Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution written by Yin-Wong Cheung, Professor of International Economics at City University Hong Kong, formerly professor at UCSC, and Risto Herrala, economist at the Bank of Finland.

The recent years have been a frustration for anyone trying to make sense of China’s capital control policies. Capital controls have been an important part the Chinese economic policies since the communist revolution in 1949 but, after the reform and opening policies were initiated in the late 1970’s and China’s march back towards a market economy began, they appear more and more an anomaly. At present, the dominant view both among Chinese policy makers and analysts is that at some point the restrictions have to go. They are incompatible with the pursuit of a free market economy especially for a country with a leadership role in international commerce.

However, as with many other reforms, the chosen model of capital account liberalization has been baby steps. So far, the on-going millennium has been characterized by a long chain of small capital account liberalization measures, all of which have at least seemingly opened up some new channel for Chinese firms to transfer funds abroad or foreigners to invest in China. An important related development has been the emergence of Hong Kong as the hub of RMB trade abroad, where off-shore RMB can be deposited and freely traded. So, after all these developments, are the controls still effective? And if so, to what end?

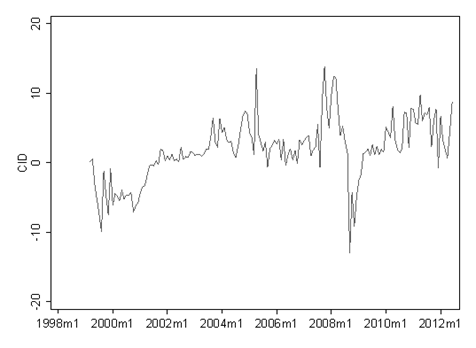

To shed light on these issues, we study the covered interest differential (CID) between onshore and offshore RMB (the paper, working paper version). The CID is a much used measure of the effectiveness of capital account restrictions because it vanishes by arbitrage under free capital mobility. So, if we find that the CID is still large (in absolute value), we can be confident that capital account restrictions are binding, and the arbitrageurs have not yet had their day.

Figure 1: Covered interest differential (CID) between onshore and offshore RMB

This is, indeed, what we find. According CID graph, if anything, the CID seems to be getting larger, since it shows an increasing trend after the most likely regime shifts in the series are controlled for. The regime shifts mark milestones in Chinese monetary policy: around July 2005, China effectively shifted from a heavily managed fixed exchange rate policy towards the USD to a crawling peg, and around June 2008, in the midst of the global financial crisis, China re-instated its pre–2005 heavily managed exchange rate policy.

While the ‘whether’ question is therefore settled in the affirmative, the ‘why’ question is less straightforward to answer. We approach this issue by first testing the power of the usual explanatory variables which proxy the intensity of capital account restrictions, country risk, exchange rates and trade. Of such variables, the CID reacts significantly only to changes in exchange rates: it is increasing in exchange rate volatility, and decreasing in the nominal effective exchange rate. These findings suggest that the CID is more closely linked to financial rather than real developments.

An alternative view on the issue has, however, recently been proposed by Jeanne (2012), who shows that capital account restrictions gives effects similar to those of trade protectionism measures. Capital account restrictions could be used to undervalue a currency by restricting capital flows inwards thereby contributing to an increase in competitiveness of Chinese firms. Interestingly, such a scheme has implications regarding the CID which we can test. The tell-tale signs of such policies are, a positive CID (which we find), an undervalued currency, and tightness of credit conditions within China. The theory therefore provides an explanation of our finding of a significant negative link between CID and the nominal effective exchange rate. By including alternative credit market tightness indicators as explanatory variables of the CID, we are also able to confirm the theoretical prediction of a significant positive link between the CID and credit market tightness within China.

Apparently, China still considers capital control policy to be an indispensable tool to manage and stabilize the economy. However, the estimation results support the criticisms that use of capital controls to restrict capital inflows and thereby undervalue the RMB comes at high cost. It is at variance with the goal to develop the domestic economy, since it depresses credit availability within China. The question is therefore not whether to reform; the relevant questions are on the speed and the extent of the reform program under the new government.

References

Olivier Jeanne, “Capital Flow Management,” American Economic Review 102(3): 203-206.

This post written by Yin-Wong Cheung and Risto Herrala

Off topic, but very important not only in case you have Bitcoins :

Hi to everyone, esp. J. Hamilton,

a few weeks ago, JDH posted about Bitcoins. Here is the link to the crisis strategy draft about the Mt. Gox insolvency.

Call the draft source verified.

http://de.scribd.com/doc/209050732/MtGox-Situation-Crisis-Strategy-Draft

Note : they intend to inject 200000 bitcoins during restart. And take your conclusions from that.

Regards

Oh, yeah. This is a great topic. Wish I had more time to delve into it, but this is a really interesting story, I think. Great post.

“Jeanne (2012), who shows that capital account restrictions gives effects similar to those of trade protectionism measures. Capital account restrictions could be used to undervalue a currency by restricting capital flows inwards thereby contributing to an increase in competitiveness of Chinese firms.”

This is all painfully obvious and has been for a number of years. The purpose of the strategy is to get more AD in a world of deficient AD. Without the capital controls, China’s currency manipulation (which has caused China to amass $trillions in foreign exchange reserves) would largely be undone by private capital flows. (We needed Jeanne to **show** this?) Currency manipulation is the ultimate in trade protectionism, simultaneously limiting imports and encouraging exports. It is much more effective than tariffs or quotas at enhancing the current account balance,

“A fascinating presentation by Steven Kopits, Managing Director, Douglas-Westwood, for the The Center on Global Energy Policy, recorded February 11, 2014. Kopits examines oil supply and demand modelling, peak oil, the link between oil and the economy, and capex spending in the oil industry.”

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2014-02-25/oil-supply-and-demand-forecasting-with-steven-kopits

This is an excellent post! It is a good metric to judge the impact of the actions the Chinese government is taking. The real question is whether there is sufficient increase from trade protectionism to offset the destruction caused by domestic currency manipulation. Since such increases in trade are negligible this kind of manipulation probably hinders overall economic growth.

The political fear of the Chinese government is restricting their growth.