Is Saudi Arabia part of the reason for oil’s new price highs?

Petrologistics, a Swiss firm that tries to count the physical quantities of oil produced and shipped by tankers, has been reporting that Saudi Arabia produced under 9.1 million barrels per day during April, May, and June. The same numbers have also been reported in recent press statements from the Saudis [1], [2], and would represent a 400,000 barrel a day cut from what Saudi Arabia had been producing for most of 2005.

The interesting question is what this means. A recent article from Reuters declared that these production cutbacks prove that supply and demand are irrelevant for the price of oil:

Oil power Saudi Arabia has offered the most compelling proof yet that record high prices are divorced from the realities of supply and demand. The world’s biggest crude exporter dared to make a huge cut in its production through the second quarter but growing demand for oil was still satisfied….

“There is absolutely no relationship between price and supply and demand,” Saudi Oil Minister Ali Al-Naimi noted. He told pan-Arab newspaper Al Hayat in early June that crude oil was worth no more than $50 a barrel based on fundamentals. He has repeatedly said the oil price is determined by the multi-billion dollar market that brings together oil companies, traders, investment and hedge funds.

“The reason for the cutback is simple. People are not asking for oil,” said a senior OPEC delegate. Heavy refinery maintenance, especially in Asia, dampened demand and tanks continued to fill.

There is nothing mystical or mysterious about the process whereby hedge fund speculation leads to an increase in the price of oil. If more people are trying to buy rather than sell oil futures contracts, the price of these contracts is bid up. If the current spot price of oil did not go up with it, that would create an arbitrage opportunity for anybody to put more oil into storage today which they can then sell forward risk-free through a futures contract. The oil put into storage for this purpose is an added component of the demand for the liquid, in addition to that coming from refineries intending to use it in the present period. This is the mechanism by which increased speculation in “paper” oil translates directly into an added component of the demand for physical liquid barrels.

It should be perfectly clear that while speculation adds to the demand for oil and thereby can drive the price up, if Saudi Arabia or anybody else produces more oil, that means that more oil is available on the selling side of these contracts, and the lower would be the resulting equilibrium price. If the Saudis do not find buyers for the particular grades of oil they are producing, they could either discount the price of that oil or lower production. Which they do is a choice the Saudis make, not the mysterious outcome of hedge fund speculation. It may well be that the Saudis are experiencing lower demand, but if so, it is their cutbacks in production that are causing the price to rise rather than fall in such a situation.

One can speculate on the nature of that reduced demand for Saudi oil. Petrologistics offers these details:

Oil power Saudi Arabia has cut exports to Asia by over half a million barrels a day since March to match lower demand from refiners during their springtime overhauls, tanker tracker Petrologistics said on Wednesday.

That has been the case during the second quarter with Saudi Arabia shipping 220,000 bpd less crude to Asia in May than April, said Conrad Gerber, the head of Petrologistics. Exports in April were already 350,000 bpd less than March, he said.

Buyers in the west took 180,000 bpd more Saudi crude in May than April, compensating in part for the fall in the flow to Asia. The flow to western buyers in April was 150,000 bpd less than March, Petrologistics said.

It is interesting to read that story side-by-side with Bloomberg’s report that Japanese refiners plan to buy most of the 250,000 barrels per day expected to start flowing soon from Russia’s Sakhalin-1 project. It certainly makes sense for Japan to buy less oil from Saudi Arabia and more from Russia, from the perspectives of transportation logistics (the Russian port is 10 times closer) and diversification of supply.

One also wonders whether the “springtime overhauls from Asian refineries” is related to this story from Reuters:

China will extend a 50,000 barrel per day (bpd) cut in Saudi crude oil imports into July and August after some refiners struggled to cope with new higher-sulphur supplies, industry officials said.

China contracted to buy 500,000 bpd of Saudi crude in 2006, but cut that back by 10 percent in the second quarter after refiners ill-equipped to handle the kingdom’s mainly heavy-sour oil were forced to slow production after running the grades, the officials said.

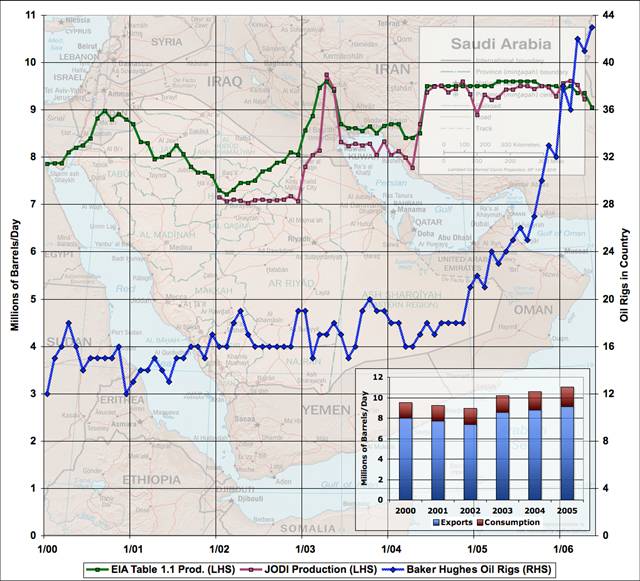

It’s also interesting to note that these drops in Saudi production have coincided with a huge increase in Saudi drilling efforts. The graph below, taken from the Oil Drum, shows estimates of Saudi production from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (green line) and the Joint Oil Data Initiative (purple) along with the number of oil rigs in operation (blue). The Saudi explanation is that they are aggressively trying to develop more excess capacity, though, if that’s their intention, why not use existing capacity to prevent the price from rising to $75? One can’t help but wonder that, when Saudi production peaks, the graphs and official statements might be quite similar to what we’re seeing right here. That possibility is conceivably one of the factors driving those investment funds to keep on buying oil futures.

More questions than answers at this point. But definitely a story worth following closely.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

Saudi Arabia,

peak oil

“If more people are trying to buy rather than sell oil futures contracts, the price of these contracts is bid up. If the current spot price of oil did not go up with it, that would create an arbitrage opportunity for anybody to put more oil into storage today which they can then sell forward risk-free through a futures contract.”

Suppose there’s no more storage available (as suggested by the fact that inventories have been at historically high levels). What happens then?

Hal, if there is zero storage capacity in above-ground bins, there’s a profit opportunity for anybody involved in the process to slow down production and delivery, keeping oil in tankers or in the ground, reducing current liquid supply (not to mention build more bins). Fundamental issues are still the same.

Just can’t wait for that moment when the hedge funds begin to run their game in reverse. Do I hear anybody predicting $37?

What a game. First induce excess storage as mentioned above and then walk the cat back. I wonder if someone over at The Carlyle Group will ring the bell at the inflection point. Maybe even George Herbert Walker Bush in one of his unguarded moments. Nah.

Anyway, $37. That’s my bet.

BTW…I would be interested in learning what other readers/commenters here (including JDH) conclude regarding the ability of the hedge funds to walk the (WTIC) cat back into the $30s (or below).

Re the “profit opportunity for anybody involved in the process to slow down production and delivery”: that’s what Saudi Arabia is doing, right? So it all makes sense? The production slowdown we see is not due to an inability to produce, but rather an opportunity by suppliers to make profits from the hedge fund speculators?

Flat or slightly declining level of production with sharply increased rig count hmmmmmmmm

Sounds like someone is running hard just to stay in place.

$37? Only in your dreams.

Though nonresponsive to the current Saudi post, I think the topic real-cost-of-alternatives is one that, if not touched upon already, is worth touching on in the future, as reported in this article:

Oil Sand Cost Increases.

Pundits frequently tout the price point at which alternatives become viable. Physicists counter that energy returned on energy invested must be taken into account. When oil is $35/barrel, the pundits tell us that $50 is a price point for some alternative. When oil is $75, the price point for that alternative does not necessarily remain at $50. If energy is the objective of the development effort, then EROEI seems paramount.

Price is not the only issue here.

Storage is also used to mitigate the possibility of supply disruption. The potential costs to transportation, commerce and industry from an oil shortage are a real driving force. The price will drop only when supplies seem more secure rather than on a speculators whim.

TR – it is even more complex than just energy returned over energy invested… one has to look at the UTILITY of the energy sources & products and not just the yield.

For example I might be willing to invest a million BTUs of energy into a process to only get back a half million BTUs… While this might sound like a ‘net loser’ it might still be worth doing IF the million BTUs invested are very difficult to use but the half million produced are VERY easy to use.

An example might be building a coal powered syn fuels plant where X BTUs of less useful coal goes in as the ‘investment’ and Y BTUs of syn fuels comes out. By the very nature of the chemistry the yield X:Y will have to be less than 1:1… it is more like 2:1 with for a syn fuels plant… quite a lot of the coal feedstock is consumed in the process – ends up being exhausted as CO2 before a drop is put into a car.

Similar with oil extraction. Say we want to continue pumping oil out of old inefficient wells. It appears to be a loser if the energy to run the pump exceeds the energy of the oil coming out. And it is a loser IF the pump runs on gasoline or diesel and more is consumed to run the well than crude it produces that can be converted back into gasoline or diesel.

But suppose the pump is powered by solar panels or a windmill & NOT by a gas powered engine. And suppose the well is so remote that the solar or wind power at the wellhead can’t easily be used for something else. In such a situation a negative OVERALL energy yield is still a winner if the value of the oil obtained is sufficiently high to cover the cost of the solar or wind powered pumps.

It is never just about the net yield… it is also about the conversions & utility of both the energy source & resultant products.

JDH:

You say that stocks are high, but this seems to be something of a local anomaly in the US, and partly an artefact of storage capacity not keeping up with growth in volumes. On a global basis, and looking at days of forward supply rather than physical volumes, commercial stocks are right in the middle of the historical range.

See this graph from the most recent EIA Short Term Energy Outlook for example:

http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/steo/pub/gifs/Slide24.gif

Also one nitpick: the purple line in the Saudi graph is from the Joint Oil Data Initiative:

http://www.jodidata.org/

Dryfly: I understand. E.g. when stranded natural gas used to extract oil from tar sands.

The key issue is the increasing percentage of world supply coming from heavy sour crude and the corresponding reduction in light sweet crude. In the Saturday July 8 Financial Times there is an article on page 1 stating that last week Saudi Arabia cut the price of its heavy oil and raised the price of its light oil.These price differentials can only increase as light sweet crude continues to be a smaller and smaller percentage of world supply. The reference to $37 oil is not out of the question. But what grade. In Canada in Q1 2006 for a variety of reasons (which have since corrected to some extent) the price differential for heavy oil was around $32 per barrel at its high. So yes heavy crude was only fetching around $40 for a brief time. In addition, and as noted, the Saudis say that $50 is the appropriate price for crude. I assume this is a reference to the OPEC basket. WTI generally has traded at a 15% premium to the OPEC basket. I suggest that the Saudis and OPEC would quickly cut prouction to defend this price point. Also, the margin of spare capacity of “useable” crude available on a sustained basis in politically secure areas will continue to impact the price of crude. At present this buffer is simply not there.

Thanks, Stuart, I’ve corrected the error.

ESB, I don’t see how this “walk the cat back down” theory could work. Somebody bought a July futures contract last January for $66, and they’re feeling pretty good right now. But if the price rise from then to now has been entirely driven by speculation, it must be due to an even bigger volume of people who last week purchased a Feb 07 contract for $78. Suppose the unwinding process were to begin now. If there is no new pressure from new buyers of futures contracts, the price would have to go back down below $66. So the people who bought last week would lose more than the people who bought in January, and there would be more of them.

For this reason, I’ve argued that speculators can only profit when the fundamentals turn out in their favor, that is, if those who purchased the $66 July contract last January were correct in their assessment that a price above $66 today was warranted on the basis of fundamentals rather than on the basis of the assumption that there is going to be an even bigger group of investors willing to pump even more money into the markets every 6 months.

If it is true that nonfundamentals speculation has contributed to the current run-up, then those nonfundamentals speculators are eventually going to get slaughtered.

On the other hand, true fundamentals can include the chance of something that turns out not to materialize, for example, the risk of a loss of Iranian production, or the risk that the Saudis are not capable of further big production increases. I have no doubt that such risks are making a contribution to the current price of oil, and that the mechanism whereby these risks show up in the price is the speculation we are discussing here.

Thanks JDH. I think it’s possible that the Saudis could be slowing down on production, just to enjoy current prices a little longer. I think it’s also possible they they could be drilling, testing, and capping a bunch of wells to expand (and know!) their spare capacity.

Beyond that, it’s the same tea-leaf reading as always, without knowing their (true) reserves we have to guess their motivation and strategy. But for what it’s worth I think motivations to underproduce are more plausible than motivations to overproduce.

There is no way that the price of tulip bulbs will come down….

Bruce, here are some thoughts about those tulips.

I think the futures market is rigged.

Prices are set on the margin so you don’t have to buy every barrel – just a little more – even in the oil market.

Super Saks Bank organizes with Super Cities Bank and litle bank c,d,e etc and their big money buddies at the hedge funds to drive the price of (enter commodity name here) oil.

Meanwhile the physical market provides X daily underlying demand that is relatively inelastic in the short run. The “speculators” (mob) have committed 300 times X for the project.

Monday – buy X + delta – shock the market

Sell delta/2 Monday afternoon buy delta at days end – hold

Tuesday – X buys mechanically – somebody shorts ( a small timer not in on the fix)- buy another delta – force them to cover

etc. etc. etc. until market is swollen with 300 X or whatever. As long as you can drive the price up and sell half your position to X at the higher price.

Then agree to sell. Everybody starts selling.

Once a person gets over the idea that the futures market is not competitive but the home of financial organized crime – the rest makes sense.

The industry ain’t dumb. Their either in on it from the start or they see what’s going on and jump in with both feet.

It looks to me that the fix is not at the well head but the refineries. Cartels can always produce more – they choose not too. Max profits by selling less for more. BP just got busted for manipulating the propane market.

Eventually the inflation caused by the merchant class will put the economy into recession and oil will be below $ 50.

Thanks for the post.

Yin, I’m not following the “etc., etc., etc.” part of this strategy. Actually, I’m not getting past day one. Are you somehow assuming that you sell the delta/2 on day 1 for a higher price than you pay for the new delta at the end of day 1? Why would that be? If you sell the delta/2 for the same price you pay for the delta, what does the sale accomplish other than helping your broker feed his family?

What is the net long position of your speculators after day n of following this strategy? The net long position is always increasing until it reaches 300X, and then they sell out the entire position? And who buys the 300X when the speculators do sell all 300X?

The only way to make a profit by buying an oil futures contract is to sell it to somebody else who pays more for it than you did. It is not clear to me from your plan who that somebody else is, and why they want to pay more for the contract than you did. If all you ever do is buy it back yourself and then buy even more new contracts besides, you’re not going to come out ahead.

I have been inclined to see the increase in commodities prices generally, and oil prices in particular as a money bubble. If so, the price trends should be broken by monetary tightening, which the Federal Reserve claims to be engaged in.

I was heartened to see the sharp price break in May in gold and many other commodities. However, the July Fed Action has not caused further downward action.

This news item points to actual physical factors as being the largest force in the market. Of course monetary factors always impinge on commodities prices, because they affect the ability of market participants to take positions in commodities and hold inventory. All things being equal we would expect rising interest rates to moderate commodities price increases, even if they are physically based.

On the other hand the Hulbert’s Peak proponents have claimed that rising oil prices have been driven by physical facts. This news item would tend to confirm that view.

I took the money bubble view, because that is what happened in the 1970s and 80s. I am not yet persuaded by the physical view.

I would be interesting to know if there is information about the amounts of inventory at tank farms and on ships. If they are not at abnormally high levels it would be another data point for the physical view.

Robert, Stuart Staniford has a detailed discussion of these data.

Dr. Hamilton:

Your right, my strategy was simplistic and incomplete. I see it as a shock, or impulse. The team is looking to initiate momentum, reach the maximum price possible, and to maintain the element of surprise, up and down.

The team buys at a strategic time, driving the price up. There is a series of automatic “stops” that are set in the market. They are triggered on the buy side increasing the momentum, the price continues up. The team never knows for sure if they will attract other teams to join in, so they tend to sell some of their position into the momentum to mimimize exposure in case the ponzi doen’t take.

There exists a number of natural buyers who have to buy for business commitments or whatever. If the team can scare the daylights out of them, they will start to buy. Meanwhile the price is going up, vertically.

There is a time of the day when the brokerages and exchanges make margin calls.There is a group that is forced to cover margins. The price goes up.

The momentum hedge funds are always waiting to buy (or sell) “contracts”.

The latest groups in the commodities run up seem to be pension funds and insurance companies.

At this point it gets dicey. You have to get the news wires to report the story. You also have to get your analysts, TV commentators, companies, and everyone else you can think of into the story.

You discredit the non-believers. You hammer the shorts so badly they run away.

There is still an underlying constant group buying contracts, at the market price.They don’t have the luxury of taking the risk that the market price is phony.

The point is to do scale in buying. Buy the most at the beginning to intiate the momentum and then taper your buying as the price goes up and others chase the market. You can also initiate a sell off for a few days. If it’s done into the momentum, you can unload most of your position on someone else.

The producers are not going to ask less than the going price. If they smell shortage, and they have market power, they will hide inventory.

Once you get the price up 10 or twenty percent (100 %), be the first to sell and start the downward spiral. Or start an ETF and get other peoples money to inflate the thing.

Yes, it ends with losers.

I recommend going to barchart.com and looking at the natural gas “chart” (scam) June-Dec 05. Courtesy of the futures market.

I don’t know what the ratio of paper to physical is in the oil market. In copper, I read that it was 80 paper to 20 physical.

Oh yea, the Chinese are short 10 gazzilion tons.

In response to what Yin is saying, there does seem to me to be arguments for the view that this can happen. There are models of bubbles in which it can be rational to participate for a while. Basically, if you believe there is a bubble going on, you should also stay in the market (long on oil let’s say) as long as you believe that the incremental price increase you are most likely to get exceeds the risk that the crash is going to occur today. Thus it can be rational for everyone to participate together in the bubble. Obviously, when the crash comes, the people who get out in time will profit, while those a little slower will lose big time. Since the risk of a crash is presumably monotonically increasing with the departure of prices from the “fundamental” value, this is one of the reasons for the idea that bubbles should show super-exponential price increases (it takes a higher and higher premium to keep the rational bubble followers in the bubble, and once the sophisticated players start to bail, they all bail together in a hurry and the bubble is over.

However, I’m not persuaded it’s happening in oil at present: stocks are not increasing (on a global forward supply basis), and the price rise is not super-exponential.

Furthermore, the daily cost of renting an oil rig has increased by a factor of more than 5 since 2002. So that big rig count rise in Saudi Arabia is anything but cheap. I don’t they’d be doing it needlessly.

http://www.theoildrum.com/uploads/rigrateGOM.jpg

I read Stuart’s post. It was very informative. I am still torn. This fellow is sure that it is a speculative bubble. I think we will not know for 6 to 9 months and a couple of more cranks on the Fed’s Machine. I was convinced that the stock market was in a bubble by early 1999. Here I am torn.

I think oil field services might be a safe play here.

That surplus oil Saudi is taking offline is likely high sulphur, heavy crude most refineries can’t handle, so why pump it? Their light sweet crude has likely peaked, why else would they be renting every oil rig on the planet?

There is geopolitical risk and speculation built into the price of oil, as well as understated inflation. But that is on top of the underlying dynamic of increasing demand, falling discoveries, and flat production. The odds of seeing $40 oil again, outside economic collapse or some pandemic, seem remote.

Over at A greek speculator’s journal is this quote:

The last sentence seems dispositive: It doesn’t seem to me the problem is in the futures market. The reason Mr Naimi cannot find buyers for his oil, if indeed he has any more to sell, is that he won’t lower the price until they can afford it. The fact that there’s no-one else willing and able to undercut him is a testament to the fact that there must be a lot of folks having trouble increasing production to take advantage of the current high prices.

You can debate whether Saudi Arabia has the oil but just won’t sell it at an affordable price (as Mr Naimi is saying), or they don’t have it (as his skyrocketing spending on rigs might suggest), but the logic of accepting at face value “there’s no demand for actual oil so we have to shut-in production”, from someone who is refusing to lower prices escapes me.

JDH, interesting points of view.

with regards to the bubble…we are only in a bubble if the market thinks we are in a bubble..and therefore we are not…

the futures market has been showing some very predictable traits…for example, new money buying at the end of the financial quarter…. if we were in a bubble would that really happen??

speculation, according to report I read, has provided security to the oil markets, especially to the supply side. for example, Pre-2004, as crude prices rose, refiners would cut inventories to protect margins. in doing so, they would increase their exposure to supply disruptions. as prices dropped, refiners would increase inventories, further undermining prompt prices.

speculators are blamed for the continued contango market, but in my opinion this is the safest bet with regards to modern day geo-politics. The USA cannot afford to risk having a supply shock, hence, higher prices and higher stocks are more important than a demand driven model.

i think the important factor today is not a bubble but renewed fundamental tightening. will supply constraints prevent the market from further building stocks due to capacity constraints????

the above post should say,

at the beginning of a new financial quarter..sorry 🙂

Carnival of the Capitalists – July 10, 2006

Welcome to this week’s Carnival of the Capitalists, a weekly roundup of the best business articles posted by bloggers. This edition of the Carnival of the Capitalists is utilizing the CotC hosting template provided by Gongol.com. I hope you like…

Isn’t there an academic economics explanation called “the greater fool theory?” Sure works in the real world!

As to “nonfundamentals speculators are eventually going to get slaughtered,” that’s a bit broad to lump all speculators into a single class. There are, at least smart speculators, foolish speculators and speculators with enough power to manipulate the market. Sure, it’s easy to make money when the wind is at your back and you’ve got money to risk and the balls to do so.

The hidden assumption is perfect knowledge by all parties. Given the debates about Saudi capacity and Chinese consumption data we’ve had here and on Oil Drum, I see no reason to suppose that all market participants have perfect knowledge. That’s been Matthew Simmons’ quest – to improve production data. I wish him luck but I think it is not realistic.

Two other market news items I’ve recently heard – Iran has started gasoline rationing and Chinese oil consumption has jumped again.

hahaha balls to do it…it does take balls in the energy, the p&l swings are huge.

if you assume markets are effecient; then the price reflects all market knowledge, so someone knows whats going on…

non fundamental specs wont get murdered; they will be the first to get out as they are broadly techinal traders… a change of trend and they are going to flip… its the “intermediary-fundamental” traders that will get slaughtered as they will always have a bias to either techs or fundamentals at any giving time… but they also have the biggest winnings as when they catch it right they do catch it!

in my opinion – i beleive iran played the UN so beautifully…. by it i mean, what a bargianing chip, they stop what the US is most threatened about and they get trade agreements, energy, infrastructure… does anyone not agree????

Stuart Staniford:

“The reason Mr Naimi cannot find buyers for his oil, if indeed he has any more to sell, is that he won’t lower the price until they can afford it. The fact that there’s no-one else willing and able to undercut him is a testament to the fact that there must be a lot of folks having trouble increasing production to take advantage of the current high prices.”

“You can debate whether Saudi Arabia has the oil but just won’t sell it at an affordable price (as Mr Naimi is saying), or they don’t have it (as his skyrocketing spending on rigs might suggest), but the logic of accepting at face value “there’s no demand for actual oil so we have to shut-in production”, from someone who is refusing to lower prices escapes me.”

Why should Saudi Arabia lower their oil prices?

Where is your rock solid evidence that global demand for Saudi oil is running high at the moment?

Why are you whining over what Saudi Arabia is or isn’t doing?

Anonymous, I don’t believe that Stuart or I are whining. Instead, we’re simply observing that Saudi actions and market realities are inconsistent with the official Saudi explanation. We raise this issue not so much as an intended criticism of the Saudis, but instead to help shed light on the facts of what is actually going on.

Nor do I believe that we are claiming that demand for Saudi crude is currently high– I give several indications in the post above of the possible nature of decline in demand for certain Saudi grades. Instead, the claim is that the Saudis have cut production, and that this cut in production is an important explanation for why prices are high. That is a statement of objective fact, with which you may agree or disagree.

Why should Saudi Arabia lower their oil prices?

SA would want to lower their prices if they thought the price would drop in the future. The fact that they don’t do this means that they feel that the oil will be worth more in the future.

Where is your rock solid evidence that global demand for Saudi oil is running high at the moment

The Saudis are not inclined to spur demand by lowering prices. This suggests they feel they are selling enough at the current price. If they wanted to spur demand they would be willing to accept lower prices

Why are you whining over what Saudi Arabia is or isn’t doing?

It calls in to question the reliability of their production forecasts

I believe there is cause for “whining”. The Saudi’s have said their policy is to reduce prices something more reasonable, and that they think prices are too high. If they then proceed to say that they’re not willing to discount, then they’re breaking an important promise.

I was just reading “Crop Circles in the Desert: the Strange Controversy over Saudi Oil Production” by Michael Lynch. His Figure 8 shows the number of rigs in Saudi Arabia dating back to 1977. His curve is higher than the one you show, and it fluctuates a lot. It was 29 rigs around 1980. One could argue that the recent increase in rig number is not an anomaly; nor even very interesting.

Thanks for the reference, Steveb. I found an online version of the Lynch diagram here. But did I understand you to suggest that his curve is higher at some historical dates than the one plotted here is currently? Note the rig scale on the right-hand axis above is currently at 43, well above the 1981 local peak to which you refer at 29. I would interpret Lynch’s point as that the increase in rig count up to 2005 was within the realm of historical experience, but what has happened since then is something new.

If we assume the following are facts:

1. SA is not producing as much oil as previous years, and

2. SA has increased active wells over previous years

Doesn’t this imply (using Occam’s razor):

3. SA *can not* produce as much as previous years?

Once the economics of “shale oil” kick in, SA is toast.

Production cost,,supply, demand of the physical need not have much of anything to do with the pricing of Paper barrels unless, of course, efficient market assumptions are made. The vast majority of the trade has no intent or ability to take delivery, though a few of the largest players have leased storage.

Matt Simmons did a paper on this in 1998, finding that other than for a bief period in ’96, fundamentals had not entered into futures and spot pricing from the time of the MG induced price drop.

It is a mistake to apply general equilibrium notions to what has historically and remains a Managed production.

correction: fundamentals do enter in but ceased to be determinant over any short, medium term.

‘Fundamentals’ in this case have more to do with the degree of production Planning and management including inter-OPEC tensions, relations between the integrated majors and both OPEC and non-OPEC members.

Comparing the rig graphs, I was trying to make two points.

FIrst, during 2000 to 2005, the Oil Drum graph fluctuates between 16 to 20 rigs, while Lynch’s graph has 25 to 37. Thus there seems to be a discrepancy between their sources.

Second, by looking at the longer period of time, one could argue that the current level of rigs is not a very significant increase, or an indication of something unusual. It might indeed be, as Lynch suggests, an effort by the Saudis to increase their production capability. As the Saudis said they would.

Juan,

Thank you for seconding my note of the inapplicablity of the efficient market postulate. That’s another way of saying no one has perfect information in this market.

The Saudis are not helping. Prof. Hamilton’s multiple postings noting the inscrutablity of various Saudi statements are either a professional economist struggling with a challenge to his field’s dominant paradigm or else a teaching moment about its limitations.

The Saudis continue to provide DISinformation. Sometimes this is for economic reasons and sometimes for political/military reasons. There is a war on and all’s fair.

As a note to steveb, increasing rig counts are more likely an atempt to MAINTAIN, not increase, their production capability.

Basically it’s simply a broken pricing mechanism (at least compared to every other market I know, stocks or commodities).

Since there can practically be no arbitrage between futures and physical market (as the types of crude eligible for delivery represent minimal % of production), oil futures trades like a paper stock, in a bull/bear struggle. Supposedly speculators are “rational”, but … you remember dotcom.

IMO we now experience the opposite situation of 1998, when oil price was driven down to $10 by players in the futures and “the price-setting futures market” didn’t believe the producers, until they had cut too much.

Considering the financial bleeding of oil consuming countries, I can only think there’s a hidden agenda behind accepting this broken pricing mechanism.

Robert Mabro (with decades in the oil market) explained the issues very elogently in his 2000 article:

http://www.oxfordenergy.org/comment.php?0008

which I think is a must-read for anyone who comments on the oil market.

Here’s an extract:

“As mentioned before, because of the lack of good information on production, stocks and demand, what rules the market is the consensus view about these numbers rather than the actual situation. This has an important implication for OPEC. When OPEC has to decide on a production policy in order to reverse a price fall as in 1998 and March 1999, it is obliged to reduce production by the volume demanded by traders and not by the amount required to restore the supply/demand balance. And the market has a tendency to believe in myths, such as the myth of the `missing barrels’ in 1998. In that year OPEC, together with Mexico and Norway, reduced oil production twice (in March and June) to no avail. The oil price continued to fall. The market did not believe that the reductions were large enough. In March 1999 OPEC cut production by the large amount demanded by the market. This turned out to be too much as evidenced by the relentless price increase that followed throughout that year.

It is nice to say that markets should rule. The statement is however meaningless and indeed dangerous in its implications if one does not specify which market, and the conditions that qualify a market to rule. The oil futures markets as they exist today and for the reasons mentioned earlier on do not qualify. Yet, OPEC has to follow their whims to influence the course of oil prices and this seems to be an important cause of high volatility.”

dhatz,

I’m with you.

Moreover, I believe the blog focus needs to shift to continuous, active discussions on alternate energy policies, sources, and platforms.

It’s time to move on and focus on the transition needs, including supporting legislative actions.

This handwringing over peak oil is getting silly. How many clues do we need? Let’s move on, boys and girls.

Leon Hess, whose oil company made more than $200 million by trading oil futures during the Persian Gulf crisis … said he longs for the days when oil company barons could get together and decide prices and supply levels largely among themselves, rather than depending on the violent price swings created by traders who react to rumors and headlines.

Im an old man, but Id bet my life that if the Merc [New York Mercantile Exchange] was not in operation there would be ample oil and reasonable prices all over the world, without this volatility, Hess said at a hearing the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs held on the role of futures markets in oil pricing. Oil Baron Longs for Past, Not Futures, Newsday, November 2, 1990

Banacek – actually, ‘peak oil’ itself is silly when required information, and not just the Saudis, is NA.

‘peak oil’ is silly as a conviction perhaps?

surely it can remain an interesting possibility, even with missing data.

“The odds of seeing $40 oil again, outside economic collapse or some pandemic, seem remote.”

– of course they do. now what are the odds of economic collapse ? (inside which we will see oil at $40 again).

odograph:

You are correct and I should have been more clear.

I think it would be safe that any public statement by a Saudi Oil Minister is about as correlated with truth as “Baghdad Bob”.

I think people here, immersed in lovely analysis theory and geology, forget critical facts about politics and culture of Saudi Arabia.

The US is dependent on oil—Arabia is utterly married to it. Much of what any oil minister says is intended for domestic audience more than the NYMEX or US Treasury or whoever.

Anytime he speaks, he is putting his neck on the line. Quite literally.

If the government were to admit that in truth they had reached or passed Peak Oil and production is declining in quality and quantity, they would likely face a fundamentalist revolution. Revolutionaries would despise the royals for wasting the only resource of the nation on kissing up to the USA and subsidizing the profligate lives of 10,000 dissipative princes.

The House of Saud, including the oil minister and his family, would be executed.

This is why the true reserves of Saudi Aramco are a state secret.

Regarding the notion of Saudi Arabia cutting prices, isn’t that in reference to benchmarks, rather than outright? Isn’t al-Naimi actually saying Saudi Arabia won’t alter its spread vs a particular benchmark price in order to move oil? His reference to “leaving money on the table” tends this way. In that context, there is no suggestion in what al-Naimi said regarding other producers capacity. If Saudi Arabia chose to reduce its price relative to a benchmark price, then whatever the response of other producers, Saudi Arabia’s response would be built in. Rather like a discounter advertising that “we will not be undersold.” Other suppliers then know better than to compete on price.

Bman,

Saudi Arabia is cannot be toasted by high-cost alternatives. Saudi Arabia is the low-cost producer. It’s margins are huge. The economics of shale oil can only kick in because Saudi Arabia is taking a massive margin, or because Saudi Arabia runs out of (cheap) oil. In no sense do high-cost alternatives represent a threat to Saudi profits. Saudi reserves represent a threat to Saudi profits.

The whole “Peak Oil” theory is interesting. As some, before, have pointed out, we don’t even have a complete data set.

Better yet, why do we suppose Oil is a “Fossil Fuel”, that is, ipso facto, “non-renewable”.

There is compelling literature that suggests Oil is “abiotic”, forming deep within the Earth’s crust. There are even wells, in formations thought to have been depleting, that have ‘refilled’. (in the Gulf of Mexico)

All that aside, if we were really reaching the “end of the line” re: Oil, how do we explain large swaths of the Gulf of Mexico( and, countless other areas) being left undeveloped?

Funny that “Peak Oil” is the dominant meme now that we are officially “addicted to Oil”, which all dovetails, too nicely, with the unending rant re: AGW caused by GHG from “Fossil Fuels”.

To those who think : the “speculators” are making long cache due to their “inside info” re: Peak Oil, think again.

Certainly: “Differing Opines make’m run the Equuines…” But, is critical thinking that much of a lost art?

kharris,

As a geologist/geophysicist, I can assure you that oil is a fossil fuel and that Gold’s theories are garbage. In general, permeability barriers do not allow recharge. The deepwater gulf has some reserves left, but most have been explored and no supergiants remain. The largest field in the world (Ghawar) produces over 5% of the worlds daily supplies (5MM bopd). If it declines at 7%/yr (probably more), we meed a replacement field on the order of 350,000 bopd to come on line to keep supply constant. This is a huge field for GOM–and the world. If we have 10 or so of these supergiant fields that are declining at 7%/yr (mexico’s is dropping like a rock), then we need 10 large field to come online annually to stay even. Its simple math that economists don’t seem to understand–oil field production declines. Moreover, as production declines, the extraction costs per barrel increase.

I agree with the other poster that Saudi Arabia is lying (to save their neck) about their production capacity. Simple volumetrics (which Simmons has done) mean that the Saudi’s cannot increase their production of light sweet crude.