Last Tuesday, there was a unique joining of three subcommittees to address the issue of alleged Chinese currency manipulation. Here’s Steve Roach’s assessment [1], Mish’s view [2], and news accounts by CNN [3] and by WSJ [4].

With so much heated discussion about currency manipulation, it might behoove us to review the current state of the art regarding measuring currency misalignment.

There are as many – – or more – – measures of equilibrium exchange rates as models of exchange rate. This is the subject of a recent Treasury Occasional Paper entitled “Equilibrium Exchange rate models and misalignments,” written by T. Ashby McCown, Patricia Pollard and John Weeks [pdf]

The authors write:

It is difficult for any model to describe adequately, and with a firm empirical basis, all features of modern economies that are relevant to determining exchange rate movements. This reflects in part the difficulty of modeling international financial markets and capital flows.

Economists have developed a variety of methods to estimate equilibrium exchange rates. The methods differ considerably in their construction and in their estimations of equilibrium values. In some sense, comparing the models is similar to comparing “apples and oranges” because they can radically differ in structure and can even use different measures of the real effective exchange rate. Often, they are attempting to measure entirely different kinds of equilibrium. That does not mean the models do not provide useful information. To the contrary, they provide valuable insights, but one must recognize that they are limited by the use of somewhat simplified structures, which are often necessary if they are to have a reasonable empirical underpinning.

Those shortcomings aside, practitioners have provided us with a variety of estimates of equilibrium values and measures of over- or under-valuation. Although the range of results can and often do vary considerably, it is possible to draw certain inferences about misalignment provided the results are drawn from a variety of models and the results are largely similar in magnitude and direction. This information should be supplemented with assessments of other reasons why the exchange rates, during relevant periods of time, might deviate from perceived equilibrium values.

However, the ability to draw inferences and make comparisons from different equilibrium exchange rate work could be substantially improved. Apart from the “apples and oranges” of different deflator indexes, models are often run at different times and the structure and particular features of the models used are unclear.

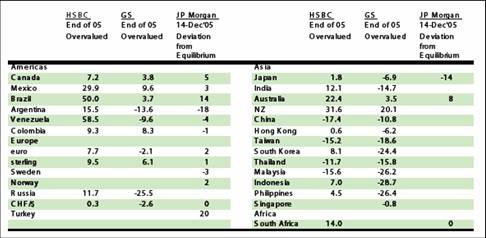

I found one table particularly interesting. It compares the estimated misalignments by three private sector models for a given time period (end of 2005).

Source: T. Ashby McCown, Patricia Pollard and John Weeks, 2007, “Equilibrium Exchange rate models and misalignments,” Occasional Paper No. 7. [pdf]

The models are described thus:

- The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), with some strong caveats, estimates long-term, 5-8 year, bilateral exchange rates based on calculating a rate that would be consistent with long term external balance.

- J.P. Morgan Securities uses a behavioral equilibrium exchange rate model for emerging market countries, with fundamentals of productivity, terms of trade and trade openness to estimate real equilibrium exchange rates. The model provides a measure of currency over-valuation or under-valuation based on economic fundamentals. Short-term dynamics are described by an error correction form of the model. Morgan bases its estimates of the fair value of currencies, defined as the exchange rate consistent with the equilibrium in both domestic and foreign markets, more generally on the basis of fundamentals such as productivity differentials, external prices, country risk and interest rate differentials.

- GSDEEMER of Goldman Sachs is a behavioral equilibrium exchange rate model with long-run equilibrium exchange rates determined on the basis of relative productivity, the terms of trade, international investment position, trade openness and G-3 real interest rates. The equilibrium exchange rates in the initial part of the exercise are bilateral real exchange rates against the dollar. In a second stage, bilateral nominal rates are derived in an error correction model by assuming that the nominal rate carries all the burden of adjusting to a medium-term equilibrium.

I largely agree with the assessments contained in the paper. Furthermore, the table highlights the statistical uncertainty surrounding the estimates (discussed in the context of the RMB in this post), but also model uncertainty — namely that we are unsure of what goes into the model specification even when the motivations are similar (as in the J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs models).

A slightly less skeptical view on exchange rate models is presented in this post.

Technorati Tags: dollar, equilibrium exchange rate,

currency misalignment,

overvaluation,

undervaluation

The paper “The Renminbi Equilibrium Exchange Rate: An Agnostic View” by Bouveret et al discusses on pages 20-27 why equilibrium exchange rate models (PPP, FEER and BEER) are not suited for developing countries, specifically China:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=923980

Also, if Kash Mansori happens to read this comment, there are two more reasons given why China does not want the RMB to appreciate on pages 7 and 16.

Charlie Stromeyer: Thanks for the reference. When it comes to equilibrium exchange rate models applied to less developed economies and emerging market economies, I think the most exhaustive and thorough assessment is in the edited volume by Lawrence Hinkle and Peter Montiel, Exchange Rate Misalignment: Concepts and Measurement for Developing Countries, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Regarding their assessment of why China wishes to keep the RMB weak, I’m a little less persuaded about the FDI/technology transfer argument, given that the Chinese have eliminated the tax break given to FDI. The point on page 16 is one that — in my mind — supports the proposition that macro management would be easier with an appreciated exchange rate.

Mish said “The problem is not that the rest of the world consumes too little the problem is the US consumes too much.”

My question is this. Isn’t the American consumer behaving rationally when confronted by goods which are essentially “cheap” due to the undervaluation of the yen and the yuan? He spends rather than saves.

Oh, and one other point. The Chinese and Japanese and everybody else on the planet with $’s (save perhaps Russia) recycles their $’s into US fixed income instruments, which in turn depresses US interest rates, thus providing additional disincentives for domestic US saving. Isn’t the US saver then acting rationally when confronted by “too low” US interest rates?

Isn’t the US saver then acting rationally when confronted by “too low” US interest rates?

Great point. Currency undervaluation, trade deficits, and the savings rate are all the same issue.

If you can explain to me why 120 yen to the dollar makes sense at the same time that the pound is $2, I would be forever in your debt. It makes absolutely no sense, except that the Japanese are mercantalists. And mercantalism probably isn’t even in their own best interests!

gab: The answer to both your queries might be unambiguously yes if one thought (1) consumer internalized the “correct” assessment of income streams they thought they were going to receive into the future, as in the optimizing intertemporal model of the consumer; (2) that the low real interest rates were entirely due to foreign purchases of US Treasuries, with no role for distortions attendant super-expansionary monetary policy; and (3) no distortions due to government spending. Well, having written part of my dissertation on (1), I’m dubious there. Regarding (2), I don’t think Warnock et al. attributed the entire deviation of rates from that implied by a standard bond pricing model to foreign government purchases, let alone foreign purchases. On point (3), well, I’ll let you decide (i.e., do you think we’ve been pursuing a reasonable fiscal policy?).

Professor Chinn (and Kash Mansori if he happens to read this), I found two additional reasons why the Chinese would not want the RMB to appreciate too much in this paper by McKinnon and Schnabl:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=905503

From pages 30-31: “First, we have shown that a fixed exchange rate against the dollar ensures asset market equilibrium between the creditor country China and the debtor country United States. By credibly fixing the exchange rate, deflationary pressure and the fall into a zero interest rate liquidity trap is circumvented. A detrimental stop-and-go in monetary policy is avoided, which further contributes to a stable growth performance. Second, in labor markets, uncertainty is reduced under fixed exchange rates because trade unions and enterprises can more easily keep wage settlements in line with productivity growth. To this end, China might do well to keep its exchange rate tightly pegged to the dollar as long as its economic catch-up path continues and capital markets remain underdeveloped.”

Prof Chinn – I don’t know that the US consumer studies the “intertemporal model” (whatever that is) prior to tapping the HELOC for the new Hummer. He just figures that 5-6% looks pretty cheap given where he’s borrowed in the past (and it’s tax deductible, sort of) so it looks like cheap money.

Also, US interest rates are somewhere in the neighborhood of 100 bps lower than they would be (Bill Gross’s number, not mine) sans foreign purchases. That’s not a huge interest rate differential, but it could be enough to make a small difference in the incentive to save.

And lastly, in my view, fiscal policy has been mildly expansionary. If anything that should be mildly inflationary, thus leading to higher long term rates than would be the case, right?

Menzie,

Thanks for this. Congress is grasping at exchange rates with the same gusto that they rushed into Keynesian economics and the decoupling of the dollar from gold. They will promote anything that will allow them to perpetuate the illusion that their economic Fascist policies are not destroying wealth. (For those who may not understand economic Fascism is not pejorative but a description of policies that allow private ownership of business under government control of production and distribution.)

gab, I did not take Mish as saying that consumers were behaving irrationally. I took it that he was saying the direction of congress was ignorant because consumers will act rationally and their actions will expose the protectionist’s grand schemes for the foolishness that they are.

Menzie: on (2) I think you can make a case that US monetary policy is no longer super-easy. Certainly us policy rates are now the highest in the g-3, and i don’t think various quantitative indicators of money growth tell a vastly different story. the puzzle — at least to me — is that the rise in policy rates has had such a small impact on long-term rates. and there i would probably put more emphasis on the impact of central bank purchases than you do. my reading of warnock and warnock is that foreign demand for bonds — whether from C banks or oil funds — does have an impact. China alone bought about $200b of long-term bonds from mid 05 to mid 06, and that total has only increased. $300b is a low end estimate for China’s purchases in 07 — more and more analysts are increasing their estimates of china’;s 07 current account/ reserve growth. (I forward you stephen green’s take on the h2 06 chinese current account data)

incidentally, FRBNY custodial accounts show a $500b annual pace of increase for all cbs holdings of agencies and treasuries, and that probably significantly understates total central bank purchases — my guess is that the warnock and warnock measures would put the impact of this at around 100 bp (tis about 4% of GDP), though it depends a bit on which warnock and warnock study you use. would you argue that this is too high an estimate?

so I personally would put a bit more weight on gab’s line of argument …

it increasingly seems to me that some important potential channels for adjustment are blocked by cb intervention, which is one reason why the us trade deficit remains as large as it is even tho us growth has slowed relative to world growth.

gab wrote,

And lastly, in my view, fiscal policy has been mildly expansionary. If anything that should be mildly inflationary, thus leading to higher long term rates than would be the case, right?

If inflation is monetary how is it that expansionary fiscal policy is inflationary?

i would argue that for the last two years fiscal policy has been mildly contractionary (the fiscal deficit has fallen) — tho that may be changing.

brad setser: My arguments weren’t that we couldn’t explain the consumption and trade deficit surge as a consequence of these factors and policies; on that point, I think you and I largely agree on the sources of the current situation, even if we disagree on the apportionment of blame. Rather, I question whether they are “equilibrium” phenomenon in the sense of being sustainable. In particular, the consumption binge — as well as the housing boom — strikes me as the consequence of non-optimizing behavior. Given that presumption, then the resulting exchange rate does not strike me as an “equilibrium” exchange rate in the sense of sustainability.

On the second point of whether fiscal policy has been contractionary, I agree that it has become less expansionary over the past two years, as measured by the cyclically adjusted budget balance. But we are still running a two percentage point of GDP deficit even at full employment (at least according to the CBO). So I’d say we’re still running an expansionary fiscal policy.

In particular, the consumption binge — as well as the housing boom — strikes me as the consequence of non-optimizing behavior.

I know where you are coming from with that comment, Menzie. But guys like Soros and Buffet have been betting against the dollar since at least ’05, and getting killed at it, at least in terms of the yen.

So it may be non-optimum behavior, but it has been non-optimum for quite a long time (and not just back to 2001, either. Our consumption boom started in the ’80s).

Why is it different now.

Dear Menzie Chinn,

i’m glad you refer to my paper in your blog. Concerning the assessment of equilibrium exchange rates (EER), i think that they should be assessed regarding to the objective pursued by the authors. For example if ones wants to label China as “a manipulator” it’s easy to estimate an EER using a model that fits this specific hypothesis, e.g. PPP. I have to admit i’m quite confused about the issue of estimating EER given that even if we were able to define accurately an EER the crucial point is about dynamics: How will the actual exchange rate converge to its equilibrium level? But most EER models don’t specify the dynamics (FEER for instance) or use an econometric framework (the VECM for the BEER) without an accurate desription of the main factors affecting the dynamics (wage-price loop, expectations, economic policies, real rigidities, hysteresis etc…). Hopefully for researchers there is more to do in the next future