Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan-Boul, Professor of Economics at the University of Houston and Economics Lecturer at Stanford University.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) adopted its first Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in January 2012. The goals of the statement were to mitigate deviations of inflation from its 2 percent target and deviations of employment from its maximum level. In August 2020, the FOMC adopted a far-reaching revised statement. The revised statement contained two major changes from the original statement. The FOMC would implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time” and policy decisions would attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. In August 2025, the FOMC abandoned FAIT in favor of Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) and downplayed shortfalls, essentially returning to the 2012 Statement.

In our paper, “Alternative Policy Rules and Post-Covid Fed Policies,” recently published online in The Economists’ Voice, we analyze Fed policies between 2020:Q3 and 2027:Q4 using a variety of policy rules and compare the policy rule prescriptions with the federal funds rate (FFR) between 2020:Q3 and 2025:Q2 using the most recent data and with the projected FFR between 2025:Q3 and 2027:Q4 using inflation and unemployment projections from the June 2025 Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). We show that FAIT was irrelevant and shortfalls were relatively unimportant. In this post, we discuss the paper and extend the results through 2028:Q4 by using inflation, unemployment, and FFR projections from the September 2025 SEP.

The 2020 Statement was adopted following a decade of low growth, low inflation, and low interest rates. The 2025 Statement was adopted in a very different environment. While there is great uncertainty about the future path of the economy, returning to the world between 2012 and 2019 appears unlikely. Replacing FAIT with FIT and adding ambiguity to shortfalls seem like steps in the right direction.

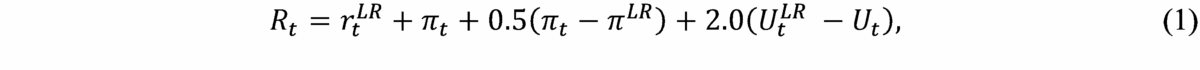

Starting with Taylor (1993), policy rules have become the standard method for analyzing Fed policy. The Taylor (1999) and Yellen (2012) balanced approach rule with an unemployment gap is as follows,

where Rt is the level of the short-term federal funds interest rate prescribed by the rule, πt is the inflation rate, πLR is the 2 percent target level of inflation, ULRt is the rate of unemployment in the longer run, Ut is the current unemployment rate, and rLRt is the neutral real interest rate that is consistent with inflation equal to the target level of inflation and unemployment equal to the rate of unemployment in the longer run. The Taylor (1993) version of the rule has a coefficient of 1.0 on the unemployment gap.

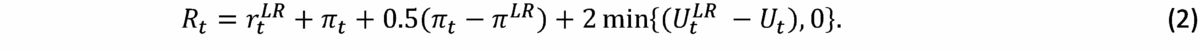

The balanced approach (shortfalls) rule mitigates employment shortfalls instead of deviations by having the FFR only respond to unemployment if it exceeds longer-run unemployment,

If unemployment exceeds longer-run unemployment, the FFR prescriptions are identical to those with the balanced approach rule. If unemployment is below longer-run unemployment, low unemployment does not contribute towards the FOMC raising the FFR.

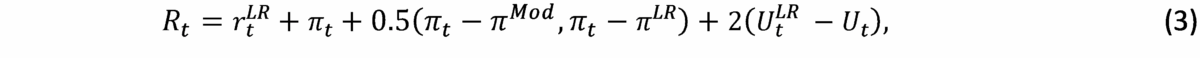

The balanced approach (FAIT) rule is,

where rLRt is the neutral real interest rate, πLR = 2, Mod represents the rate of inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time in the revised statement and is the rate of unemployment in the longer run. The FAIT rules differ from the original rules because the prescribed FFR does not increase until inflation is moderately above 2 percent for some time.

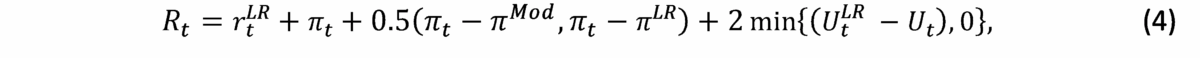

The balanced approach (consistent) rule is,

where is the neutral real interest rate, = 2, and πMod represents the rate of inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time in the revised statement. The consistent rules combine shortfalls and FAIT.

According to the policy rules in Equations (1) – (4), the FFR fully adjusts whenever the target FFR changes. We also specify inertial versions of our policy rules based on Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999) and Sack and Wieland (2000),

where p = 0.85 is the degree of inertia and is the target level of the federal funds rate prescribed by each of the policy rules in Equation (1) – (4). Inertial rules have the advantage that they lower the variance of the FFR in response to changes in inflation and unemployment gaps. equals the rate prescribed by the rule if it is positive and zero if the prescribed rate is negative.

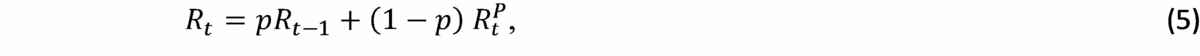

The results for the non-inertial and inertial balanced approach rules are reported in Figure 1. Since the Taylor rule prescriptions are similar to the balanced approach rule prescriptions, we only include the latter in the post. Annual Core PCE inflation was between 1.3 and 1.5 percent from September 2020 through March 2021 and rose to 3.1 percent in June 2021. Since 3.1 percent is clearly more than moderately above 2 percent, there is no difference between the prescriptions with the original and FAIT rules after March 2021. In addition, the prescriptions from the original and FAIT rules are negative between September 2020 and March 2021 and set equal to zero by the ELB. Taken together, prescriptions from original rules are identical to prescriptions from FAIT rules. Figure 1 also reports the results for the shortfalls and consistent rules. Since the prescriptions from the FAIT rules are identical to the prescriptions from the original rules, the prescriptions from the consistent rules are identical to the prescriptions from the shortfalls rules.

Figure 1. Original (FAIT) and Shortfalls (Consistent) Policy Rule Prescriptions

Panel A. Non-Inertial Balanced Approach Rules

Panel A reports the results from the non-inertial rules. With either original (FAIT) or shortfalls (consistent) rules, the prescribed FFR is greater than the actual FFR from 2021:Q2 to 2023:Q3 and less than the actual or projected FFR from 2023:Q4 to 2025:Q2. Starting in 2025:Q3, the prescribed and projected FFR’s are very similar through 2028:Q4. Prescriptions from the original rules are equal to those from the shortfalls rules between 2020:Q3 and 2021:Q4 and between 2025:Q2 and 2028:Q4 because unemployment is greater than or equal to longer-run unemployment. Between 2022:Q1 and 2025:Q1, prescriptions from the shortfalls rules are lower than those from the original rules because unemployment is less than longer-run unemployment.

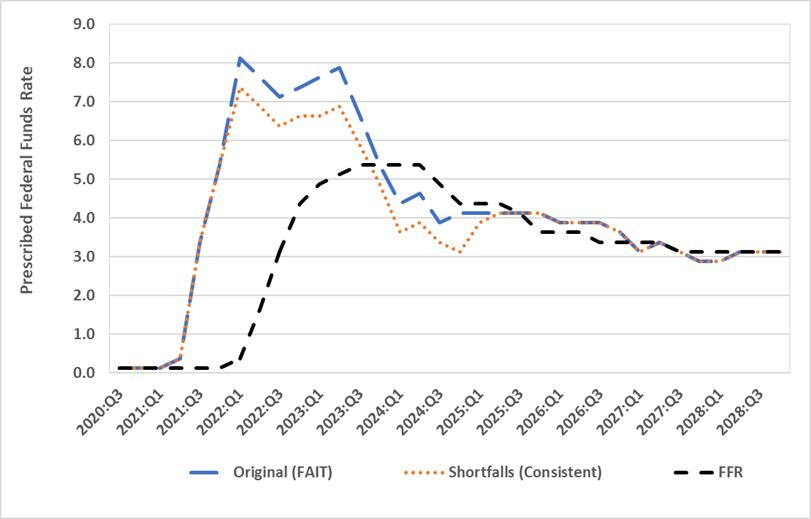

Panel B reports the results from the inertial rules. While the prescribed FFR is higher than the actual FFR from 2021 through 2022, the differences are much smaller than with the non-inertial rules. Prescriptions from the original rules are generally closer to the FFR than those from the shortfalls rules in 2023 and 2024. Starting in 2025:Q3, the FFR projections are consistently below the policy prescriptions through 2028:Q4.This is very different than with the non-inertial rules, where the prescribed and projected FFR’s are very similar.

Figure 1. Original (FAIT) and Shortfalls (Consistent) Policy Rule Prescriptions

Panel B. Inertial Balanced Approach Rules

This post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan-Boul.

I’m not too bothered by the authors’ conclusions, but I have a problem with the way they got there.

“While there is great uncertainty about the future path of the economy, returning to the world between 2012 and 2019 appears unlikely.”

As a statement about time travel, yes, this is correct. As a statement about the inflationary trend, this is arrogance – obvious arrogance in the context of the history of monetary policy frameworks. The central bankers who created FAIT did not seem to anticipate an end to the low-inflation environment they faced. Central bankers in the prior period of higher inflation do not seem to have anticipated a period of persistent below-2% inflation. Yet the authors seem to tell us that a return to a below-2% inflation environment is unlikely. Is this anything more that academics behaving like common folk in expecting that past performance will persist? As a mere aside, this would be a funny lapse. As a premise in an argument, it’s unacceptable.

Jim Bullard’s notion of inflation “regimes” should be familiar to the authors. Bullard makes no claim to know the future trend of inflation. Instead, he argues for taking the current regime as given and relying on the data to tell us when the regime changes. That’s an admirably humble way of thinking.

“Since 3.1 percent is clearly more than moderately above 2 percent, there is no difference between the prescriptions with the original and FAIT rules after March 2021.”

“…clearly more than moderately above 2 precent”? By what standard? Public ire? The preferences of some elite group. Where, in the empirical literature, is there evidence that inflation of 3.1% produces a welfare loss relative to inflation of 2.0%? If the claim that 3.1% is very different from 2% is essential to the conclusion that the two policy rules are not different in their results, then the analysis fails.

I don’t have any way of judging the numerical analysis presented here, but I assume the math is good. If, however, the conclusion drawn from the math depends on assumptions like the ones I’ve quoted, then no amount of math can persuade me of the conclusions.

The authors’ assumptions appear to be drawn from conventional wisdom. Nobody should be comfortable with that.