As always, first-rate economic analysis from Fed Chair Ben Bernanke today, and first-rate coverage from Mark Thoma and Kash Mansori, among others.

Bernanke essentially said he’s expecting 2% real GDP growth for the first half of 2007, with ongoing drops in housing investment bringing total GDP growth down to these modest levels. But Bernanke is not without his worries:

This forecast is subject to a number of risks. To the downside, the correction in the housing market could turn out to be more severe than we currently expect, perhaps exacerbated by problems in the subprime sector. Moreover, we could yet see greater spillover from the weakness in housing to employment and consumer spending than has occurred thus far. The possibility that the recent weakness in business investment will persist is an additional downside risk. To the upside, consumer spending–which has proved quite resilient despite the housing downturn and increases in energy prices–might continue to grow at a brisk pace, stimulating a more-rapid economic expansion than we currently anticipate.

Initial signs of that spillover are what caused me to turn decidedly bearish last month. I should acknowledge that we’ve seen some modest improvements this month in a few of the numbers that had me worried. I was greatly concerned when January’s drop in the index of industrial production brought that series to a 6-month low. But the recently announced February gain in industrial production brought it back up to an all-time high:

|

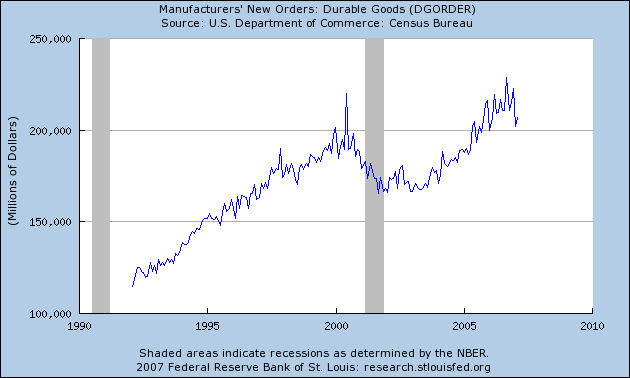

I also fretted much (and in this was hardly alone) at January’s 8% drop in new orders for durable goods. Today’s announcement that these orders were up 2.5% in February therefore has to bring some cheer, though that still leaves this measure below the values of 6 months or a year ago.

|

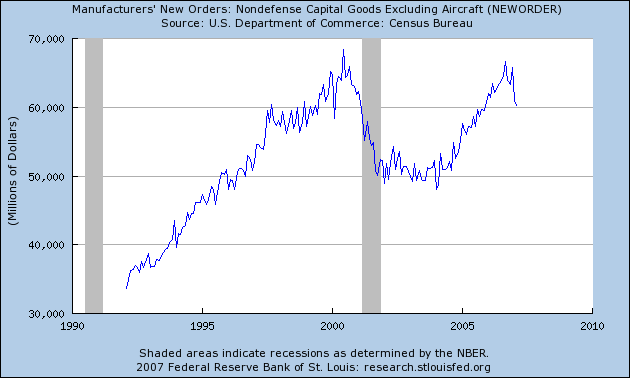

A third concern had been January’s 6% drop in new orders for nondefense capital goods (excluding aircraft), which had brought this series to a value lower than any month of 2006. No comfort there in today’s release, which reports that this series fell an additional 1.2% during the month of February. It’s hard not to be a pessimist if nonresidential investment follows residential investment down.

|

These ups and downs should remind us all that it’s easy to read too much into one month’s swing in any of these series. But that also means it is hard to recognize the downturn until it’s fully upon us. So, while Bernanke is technically correct to state that

thus far, the weakness in housing and in some parts of manufacturing does not appear to have spilled over to any significant extent to other sectors of the economy

I can’t take a lot of comfort in the extent to which these spillovers are not yet judged to be “significant”.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

investment,

Federal Reserve,

recession

“Initial signs of that spillover are what caused me to turn decidedly bearish last month.”

Professor Hamilton,

Could you elaborate on this “spillover” from housing. You’ve been pretty dismissive of the “bubble camp.” Has there been a further evolution of your views?

MTHood, you’ve raised a similar question before, and I don’t accept your premise. Since my June 30, 2006 post All eyes on housing, I have regarded the housing sector as the key determinant of whether or not the U.S. economy goes into a recession. It is precisely because that has been my view that I have devoted a high proportion of my posts since then to the question of prospects for the housing sector.

It is true that throughout that period I have been unsure, and remain today unsure, whether the housing downturn will lead to a recession. As recently as January, I was leaning toward the view that it would not. Today, I am leaning toward the view that it will. What changed my mind was: (1) I see numerous signs of weakness now outside of housing (some mentioned in the current post) that I did not see in the earlier data. (2) The stimulus that I was counting on for new home sales from lower mortgage rates has by now played itself out. (3) I now see the credit availability issue as operating to some extent separately from the level of interest rates, and the very rapid changes in the subprime market that we’ve seen recently have to make anyone more pessimistic on that score. (4) I do not believe the incoming inflation data have left the Fed much room to lower rates in the near future.

I think of all of these as reasonable adaptations to incoming data.

I further would not characterize myself as “dismissive” of anybody. I have believed, and still believe, that house prices did not increase for no reason, but were instead driven by fundamentals. One of my big concerns at the moment is whether part of those fundamentals operated through what economists would describe as a market failure. For example, I am still trying (and haven’t yet succeeded to my own satisfaction) to get to the bottom of the role that the GSEs may have played in these developments. I was in fact worried about the possibility of some market failure from the very beginning, as I believe all my posts reflect, but I am taking it a lot more seriously now as I learn more details about some of the mortgage risks. Although I recognize that many of my readers have found my discussion of “bubbles” on these terms to be splitting semantic hairs, for anyone who builds economic models or hopes to make policy recommendations, it is a tremendously important distinction as to what the ultimate causes of unfolding events might be.

How would an energy supply shock affect current economic conditions?

>>in new orders for durable goods. that still leaves this measure below the values of 6 months or a year ago.

*And* below the peak of 2000??

>> in new orders for nondefense capital goods (excluding aircraft), which had brought this series to a value lower than any month of 2006.

*And* below the peak of 2000??

As anybody knows car manufacturing represents the tip of a pyrimid of associated manufacturing and supplying.

One question i have is that when you have a war economy how exactly are you separating out the effect of war spending on the above graphs?

At the moment i dont understand how even a stabilisation in house prices will not lead to a tanking of residential investment.

Mew is often talked about as the fuel of the current boom but if Mew=new borrowing – residential investment then mew must surely have a way to fall yet and well into negative values?

Also what about mew for businesses? Is that something that is calculated?

What about the **already in place** credit tightening across the board on the ability of **anybody** to borrow money on property. How is this going to effect the ability of companies to sustain leveraged finance??

I admit i am pretty ignorant on financial matters from an economists point of view but from the point of view of the housewife balancing the books it looks grim to me

“Although I recognize that many of my readers have found my discussion of “bubbles” on these terms to be splitting semantic hairs, for anyone who builds economic models or hopes to make policy recommendations, it is a tremendously important distinction as to what the ultimate causes of unfolding events might be.”

Surely in models there are weighting factors to various drivers, and not simply boolean trues and falses.

I’d think a run-up becomes bubble-like when the bubble psychology becomes “significant.”

Maybe I’m applying fuzzy logic in a fuzzy way:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fuzzy_logic

I don’t know how to build a model with a little bit of a bubble, Odograph. Either it’s all fundamentals, in which case your model implies a statement of what the output would be given the inputs, or else your model has the conclusion that the output could be anything given the inputs.

The consensus seems to be that in many markets there were (somewhat) established relationships between fundamentals and price, and then later a divergence from that earlier pattern. Price accelerated.

I guess it reduces to the changing relationship, and whether it was a non-linear relationship to fundamentals all along, or if some other factor X became increasingly important.

When I read lines like this, factor X starts to look like mania:

“Frenzied flippers have walked away from contracts to purchase homes as the real estate market has slowed across Florida.”

http://www.naplesnews.com/news/2007/mar/28/builder_allows_customers_use_forfeited_deposits/

Non-defense capital goods and consumer spending are what we need to watch as they are most related to the “big” impact of the housing bust, weaker consumer spending and impending Commercial RE bust to follow. It looks like gooseeggs for the economy in the first quarter because both look weak.

Industrial Production will not lead this downturn much like the 1990-91 recession(IP rose into the recession!!!!) which was also a housing bust related downturn, it will be a capital and consumer spending bust damaging the service sector while manufacturing doesn’t overly feel it IMO.

I think it shows how little manufacturing means to this country nowadays(well, maybe my Midwest which still hasn’t recoverd from the 00-01 manufacturing bust). Notice the huge manufacturing boom in the 90’s. WOW. I think capacity was up to around 85% during the peek. But the bust was pretty big as well. Yet, the US economy only suffered a mild recession as the service and consumer side was saved from the dot.com fallout.

The downward pressures this housing bust is giving us, is hitting those “tender” areas ie capital and consumer spending. If we see consumer spending going down like in 1990, run run and run some more.

JDH said: “…These ups and downs should remind us all that it’s easy to read too much into one month’s swing in any of these series…”

Amen to that.:) However, the concerns you address are only indicative of an economy that’s slowing. Recessions don’t occur until there’s some evidence that conditions are on their way to becoming outright hostile, and I don’t see a shred of evidence for that. Plenty of scary headlines and statistics to “support” them, but no evidence that has real forecasting value.

Even the Wright Model “B” yield-curve indicator is stalled at about a 46% recession probability over the next 4-6 quarters. With almost precisely balanced arguments for and against Fed easing (falling home prices/rising oil prices), no change in Fed policy is likely anytime soon, so the yield-curve indicator is probably going to hold steady, as well.

As to housing, it will not and cannot become problemmatic for the entire economy until there’s at least a hint that employment is becoming problemmatic first.

I say trust the data and don’t read anything into it that’s not there.:)

Sebastian

Professor Hamilton,

Thank you for your response. I agree with much of what you say now.

Regarding the term “dismissive”, allow me to justify my characterization by citing your blog entry from June 18, 2005 entitled “Babble about a housing bubble”.

To my reading, these words come off as dismissive:

– babble

– this one only seems to pop up in

– bubbles seem to be popping up all over the place

– looking for bubbles in France and all around the globe

My larger point is that in 2005 and 2006, while others were highlighting the problems housing, lending and “liquidity” would likely pose to the economy, you were (to my reading) downplaying those threats – focusing on the “fundamentals” and “not seeing it in the data”. Now in late 2006 and 2007 your tone has changed in my view.

I’m experiencing cognitive dissonance reading your words today about housing and lending while remembering your words and tone of the past.

I agree with the assessment that we are likely to see the economy slip into recession.I see the housing sector and its myriad of woes as the culprit.i have moved chunk of money out of bills and i now sit in the belly of the Treasury curve.i am confident i have the right position but i do have one reservation.Why hasnt the job market shown somesign of distress? The economy has slowed quite a bit over the last year yet unempoyment remains at 4.5%.I would have thought it should have begun to creep higher by now

addendum to the above…..the weeekly jobless claims data refuses to break,too. they had drfited high in february but as of today it the 4week moving average has retreated and is indicative of a reasonably robust employment market…….we are well below levels consistent with economic weakness

I’m not conviced a recession is on the horizon. However, I am concerned about the Federal and National debt combined with inflation in food, energy, housing, and health care. How much growth can the US economy really have over the next ten years?

Any projections on productivity growth and relative valuation of the dollar?

JDH wrote:

(1) I see numerous signs of weakness now outside of housing (some mentioned in the current post) that I did not see in the earlier data. (2) The stimulus that I was counting on for new home sales from lower mortgage rates has by now played itself out. (3) I now see the credit availability issue as operating to some extent separately from the level of interest rates, and the very rapid changes in the subprime market that we’ve seen recently have to make anyone more pessimistic on that score. (4) I do not believe the incoming inflation data have left the Fed much room to lower rates in the near future.

JDH,

This was such a good summary of conditions it deserved reprinting. This is the crux of the problem. Thanks you.

Ben Bernanke said:

The possibility that the recent weakness in business investment will persist is an additional downside risk. To the upside, consumer spending–which has proved quite resilient despite the housing downturn and increases in energy prices–might continue to grow at a brisk pace, stimulating a more-rapid economic expansion than we currently anticipate.

While BB recognized the supply side warnings he seems to be putting his hopes into a demand side recovery. This has led the FED into errors that have driven us into recession in the past and could do it once again.

JDH, Your statement: “I do not believe the incoming inflation data have left the Fed much room to lower rates in the near future” is a huge concern. It now appears that inflation will remain steady through mid-summer but there are some indicators that we could see an upturn. Unless the FED lowers interest rates soon to allow the economy to recover they could be in an even worse situation. They could see two predators, recession and inflation, chasing them from different directions while they only have one arrow.

Be careful of giving too much weight to the bounce in industrial production. It was almost all utilities (cold weather) and autos (not sustainable

with current sales level).

Looks to me like we are sliding into stagnation — note I did not say stagflation.

Well, I like that snub of “inflation” spencer, if I may take the liberty of interpreting that oh so careful spellin.

BB may be backed by the half-baked (as I make it, being one who likes everything well done) argument that those hopeful mortgage hunters will sadly turn to renting, that recent owners will jump now rather than later back to renting in order to avoid larger losses as house prices slump, that existing housing stock (the notorious inventory glut) will sit idling away being deemed “unrentable” by …these half-baked thinkers. I did note an unpalatably large OER in the CPI basket and wondered how that could hold up now with current inventory and later with even more inventory.

I have absolutely no economic background — so I have to ask this question. Since rent is used as a proxy for shelter cost in calculating inflation, and given that there is a lag between housing prices and rent and given that in any feedback system, delay is critical in terms of whether the feedback is opposing instead of reinforcing — has that been taken into account in choosing rent as a proxy? Wouldn’t it be better to also include the cost of buying in some form to reflect the degree of inflation faster?

I should have added — since buying is expensive and rents stay high showing up as high inflation but rental demand stays high and prolongs the hangover.

The thing that makes home prices difficult to put into the CPI directly is the fact that, when the price of a home goes up, that represents a capital gain for the homeowner. Other things being equal, when you’re earning a capital gain just by living in your home, it means that the cost of living in that home is cheaper, not more expensive. The correct economic concept would be the user cost, which subtracts capital gains but adds in your interest and other expenses. In equilibrium, rent should correspond to user cost, but in practice, OER can be a pretty imperfect measure. The issue is that nobody has come up with a better way to do it.

Professor Hamilton,

Thanks for your reply. From my engineering background, I find myself equating rent to the slow-moving “integral” portion of a proportional-integral loop which is missing the fast-moving “proportional” component. And I would guess that faster reaction time would imply more volatile monetary policy. Nevertheless, your reply is some food for thought.

Has nobody ever done it? Let’s ask those municipalities if they’d like to switch to the Fed’s OER instead of the appraised values based on comparatble sales.

There is no will to do it by the Feds who need a way to underscore housing costs so that the official inflation rate is lower than the actual costs of housing. So many entitlement payments have this “inflation protection” clause that it pays to keep this figure low.

As it was recently pointed out to me by a fellow commenter, the inflation rate is based on a consumption index and therefore the investment view, the gain/loss view on stocks, bonds, commodities, is discarded…unlike the European view as I understand it, which just records the broadest money supply, M3?

There is no affect on US inflation by rising prices of Art, but those Black Velvet Beauties in WalMart are tallied as “non-durables”. The exclusion of asset prices and limitation of inflation to a consumption index seems more than incomplete to me. Is it unfair?

The bottom line is that the bears are still betting the cave on the “tapped out consumer” and praying for increased unemployment.

It’s their only hope.

One of the most notable attributes of this housing crisis as well as similar phenomena is that the great majority of amateur commenters seem to have a much more negative stance than the expert consensus. I suppose this is largely a selection effect, that people who pretty much agree with the general consensus aren’t the ones who are going to go online and post about the issue. But still the pessimists seem to vastly outnumber the optimists – you don’t get many people angrily ranting about how Bernanke is being way too pessimistic and alarmist.

This points to a genuine excess of pessimism among amateurs, and implies that there is probably a strong positive correlation between how much you know about the issue and how optimistic you are about it, just because so many amateurs are so much more pessimistic than the experts.

I’ve wondered about some of the fundamentals in the housing market in regards to prices. There plenty I don’t know, but I am concerned about 1) the rise of housing costs compared to income 2) payment stress for buyers.

For the first, especially in larger metro areas, I have wondered what kinds of fundamentals justify increases in value to match the increases in price. What is it about homes that make them more valuable now? Home prices were always a store of value before, but it seems like a pretty short term view that would suggest the net present value of future home prices should include dramatic long term price increases, especially considering the second factor – buyer payment stress / incomes.

Income data from the latest expansion shows that workers are taking home a smaller percentage of benefits. While it may be similarly unrealistic to expect that wage increases will be small for the long term, I wonder about adages suggest borrowing as much as possible. They seem to depend on wage increases and a stable housing cost to turn an oppressive payment into a managible one. If wages aren’t growing substantially, how are those suggestions justified.

I’m not suggesting that I’m an expert, but these questions have been in my thoughts for a while. I definitely see how housing values have grown, even in shifting ways as the ability to extract value from homes as increased, but I wonder about a disconnect between home prices and their real value.

Thanks

Ken, even if the benefit you’re discounting is constant, the present value goes up when interest rates go down. For example, if the current one-period benefit of owning a house is s, this benefit grows at the rate g, and you discount at the constant interest rate i, the present value is s/(i – g), which could become a substantially bigger number when i goes down.

Professor Hamilton,

I’m no expert on this either, but it would seem to me that determining the value for “i” (interest rates) has been complicated by Interest Only and Option ARM loans. That is, if a substantial percentage (20% to 40%? More in certain regions) of recent home buyers have been paying 1% to 4% “teaser” rates for a period of time, how does that figure into the calculation for “i”?

Perhaps you and others have taken this into consideration in your models. And if not, I appreciate that there may not be good data out there to allow you to do so. However, to exclude this “stealth” interest rate decrease would cause problems for a model, would it not?

I apologize if you have already addressed this issue previously.

MTHood, the above link gives a more general formula applicable to the case you mention.

Professor Hamilton,

Thanks for the link to the previous post very informative. Please bear with me for a few more questions, as I think they relate to the divergence between your views and those of a professed bubble camper like me.

1. In the comments to the post, you state:

But the calculations that I reported showed that just using the observed decline in conventional 30-year fixed mortgage rates since 2000, you can explain the lion’s share of what’s happened nationally to house prices, without any guesswork or conjecture.

With all due respect, Im not seeing that. Am I missing something? I agree that low interest rates played a large role in housing prices increases, but I dont see where you showed that this explained the lions share.

2. In the post body you state:

In a bubble, borrowers are assuming they’ll have a capital gain on their house big enough to bail them out of the deep debt they’re getting into, even though it would mean an even bigger debt burden for the next folks down the road. But one of those future buyers, if we looked ahead rationally, is going to be forced to say, no sale.

Have you seen subsequent evidence (since the June 2005 date of this post) that there may have been greater reliance upon capital gains then you previously thought?

3. Next you state:

Now, even if you readily believe that large numbers of home buyers are fully capable of just such miscalculation, there’s another issue you’d have to come to grips with before concluding that the current situation represents a bubble rather than a response to market fundamentals. And that is the question, why are banks making loans to people who aren’t going to be able to pay them back? Maybe your neighbor doesn’t have the good sense not to burn his own money, but is the same also true of his bank?

I believe you have modified your views about this given subsequent events (e.g., subprime blowup), is that true? Thats the way I read your recent posts, but I dont want to put words into your mouth.

P.S. I appreciate the time and effort your put into your blog. Your posts are thoughtful, substantial and clear.

I am tickled by Hal’s (probably amateur but possibly not) post which begins (in italics only):

One of the most notable attributes of this housing crisis *as well as similar phenomena* [suggesting more amateur] is that the great majority of amateur commenters seem to have a much more negative stance than the expert consensus.[suggesting a rude decision procedure for sorting out experts from amateurs]

identifying amateurs as critics of the expert consensus…possibly expecting a less truculent audience (positive experts and negative amateurs). Is there no market for the apologist? How will the great consensus be known and respected if not for these unsung heroes we disparage as “cheerleaders”?

Do we recreational economists give a hoot about consensus? (Let me poll this and I’ll be back in 15 min.) Do we care about “positive” and “negative”, or ” happy optimistic experts” and “angry pessimistic amateurs”?

Not terribly.

Hal….there is no amount of touchy-feely optimism or pessimism that’s going to change what’s happened to the relationship between take home pay and home prices.

I suspect what you’ve really found, is that there’s a self selection process where lots of tech saavy engineers and business folks tend to be online. And they tend to be number crunchers, unlikely to be moved by emotive content such as one might find on CNBC.

You might also find less of us tend to play 3 card monty for our lunch money.

O RP that B such an obvious amateur remark! Have you no respect for the consensus? Let me remind you that it is brim full of optimistic experts…not like some sour puss detractors who have nothing better to do than whine.

Now about this implied decision procedure for determining experts from amateurs:

This points to a genuine excess of pessimism among amateurs, and implies that there is probably a strong positive correlation between how much you know about the issue and how optimistic you are about it, just because so many amateurs are so much more pessimistic than the experts.

Would you say that is an amateur assessment or an expert one? Would you say the experts would have to consult each other and reach a consensus to be able to reply? (Would those in disagreement lose their status as experts?)

Do we recreational economists care about “consensus”?

Not lately.

RP, do you think I am wrong about the general “expert” consensus being more optimistic than the many doomsayers we find online? Look at Bernanke’s speech, he’s taking a wait and see attitude. It seems like that’s a common view among financial experts. Yet online I mostly find people perhaps like yourself, “tech savvy engineers and business folk”, convinced that things are going to go sour. This difference in perspective is what I find striking. A priori you’d think the experts’ opinion would be more reliable.

BTW I notice that Intrade.com runs a betting market for whether there will be a U.S. recession before the end of this year. Current prices imply odds of about 22%. My impression is that this is quite a bit lower than the consensus of the “cheap talk” on the net.

Anonymous: (1) I believe I would have been referring to this study. (2) Yes, the cases of outright fraud do strike me as clear evidence of this. (3) Yes, these concerns are exactly what I have been talking about recently in terms of “market failure”.

“Look at Bernanke’s speech, he’s taking a wait and see attitude.”

Right down the middle. May I take a few swings:

– Does he have a choice?

– What are his options? Yell “fire”? Take a long vacation?

– Name the last pessimistic straight-talker hired as Fed Chairman.

Thank you calmo and MTHood, for responding to Hal.

Hal – find a single Fed speech that is not optimistic

about the future. They are “experts”, but not at what

you think they are experts at.

So would you say that Bernanke’s position is uncharacteristic among professional economists? Does he really stand out as being out of step with the consensus view? Do most professionals say what commenters are here, that Bernanke can’t tell the truth about how doomed we are because that would cause so much trouble?

Hal,

What is the track record of so-called ‘professional economists’ in correctly predicting bubbles and recessions in the last 40 years?

Maybe you can tell us about your own record first and give a reference to your papers or internet postings? If you have been a ‘professional’ a short time, maybe the last 20 years?

Unlike in a science, economists disagree on the same things alll the time and have been wrong more often than not. That hardly inspires confidence in the ‘experts.’

To me the best example of this is Greenspan, who initially warned about ‘irrational exuberance’ but later started talking about ‘productivity’ gains fundamentally changing things and reassured the public that the stock market was not in a bubble–even as he privately continued to worry about it.

If the standards of scientific professions were applied to economics, a majority of the people you call ‘experts’ would be without a job today.

Ted, let me ask if you agree with me that professional economists are in general less worried about the economy tipping into recession than amateur commentators in forums like this one?

And now, your criticism is that professional economists are no good at predicting this kind of thing, so it doesn’t matter what they say?

Does that mean you’d rather believe the amateurs than the professionals?

Ted, if my economic theory implies that variable y should be impossible to forecast, and you then find I am unable to forecast variable y, would you conclude that I don’t know what I’m talking about?

Also, I’m curious how you define an “economist” (who is bad at these things) as opposed to the group who are good at these things. Is an economist someone who tries to understand economic variables? Is it someone who is paid to do so? Is it someone who is trained to do so? If all of the above, is it your claim that the less one tries to understand, the less one is paid, and the less one is trained, the better job one will do?

One last question– are you certain that this world view you have arrived at is due to the fact that you have a more “scientific” basis on which you’ve founded your conclusions than other people?

Don’t you just love all these questions?

You figure not all of them are rhetorical?

Can I venture a provocative statement to break this interrogative spell?

I must…I’m a big fan of Hal, no question about it. I refuse to entertain any doubts whatsoever about this self-evident fact: Hal is, for all those appearances to the contrary, inflammatory…a modern day Socrates.

You think not? You think a consensus will prove that he is an ordinary citizen on the quest for some Truth about negative amateurs and positive professionals…like he says?

You can’t be as flame retardant as that…can you?

I can’t get over Hal and his contribution which I need to repackage and market (the equivalent of intellectual CDOs maybe) before the light fails.

I think Modern Day Socrates was a good guess but not a bull’s eye (or as Setser might say, “off”).

The clues for me center around Hal’s fixation (How can you not be fixated on Hal’s fixation?) on consensus, optimism, pessimism, and authority (expert, amateur)…all derivatives of that Higher Pursuit which had such a disappointing yield.

Now I don’t know if Hal is an authority on the sociology of knowledge, but there is no denying making sounds like “I don’t know.” is not a recipe around which you can build consensus and exercise bountiful and optimistic authority. Face it: Socrates’s position is not marketable…making for opportunities for experts, consensus and authority. [This B Hal’s message, maybe.]

So it matters less today about whether our statements are true and accurate and offer some guide to inform our opinions and future actions.

We are a forward-looking people, revisiting and remodeling the past as it serves our aspirations.

The President makes statements that are (in his own words) “aspirational”, hopeful and incredibly, still somewhat authoritative. We get behind the authority and those aspirations and the future will unfold according to that rationality –not your pessimistic counter-productive noodling that tracks past aspirational performance.

We are chided for asking whether the statements are true…that is just so pessimistic.

Is Hal a Quaker?