Nominal GDP targeting has been advocated in a recent Joint Economic Committee report “Stable Monetary Policy to Connect More Americans to Work”.

The best anchor for monetary policy decisions is nominal income or nominal spending—the amount of money people receive or pay out, which more or less equal out economy-wide. Under an ideal monetary regime, spending should not be too scarce (characterized by low investment and employment), but nor should it be too plentiful (characterized by high and increasing inflation). While this balance may be easier to imagine than to achieve, this report argues that stabilizing general expectations about the level of nominal income or nominal spending in the economy best allows the private sector to value individual goods and services in the context of that anchored expectation, and build long-term contracts with a reasonable degree of certainty. This target could also be understood as steady growth in the money supply, adjusted for the private sector’s ability to circulate that money supply faster or slower.

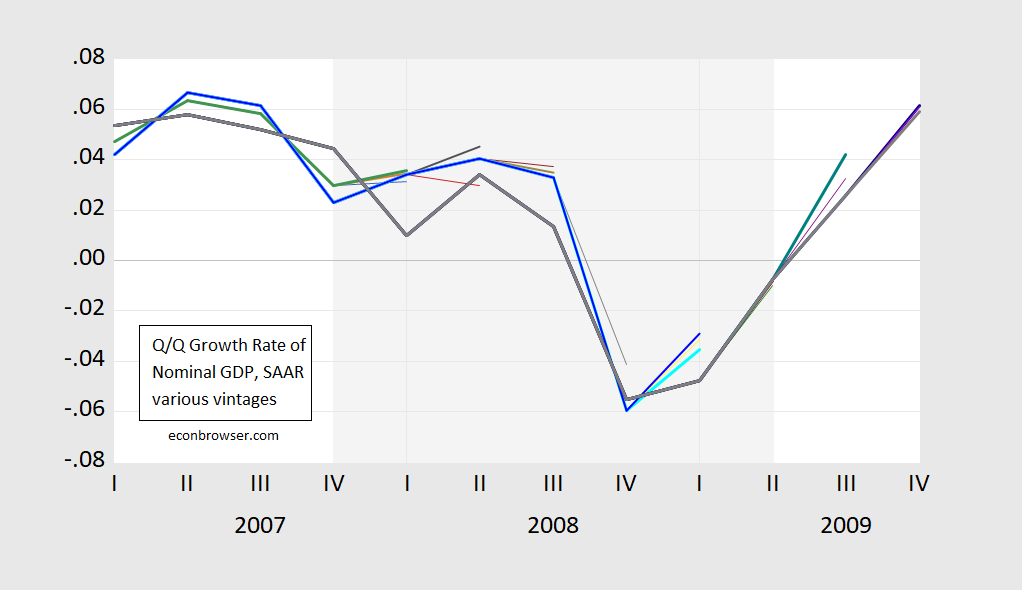

One challenge to implementation is the relatively large revisions in the growth rate of this variable (and don’t get me started on the level). Here’s an example from our last recession.

Figure 1: Q/Q nominal GDP growth, SAAR, from various vintages. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: ALFRED.

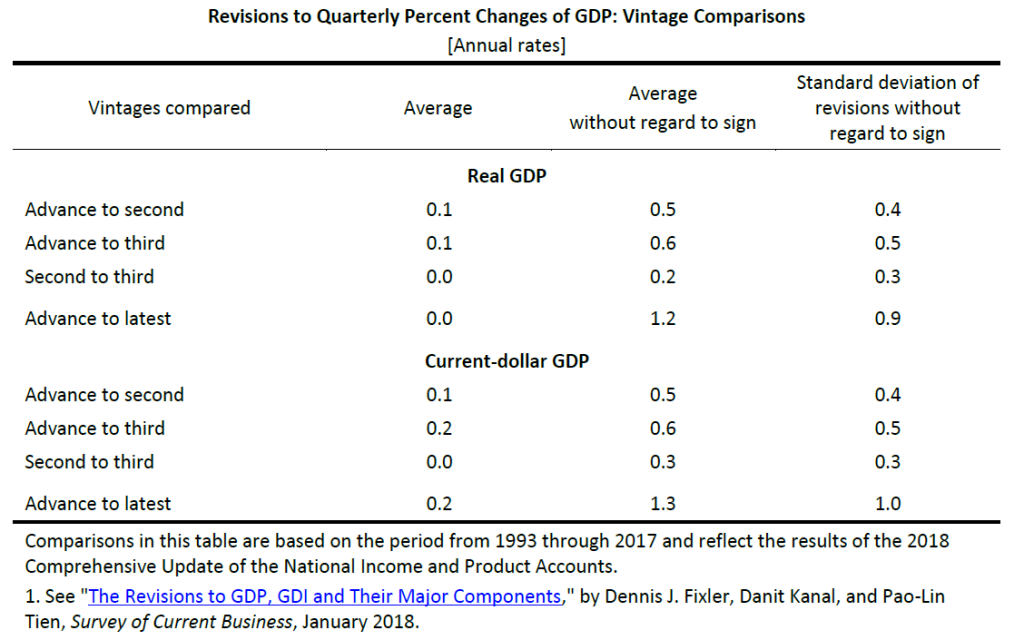

How big are the revisions? The BEA provides a detailed description. This table summarizes the results.

The standard deviation of revisions going from Advance to Latest is one percent (annualized), mean absolute revision is 1.3 percent. Now, the Latest Vintage might not be entirely relevant for policy, so lets look at Advance to Third revision standard deviation of 0.5 percent (0.6 percent mean absolute). That’s through 2017. From the advance to 2nd release, 2020Q2 GDP growth went from -42.1% to -40.5% (log terms).

Compare against the personal consumption expenditure deflator, at the monthly — not quarterly — frequency; the mean absolute revision is 0.5 percent going from Advance to Third. The corresponding figure for Core PCE is 0.35 percent. Perhaps this is why the Fed focused more on price/inflation targets, i.e.:

…variants of so-called makeup strategies, “so called” because they at times require the Committee to deliberately target rates of inflation that deviate from 2 percent on one side so as to make up for times that inflation deviated from 2 percent on the other side. Price-level targeting (PLT) is a useful benchmark among makeup policies but also represents a more significant and perhaps undesirable departure from the flexible inflation-targeting framework compared with other alternatives. “Nearer neighbors” to flexible inflation targeting are more flexible variants of PLT, which include temporary PLT—that is, use of PLT only around ELB episodes to offset persistently low inflation—and average inflation targeting (AIT), including one-sided AIT, which only restores inflation to a 2 percent average when it has been below 2 percent, and AIT that limits the degree of reversal for overshooting and undershooting the inflation target.10

Admittedly, the estimation of output gap is fraught with much larger (in my opinion) measurement challenges than the trend in nominal GDP, as it compounds the problems of real GDP measurement and potential GDP estimation; this is a point made by Beckworth and Hendrickson (JMCB, 2019). Even use of the unemployment rate, which can be substituted for the output gap in the Taylor principle by way of Okun’s Law, encounters a problem. As Aruoba (2008) notes, the unemployment rate is not subject to large and/or biased revisions; however the estimated natural rate of unemployment, on the other hand, does change over time, as estimated by CBO by Fed, and others, so there is going to be revision to the implied unemployment gap (this point occupies a substantial portion of JEC report). Partly for this reason, the recently announced modification of the Fed’s policy framework stresses shortfalls rather than deviations, discussed in this post.

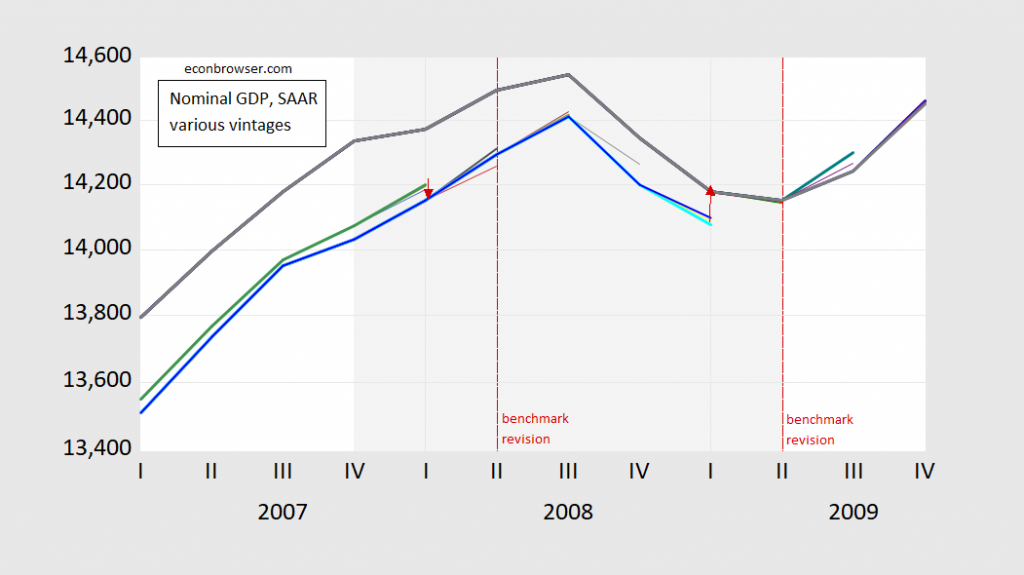

One interesting aspect of the debate over nominal GDP targeting relates to growth rates vs. levels. If it’s growth rates (as in Beckworth and Hendrickson (JMCB, 2019), there is generally a “fire and forget” approach to setting rates. An actual nominal GDP target of the level implies that past errors are not forgotten (McCallum, 2001) (this is not a distinction specific to GDP as we know from the inflation vs. price level debate). Targeting the level of nominal GDP faces another — perhaps even more problematic — challenge, as suggested by Figure 2.

Figure 2: Nominal GDP in billions of current dollars, SAAR, from various vintages. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed red line at annual benchmark revisions. Red arrows denote implied revisions to last overlapping observation between two benchmarked series. Source: ALFRED.

Revisions can be large at benchmark revisions, shown as dashed lines in the above Figure. But even nonbenchmark revision can be large, as in 2009Q3. ( Beckworth (2019) suggests using a Survey of Professional Forecasters forecast relative to target and a level gap as means of addressing this issue — I think — insofar as the target can be moved relative to current vintage.)

None of the foregoing should be construed as a comprehensive case against some form of nominal GDP targeting — after all Frankel with Chinn (JMCB, 1995) provides some arguments in favor. But it suggests that the issue of data revisions in the conduct of monetary policy is not inconsequential.

I have made the point in the comments to Scott Sumner’s blog about the importance of specifying an NGDP rule so that the impact of revisions is reduced. The simplest adjustment is to specify the rule in terms of the NGDP in the future divided by the NGDP at some in the past, rather than in terms of the levels themselves. This means that the only impact of the revisions is over the lookback period, rather than the whole history of NGDP.

Also, it looks from your table that revisions for NGDP are very similar to those for RGDP. That means that any monetary policy rule that uses RGDP should have the same concern.

A lot of this flies above my head, and I still need to digest large portions and hopefully get around to reading the papers. But I will say this, I find, and have found for a long time, going back to my college years and possibly before that, the idea of a “natural rate of unemployment” to be offensive in a personal way, and also on moral grounds. I believe it’s a rationalization to shrug your shoulders at those on the outskirts of society. And although I do not have a degree in Economics, I’ve done a fair share of reading in my day on the topic, and I would also say much greater minds than mine share my anger on this phrase “natural rate of unemployment”. I find it unacceptable, not “natural”, and worms will be eating away at my dead tissue somewhere, before I change my stance on this topic.

If that makes me “narrow minded” or “closed minded” then here I am, the “narrow minded guy”.

When I learned it, the idea of a natural rate of unemployment is to allow people to voluntarily change jobs. If unemployment is strictly zero, there are no open jobs to move to. So the natural rate is from people moving from job to job, and their current position coming open when they move. Of course, during my working life I’ve also seen a lot of people leave a job without a new one already lined up, thereby creating an opening for someone else to move into.

When I learned it there were three types of unemployment. The first kind (i.e., the good kind) is frictional unemployment in which people are literally in-between jobs. I quit my job last week because I’m starting my new and higher paying job next week. The second kind of unemployment is structural. Structural unemployment would include legal impediments such as an excessively high minimum wage, excessive licensing requirements, systemic racism, etc. The third kind of unemployment is cyclical and goes up and down with the business cycle. In an ideal world we would like to see a high frictional unemployment and low structural & cyclical unemployment.

Actually, 2slugs, there are four kinds. Structural is usually defined as being “a mismatch of skills available and skills needed,” which can arise from sectors rising and declining with a lag in labor training. It is usually viewed as including such things as discrimination. The fourth kind is “classical” wages being “artificially” held above their equilibrium level, which might be due to overly high min wages or meanie greedy unions.

I’ve always wondered why GDP is the primary measure of economic health. I would have thought that something like median disposable income (after taxes, food, clothing and shelter) would be a better measure of economic health. “How much money does a typical person have after paying for survival?” Yet I can’t find data to derive this.

Gord Gray I always wondered why we didn’t put more emphasis on Net Domestic Product. NDP tells us how much we can consume without eating into our seed corn.

The JEC’s timing brings an element of – comedy maybe? – to the policy sphere. The FOMC has been considering various operational approaches to increase policy effectiveness in a low-rate environment for over two years. Yesterday, the Committee announced its choice, and it was not NGDP targeting. The JEC report was released just two days before the Fed announcment, so almost certainly after the Fed’s decision had already been made. Nicely done.