A few weeks ago I discussed some new research that suggests that the current negative spread between long-term and short-term yields may be a little less worrisome than earlier studies had led us to conclude, to the extent that the negative spread in part results from an unusually low term premium on U.S. bonds rather than an expectation of future declines in short-term yields. One factor that may be depressing that term premium is foreign holdings of U.S. securities.

A study of the magnitude of this effect by Frank and Veronica Warnock of the University of Virginia recently appeared as an NBER working paper (earlier version publicly available here). This study has also been mentioned in earlier discussions by Menzie as well as by Brad Setser, Economist’s View and Economics, Markets, and Probabilities.

|

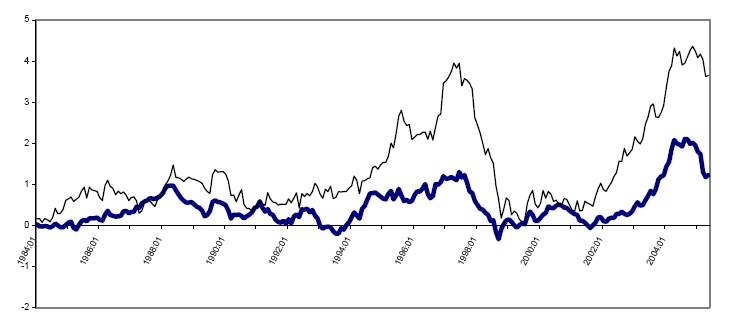

Purchases of U.S. government bonds by foreign central banks and finance ministries have in recent years been very large. We know this from those flows recorded in the Treasury International Capital System data base that are openly designated as representing official purchases by foreign governments (bold line above). However, even these impressive numbers understate the true magnitude, since some foreign governments have enormous holdings through third-party intermediaries. The thin line above represents Warnock and Warnock’s estimates of the total flows coming from foreign governments, inferred by adjusting the TIC data on the basis of surveys of the nature of foreign holdings.

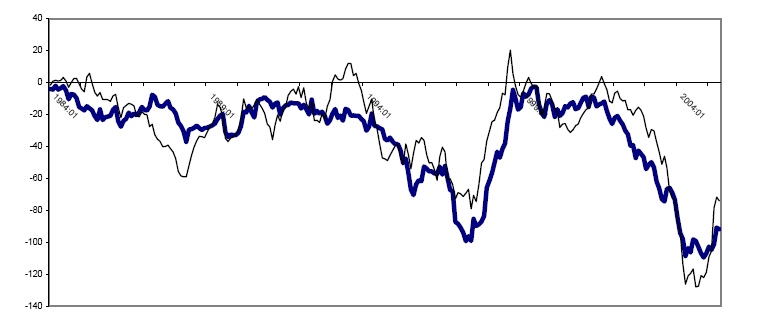

To assess the effects of these purchases on long-term U.S. bond yields, Warnock and Warnock regressed the nominal U.S. 10-year yield on these foreign purchases along with a set of other explanatory variables including survey measures of expected inflation and GDP growth, the fed funds rate, and the size of the structural deficit. The implied contribution of the foreign flows is shown in the graph below.

|

Warnock and Warnock’s estimates imply that these foreign flows are making a very big contribution, keeping the nominal yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury a hundred basis points lower than it would be if foreign flows were zero.

It is always tricky to give a causal interpretation to such correlations. East Asian countries and oil exporters are currently saving a large fraction of their income. As our current Fed chair has famously observed, this by itself could be a factor depressing interest rates globally. One way these high saving rates have been manifest is through acquisition of U.S. Treasury debt by the governments in these countries. But if these governments were instead buying some other assets with global saving unchanged, the effect on international interest rates would still be there. Moreover, arbitrage by private investors would still prevent the rate on U.S. bonds from differing too much from that in other countries, after adjusting for such factors as depreciation risk and the “safe haven” effect. To the extent that happened, the main effect if these foreign governments shifted to other assets would be on who holds which assets rather than on the yields themselves.

Because I think of arbitrage as a pretty powerful force, I have always been a bit skeptical of claims that there are huge consequences of composition effects. Nevertheless, as Warnock and Warnock observe in their paper, one might think of their regressions as capturing not a pure composition effect but a more general “international influence” that includes the global savings hypothesis. Moreover, the thought experiment of “what happens if foreign governments stop buying U.S. bonds” really needs to be spelled out more fully, articulating why the flows might change, e.g., due to a drop in the global saving rate, increased fears of dollar depreciation, or changes in perceptions of geopolitical stability. One might interpret Warnock and Warnock’s findings as indicating that the potential effects of such changes could be quite large.

|

If we were to take the view that (1) the term premium on the 10-year Treasury relative to the fed funds rate is 50 basis points lower than the historical average due to the current high levels of foreign saving and acquisition of long-term U.S. Treasury debt relative to their historical averages, and (2) a drop in the term premium itself does not signal a higher probability of an economic recession, then the current 10-year-over-fed-funds spread of -70 basis points is perhaps comparable to a historical spread of -20 basis points in terms of what it may signal about the current prospects for an economic downturn.

See how much better you can sleep knowing that foreigners are holding so much of the U.S. debt?

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

yield curve

Dallas Fed research made a similar point sometime back. I’ll accept that massive central bank buying has depressed the longer end of the yield curve. What I don’t buy is that just as deficits don’t matter, neither do inverted yield curves.

I suspect that foreign CBs aren’t sleeping so soundly with the knowledge that they are piling on losing investments. Their positions will rapidly become more untenable as losses pile on, but nobody forced them to buy this stuff so I don’t feel particularly remorseful.

Like pretty much everything else these days, US monetary policy is–you guessed it–Made in China. That is all for now, comrades.

Who would be buying 10 years when 1 year is equivalent in rates? That doesn’t make any sense.

“who would be buying ten years … ”

Let’s see, in September buyers included Norway and Brazil … and I assume PIMCO.

“that doesn’t make any sense”

It makes a lot of sense if you think ten year rates will fall further; those who bought ten years earlier this fall have done quite well …

and for central banks, it makes sense if you think US short-rates are likely to fall.

but the gap between a 4.5 ten year and 5.25 at the short-end certainly makes it costly to hold ten years if long rates don’t fall further.

But what brad setser just wrote is the reasoning behind as it has been historically. A recession would take the short term interest rates lower, so it makes a lot of sense. But now JDH and Fed (and many others) are offering an alternative explanation, which is that the rates are not low because of a recession, but just because so many instances requires those long term treasuries.

But the question here by Laurent GUERBY was that why buy 10-yr treasury now, as there’s 1-yr treasury available with higher rate IF the lower yields in the long maturity treasuries are NOT low right now because of an impending recession, but instead just because there’s too much liquidity around, especially PIMCO and other foreign central banks buying those.

Why don’t they just roll over to short term ones, for example sell long, buy short, fix that silly curve (given there’s no reason for it to be inverted)?

Occam’s razor, professor. C’mon, you guys (fed, stetser, you, etc) don’t see the recessionary data confirming what the yield curve is saying?

I’ve got to agree with charts. People have tried to find explanations to inverted yield curve many times in the past. But the reason has always been (at least for the last 50-years) that some kind of a shock was going to take the short term rates lower in the future (say 6-18 months) from the inversion. In most cases it has been a recession, but there are a couple of softlandings (1966 and 1995) that occurred too, but even they took the lower rates down. Maybe the market overreacted in 1966, but still the direction for the rates was down eventually, so was the GDP growth. In 1998 same thing again, financial crisis, rouble default etc., rates down. But none of these (except 1966) has been as steep as this one, unless there was a recession followed by it.

So if the long term rates this time don’t tell anything about a recession (this time it’s different, right?), then how amazingly did those rates start to get flat 12-months ago, with real inversion mounted in July, and everything has only pointed more and more to a slower growth, even a possible recession. Given that the inverted yield curve does not imply recession this time, it just happened and by coincidence we get all this crappy data right now. Just coincidence? Maybe those central banks, PIMCO etc. out there are more clever than we’ve thought. Dollar may decline, but it has no reason to go down for ever and permanently. The lower it goes, the higher chance is it may actually rebound later. Why not go for the treasuries, long term ones. I could buy, but I wouldn’t if I thought they were overpriced. I think the price is a bit tough, but fair. 🙂

Of course the market can be wrong, but that’s another issue then.

if i think that there is a recession coming and that it will push down yields on l-term bonds further, I would rather hold a 10 year bond than a one year, even with a yield penalty. I am in effect betting that the capital gain from holding long-duration assets in a falling long-term rate environment will more than make up for the yield penalty. If I think the yield curve is distorted by central bank demand and I think central banks will continue to buy, I also might want to hold long-term bonds for the same reason — tho at some point, i would start to worry that central banks would start to opt for deposits and one year bonds rather than ten years.

Inicidentally, some of my proprietary work (JDH, sorry about the plus, but hard to do the comment otherwise) suggests central banks did shorten the duration of their dollar portfolio in the first half of the year. THe evidence suggests that they lengthened it a bit in q3, and well, who knows for q4. My guess is that overall intervention picked up, so they are buying more short and long-term US debt. that would be consistent with a 10 year bond yielding less than 4.5%

Patriot,

You need to distinguish between rates under the gold standard and those under world fiat currencies.

Note this post from one of my friends.

“In contrast, the targeting of a short term interest rate does not directly effect money supply and it does not provide demand information. I think that using bond sales/purchases and a gold target is likely to produce the immediate result, during a period of adjustment, of higher long term interest rates….which is what the Fed has tried but failed to achieve through its short term interest rate strategy. After an adjustment period as the market accepts a new gold target paradigm interest rates should trend lower all along a normal yield curve… where the long rates may be lower than they are presently…because the premium for Fed mistake will have been reduced and the demand for dollars will have been increased…as China will have less reason to hedge.”

As noted the inverted yield curve can now be because of the market hedging against FED mistakes. Of course those mistakes could be the very actions to take us into recession.

The use of the term “savings glut” ignores the fact that much of the purchasing of long-term Treasuries is being done with freshly created “unsterilized” Yuan & Yen. So foreign central banks are stimulating the US economy in a manner comparable to what our Fed was doing until the rate hikes–except they are doing it on the long end.

Even when they are lending the US “saved money” as cheaply as they are doing, often to cheapen their own currencies, I view their actions as short-term stimulative.

I suggest that this situation is different from previous inversions.

Man, I can’t believe I did it again. Patriot, that post was from me.

Algernon,

If “freshly created ‘unsterilized’ Yuan & Yen” are being used to buy T-bills why is it that the dollar is falling against the Yuan and Yen?

Thanks professor. I have been trying to make sense of this inversion myself, wondering if the bond market (and fed futures for that matter) were just living in a fantasy world or if there was a system reason for it.

As of Friday the inversion stood at over 80 basis points I believe. I’m from the camp that says inflation indicators will prevent any loosening by the Fed. I’ve been pretty good at predicting (especially for an amatuer) considering I said that 5.25 was a foregone conclusion over 6 months ago. But how long can a know-nothing outsmart the fed funds futures market?

Dick,

The Yuan & Yen are being used primarily to buy long-term bonds (with only some recent diversification into shorter maturities, if I read Setser right). If they were not doing this continually, the Yuan, Yen, & other Asian currencies would be appreciating strongly against the US $ as we continue to run trade deficits with these countries.

Mr. Hamilton, I was wondering if you could shad some light on another issue…

Should the expected (US Dollar) Trade Weighed FX Rate fall continue to put pressure under the commodity prices? Or the causation is the otherwise? If thats the case, why?

tks

rds

Roberto

Great closing line, Professor. But, don’t quit your day job at UCSD!

If a currency trader believed that the US is close to recession and Japan is close to recovery, would he not borrow from Japan at one half percent and loan to US at 4.5%? The profit would come from long bond appreciation and currency appreciation.

Shucks, from spread and bond appreciation to more than offset currency loss?

Algernon,

Perhaps you can help me understand where others have failed.

If we are running a trade deficit we are sending dollars to foreign countries and receiving goods and services. Since there is no change in the ratio of total dollars to total goods and services, how is it that the dollar would decline against other currencies? Wouldn’t the decline need to be something other than the balance of trade?

Secondly, if the yuan and yen, being used to buy Treasuries, is new yuan and yen, why wouldn’t this actually lower the yuan and yen relative to the dollar, unless the dollar-to-goods ratio is increasing faster than the yuan and yen-to-goods ratio – in other words, unless the FED is failing in controlling the money supply?

Dick,

1st question: If the Asians weren’t buying $-denominated Treasuries, US dollars would accumulate in Asian countries where they are less spendable than local currencies. Can you imagine that $’s would be perceived to be less & less valuable to the Asians?

2nd q: In the long run, I think you are right. Right now I think Chinas money supply is growing a little less than twice as fast as its galloping GDP. About the same ratio for the US (M2 Oct’05-Oct’06 4.8%)/ GDP ~2.5%. I’m sure someone else could give you a better answer.

Algernon,

I am still not understanding question 1. If the dollars were accumulating in Asia they would not be transacting in the economy. That would seem to generate a shotage of dollars in the economy relative to goods. Wouldn’t this shortage of dollars cause an appreciation of the dollar rather than depreciation? That is unless the FED replaced the inactive dollars.

I thought that one of the classical explanations for the inverted yield curve is that it reflects the market moving capital out of the stock market and corporate investments (bonds) into recession-safe long-term Treasuries.

Any sign of this happening? Because the USA is still the world’s largest economy — and at current rates of depreciation (PC Computers vice steel mills) it requires over $1 TRILLION/year in business fixed investment just for the US economy to keep the status quo.

A major fallacy of the Bush tax cuts — if one can call deliberate misdirection a fallacy — was that it would spur the US economy. But the capital from those tax cuts went to create jobs in CHINA , not so much in the USA. Dell computer US employment, for example, has declined but its number of foreign employees has increased greatly.

Similarly, the US economy could fall into a recession without it being signaled early in the stock market –because the foreign earnings of US corps would offset the decline in US revenues.

One problem I see for the US economy is that much of its recent growth has been spurred by hot money in the form of defense spending. But that money is consumption, not an investment that yields a return. If our huge defense spending is cut at some point (e.g., 1991) then it will really hit housing and retail sectors because of the multiplier effect. Look at what happened to the Los Angeles economy in the early 1990s from defense cuts.

Comments?

I’m not sure I’m following your argument, Don. In what sense are long-term Treasuries more recession-safe than short-term Treasuries? Remember that the definition of a drop in the term premium is a drop in the expected return on long-term Treasuries relative to the expected return from rolling over short-term Treasuries. I would have thought that worried stock market investors would want to park their money in short-term Treasuries.

It depends upon whether investors are concerned about maximizing return or maximizing safety of capital.

Don’t people buy Treasury bonds in order to (a) park their capital in the safest of investments (b) collect semi-annual interest payments as income that is protected from the confiscation of local/state government taxes

Don’t they do this when they expect hard times ahead? When stocks and corporate bonds are risky? Weren’t Treasury Bonds the best investment during the Great Depression?

The problem with short term Treasuries is that they expire within a few months.

Don, the datum we are trying to explain is not the difference in yields between Treasuries and stocks but rather that between long-term and short-term Treasuries. Treasury bills are just as safe and have the same tax benefits as Treasury bonds. Yes, Tbills have to be rolled over. But the question we’re asking is why should there be a drop in the return from a long-term Treasury bond relative to what you can expect to obtain from rolling over Tbills.

JDH writes “Yes, Tbills have to be rolled over. But the question we’re asking is why should there be a drop in the return from a long-term Treasury bond relative to what you can expect to obtain from rolling over Tbills.”

Exactly. I’ll add here that the above “have to be” is a nice option. Should you need your money back from this investment, it’s risk-free after the Tbill matures. Should you need your money back from a Tbond (or a longer maturity) within same time, there is a risk that the market price goes down. For this additional risk there should be additional compensation.

Currently 6m maturity yields around 5.05% while 2-yr treasury yields around 4.58%. If we assume that nothing changed until 2 years has passed, one could roll with 5.05% income per year with 6-m bill and 4.58% with that 2-yr bond. Rolling that 6-month treasury leaves investor possibility to jump out without a risk every six months. Holding that longer maturity treasury one cannot jump out without selling the bond back to markets and possibly losing some of it’s value, thus making the true yield even worse. As a matter of fact, should nothing change, the 2-yr bond would lose some of the value as it comes closer due, of course, since the short end of the curve is higher than where 2-yr bond stands currently.

If interest rates were to rise, it would make things even worse for the investor holding that 2-yr bond, because the market price would be eroding even faster as it comes due. On the other hand the investor rolling those 6-months bills would do much better, because after every bill is due, he could buy a new one with a higher yield.

So it doesn’t make sense to buy that 2-yr with lower yield unless rates were to drop so much within 2-year period that it would actually pay at least as much as rolling over with 6-months bills. Actually it should return even more, for the additional risk one has to take. To me it looks like bond markets are betting FFR to go down to 4.0% within next year. Possibly even lower. Should that happen, it would be interesting to know what could trigger such an event.

Now keeping this in mind and noting that yields on 3-yr bond is even lower than on 2-yr (4.48%) and 5-yr is lowest around 4.45%, it makes even less sense unless the FFR drops significantly lower. And Fed has not made any such promises, rather the opposite. Looks like a strong bet against the Fed (and growth) from the treasury markets, or alternatively the market has gone nuts.

Re the comment “To me it looks like bond markets are betting FFR to go down to 4.0% within next year. Possibly even lower. Should that happen, it would be interesting to know what could trigger such an event.”

—-

1) I remember the FED making three rapid fire interest rate cuts in early 2001 after they realized they had gone too far on tightening in 2000(to compensate for the loose money policy they used to preempt any bank runs during Y2K ). But those rapid cuts in short term interest rates were too late to forestall the recession.

Is the bond market anticipating that the Fed will have to cut short term rates next spring?

2) I haven’t had a chance to analyze the flow of funds yet, but the bond market is a market and so prices reflect supply and demand.

But If big money is trying to move out of stocks and into Treasuries, it has to start early and go slow –like an oil tanker turning in restricted waters.

For example, could the rate on 10 year bonds be a reflection of large investors having to spread their purchases across a range of Treasuries? Because they would drive prices up too high if they moved their money just into short term Treasuries?

Also, are there tax advantages to having a spread over a range of maturities? I.e., so that all of one’s Treasuries don’t mature all within one year?