An argument increasingly being made is that inflation is being built into wage demands in a context of really tight labor markets, and this would induce a wage-price spiral. This outcome is plausible, but I think it’s useful to compare wages against CPI to see if wages are really abnormally high, and are starting to rise in tandem with inflation. [text corrected 8/13]

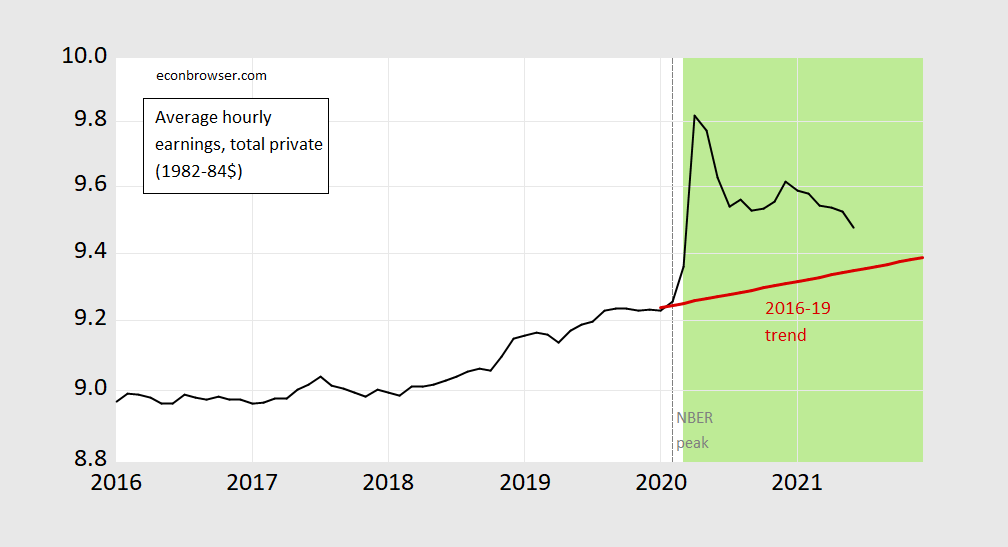

If one examines average hourly earnings in the private economy, not holding composition constant (and in excluding supervisory and nonproduction workers), then in fact the real wage looks high, but is declining through June. [text corrected 8/13]

Figure 1: Average hourly earnings for total private industry ex-nonproduction and supervisory workers, deflated by CPI-all (black), and 2016-19 stochastic trend (red), both in 1982-84$. Source: BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

However, once one looks more Looking at front line workers — i.e. excluding nonproduction and supervisory workers, and controls slightly for sectoral composition, one finds a more complicated story. Consider at the extremes manufacturing and accommodation and food services.

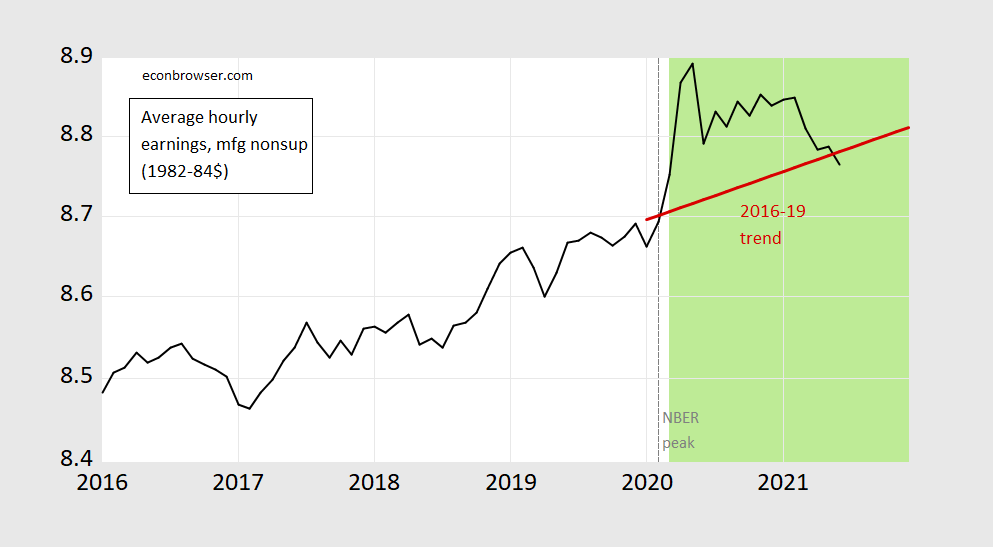

Figure 2: Average hourly earnings for manufacturing, production and nonsupervisory workers, deflated by CPI-all (black), and 2016-19 stochastic trend (red), both in 1982-84$. Source: BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

Figure 3: Average hourly earnings for accommodation and food services, nonsupervisory workers, deflated by CPI-all (black), and 2016-19 stochastic trend (red), both in 1982-84$. Source: BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

CPI deflated manufacturing wages are falling and below trend, while accommodation and food services are rising and above trend. Accommodation and food services on the other hand are still rising (through May) and above trend — but only by 1%.

Update, 5:15pm:

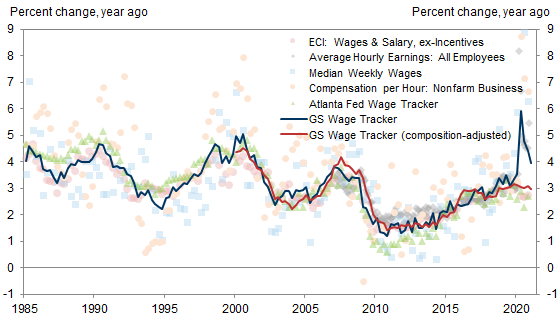

Two months ago, Goldman Sachs published a graph with their composition adjusted (nominal) wage series, which (at the time) suggested slower wage growth than the reported series.

Update, 7/17 1:15pm Pacific:

Atlanta Fed has a “wage tracker”, that’s incredibly useful. It’s based on CPS, a different data set than the household or establishment labor market surveys. Here’s hourly wages for hourly, non-hourly, and all workers.

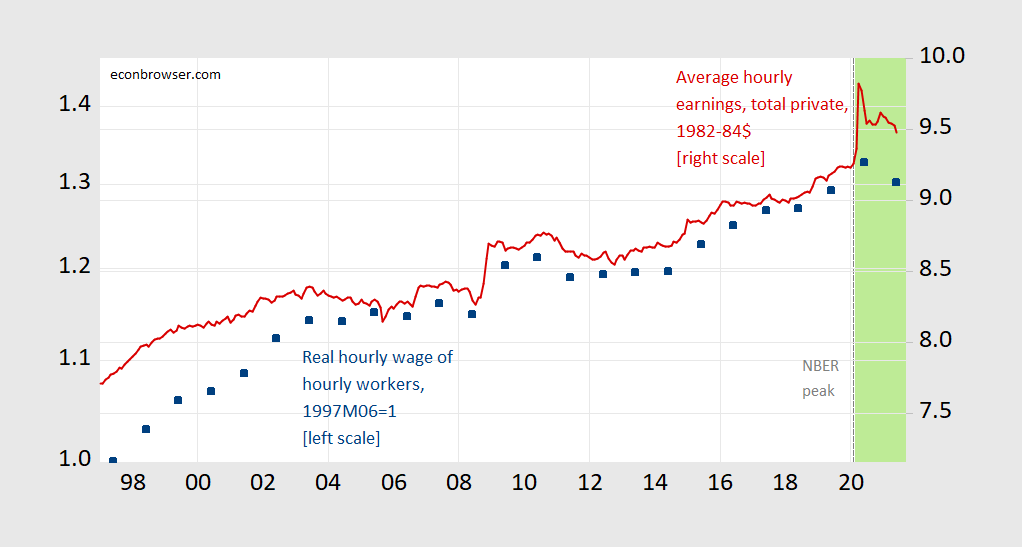

Here’s a comparison of real wages from establishment survey for all workers excluding nonproduction and supervisory (hourly, salaried, etc.), all hourly wages of hourly workers from CPS [blue squares].

Figure 4: Index of hourly wage of hourly workers based on median wage growth, deflated by CPI-all (blue square, left log scale), and average hourly earnings for total private industry excluding nonproduction and supervisory workers, deflated by CPI-all (red line, right log scale). Source: BLS via FRED, Atlanta Fed wage tracker, and author’s calculations.

One could interpret this evidence as reflecting the various changes in the demand and supply for certain types of workers. In other words, real wages are reflecting traditional microeconomic forces rather than responding to some alleged monetary aka expected inflation factor.

The idea that tight labor markets lead to wage gains is in line with historical evidence. The idea that inflation necessarily accelerates as wages rise is less clear, and amounts to an assertion that private sector managers are helpless in the face of change. Expenditure to increase productivity in order to offset wage increases is not considered? Profit compression is not considered? This helpless outlook is not consistent with heroic claims made to justify the high pay granted to top-level managers nor is it consistent with marginal analysis as taught in textbooks.

In fact, total compensation for civilian workers has risen about 60% since Q1 2001, while the PCE deflator has risen only about 42%. It also looks to me like changes in consumer prices lead compensation in that period, rather than the other way around – but that’s just eyeballing.

Generals (policy makers) may want to fight the last economic war, but kibbitzers are often in thrall to some long dead economist. When’s the last time an upward wage-price spiral was spotted in the wild in North America?

[ Waves both arms high in the air wildly ] Teacher!!!! Teacher!!!! Hey!!!! Teacher!!!! I know!!!!! I know the last wage-price spiral spotted in the wild!!!!!

https://images.app.goo.gl/NRLm3GRwTGidcRkJ6

Eeeeks! Edward Bear has got his head stuck in a BAD honey pot this time.

The idea that tight labor markets lead to wage gains is in line with historical evidence. The idea that inflation necessarily accelerates as wages rise is less clear, and amounts to an assertion that private sector managers are helpless in the face of change. Expenditure to increase productivity in order to offset wage increases is not considered? Profit compression is not considered? This helpless outlook is not consistent with heroic claims made to justify the high pay granted to top-level managers nor is it consistent with marginal analysis as taught in textbooks.

In fact, total compensation for civilian workers has risen about 60% since Q1 2001, while the PCE deflator has risen only about 42%. It also looks to me like changes in consumer prices lead compensation in that period, rather than the other way around – but that’s just eyeballing.

Generals (policy makers) may want to fight the last economic war, but kibbitzers are often in thrall to some long dead economist. When’s the last time an upward wage-price spiral was spotted in the wild in North America?

I think the biggest issues are compositional. For manufacturing, they laid off their lowest skill lowest paid workers and tried to retain their higher skill higher wage workers. So the composite wages rose. As they hire back the lower wage manufacturing workers, the composite returns to trend.

For food service workers, all of the higher end, higher paying restaurants were closed. The low wage fast food over the counter restaurants were the only ones open. So the composite wages fell. But after some time off, these low wage workers have realized just how horrible and crappy these jobs are, requiring wage increases to return. In order to survive the layoffs, they have had to make a lot of adjustments to their living standard. As the economists would say, with this new knowledge, they have decided that their leisure time is worth more than $7.50 per hour.

The Atlanta wage tracker seems to indirectly hammer home again the stance that this is transitory inflation, largely caused by supply issues, and probably a type of “con job” on the American consumer that prices are rising, so they should “tolerate” paying more for things, which in fact there is very little logic on the price rise. Who is going to tell me housing/construction demand has changed that much to explain the gyrations in lumber prices?? And I would even argue oil (though the argument is not as strong there as for lumber). I don’t think even Menzie or the great Alan Blinder could persuade me to change my views on that. Lots of this is just a con job on the American consumer by people saying we should have “inflation” here “well, uh, ‘because’ “.

Folks, to have “shortage in labor” you need legit persistent wage gains. Anyone who tells you that persistent wage gains are there, has just gotten you to bite down on a nasty barbed fish hook.