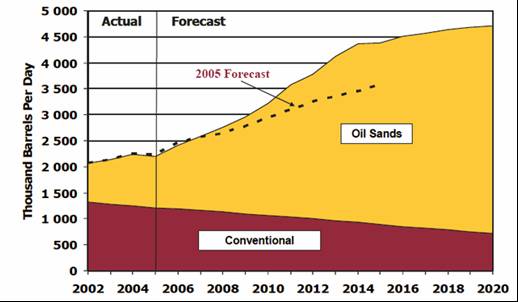

The phenomenal boom of Canada’s oil sands industry continues, despite the complete absence of any government crash program to cope with peak oil.

Via Green Car Congress, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers new projections call for Canada to double its production of crude oil by 2020, thanks to rapid expansion of the Canadian oil sands resource. CAPP’s new projections for 2015 are 750,000 barrels per day higher than they were projecting just last year, and call for nearly 5 million barrels per day (mbd) Canadian production by 2020.

|

It’s interesting to compare these new projections with the assessment made in last year’s report by Robert Hirsch and co-authors on prospects for mitigating peak oil:

The current Canadian vision is to produce a total of about 5 mbd of products from oil sands by 2030. This is to include about 3 mbd of synthetic crude oil from which refined fuels can be produced, with the remainder being poorer quality bitumen that could be used for energy, power, and/or hydrogen and petrochemicals production. 5 mbd would represent a five-fold increase from current levels of production. Another estimate of future production states that if all proposed oil sands projects proceed on schedule, industry could produce 3.5 mbd by 2017, representing 2 mbd of synthetic crude and 1.5 mbd of unprocessed lower-grade bitumen.

The Hirsch report was concerned that this pace was much too slow, and advocated a crash program for acceleration:

The pace that governments and industry chose to mitigate the negative impacts of the peaking of world oil production is to be determined. As a limiting case, we choose overnight go-ahead decision-making for all actions, i.e., crash programs. Our rationale is that in a sudden disaster situation, crash programs are most likely to be quickly implemented.

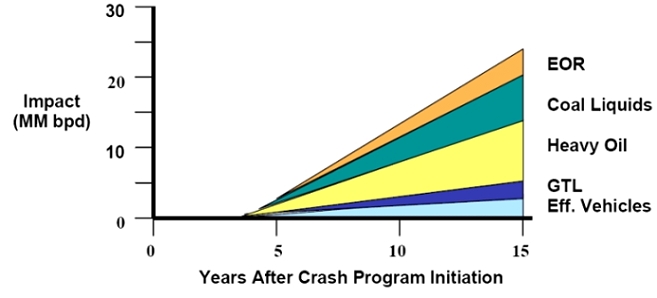

The heart of the Hirsch analysis was based on the idea of “wedges”, or the notion that even if a crash program were implemented today, with the long lead times for many of these projects, even after a number of years they would still be making a relatively minor contribution. Canadian oil sands represent one component of the wedge labeled “heavy oil” in Hirsch’s diagram below.

|

I had the opportunity to meet Bob Hirsch at a conference a few weeks ago, and liked him very much. He is sincere and passionate in his commitments, and open and thoughtful in discussion. He is certainly correct that there are enormous lead times involved in these technologies, and that even with the accelerated development, oil sands could only make a modest dent globally in offsetting a rapid decline rate from conventional crude production.

|

Even so, I am struck by the fact that, at least for oil sands, his “crash program” is already being implemented. And it’s happening not because somebody argued persuasively that it needed to be done, but rather because producers found that by doing it they could earn huge profits. As I’ve said before, the profit motive is an incredibly powerful incentive, a far more effective force to change the world, for better or worse, than the exhortations of the most passionate and informed advocate. Those who seek to change the world would be wise to consider how to marshal this force to be working with them on their side.

Some economists talk about the forces that determine the supply and demand for “widgets”. I think we may have something to say about “wedges” as well.

Technorati Tags: peak oil,

oil sands,

Hirsch report

1. Peak Oil is a hypothesis.

Global climate change and CO2 accumulation is far more certain, scientifically.

The problem with the tar sands is the level of CO2 production is extremely high– something like 4 times, per barrel of oil produced and consumed, than that of oil produced by conventional methods. The total contribution to world CO2 levels could wind up being quite significant.

So a ‘crash programme’ to produce oil from tar sands could wind up drowning us in CO2.

2. security of supply is worth a lot. Outside the US it is hard to find more accessible, politically stable oil production sources

3. the barrier to expansion in the Alberta Tar Sands is physical– resources of water and most importantly any kind of skilled labour are desparately short. This is an industry that hasn’t hired in 15 years, and Fort Macmurray is not exactly an attractive destination for new graduates.

It wouldn’t be physically possible to scale up production any faster than is planned. In fact, the existing projects are likely to have big cost overruns.

4. Long run, there is a real concern that there is not enough natural gas to produce the required oil– about 0.8 mcf per barrel of oil. There has been talk of building a nuclear reactor up there to produce the steam.

From an investor standpoint it’s great. From a consumer standpoint, I have to wonder how many more situations there are like this in the world.

Canada has an exploitable resource, with proven production technology, a stable (and environmentally flexible) government, a short pipeline from major markets.

Hirsch is concerned with the global scale. Are there enough similar ‘investor opportunties’ to provide all the ‘wedges’ global consumers need?

The “huge profits” are due in part to (almost) free externalities allowed the producers. That is, the environmental degradation of sands exploitation will likewise be “huge.”

A nuclear plant adjacent to the oil sands refineries would be the ultimate co-gen. The steam would replace the huge quantity of natural gas now being burned to heat the bitumen, and the electicity would not only support the growing infrastructure and population in the area, but could also replace fossil fuel burners in southern Alberta.

The Premier of Alberta (who in any event is retiring and will be gone by the end of the year) had rejected plans for a nuclear plant as recently as last summer, but in the past few weeks has said that he is open to the idea.

As pointed out above, one the big problems would be finding labour to build a plant. Pretty much everyone who can pound a nail or swing a shovel is already making big bucks in the oil fields, the housing business or the infrastructure projects. There is much talk of bringing in guest workers,particularly in the more skilled trades.

Those who seek to change the world would be wise to consider how to marshal this force to be working with them on their side.

Being one of the local contrarians regarding market forces, I would suggest that these forces have led us into the present pickle. How to harness greed? Can we? I dont think so.

On this score, what sane energy policy has this greed left in its wake? Have deregulated market forces left us with any kind of policy, environmental or otherwise?

Aside from being obstructionist regarding global warming and aside from telling us that adequate oil supplies extend far into the future, what have these forces achieved?

Some have already pointed to the trail of environmental wreckage this latest endeavor is creating. Others have correctly observed that the tar sands simply cannot produce enough. It will not wash.

With the completed privatization of Petro-Canada, the Canadian government lost control of its own energy policy. Does the U.S. have one?

Greed is fine for those who benefit in the short-term; but as a long-term policy, it sucks. Regulation and vision work much better.

Maybe when survival is on the line, we will find a better motivation.

Stormy wrote:

“Being one of the local contrarians regarding market forces, I would suggest that these forces have led us into the present pickle…..what have these forces achieved?”

Ever seen Life of Brian?

Odograph

Not many. Venezuela has a similar scale oil resource (different chemistry of oil and sand, but the same idea) but is too politically unstable to allow long term development. They just effectively nationalised their foreign partners in the development.

Coal to liquid and gas to liquid are out there, and practicable. But hard to scale, and very big CO2 consequences.

The real energy ‘opportunity’ is conservation. Whilst US gasoline prices are so unrealistically low, this is not going to be a big enough factor. An SUV built now will last for 17 years on average, in the hands of some poor immigrant who buys it, even if its suburban owner ditches it tomorrow for a fuel efficient Prius.

I noted hybrid sales in the US are wilting. Outside of a group of core buyers, the price premium is still too great. What you need are European numbers of diesel cars– roll on low sulphur diesel fuel!

There are other alternatives ‘let them ride motorcycles’ if things get really bad. But they are not bad enough yet. My guess is the US will need to see at least $5/gallon.

I don’t think ethanol is a viable large scale option, btw. At the moment what we seem to be doing is accelerating global warming, by killing off the Amazon faster to make Brasilian ethanol. Clean politics, but dirty air.

I resemble that remark! (as a middle class Prius owner)

For what it’s worth though, hybrid sales swing with the gas prices. Latest news is that used Prius are selling above at above new prices, as the new ones go missing again:

“For example, a 2005 Toyota Prius that, when new, had a sticker price of $21,515 could now sell for $25,970, even with 20,000 miles on the odometer, according to data from Kelley Blue Book. Since Toyota dealers usually charge a few thousand dollars over sticker for new Priuses, the buyer in this example probably wouldn’t have made a profit, but nearly so”

http://www.cnn.com/2006/AUTOS/05/17/used_compacts/

Odo – that’s awesome! Amazing how people, when given the choice, will vote with their wallets….

Speaking of which – did anyone see GM’s new “gas price” rebate plan? Basically they’ll pay the difference between pump price and $1.99 per gallon for people who buy a new SUV and other products…catches – for one year, you’ve got to buy OnStar and the deal’s only good for a year….interesting marketing gimmick

BTW, on ethanol, I was the partial instigator on this piece, and hesitate to mention it … but on the other hand it sure plays into the main point up above, about how incentives are driving energy business:

http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/5/23/23846/0807

Odo

Re ethanol – now available it DIY kits for the home brewer….

http://www.ethanolstill.com/

You know….if the kinks get worked out on this sorta thing and it becomes a popular home activity, all sorts of interesting implications….

For those unfamiliar with odograph’s link, here is the bottom line:

“Converting 100% of the corn crop into ethanol, presuming we had a market for the byproducts, would then displace an incredible 2.0% of our annual gasoline consumption.”

http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/5/23/23846/0807

No more popcorn or corn on the cob. Sigh.

And now we have farmers rushing like rats to the next piece of cheese: Market forces at work.

The whole thing is like watching a blind, deaf, sense-less rat trying to bump its way out of a maze.

Market forces sometimes are akin to evolutionary forces: Keep trying all the possibilities…something is bound to work, given a few million years or so. We should have so much time. 🙂

“Market economies are not self-regulating. They cannot simply be left on autopilot, especially if one wants to ensure that their benefits are shared widely.”

Stiglitz April 2006

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/stiglitz69/English

Stormy

We’re to assume you’re typing on a homemade computer using software you coded yourself and powered by self-generated electricity while eating homegrown fresh fruit, etc etc?

On this score, what sane energy policy has this greed left in its wake? Have deregulated market forces left us with any kind of policy, environmental or otherwise?

Market forces, and greed have more to do/affect with/on supply. These forces really do not deal with the environmental aspect, or some political platform/policy. Those are separate. Plus when governments see the potential tax dollars, jobs, or short-term political damage from high oil prices then their policy will be to dig that sand as fast as possible.

Regulation and vision work much better.

Regulation? You mean like blocking Cape Wind? Or, here in Maryland where regulators want to prevent market based electricity rates so people will have no incentive to consume less? Truly visionary policies.

“On this score, what sane energy policy has this greed left in its wake? Have deregulated market forces left us with any kind of policy, environmental or otherwise?”

What sane (by your definition) long term energy policy has been developed anywhere without market forces? Communist countries were much dirtier and had many more supply problems. Can you point to a large country with a sane (by your definition) energy policy? Economics is about alternatives.

Nice work.

A long time ago I had a very junior engineering management position for 9 months on the Exxon/TOSCO Colony Oil Shale project . . . what started out as approx. a $4-$5 billion mega-project in 1979 quickly escalated to an $8++ billion albatross project by March 1982 and was completely shut down by Exxon after spending some $1 billion of shareholders money.

Mega-projects are very lumpy, risky and exposed over very long timeframes to exogenous factors that can’t be anticipated.

I was always amazed at the amount of over-investment the oil energy put in place in the 1970s and 1980s even in the face of windfall profits taxes, nationalization of resources and other negative forces – it seemed imprudent to me.

Kind of like the story of the oilman who died and got stopped by St. Peter at the pearly gates because heaven “was full up with oilmen”. So the oilman thinks for a minute, cups his hands and hollers “oil discovered in HELL !!”. There’s an immediate rush of oilmen flying out of heaven and headed for an eternity of wildcatting in HELL. And St. Peter is amazed when the oilman at the gates turns around and heads off after the crowd, and asks him, “Sir, we have plenty of room now for another oilman, why are you leaving?” and the oilman calls back, “well, now that I think about it, there may be something to that rumor after all!!”

If we really were serious about cranking up production from the oil sands, what we ought to do is put together a program that takes away some of the risk – that is, oil sands are a very high cost operation and have enormous, lumpy fixed costs and the price of oil has been very volatile in the past 5 years – despite these obstacles, there’s already been considerable development – but what would happen if the US government gave oil sands companies a guaranteed floor price on their production of maybe $35 per barrel for a decade or so? I think you’d likely get a heckuva lot more development and IMHO not have to spend a dime on the guaranteed floor.

I felt a sense of disagreement with James Hamilton’s original article above, but only because I felt “good” government action is better than no action. Of course, as shown by the ethanol link, etc., we have a lot of “bad” government action that makes his no action look good.

So I guess despite wanting to disagree, I agree.

FWIW, I started somewhat suspicious of specific energy subsidies, but was convinced to support “no production subsidies” by this paper from October 29, 2003, by Jerry Taylor from the Cato Institute and Dan Becker from the Sierra Club.

http://www.commondreams.org/scriptfiles/views03/1029-07.htm

I’d argue for some dirty-fuel taxes, and some research monies maybe … but sure, I got on the “no subsidy” bandwagon way back.

Market forces? Human nature?

We cannot misunderstand human nature. Sooner than later, even among equalitarian communists the privileged few ended having blatantly more possessions than their peers.

(How would you explain otherwise, former (now in jail) Yuko’s owner attempt to sell his company to Exxon for several billion USD, when 10+ years ago the USSR state owned everything?)

But, this does not contradict establishing sound policies.

Nor does knowing that market force or greed has a fundamental role in the explanation of the efficient outcome of the development of a society.

History is replete with examples of suicidal societies destroying their environment and themselves. Papua New Guineans, Easter Islanders… Norwegian Icelanders, who ended one winter day starving by gnawing away their cattles bones…

Societies do need rules… and the police to enforce them… What would happen if we didn’t have the plain and simple traffic lights?

As a matter of fact, a good measure of a country’s progress is to ponder the maturity and development of their laws.

Sound, comprehensive, long range energy policy, which factors in human nature at its core, is desperately needed and lacking, –if not, there would be no point to this discussion.

Market forces loose no way.

Jon, Jon,

That is not what I am saying. I am not arguing “self-sufficiency.” Sheesh! Try reading the rest of my link to Stiglitz. Pay particular attention to his comments regarding China and environmental controls, the pressure China is now facing: short-term profits or environmental sustainability.

Odograph,

Yes, bad government action is highly questionable. We have encouraged a system that sees only short-term gains/profits: That includes politics and the media. Who controls the message? Who sets the agenda and the rules? How much power does K street have over the political process, over decision-making?

The system has been perverted, taken over, corrupted. When the national media put news on the same level as soap operas (profitability first), then the principles of economics took hold: profits.

I am old enough to remember when this happenedthe cries and warnings. They went unheeded. Economic principles prevailed. The news in the states is filtered, paid for, controlled. Fox is only an extreme example.

And I ask you: Should the news media operate on economic principles? As a democracy, we have lost our way.

To argue that because governmental policy is flawed with ethanolbecause of profit pressureswe must then conclude that the unregulated market place is better—that is a stretch.

Again, I refer you as well to the Stiglitz link.

Re Robert Rapier’s article at theoildrum.com mentioned above:

http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/5/23/23846/0807

The “bottom line” quoted by Stormy is not quite right:

“Converting 100% of the corn crop into ethanol, presuming we had a market for the byproducts, would then displace an incredible 2.0% of our annual gasoline consumption.”

This does not mean what you think it means. He is not comparing converting corn to ethanol vs. the status quo. Rather, he is in effect comparing converting corn to ethanol, which uses lots of natural gas, with a hypothetical where we instead used that NG directly to power CNG vehicles. In that case, the ethanol scenario is estimated to save 2% more gasoline than the direct NG usage scenario. Of course, nobody proposes to convert 100% of the corn crop to ethanol, but the point is that this is comparing two hypothetical extreme scenarios and should not be taken at face value.

There are many considerations that enter into creating more ethanol vs trying to use NG directly vs doing other things (like converting NG to methanol): distribution and storage of fuel, dispensing it into vehicles, changing engines to use the new fuel, etc. Generally I imagine that liquid fuels like ethanol or methanol will be more easily incorporated into the present infrastructure than large-scale conversion to CNG, electric or hydrogen power. So even if this is not quite as efficient as those other choices, it may still be a sensible approach.

Hal,

Robert Rapier has asked for a thorough peer review on his article. I would invite you to make your comments there. See how they fly.

He is a thoughtful and careful commentator, as his work in RealClimate will attest.

I would note that you, however, have not stated how much of a solution ethanol is. I am certainly willing to listen. Is Robert right in his 2% figure? How would you adjust that figure and why?

I look forward to your comments in The Oil Drum.

I would add the following Rapier comment:

“To do a true displacement analysis would be a massive undertaking. The above is an approximation. But the BTU equivalent calculation is not affected. It is the same regardless. The bottom line is that the amount of grain ethanol we can reasonably produce can’t justify this massive E85 campaign. It is a distraction, and lulls people into complacency.”

http://www.theoildrum.com/story/2006/5/23/23846/0807#more

Hal, there are two ethanol problems:

– source material

– energy of conversion

Now, to question “E85 everywhere” I don’t think you need to go into the details of energy conversion at all. With current technology there just isn’t the source material. The math for that is easy, back of the envelope, stuff.

Stormy

You rail against “market forces” and yet have no problem enjoying their benefits. If you wished the reader to consider other aspects of the Stiglitz link, you would have well-served to quote those instead of what you did choose.

Jon,

It is hard to know what exactly your substantive response is to any of my posts.

If I missed something in the Stiglitz link, cite it. If you think my characterization of present market forces as lacking any vision, feel free to argue the point. If I missed something concerning ethanol, argue that. (Ethanol is the example I am using regarding market forces.)

When science is politicized and when the media abdicates its responsibility, then market forces have a hard time working properly. We are constantly being sold a bill of goods.

Furthermore, without proper regulation, market forces can create dangerous economic imbalances. I am referring here to labor arbitrage, tax arbitrage, and environmental arbitrage–all of which are in powerful play globally: twin deficits, etc. I would argue that WTO rules regarding labor and the environment are exceedingly dangerous. They were designed to maximized immediate, short-term profitability. They were written only with business in mind, not labor or the evironment.

Stormy,

Tell you what – why don’t you answer two questions: You keep speaking of the need for “vision” as a regulating mechanism to trump market forces. Who’s vision? And why should I value it over that of my own?

Oh – and I agree – WTO rules *are* dangerous. WTO rules are NOT free market forces at work – these regulations and the like are products of governmental interference. If you believe examples like this and ethanol are truly representative of “free market forces”, then we’re simply speaking different languages.

Stormy asks, “How to harness greed? Can we? I dont think so…. Greed is fine for those who benefit in the short-term; but as a long-term policy, it sucks.”

If you believe, as Hirsch does, that the goal should be to develop the Canadian oil sands at a crash pace, then, I argue, greed has very much proven to be an effective force that can accomplish precisely that mission.

If you have a goal, as Jon assumes, of having available such items as a computer, software, electricity, and fresh fruit, then, as Jon points out, the greed of those who produced these items has very much proven to be an effective force that has accomplished precisely that mission.

And if you have a goal, as Valuethinker does, of reducing carbon dioxide emissions, then a carbon tax is exactly the way to harness the power of greed to achieve your goals. Put on the carbon tax, and the companies will figure out well enough to go with the nuclear option rather than natural gas.

JDH and others,

Appreciate your responses. Each of you use requires a tailored response. None of you are, except Jon, I think, for no regulations at all.

For example, ValueThinkers carbon tax: Perfectly acceptable proposal. But it is a regulation; as such, market forces (greed) are being guided by a higher vision. No problem from me on that score. However, that tax answers only the U.S. problem, and global warming is hmmmm global?

It is not just a U.S. issue anymore.

For that reason, I raise the WTO policy that eschews any interference in an individual countrys environmental policy. According to the WTO, as long as all players play by the same rules within a country, the WTO is satisfied. I am not.

If a country has weak or non-existent environmental standards, the WTO does not care.

This is what I mean by environmental arbitrage: leveraging the environment to obtain a market advantage. We are fast entering a world where this will be very foolish.

If you accept the necessity for regulations, then you have indeed put some kind of control on greedcontrolling it for the better good. You are beginning to exercise vision, which is a bit different from short-term market forces.

Regulations are a slippery slope. Accept one then on what basis you deny adding another? I am not suggesting a command economy, but I am suggesting that we need a to re-think exactly how market forces have led us into this pickle. Why is it that we have not seen beyond our noses? Why is it that suddenly these problems are upon us? Why is it that NAFTA has no environmental teeth? Or that developing nations entering the WTO were not required to have some kind of labor or environmental standards?

Like it or lump it, those regulations are going to pouring in en masse. There will be little alternative.

Then the question is: Is there a forum for real discussion on scientific merit, one to which the public has easy and common access. We need to know what precisely are the problems and what are the available solutions.

I do not consider the excellent sitessuch as this one–on the internet as such access. I am speaking of the national media, alas.

Regarding Jons computer and fruit comment, I find it just avoids real thought. Sorry. It always sounds cute to say: Hey, you benefited from the market forces! Well, I am not convinced that they have been in my long-term or my childrens best interest. Yes, I have my computer and my fruit. So? Going to buy me off with those things?

Does this mean that I tacitly accept the rightness of every dimension of the system? No, it doesnt. Does it mean I should starve? Nope. Does it mean I should not try to change the system? Come on!

Regarding the Hirsch report: Hirsch acknowledges the high price we may well pay for the oil sands. While it may mitigateor provide a wedgeover the hump, he acknowledges the huge environmental cost, to say nothing of the water and energy required to get that oil.

This White House has refused regulations in the name of free market forces. Doing so has been a terrible mistake. There has been no vision other than privatize everything. As the Hirsch report advises, we do not have a lot of time–and Hirsch is talking only about oil!

Hirsch did not draw upon climatologists for the other half of the equation: Global Warming. And that monster is not so easily mastered.

Stormy

Why do you assume I’m “for no regulations”? Did I miss you asking as I did you who’s vision we are to follow and why that should be valued more than my own?

As for fruit and computers – *why* did you choose to purchase them if you believe ownership is not in your personal best interest?

I applaud your desire to change the system – choice is a wonderful thing.

Jon,

I still have no idea why you assume I think ownership of computer and fruit is a bad thing or what deductions you are making because I own a computer and buy fruit.

Did I say I was against ownership? Nope. Did I say I was against privatization of everything. Yup.

I wish you would make yourself clear.

Let me ask you, just for kicks, do you think all roads should be privately owned?

He is not comparing converting corn to ethanol vs. the status quo. Rather, he is in effect comparing converting corn to ethanol, which uses lots of natural gas, with a hypothetical where we instead used that NG directly to power CNG vehicles. In that case, the ethanol scenario is estimated to save 2% more gasoline than the direct NG usage scenario.

That’s where the 2% number came from. Converting 100% of the corn crop to ethanol versus using that natural gas in CNG vehicles can contribute 2% net BTUs toward U.S. gasoline demand, while spending billions in taxpayer subsidies. Converting less than 100% of the corn crop means less than a 2% net contribution. That’s 1 calculation.

But the other is this: Let’s ignore the BTUs that went into making ethanol and just see how much contribution to the gasoline pool it would make if we converted 100% of the corn crop into ethanol. In this case, assuming a magical process that doesn’t take any BTUs to convert corn into ethanol, could only contribute 13.4% toward our gasoline BTU requirements.

The bottom line in both cases: This “E85 everywhere” campaign is foolish, and E85 is not going to make us energy independent. Brazil is energy independent because their per capita energy usage is 1/6th of ours.

Incidentally, I have posted an expanded version of this essay to my blog:

E85: Spinning Our Wheels

I have added “Conclusions” as well as a section detailing the mathematical assumptions in greater detail.

RR

Good point, Stormy. All talk about “free market” in posts above seems to me sufficiently imprecise to render the phrase practically meaningless. As a lawyer, my toolbox consists of pages and pages and pages of laws and code and regulations—all of which: regulations—whether defined by some government or by courts (the US tax code + regulations is *feet* long). An appreciable amount of government law (legislation) merely codifies the court law (cases). Most law has direct bearing on how people operate in economic spheres. What does the phrase “free market” mean in the context of those heaps and heaps of law?

What, furthermore, does the phrase “free market” mean in an economy like that of the US where most primary innovation (ask where radar, transistors, computers, flight, laser, internet and on and on were developed) is socialized by taxpayer funding. I mean, you guys spend, what, a trillion dollars per year on military and NASA etc? That’s a heap of state-controlled innovation spending.

The phrase “free market” describes none of this. Remove law and remove socialized innovation and what would happen to your economy? What, then, is meant by free?

Thomas James, my original post has no mention of the phrase “free market.” Instead, I offer the observation that the profit motive has led to the implementation of the specific program for oil sands that Hirsch has advocated. Do you, as a lawyer, judge this observation to be accurate or inaccurate?

JDH,

In point of fact, the NRC (National Research Council of Canada) is responsible for many of the innovations that have made oil extraction possible in the tar sands, not corporations.

http://www.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/highlights/2005/0509alberta_e.html

It is true that there has lately been a synergy between the NRC and oil companies in terms of muscle to get the oil. However, the innovations that made this synergy possible arose within the NRC itself, much of it in well before there was a profit motive to exploit the sands: 1960s, 1970s, and early 1990s.

In short, if only the profit motive were responsible, we would still be looking wistfully at the tar sands.

I guess you would call this socialized innovation?

Thomas James is absolutely correct in terms source of many innovations.

The point is that simple explanations do not fit, either in terms of the “free market” or in terms of the “profit motive” as being the creator of all that is good. Once we understand this, then we can start to understand our choices and how to proceed. For example, why not a Manhatten Project to address the energy problem–government funded?

Stormy, if the current boom in Canadian oil sands was caused by actions of the NRC in the 1960’s, then why, as recently as February 2005, were both Hirsch and CAPP underestimating the magnitude of what we’ve seen happen over the last year?

To me, attributing the boom to the high price of oil is a far more satisfactory explanation of what we’ve observed during the last year.

Stormy, I didn’t know, but I’m not surprised to hear, that tarsands research was originally the domain of the NRC: yet another example, like Navy-developed fuel cells (!), of socialized innovation = big-and-necessary-risk risk sharing via tax = the country’s largest venture capital firm. JDH, I agree that greed motivates, and well. But greed-motivation is only one part of a functioning economy. And my intuition tells me that greed falls off quickly when time frames or risk dollars rise above certain thresholds beyond which other motivations dominate. It remains an open question whether greed can solve the problems of oil depletion without society entering serious economic dislocations that might, with a bit of taxpayer-venture-capital, be avoided. I guess a question I would pursue, if I had the time, is: does greed, in fact, fall off as I think it does, and if it does, what is the threshold?

JDH, re your comment about the current boom in tarsands production, could this boom be occuring as it is if NRC research had not preceded it?

Jim,

I do understand you point.

I am not denying that capital muscle has not been appliedand that the profit motive has moved into action, creating a real boom in Fort McMurrayand that that motive may provide one of the wedges we need. But we all know the oil sands is not the answeronly a stop-gap, a time gainer, if that, with some very undesirable side-effects.

What disturbs me is the bias implicit in your opening statement:

The phenomenal boom of Canada’s oil sands industry continues, despite the complete absence of any government crash program to cope with peak oil.

When many read that statement, I can hear the Aha! Governmental programs are simply not up to speed to handle the kinds of problems we face. In fact, lets just get the government out of the way so that us entrepreneurs can do our thing. I see this kind of confusion in every economic blog: the railing against governmental intervention, regulations, programsthe celebration of market forces as if they alone were responsible for all things good.

True, there was no crash program; but there was critical governmental preparation over a number of decades. Without that governmental research, there would have been absolutely nothing. Nada. The market is short-term profitability, not much else. Corporations were not willing to do the real legwork back in the 60s, 70s, and 90s. Not profitable.

It may be true as well that government may not have had the personnel or the infrastructure to do the actual work lately. (Note: I said “may.”) In that respect, I will grant you that private enterprise is doing the shoveling at a rapid and noble pace.

Government can do things with the kind of vision that corporations lack and for purposes that transcend the profit motive. Look at what the Moon program brought us. If we had depended on corporations for those inventions, we still would be waiting. Yet what wealth they brought us.

Government is the only way to collectively focus the power of a country. Usually we do this casually; sometimes we do it in times of great need. I would suggest that we are approaching one of those times.

If we deny government its proper role, as you seem to want to do in your opening sentence, then I think we are making a very big mistake. Yes, I do think a Manhatten Project is in order. And, I am willing to bet, we will see one within the next 15 years.

Thomas has an interesting list:

“(ask where radar, transistors, computers, flight, laser, internet and on and on were developed)”

I’d say that the R&D in each of those was split across government and industry. As an example, the Wright bros. beat out the establishment guy from back east, if I recall correctly, but later NASA (etc.) made their contribution.

But really I can agree that government funded basic research is a good thing, and then ask how that applies to discussions of subsidies (specifically production subsidies)?

Ideally, government monies for basic research would be spread broadly, and the result would be placed in the public domain. That is simple, clean, and allows the transition of new tech to market players with minimum of fuss, interference, and corruption.

Instead, we continue our historic and weird mix of public and private entities. I’m afraid we are corrupting the mix more than ever by converting public monies into intellectual property held by quasi-public institutions, and manipulating the take-up of those technologies by subsidy and mandate.

P.S. – If I pay my taxes, why the heck do I have to pay again when I license a hydrogen fuel invention paid for with my taxes?

Is the goal here energy innovation, or a transfer of wealth to specific lobbies?

I read the Stiglitz article and was unimpressed. China is about to adopt its 11th 5 year plan? Oh those communists, they can really run an economy, can’t they? Seem like quite a few of those 5 year plans were hazardous for the lives and livelihoods of the Chinese people.

I am not surprised that Stiglitz doesn’t think that a market economy can run on autopilot, since he is smitten with the idea of managing an economy.

According to the CIA factbook, China’s GDP per capita was $6,300, right behind Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. Not a lot to show for 10 5 year plans.

All of which is germane to the professor’s post – unplanned activities directed by price signals generated in markets can be pretty awesome. The market economy leaves the planned economy in the dust, Stiglitz’ views notwithstanding.

Stormy, at this point you are merely trolling. Your Manhattan Project fixation has grown tiresome and its’ analogous “If we can put a man on the moon, we can ……”. Funny that people in engineering never call for these kinds of projects but those with no familiary whatsoever in engineering or project management think problems can be solved by throwing money at them. Steven DenBeste covered this topic a couple of years ago. http://denbeste.nu/cd_log_entries/2004/06/AnewManhattanProject.shtml

Stormy et al.

Government intervention works in R&D when there are significant positive externalities, ie benefits that a private innovator cannot easily capture.

I would argue the best examples of this have been in biological science. There isn’t anything that the big pharma cos do that isn’t based on science ground out in universities and the research institutes of the world, over the course of decades.

The internet, the transistor, the interstate highway system are all good examples of massive externalities created by government activity. The role of DARPA in the creation and sustaining of Silicon Valley is huge and well-recognised– it’s US government research money that accounts for over half the research Stanford U does.

On carbon taxation. There is a significant, unpriced externality to the production of CO2. Basically the producer of CO2 pays no cost for the damage he or she will inflict to the ecosystem and human society by so doing.

There are two economically rational solutions which will allocate economic activity most efficiently *taking into account* its polluting nature:

1. Carbon Tax. Simple to work out. Start with $100/tonne of carbon emitted in the world and see what effect it has on global carbon production. You could actually *increase* GDP in the world by doing this *if* you rebated the tax on the *employer* contribution to national insurance (Social Security in the US).

You have to make certain assumptions to make that calculation work, but basically what you would be doing is levying a $700bn pa worlwide tax on consumption which is polluting, and then *increasing* the incentive to employ people. By a lot. The one thing we do know is that regressive taxes on employing people have a bad impact on employment, and high unemployment has a big impact on economies in terms of lost output.

2. a more ‘market’ solution which gets you to the same place. Create a marketplace for the allowable level of CO2 emissions. Scientists think we need to get down to 2 billion tonnes pa to stabilise world CO2 levels.

Let’s be optimistic and say we start with 7bn tonnes pa now, ie growth in China, India etc. will be offset by reductions in the developed world.

To emit a tonne of CO2, either as an airline, a trucking company, a WalMart, a petrol retailer, you have to *buy* that tonne of carbon on a freely traded market.

The result will be that economic activity will only take place if the marginal benefit (*including the currently unpriced negative externality of carbon emission*) of that activity is greater than the cost (including the carbon permit bought). The economy will (efficiently) allocate economic activity on that basis.

Either 1 or 2, you have a political decision. HOw much carbon emission to allow.

Economists always underestimate, in the long run, how good engineers are at changing the ways we do things– economists can show movement along the curve quite simply but are bad at shifting the effects of curves actually shifting.

Experiments with other effluent taxes (eg on water) have shown that reductions of as much as 99.5% can be achieved, and often more cheaply than expected. Similarly CFCs have almost been eliminated (although it will take 50 years for the ozone layer to fully recover).

I have no doubt if we do either 1 or 2, that carbon emissions in developed countries will fall by 40% very quickly. Getting from there to the sort of 70-80% reductions that are necessary, to stabilise the global climate (or rather to make the changes no worse than already forecast) will be harder.

The evidence is mounting up we need to make this shift quickly. Perhaps in no more than 30 years. Whether we choose 1, or 2 (which is in place in Europe in a limited way), we have to start sooner rather than later.

The problem of global CO2 emission and climate change is predominantly an economic one. We have to spend money now, and change our behaviour now, to avoid the *potential* of a really serious disaster (down to threatening life on earth) in 30-40 years time. there is nothing in trying to do that which is impossible in engineering terms with current technology.

Humans are bad at those sorts of tradeoff. But the time has come.

ON the vexed question of the Third World, and China and India, getting a ‘free ride’ eg out of Kyoto.

The US is 1/4 tonnes of carbon emitted. Canada is another 2.5%, so is Australia. Europe is about another 25%. Japan another 10-15%.

So the developed world is more or less 3/4 of the CO2 currently being emitted. And of the historic CO2 (CO2 sits in the atmosphere for 20-30 years, causing change) we are more like 90%.

We *have* to move now, in our own long term interest. Once we have started down that path, *then* we can use moral suasion and threats of trade restriction, to get China, India and other developing countries into line.

But morally, and to create political legitimacy for what we are trying to do, and in our own economic self interest, we in the developed world must move *first*.

The clock is ticking. It’s going to take 30-40 years to stabilise the world’s CO2 level (at least) and world climate will keep changing until the 22nd century.

My best is we are in the last 50 years of the current civilisation. We can move on to a new, low emission civilisation (by which time, technologies like Solar Power Satellites or nuclear fusion may have changed the picture entirely) or we can drown in our own CO2.

Rich

The Chinese economy is showing the fastest growth ever recorded for a large economy. Faster than Japan in the magic period 1953-late 1960s. Faster even than Taiwan or S Korea managed in their ‘take offs’.

GDP is doubling there *every 7 years*. And the US dollar calculations of it are at least a 40% understatement, as the Renimbi is purposely undervalued. China has gone from being a very poor country, to a middle income country, in 28 years.

Stiglitz’s point is that it is hard to understand this in conventional market economic terms. They don’t even have legal private property yet!

What is going on in China is remarkable, unique in economic history (check the price of copper!), and in uncharted waters. It doesn’t really confirm the prejudices of ‘free market’ thinkers, nor of ‘planned growth’ ones. It is some strange hybrid of the two.

Valuethinker, can you expand on “there are significant positive externalities, ie benefits that a private innovator cannot easily capture”? Government funding (ie, socialized risk sharing) seems to me a critical component of the economy. I’ve also heard little conversation on the subject, leading me often to question the basis for many a discussion on things economic. Pharma, as you mention, is yet another huge example of socialized risk spreading. The list also includes large items like nuclear, which probably will factor significantly in any future economy. Seems to me the only company large enough to handle these big and high-risk projects is GovCo.

To catch a glimpse of the importance of GovCo venture funding, remove from the economy: pharma, transistors, computers, the internet, laser, etc, etc, then ask what remains? What remains would be unrecognizably different, so different, in fact, that one might begin to view that arena we call the free market, the place where greed operates, as to some appreciable degree a marketing arm of GovCo. GovCo creates the transistor; we get car stereos. I mean, Bill Gates, who in our lowly realm might be called King Marketer, has a total net worth that calculates as what fraction of a percent of GovCo yearly innovation spending (military+NASA+university+ … )?

I don’t mean to belabour this point (“our” spelling, he’s Canadian!), but JDH began by saying, to effect, look how greed is solving the problem of peak oil. That it surely is stepwise doing, to some degree at least, but for my part I can’t help but look at the arena in which greed operates, and to ask what forces defined that arena in what interests etc? Government tarsand goes far beyond NRC + ARC funding to include *huge* tax-related expenditures. I sat on a case in the mid-1990s in which Gulf Canada claimed a tax deduction for early tarsand expenditures. The claimed deduction constituted a small part of the total tax relief Gulf received. The amount of tax riding on this deduction? $800,000,000. One case. The Government of course lost the case—wrote the cheque—probably because at some deep level society realises that innovation in such realms as energy technology is vitally important.

Realising I am not particularly clear on one point above.

Shifting along a current production curve where output = f(capital, labour, physical inputs, carbon) is relatively easy to model.

Producing a tonne of steel costs ‘x’ of carbon.

What is much harder to model is where there is a step change in the efficiency of a process eg where someone invents a new way of making steel that produces half as much carbon (eg the switch from open hearth to basic oxygen steelmaking and again to electric arc). that is a shift in production function, not a movement along a curve.

Or, even more complex to model, is a switch from using steel to another material which produces less atmospheric CO2.

I thought it would be interesting to look at the following –greedy– ethanol CBOT June chart:

http://www.cbot.com/cbot/pub/page/0,,1754+chart,00.html?symb=AX&month=M&year=06&period=D&varminutes=&study=&study0=&study1=&study2=&study3=&bartype=BAR&bardensity=LOW

where a dizzying $2.80 to $3.42 or 22 % price increase transpired in the past 2 weeks.

So, one AXM06 contract with an initial margin requirement of $2,700 would have rendered $17,980 by today; or a per contract performance of 6.66 x in 2 weeks enough to even awake Mao Tse Tung.

I posted a while back that a 3,000x increase in production would be required for a US mandated E10 or a 10% replacement of gasoline by ethanol.

In any case, Im wondering how far up ethanols price could rise, considering tax incentives and what I would call the war premium, or the Prius premium paid to exert ourselves from the middle east oil dependency?

For an E10 with a $5.00 ethanol and $2.50 gasoline price, the combined price would be $2.75, a $0.25 difference I think people would be willing to pay an extra 10% for an E10 blend any ideas?

I guess Im too greedy

Thomas James

Think of technological change in 2 parts:

1. the pure ‘science’ to achieve something that we don’t know how to do

2. the capital expenditure to build a plant (fibre optic line, internet server etc.) that actually makes that a real product or service

Business is bad at 1. There were institutions like Bell Labs or Xerox Parc which did produce great innovations (the mouse, windowing, etc.). However many of these have been closed: even when great innovations were produced, it was hard for the companies to exploit the markets they created.

Many of the really big scientific breakthroughs take decades, if not centuries. By the time nuclear fusion is practicable, we will have been working on it for nearly 100 years (2050 at the latest estimates).

Even when we get to a self sustaining nuclear reaction, controlled, in a fusion test reactor, then we have to turn that into a power plant prototype, proving that the process can be scaled up.

*then* the world’s companies will jump in and build commercial fusion reactors. But they won’t do so until the market is within their forecast horizon (typically 10-15 years for really big capital projects).

When the laser was invented in the 1950s, no one imagined every telephone call in the world, let alone the Internet (which didn’t exist at that time) would go down a fibre optic powered by a laser.

There are lots of other examples. Industry finds it much easier to hire a new geophysicist, say, from a competitor than to train one from scratch. Someone has to create a university system that trains geophysicists for all companies to hire them.

No university system in the world is entirely private. The great American private universities, like Stanford, derive large fractions of their research income from the government.

On stage 2, there is a much weaker case for governmetn involvement *however* in the case of the tar sands, someone had to build the test bed plants, refine the processes, keep learning all the difficult stuff about making oil from sand.

A few oil companies (Shell) stuck with it. But they could do that because Shell is essentially bid proof, and so could afford to lose money for decades whilst creating new technology. And Shell is the company that invented Long Range Planning (see Peter Schwarz The Art and Science of the Long View– he worked for Shell). Most oil companies are too busy being taken over to worry about 40 year scenarios for the supply and demand for oil — 40 years is the right time horizon, the first Tar Sands work was, AFAIK, in the late 60s.

Now that there is a clear market for tar sands oil, at a high enough price to justify the billions of dollars invested, and the technology of getting this stuff out of the ground and out of the sand is well proven, private companies will invest and reap the gains.

It has been estimated that the single highest return thing the US government has ever done in science is to invest in high energy physics. Those colliders cost billions, and they have no short term or visible practical applications. Yet they underpin the US defence effort, and the entire past and future of electronics.

I would wager the other one is the research which is now leading to the genetic revolution. There are now multi billion dollar biotech companies (Amgen) but none of that industry would exist without a huge infrastructure of government subsidised universities, government funded scientists, and really fundamental work about the nature of DNA and the human genome.

I would wager we are in the same position with solar cells. If the US government announced that there would be say 3 million solar homes in 10 years (or about 1/7th of those built in that time), the market would respond to that. Solar cell prices are already halving every 10 years, I think the speed of technological change would be accelerated– the private sector would respond to the created demand.

Thomas James

On nuclear power (civilian) it is important to understand the industry would not exist without substantial government subsidy.

Besides the (unsolved) waste problem, which governments will have to solve (the UK cleanup bill is now estimated to be 70bn) there is also the insurance policy governments grant to operating nuclear reactors. No insurer can write a policy for the hundreds of billions that potential liability represents, in the case of another Chernobyl in a western country, say.

Further all of the technology in a civilian nuclear reactor was originally funded by government. Be it Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd (for CANDU) or the US department of Energy in the US (going back to the Manhattan Project).

Lastly, nuclear power has never made sense in terms of pricing, unless the electricity market is government regulated. The volatility of electric pricing is too great without regulation– the rational generator would use gas and other fossil fuels.

For this reason, in the UK’s deregulated electricity market, the all nuclear power generator, British Energy, went bust and had to be rescued. Ontario Hydro (as was) is in a similar pickle.

Throw in a carbon tax or permits system (more government regulation) and nuclear power may well make sense. But in a ‘free’ market where there is no charge for the carbon emission externality (a negative externality this time), nuclear power has never made sense economically.

Valuethinker, thanks for your posts. I find what you say very informative and I instinctively agree with your observations. I particularly like your phrase “forecast horizon,” as it expresses what I was above trying to say in suggesting greed operates only in a confined sphere beyond which it simply refuses to go because risk or required capital or time before return are too high. At least some (possibly most) component parts of the overall task of generating future technologies to replace oil—or more minimally to mitigate the effects of peak—look to me to reside outside business’ forecast horizon. As to the utility of government policy, one might ask what mother or father would risk sacrificing his family to avoid a little inefficiency? Surely not the reasonable self-interested economic person?

ValueThinker and James,

Excellent exchange. Much to consider.

Serious debate on these issues is really needed. How a civilization prospers and survives is a complex matter.

I was going to add that more and more government R&D is being diverted from universities to corporations.

Corporations know how a fledging idea can flourish in a university and potentially become serious economic rival; corporations wish to forestall this kind of developmentquite naturally so, I must add. Unfortunately, they do not necessarily provide the kind of culture or vision required to produce those ideas.

Stormy

If a business cannot appropriate the value of an idea, it is in its interest either not to pursue it, or to suppress it.

Thomas James

A corporation suffers from a couple of disabilities. One is the short time horizon in career of senior executives. Hard to plan for 30 years ahead when the average tenure is less than 5 years.

The other factor for a company is that there is plenty of evidence that the stockmarket is too volatile in the short term. To the extent that a company’s managers are sensitive to the stock price, either due to stock options or fear of takeover, there is an incentive to respond to the volatility of the market, which will alter decision making horizons.

A third factor for a company is that if it cannot appropriate the gains of a new technology, it will either ignore it as an unprofitable investment, or seek to suppress it as a potential competitor.

A fourth problem for a company is human capital. Companies will underprovide human capital in terms of training and education, because in most cases employees can walk for a higher offer. Training lots of people doesn’t make sense if the next time there is a boom in the industry, they walk.

This is what is happening to resource industries now. For 15 years they have not trained or hired enough engineers, geologists, geophysicists etc. So now there is a boom, and no one to meet it. The average age of an industry geologist is over 50, apparently.

Valuethinker, can you honestly look at the U.S. government’s policy on Social Security and Medicare and try to convince us that the government is inherently more far-sighted than private corporations?

I am, for the record, an ardent supporter of government spending on basic research. I agree completely with the example you gave earlier about genetic research.

Jim,

I have a question. It may seem a bit weird, but I do not know how to think it through. And I am not sure I can state the question clearly enough.

Simply put: Can a market driven civilization be at zero growth indefinitely?

JDH

Social Security has been extraordinarily far sighted.

Roger Lowenstein has documented that the founders of SS actually predicted the increase in human longevity to within 2 years. An extraordinary feat (or a very lucky guess) over 65 years.

The programme is now within 7% of meeting its obligations to 2042. 7%, on a programme 36 years into the future! On conservative estimates. An increase in taxes of 1.3% of GDP (ie a less than 1/4 of the US Federal Deficit) will correct those problems.

It has had one ‘mid course’ correction ie that under Ronald Reagan. A big correction, to be sure.

On any basis, that is a pretty successful programme.

I work in the private sector in computers. I would say the *average* cost overrurn in the private sector is 50-100% on software projects. At least 1/4 projects I work on is abandoned, without ever working.

All those big ‘extraordinary items’ on the Profit and Loss accounts of big firms are precisely stuff like that: big software projects that fail, or acquisitions that don’t pan out. There have been years when the writeoffs on the SP500 have almost exceeded earnings on the SP500. *that* is how good a forecaster the private sector is!

As to Medicare, I have seen analysis that shows that Medicare is no less cost efficient than private plans. And in any case, the private sector wouldn’t insure a lot of Medicare patients (too old, too sick).

I agree costs are rising too fast in the long run, but they are not rising faster than for private plans (apples for apples comparison difficult, as above).

A better example of what we are talking about would be the Clean Air Act, which no private entity could ever have created or enforced, or the ban on DDT or CFCs (ditto). All of which have paid huge dividends for society: the externality problem again.

ValueThinker,

I can second your comments re software development, having worked extensively in that field. (Most of my immediate family are in IT, from advanced switches VoIP) to networking to software development director at one of the Fortune 500.)

In all fairness to Jim’s position, I would add that software development in government, from state to national, is nothing to write home about either.

Regulation law changes and fickled reporting demands put heavy strains on those at the bottom, especially when the software is not up to speed or is years late in coming. Bureaucrats sometimes think that putting a computer on a desk is all that is needed.

In this regard, both government and business are wasteful and inefficient, albeit in differing ways.

I agree with many of the points made here.

I am a research physicist at a major US university;

and unfortunately now involuntarily unemployed as my funding has run out and I have not been able to get funding for at least 2 years despite substantial continuous efforts.

Some facts and observations from the inside:

It takes about 20-30 years to go from initial scientific discovery to commercially successful product. Private companies, either established or new via venture capital, now will typically fund the last 1.5 to 4 years, approximately. The high end being on the biological sciences where clinical trials and regulatory issues lengthen time, but patent protection gives a strong monopoly unlike physical “high tech” inventions.

Perhaps in the past (big Bell Labs, IBM, etc) they might fund a few up to 5-10 years but the large research private institutions are no more.

In contrast to what was prevoiusly said, a larger fraction of research is not being done in companies; quite the reverse, the private companies are declining in their longer term research. Note that some numbers are quite substantially misleading because operational upgrading is being characterized as ‘research’ for taxation benefits when it is nothing like research in the fundamental sense.

The number of scientists attempting to get US government funding for basic research has increased substantially but the proportion which is successful is declining as rapidly. Funding ratios in programs are now about 5% or less at National Science Foundation (number of successful applications to applications). Consider that successful applications by scientists already requires significant prior scientific success and that just preparing the applications takes months and is far more difficult than successful scientific publication.

Another anecdotal but significant datum. Many immigrant or long-term visiting scientists who thought they had futures in the US are quickly returning or seeking employment back in their home countries. Even just 10 years ago the US had significantly more opportunities which brought the scientists over, as has been the situation since 1945 really. A senior person I know here in the US is looking for jobs back in Macedonia of all places. Other EU people are finding long-term employment and research funding better in the EU and are going back. Only the Russians are staying.

The tide is turning in a way that I’ve never seen before.

Another fact is that the types of problems which are optimally solved by the venture capital free-wheeling type of US technological capital, e.g. chip design, software, internet services, may be fundamentally distinct from those necessary in the future and today: globally large scale environmental and energy engineering programs.

No startup has successfully made far superior cars and marketed them on a large scale, nor will one even remotely be able to design produce and commercialize a better nuclear reactor.

These types of projects intrinsically need large scale organized deployment of long term capital with scientifically oriented managers, with government cooperation.

I have the feeling that the Japanese will do quite well, now with Chinese companies providing the brawn and increasingly the engineering support.

The US seems more doomed to be trying to sell insurance to them, or wasting money on more “security” spending which has a negligible economic rate of return.

Finally, “Peak Oil” is an geophysical fact. The only question is a little debate on where we are, whether it’s 45% or if we’re more at 50-55% global total depletion.

Dr. C,

Sorry to hear the funding ran out – hope something else turns up for you soon.

The world is full of irony, is it not? Shell may have invented long, long range planning, but it was Shell who employed Dr. M.K. Hubbert and eventually ran him off for coming up with a heretical if correct perspective on long, long range oil production volumes in the U.S.

And back when Bell Labs was the archetype of a basic science R&D program, they invented the transistor but never did anything commercial with it. And of course IBM developed RISC chip set computing and relational databases but were quite a bit on the late side commercializing those innovations. The list goes on and on.

Last, on Social Security I have to disagree with Valuethinker. Social Security is an excellent example of the something-for-nothing myopia that makes for really awful government programs.

The first and most egregious problem with Social Security is the accounting. The official accounting is done on a “cash” basis rather than an informative actuarial accrual basis. If you won’t keep score accurately, you can’t do anything honestly or objectively.

Secondly, Social Security has had several financial crises over the years that have required substantial tax hikes far above what the planners anticipated. And of course the Social Security taxes are quite regressive in nature.

Third, it’s not only longevity (which the founders of SS may or may not have accurately anticipated) that’s causing the solvency problems, it’s the decline in the fertility rate that’s going to produce an impossible-to-sustain increase in what demographers call the dependency ratio.

Last, it’s pretty likely that the structure of Social Security reduces private savings, which is something the U.S. is systematically short of . . . . . see this good CBO review for details:

http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=731&sequence=0#pt6

Regarding some high tech IT hardware development:

The cases I know personally have involved doing the original and initial work here in the states, then sending the clean-up and completion elsewhere–where the engineers are cheaper. Eventually, the talent pool here will disappear.

DrChaos is watching first hand that talent pool recede. We seem more interested in making a quick buck through high finance than solving some of the pressing scientific problems.

Re Social Security: For those at the low end of the wage scale, it is often all they have. I would certainly not turn it over the the likes of any of the major investment firms, whose questionable promote, buy and sell strategy quickly eats up profits, leaving the uniformed with little.

The argument that it is regressive may be a bit disingenuous, considering that it often is all that some people have.

As paternalistic as it may sound, the vast majority of people have neither the education nor the will “to save” that money, especially if they are already stretched. It will be just more one dollar to purchase goods or services –to fatten already fat wallets.

As far as the “SS” crises are concerned, we can easily point to the pension fiascos that some of our major corporations have created through underfunding or outright fraud.

Whatever fixes SS needs are relatively easy to make. A shortfall some decades out is not as much a cause for alarm as some of the other issues we face.

I find myself somewhat suspicious of the motives of the finance community to put that money into circulation.

Stormy

I wasn’t arguing government was any great shakes at long range projects, just that the much vaunted ‘success’ of the private sector wasn’t particularly greater in many cases (usually with large projects with large uncertainties).

Anarchus

Look again at SS. The ‘crises’ were solved. Demographics will not destroy SS. Rather, the % of GDP consumed by the programme will go from 4.5% now to 6.5% at the peak, as the Baby Boom peaks in the retirement years. This is entirely sustainable, and the existing system comes within 7% of meeting its financial requirements on current projections (that is 93% of all the money it is going to pay out). The source for that is the SS Administration itself, which works to deliberately conservative guidelines.

For a developed country, US demographics are looking pretty robust. Mostly because US Hispanic immigrants have a high fertility rate (TFR of 3 children per woman in a lifetime) and US non-Hispanic whites have a not bad one (1.8, or about the UK level, v. 1.3 in Italy and Spain).

If there is a crisis it will be in healthcare spending. This will be a Medicare problem simply because the private system doesn’t extend to the post 65 age group. But no one could devise a privatised system which would.

On the savings ratio and SS, I think it’s bollocks. Feldstein has walked around for over 2 decades claiming half of SS is lost in reduced private pension savings, but there is no evidence for this.

There is no evidence cross-sectionally, looking at the US v. other countries (Italy has one of the highest private savings ratios in the Western world and also the most generous pension system).

There is no evidence looking at changes in the US savings rate, v. changes in the SS system. The US savings rate has fallen below 0 in the last 8 years but there have been no significant changes in the SS system.

The reality is that 90% of savings (non housing) are held by 10%of Americans. They are not sensitive to changes in the SS system, as that is not their primary form of retirement income.

For Americans for whom SS was a primary form of retirement income, they don’t have savings anyways. These are not people who invest in the stock market (in a significant way).

The sky is not falling under the US SS system. Anything but. The opposition to it is entirely ideological. Karl Rove has admitted as much. If he can kill SS, he can kill one of the most popular and successful government programmes, and critically weaken the Democratic Party and the New Deal, forever.

*this* is why the Republicans keep coming up with schemes that will weaken the financial stability of SS, increase the current US government deficity, enrich the asset management industry.

As Warren Buffet said ‘SS isn’t broken, so don’t fix it’.

Dr. Chaos

Your thoughts depress me although they do not surprise me.

One of the consequences of the Club for Growth/ low taxes under any circumstances ideology is that government cuts what is politically least sensitive, first. That is inevitably public universities and science.

Couple that with almost a national policy to ignore or denigrate inconvenient science (see Christopher Mooney ‘The Republican War on Science’) be it on global climate change, genetics, etc.

I also agree with you that long term research, and many megaprojects, cannot be financed solely by private capital. This is an area where I have done a lot of work–I know what venture capitalists will and won’t finance. They are surprisingly risk averse.

In the UK we pay our research scientists so little they tend to go into finance or other areas. Lots of PHD physics modelling options and swaps in the City (Wall Street). Others go and work at the likes of McKinsey, which love to hire very smart people, trained by someone else!

Europe I think the wheels are coming off the trolley because of the fiscal pressures on governments. At least we are proceeding with ITER (the next large fusion project).

I am having dinner with a friend who is leaving the academe (tenure track job in liberal arts at an elite east coast liberal arts college) to attend law school. He is just fed up, and at 40 is beginning his career again.

My best thoughts at trying to find a new role. Are there any desirable alternatives?

(remove ‘at’ from email address to reply by email)

J.

Stormy, a while back you asked whether a market economy could be consistent with an absence of growth. I see absolutely no reason why not. Indeed, when we teach economic growth models, most of us start with the base case of an economy with no growth because that is an easier one to understand.

A zero-growth economy would of course allocate its productive resources differently than a growing economy, so many people would end up doing different kinds of work than they currently do. If the transition occurred very suddenly, no doubt it would cause significant economic disruption.

Jim,

Thanks. You have always been helpful.

We may be forced to create business models based on zero growth. I am not sure how greed will work in them.

To understand the growing mistrust of big business, I suggest the following link:

http://www.alternet.org/story/36718/

Read some of the comments to the piece as well. Enron is not a “one-of-a-kind” who chose an inappropriate accounting model. When you read some of the posts, including those from people in local government, you can start to understand how large corporations easily abuse power.

At some point, the business model will have to change to include real civic responsibility; that may mean that greed as the driving force will have to be replaced with something else.

Anyway, you may find the link interesting. It does express a number of important points for consideration.

Carnival of Capitalists – Downunder Edition

Role up! Role Up! to this week’s Carnival of the Capitalists (being hosted from Sydney, Australia). I am your host, Leah Maclean, and I hope that you enjoy the 42 submissions to this week’s carnival. Take a moment to not

I think the US is still an adolescent society and the ideology disparaging govt and our myths of individualism (and libertarianism)- Bush’s cowboy pose – these are characteristic of the bad judgement of adolescence. They are myths of immaturity. Some people don’t grow up because they want to, they need to be hit over the head by reality. I think Iraq did that to the Neo-cons. I think global warming and peak oil and avian flu may be another blow to the anti-government ideologues.

Sometimes I wonder how many millions will die because Americans don’t want to grow up.

Growth is but a stage in life that serves specific purposes. Animals (not to mention life on planets, and stars, and whatnot) stop growing once those purposes are met. I assume economies are no different, and that growth is an early-stage development that tends toward stable, zero-growth operating. From just a numbers perspective, unless you change as that which grows in the concept of growth, the earth simply cannot sustain continued growth. Extrapolate 1000 (let alone 1 million) years of even 4% growth.

One thing that will not stop growing is knowledge, the accumulation of which drives effciency growth, among other things.