interest rates controls. An innovative, efficient financial system has now developed. But risks and vulnerabilities have grown dramatically alongside with it. The latest of these is a huge bubble in crypto currencies to avoid restrictions on capital outflows.

- Watch for “excesses” in the real estate sector. Real estate is the largest asset class in households’ portfolios, an important market segment for financial businesses, and a key source of revenue for local administrations in the United States, as in China. Once imbalances build, they unwind very slowly, affecting the economy for a very long time. Real estate crises affect banks and take much longer to resolve than a crisis in the stock or FX market, like the ones experienced by China in 2015. In China, real estate boomed during the past 10 years, fueled by an extremely fast urbanization and rapid income growth, but also by abundant credit, lack of diversification opportunities, and restrictions in the budgeting process of provinces and cities.

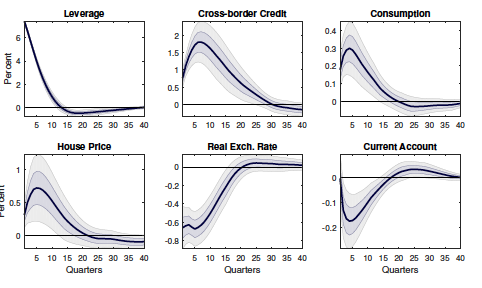

Figure 1. Leverage shock. Note: 1 Percent increase in the leverage. Real exchange rate, an increase is a depreciation. - Keep the financial system simple. Complexity is difficult to evaluate and distorts financial decisions. While the regulator may have a good sense of the total quantity of systemic risk, monitoring its distribution and concentration is nearly impossible. Complexity also impedes efficient intermediation and liquidity provision. For instance, while there are potentially enormous benefits from the emergence of a thriving fin-tech industry, fin-tech increases add to complexity by posing operational and technology risks of different orders of magnitude.

- Financial crises are costly, and these costs are not spread evenly. Crises disproportionally harm the young and the old. Younger workers are the first to be laid off and, because of their lack of experience, find it hard to regain employment. An entire cohort of high school, college, and MBA graduates saw a sharp deterioration in their lifetime earnings over the past several years in the U.S.. Older workers in those same households saw not only their lifetime savings but also their prospects of reemployment vanishing with the crisis. Financial crises increase income inequality and hurt the poor disproportionately because they have worse access to social protection, medical insurance, and access to credit. Ultimately, financial crises cost the jobs of the politicians at the helm of society. The new waves of protectionism and populism in the U.S. and Europe owe much more to the global financial crisis than to the merits of those economic and political ideas.

- A government-run financial system is not immune from trouble. Using public financial enterprises to cushion the blow, such as the U.S.-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, shield the national budget from the credit rating agencies but it is short-sighted. Using GSEs to keep the financial system afloat, like regulatory forbearance, saved costly capital and scarce liquidity resources during the crisis, but undermined their long-term financial independence and hence their support role for the efficient allocation of credit risk in the US system. One bequest of the U.S. crisis has been the politically intractable issue of GSE reform: once scaled up to resolve the crisis, scaling down this type of government intervention does not take years, but decades, and is a politically charged enterprise.

- Macro-prudential policy is not a silver bullet. In the presence of financial excesses, monetary policy might have to be tighter than what it would be, based only on business cycle conditions. In theory, macro-prudential policy could target financial excess, and monetary policy the business cycle, but it is hard to find effective tools and even harder to know how to adjust them over the cycle. In the United States, regulatory tools to moderate the financial cycle in the run-up to the crisis were available, but were perceived to be ineffective. The short-term interest rate was the only instrument that could have gotten get into all cracks of the financial system and provide incentives to internalize risks and externalities. In the run-up to the crisis, some feared introducing distortions in the broader economic system by using monetary policy to address the problems of a specific sector. It is now well understood that monetary policy has to trade off economic and financial stabilization gains in the presence of distortions in financial intermediation.

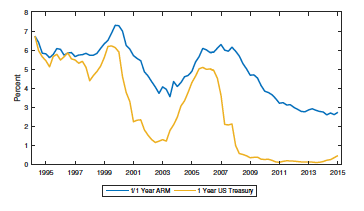

Figure 2. US Mortgage and Treasury Rates. - Read carefully your brokerage statement, your mortgage contract and your lease. Financial literacy and consumer protection are as important as financial innovation and development for efficient and safe intermediation. At the core of the U.S. crisis were also outright fraud and the financial illiteracy on which fraud thrives. A domestic financial system that is dynamic and innovative supports and facilitate consumers’ risk sharing and firms’ investments. But efficiency also requires information and the ability to process it. Promoting financial literacy and protecting consumers from fraud and predatory lending is all the more important in a fast- growing system such as China’s.

- When the intermediaries are big, they are too big to fail. We don’t know what the optimal size of banks and financial intermediaries is. Financial intermediation needs economies of scale to reduce costs and operate efficiently. But excessively large financial institutions are hard to liquidate in the case of insolvency, like Lehman Brothers, AIG, and other entities that had be resolved during the U.S. crisis. They also create pervasive moral hazard problems in the system. This challenge is compounded by concern for monopolistic behavior in China’s mushrooming fin-tech industry. While still a relatively small-scale industries in the U.S., crowd sourcing, P2P lending, mobile payment systems, and crypto currencies have already grown into big businesses in China with high concentration and astonishing penetrations shares among households and firms.

- If a crisis struck, it would need to be resolved as quickly as possible. The speed, size, and momentum of the policy intervention matters for the final outcome. Crisis resolution interventions must be fast, larger than strictly necessary to resolve the problem, and sustained past the immediate urgency. While the U.S. monetary policy response to the subprime crisis was very different from the Federal Reserve’s response to the Great Depression of the 1930s, the fiscal policy response got stuck in the legislative process. The result has been an anemic recovery and lingering fears of relapse, which lasted well after the recession was officially over. In contrast, China’s intervention in the equity and foreign exchange market in 2015, while heterodox and hence problematic in a nascent financial system, was massive and decisive, which explains why it succeeded despite its shortcomings.

- No crisis is alike. The next financial crisis in the United States will be different from the previous one. Policy makers sometime sow the seeds for the next financial crisis by how they respond to the previous one. In the United States, aggressive financial deregulation aimed at creating a level playing field for banks combined with low inflation and very successful monetary policy ultimately led to the subprime excess and collapse after the Saving & Loan crisis. The next financial crisis in China will be different from the one in the United States. Nonetheless, financial crises have a centuries-old history and will continue to happen. A financial system that is crisis-proof would be an excessively stiff and cannot support growth and innovation. Fortunately, China has the privilege to be able to design its own with the benefit of the lessons learnt from other countries and eras, including the 10-year old crisis in the United States.

This post written by Alessandro Rebucci and Jiatao Liu.

Also, it’s not a good idea to provide home loans to people who can’t afford them or bigger loans than they can afford to raise the homeownership rate and provide bigger houses for social and economic reasons, because in an economic downturn, it can bring down the entire housing market.

And, after the housing market crashes, it’s not a good idea to go from one extreme to the other with excessive regulations making it harder to get a home loan (i.e. closing the barn door after the livestock escaped), along with imposing other anti-growth policies to slow the recovery.

China has a ridiculously inefficient government. It spends to build ghost cities with no return on investment, although it does creates jobs (perhaps, better than doing nothing and collecting welfare). Nonetheless, people suffer under the communist system. For example:

“In 2010, the governments of Shanghai and Beijing invested nearly $60 billion to bring the World Expo to Shanghai. They kicked people off their land. All told, 18,452 households got eviction notices. Some 270 factories had to move. China’s “stroke-of-a-pen” economy can change fortunes just like that. Those who complained about the relocation program were arrested in typical Chinese fashion. The focus of the Expo was “Better City, Better Life”, but ironically, what it left behind was a ghost town. When it was over, Shanghai was left with a swathe of land the size of Monaco with absolutely nothing going on. Many of the buildings were demolished.”

“China has a ridiculously inefficient government.”

by what metric? i am not here to defend the chinese system. However, the growth of china has been extraordinary over the past several decades. the ghost cities are filling up over time, but they are also required in a sense of the rapid urbanization of the country. people will not urbanize without completed infrastructure to move into. their scientific and technological advances are impressive, and continue to grow in an organic setting at this time. you may not like their methods in china, but i am not sure the term “ridiculously inefficient” is an appropriate description.

Basically, the China model is a totalitarian state exploiting the masses and the environment.

The communist elites give the masses enough to keep them working and prevent a rebellion.

Sorry, China, There Is No Short Cut To Economic Greatness

Jan. 26, 2010

“This is a government that will go to great length to maintain appearances to keep its ideology going. After all, it censors what its citizens may or may not read and imprisons the ones that write anti-government articles.

China will do anything to grow its economy, as the alternatives will lead to political unrest…Since China lacks the social safety net of the developed world, unemployed people are not just inconvenienced by the loss of their jobs, they starve (this explains the high savings rate in China) and hungry people don’t complain, they riot.

The Chinese government controls the banks, thus it can make them lend, and it can force state-owned enterprises (a third of the economy) to borrow and to spend. Also, since the rule of law and human and property rights are nascent in its economic and political system, China can spend infrastructure project money very fast – if a school is in the way of a road the government wants to build, it becomes a casualty for the greater good.

China has spent a tremendous amount of money on infrastructure over last decade and there are definitely long-term benefits to having better highways, fast railroads, more hospitals, etc. But government is horrible at allocating large amounts of capital, especially at the speed it was done in China. Political decisions (driven by the goal of full employment) are often uneconomical, and corruption and cronyism result in projects that destroy value.

The inefficiencies are also evident in industrial overcapacity. According to Pivot Capital, Chinese excess capacity in cement is greater than the combined consumption by the US, Japan, and India combined. Also, Chinese idle production of steel is greater than the production capacity of Japan and South Korea combined. Similarly disturbing statistics are true for many other industrial commodities.”

I stated before, what the communist Chinese do best is corruption, crony capitalism, misallocate resources, cause negative externalities, prevent creativity, create inefficiency, and export much of its GDP. Moreover, it steals a lot of intellectual property (a communist government doesn’t care much about property rights anyway).

Myth of China’s Manufacturing Prowess

March 10, 2010

“People often compare China’s urbanization to Western industrialization in the 19th century. In both cases, a large population moved from the country to the city. Society advanced from agricultural to industrial via manufacturing on a massive scale.

In the United States and Europe, the manufacturing industry was created due to technology innovation. For example, railways came into existence because of the invention of the steam engine, and automobiles were created because of technology breakthroughs in automobile engines.

In China, the manufacturing industry is being created in response to global demand. Chinese manufacturers take orders from Western companies that have designed products for their home markets. They have no involvement with product development, innovation, market research, and even packaging.

James Fallows (an economist) visited many factories in China. He saw people working on the assembly lines and was convinced those tasks would only be performed by machines in the United States.

In 2008, U.S. manufacturing output was $1.8 trillion, compared to $1.4 trillion in China….the United States is producing goods with higher value, such as airplanes and medical equipment.

In addition, most jobs the United States lost to China are low-skilled jobs. By outsourcing those low-skilled jobs to China, Americans have actually become more competitive in high-skilled jobs such as management, innovation, and marketing.”

PeakTrader James Fallows (an economist) visited many factories in China.

James Fallows is an interesting guy, but for the record he is not an economist. His Wikipedia entry tells us that he has a BA in history and literature. He “studied” economics at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, but that does not mean he is an economist in the ordinary use of the term.

your references are nearly 8 years old! China has changed immensely in the past decade. in addition, those commentary do not support your statement with any strong evidence:

“China has a ridiculously inefficient government.”

you do not like the government of china and its methods. understood. but your argument is not supported by any evidence. china has grown between 6% and 10% a year for the past decade. nothing inefficient about this whatsoever.

“I stated before, what the communist Chinese do best is corruption, crony capitalism, misallocate resources, cause negative externalities, prevent creativity, create inefficiency, and export much of its GDP.” Lets be clear. this is your OPINION, and not really supported by facts. you seem to be attacking china based on ideology rather than reality. china does have issues which need addressing, but you are not framing your arguments in reality peak.

No amount of proof will change your ridiculous beliefs and rigid ideology baffling

I stated before and shown evidence when negative externalities are taken into account, e.g. environmental and safety, GDP growth would be reduced up to 3%. Opportunity costs, e.g. maintaining a safety net rather than spending on unneeded projects, overstate GDP growth. Without net exports, GDP growth would be much lower. China’s consumption was falling and remains low as a percent of GDP. Moreover, government suppresses or supplants much of the free market to prevent GDP growth. Living standards are improving much slower than reflected in GDP growth.

“No amount of proof will change your ridiculous beliefs and rigid ideology baffling”

peak, why the insult? i stated neither “beliefs” or “rigid ideology”. i simply commented that your sources are nearly a decade old and do not reflect the current state of china. why do you continue to be upset when somebody points out the flawed data upon which you make your case?

my guess is you have never been to china. but you seem to be confident you understand its workings. you would appear to be rather uneducated on the culture and economy of china outside of what you learn in the faux echo chamber. china has problems to be solved, for sure. but i am not sure your “solutions” are applicable to modern day china.

Certainly a very interesting list of lessons but I was taken aback by #6

“It is now well understood that monetary policy has to trade off economic and financial stabilization gains in the presence of distortions in financial intermediation.”

Is it? There are important reasons why using the interest rate to try and reduce the build-up of debt would be counterproductive. Raising the interest rate doesn’t just have a cost in terms of higher unemployment and lower growth in good times, it also means the country will begin with more unemployment if a crisis does occur. The crisis will therefore lead to higher unemployment and output further below optimum than it would have without the interest raise.

Raising the interest rate also reduces inflation, increasing the real value of the stock of debt held by households. This is a problem since the flow of additional debt is usually far smaller than the stock of existing debt. In short, higher interest rates may reduce the rate of debt accumulation but they also increase the real value of existing debt and the end result on financial stability is unclear (it could go either way). The cost of raising interest rates prematurely are very clear however.

I realize there are solid economists on both sides of this debate (some would argue that higher interest rates can help) but since there is no consensus I’m surprised it made it onto the list.

That’s what the last sentence says, but the first sentence says: “In the presence of financial excesses, monetary policy might have to be tighter than what it would be, based only on business cycle conditions.” So, the last sentence makes sense in that context.

Financial excesses was a major influence on the economic expansion. Regulation was a more appropriate tool for financial excesses than monetary policy, which eventually became restrictive causing the recession initially, in December 2007. The housing boom fueled the expansion. Financial regulation and tax cuts instead would’ve averted the financial crisis and severe recession.

Yes there are good arguments on both side of the debate. The point above was that, as long as we dont find the “silver bullet” of macro-pru (i.e., effective tools, and knowledge on how adjust them over the cycle), we cant risk another debacle like in the run up to the GFC.

The list reflects much acute analysis

However

The long ugly shadow

Cast by American orthodox academic models

Poisons too many of the proffered buffet dishes

China needs better state imposed mechanisms

Like a mark up cap and trade system or better

A system of cap and trade systems

More comprehensive dynamic and smart

tax and subsidy systems

A new model for a central organizing and mobilizing node

I.e. Beyond the older generation of central ” plans ”

Automatic smart regulatory systems

Btw

Fin tech is largely incentivized by holes and pokey rates of adjustment in existing financial markets

The shock and awe cult

Behind the profane word “risk ”

is big Satan worship

Risk management is about known distributions

Uncertainty must be managed

Including the secondary uncertainty

created by the existing institutional arrangement itself

Will any of this make sense to readers ?

I doubt it

But beware the capitalist corporate restoration

lurking like lifting fiends

behind these brigh authors

Largely well founded and important suggestions and caveats

The implied solutions lean toward corporate bedlam

Single call to the politburo

Comprehensive George tax

Implemented in stages

Starting now !