From EconoFact (update of May 2021 version):

Main points:

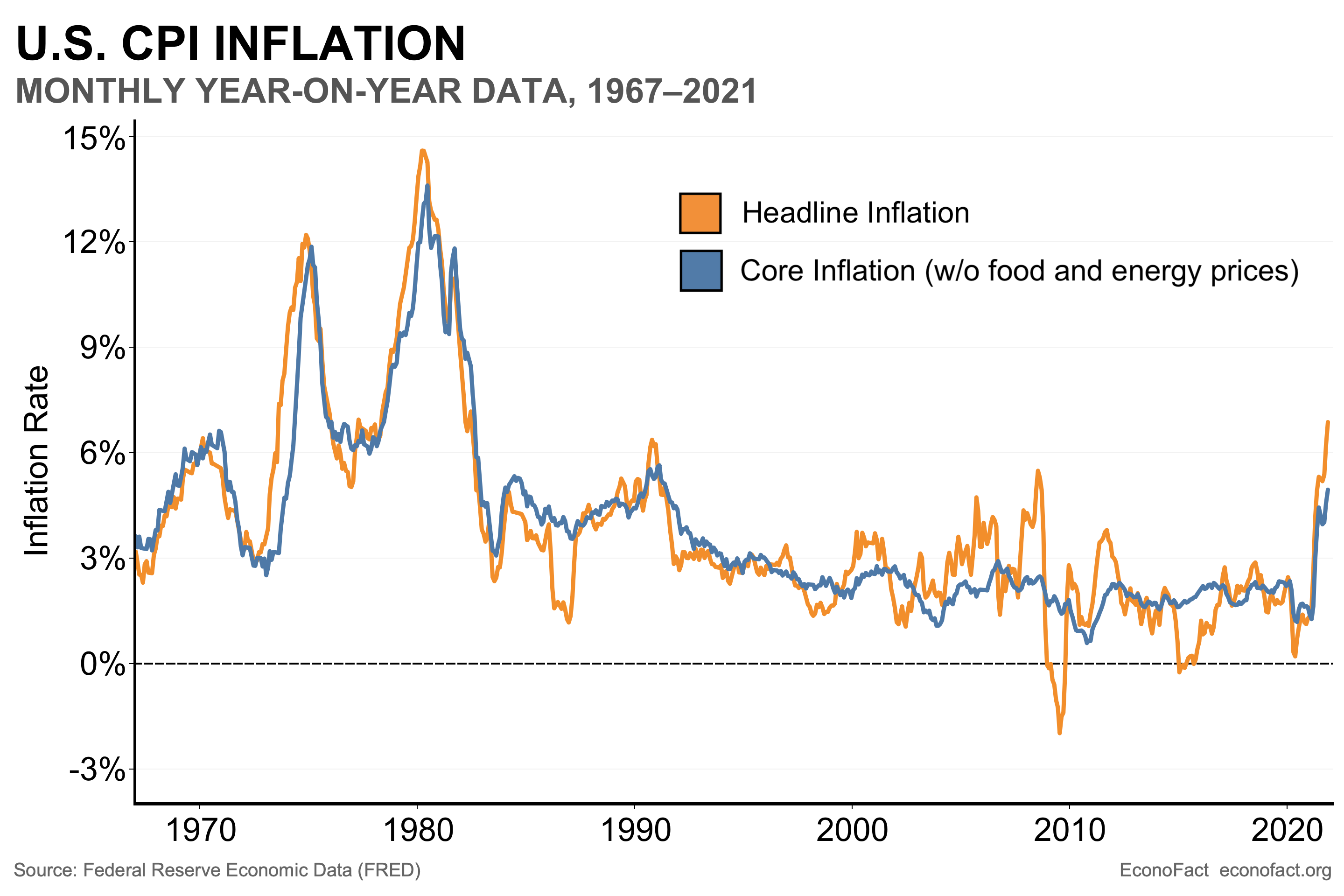

- Prior to the pandemic, inflation had been relatively low for about three decades, and especially quiescent over the past decade.

- Inflation has been rising over the past year, but this comes after especially low inflation in the immediate wake of the onset of the pandemic.

- In order to consider whether inflation is likely to continue at high rates, it is important to look at the different factors that contribute to a generalized rise in prices. Economists’ preferred explanation for inflation, sometimes called the “expectations augmented Phillips curve”, looks to some combination of three factors: slack, expectations, input costs.

- How much slack is there in the economy?

- Economists and households are marking up their expectations of inflation over the next year – although there is a divergence in views between the two groups. While in the relatively longer-term, financial markets project only a slight acceleration in inflation over the next five years.

- Is the cost of inputs likely to continue rising?

- Will labor costs continue to rise?

- Will too much money chasing too few goods cause inflation?

From “What This Means”

Inflation — both actual and expected — matters. Inflation makes it harder for consumers and workers and firms to distinguish between relative and general price changes. It also makes it more difficult to make plans for saving and investment. And, higher expected inflation raises borrowing costs for the government (although higher actual inflation erodes the real value of government debt). Finally, the Fed tends to respond to higher inflation by tightening monetary policy, which depresses economic activity. Hence, the stakes are high for avoiding a sustained acceleration in inflation. So far, inflation has risen in a halting fashion, but remaining more persistently high than previously anticipated. Near term expectations of inflation have risen, but remain relatively muted – particularly amongst economists — either because the anticipated output gap or the responsiveness of inflation to the output gap are thought to be small, longer term inflation expectations remain well-anchored, or all three.

For discussion of expectations, see this post.

For discussion of alternative measures of inflation, see this post.

For discussion of the role of the goods/services distinction, and role of shelter costs, see this post.

EconoFact on alternative means of measuring inflation during the pandemic here (Cavallo & Kryvtsov), on food price inflation here.

“Prior to the pandemic, inflation had been relatively low for about three decades”

We did see a temporary rise in headline inflation in early 2008. Now this could not be attributed to excess aggregate demand as we were already in a recession but it could be attributed to the commodity boom back then. And as I recall we also saw a spike in shipping costs which later retreated.

Perhaps the following question has been answered here or elsewhere, so I ask for some indulgence for my ignorance.

Using the Y/Y percent change in PCE Core, why has the difference between PCE Core Y/Y inflation and GS10 declined from about 7.4% at 1984m12 to negative 2.5% as of 2021m10? Negative values started appearing in 2012, then positive values until 2016, with a few negative months in 2019 and then constant negative values since 2020m01. Older data from the 1960s and 1970s show positive differences but for a few negative differences in 1974 and 1975.

The current ten-year inflation expectation, as calculated by the Cleveland Fed, is 1.75%, below the Fed target: https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/our-research/indicators-and-data/inflation-expectations.aspx

The current 5-year/5-year forward inflation price is 2.07%, essentially at the Fed target: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T5YIFR

Ten-year TIPS breakeven 2.40%, before adjustment, with recent adjustments running about -30 bps to -40 bps (Menzie?).

So the Fed has not lot much ground on inflation expectations in the longer term, whatever may be going on in the near term.

Slack? Depends on Covid and adjustments to labor market structure to encourage labor market participation.

Other input costs? Depends in large measure on a return of demand to a more services-heavy mix -which depends on Covid.

Why not explicitly insure everyone against inflation, by (for example) paying inflation plus 2% on individual Fed CBDC accounts?

That’s it. I get a guaranteed return on financial instruments that are not even part of my portfolio? No other real effects from unexpected inflation? This thread of yours is even more stupid than your confidence interval nagging.

Don’t unexpectedly even bother.

He’s either trying [and failing] to be facetious or he actually is that stupid.

Anyhow, Capitalism Is The Unknown Ideal. The US’s is a mixed economy: statism and capitalism, command/control and markets. For the past, emergency 20 months, statism has ruled. And, unexpectedly we get hit with ‘unexpected’ inflation.

International economy locked out; The Fed printed $4 trillion; and the Treasury added $8 trillion to the national debt

WHO COULD POSSIBLY HAVE SEEN INFLATION COMING?

Couple of reasons. One is that the effects of inflation are general, not specific to saved money. Protecting one economic activity, saving, while not protecting others is unfair.

The other is that some forms of inflation indexing make inflation more persistent. Fairness requires widespread indexing. Widespread indexing promotes inflation.

But, rsm, with all those humongous standard errors on all estimates of inflation, how will the Fed or some other body of the government know what to pay the citizens? I mean, you sure have convinced me that we have no reason to believe a single number coming out of anywhere in the government, so surely there will be no basis for engaging in any action at all based on these clearly totally unreliable numbers!

https://jabberwocking.com/it-sure-doesnt-look-like-high-inflation-is-a-permanent-thing/

Kevin Drum notes R. Glenn Hubbard is advocating only modest monetary restraint as opposed to Larry Summers who seems to be arguing for Volcker style tight money. Go figure – Hubbard being more of a dove than Summers.

Kevin attempts to use TIPs v. nominal interest rates to derive the market’s expectation of inflation over the next 10 years but me thinks his graph is quite confused. If anyone else can explain WTF Kevin is graphing – let us know.

If the price of crude and natural gas were to halve, immediately, how much would that drop the headline rate of inflation? Enough so the gold was now below the blue?

I’m not sure how these statistics work, in terms of wholesale versus retail pricing, but just make some clarifying assumption. (Like 90% of the benefit accrues to retail, or just halve retail prices themselves, if needed.) I’m not that keyed up on the retail specifics here. I just really want to know how much such a change would drive the overall number. Order of magnitude. Both crude and natural gas are markets with huge near term elasticity, such that additional supply (or the credible future promise of it) might drop the prices markedly. (Look at 1986, 2014, 2018, etc. for supply driven oil price crashes, when OPEC/SA was briefly dissuaded from price control to defending market share.)

I guess there’s also some multiplicative impact. Crude is a factor of production for transport and chemicals and the like, not just motor gasoline. And natural gas for electrical power. So, I donno. What would be a back of the envelope multiplicative impact (2x?) for the near immediate impact on other goods/services. And then how much does it drop the total (not core) inflation number?

Eh…just noticed that the post before this partially addressed my oil and gas thought experiment. Just me not reading the macro posts. Like micro (industry analysis) better than macro, just my casual interest of what I read. Just honestly more entertaining to me to see industry supply demand analyses than latest macro stats charts.

Still, very intrigued by the possible benefits to both inflation and economic growth, if the investment climate for shale were to change. Robert Clark shows a good indicator (activity versus price) that “buggy whip” companies are requiring higher hurdles for investment, under Biden.

https://twitter.com/RobertClarke_WM/status/1453017667137323010

Doesn’t mean zero activity. Just a higher hurdle. E ven with “fast response” shale, lots of activities (pads, roads, gathering lines, seismic shoots, hiring geologists, etc.) have medium term investment return outlooks. And it matches what I see from investor reactions to capex and company behavior and discussions in the field. If we could change back to “irresponsible” growth, that flares up every time crude gets north of $50-$60, it would have major impact on world prices. I think at this point, I’ve won the argument with Hamilton that ex-cartel competition can destabilize cartel propped up price. That US production is significant. That shale matters more than he thought it would.

Note that the impact would be different from a supply-driven price drop (e.g. more shale, OPEC+ collusion cracks) versus a demand drop (e.g. more Covid, recession). In particular, US activity would have an impact on the oil services sector, as activity increased substantially. Although a decent case can be made that leaseholders, at least those who’ve already gotten upfront bonuses and had most of their wells completed and are reliant on already drilled production revenue, are better off in a world where OPEC+ can effectively raise price to $80, versus say $50. Same thing for stripper well operators, probably. For companies still exploring/developing, would be more mixed impact on their valuations–damage from lower price outlook, but benefit of less probable danger from future regulations or God help us, export controls, windfall profits taxes, etc. But for oil service providers, midstreamers, and consumers(!), benefits are pretty clear.

And in any case, the Persian Gulf has hugely productive oil resources, so I think true true free competition would have prices down below $40, which shale can’t compete at, regardless of the US political/regulatory specter. So even with an unleashed shale, OPEC still has impact. But pretty clearly, if the US starts pumping 13 MM bopd and threatening 1MM bopd+ per year, headed to north of 15 MM bopd, it affects OPEC+ policies. UAE oil minister even said this in 2019–all bets are off if the damned US pumps 15.

A lot of the same dynamics apply with natural gas production, but with the difference of no OPEC+ to contend with (really is a free competition market, at HH). And with the major impact funneling down to natty users like chemicals, steel, etc. which can acquire a competitive benefit versus others when they are getting sub $3 HH. (All that said, currently spot for natty in Asia and Europe is insane. So, it doesn’t matter that much, compared to $20+ if we are $3 or $5. But medium-long term outlook may be a different thing.)