One interpretation of recent global capital flows is that the collapse in investment in East Asia post-crisis, combined with stable saving rates in ex-China developing Asia, led to an excess of saving in that region (so really the term of “investment drought” is better). Note that there was no excess saving until the collapse of unsustainable lending associated with bubbles, or crony capitalism, or — in other models — behavior of investors implicitly “insured” against losses. While this is a voluminous literature, it’s interesting to me that few analysts have observed that a similar occurence can not be ruled out in the current unfolding drama in the ever expanding but always containable subprime mortgage crisis.

First a refresher on theories regarding the origins of the East Asian crises: McKinnon and Pil (see their 1999 survey) was an earlier contributor to the argument that implicit government guarantees could induce overborrowing fated for an unhappy ending. In the post-crisis period, Corsetti, Pesenti and Roubini (1998) and Dooley (EJ, 2000) presented moral hazard interpretations — in the former, it’s primarily internal guarantees, while in the latter, implicit guarantees by extra-national entities take on an important role.

Borrowing pushed up investment to high levels, driving down the efficiency of physical capital (see e.g. Chinn and Kletzer for documentation).

Second, B. Algieri and T. Bracke (2007) have uncovered some interesting diversity in current account adjustment in developed economies. From the nontechnical summary of “Patterns of Current Account Adjustment

Insights from Past Experience”, ECB WP 762 (June 2007):

The paper reviews the experience with current account adjustment in industrial and systemically important emerging market economies. It looks at episodes where individual countries recorded an improvement in their current account position that was relatively rapid (within 4 years), substantial (exceeding a predefined, country-specific threshold) and sustained (no subsequent deterioration). We identify 71 episodes that meet these criteria since the mid-1970s.

A review of such episodes can help address important questions about current account corrections, for instance on the occurrence of economic slowdowns or large currency movements as drivers of such

corrections. This allows to verify empirically some of the main results from the theoretical literature, such as Obstfeld and Rogoff’s (2005) findings on the need of a real effective exchange rate depreciation. General interest in these questions is intricately linked with the widening global imbalances, in particular the current

account deficit of the United States, which rose to 6.5% of GDP in 2006. Although today’s global imbalances are unique in many respects (e.g. unprecedented scale, unique financial dimensions, importance

of structural factors in surplus countries), empirical regularities from the past may still be informative to understand the likely adjustment mechanism of the US current account deficit.

Looking across the 71 episodes, we find that adjustment was on average accompanied by some slowdown in real GDP growth and some real effective depreciation in the deficit country. This finding is not new. It is in line with a large body of empirical literature on current account reversals. However, these average trends mask an unusually large degree of heterogeneity. In roughly one-third of the cases, economic growth accelerated, rather than decelerating, and also in one-third of the cases, the real effective exchange rate

appreciated, rather than depreciating. The paper argues that this diversity makes any meaningful inference difficult.

To enhance inference, we classify episodes into groups, based on the main adjustment characteristics. This is done with cluster analysis, a technique based on numerical optimisation that requires minimal judgement on the part of the user. The analysis leads to a classification in three groups, which we find to be robust and to

exhibit significantly different macroeconomic and financial trends. In a first group of “internal adjustment” cases, there is a slowdown of real GDP growth but not much change in the real exchange rate (even on average a slight appreciation). In a second group of “external adjustment” cases, the real exchange rate depreciated but there is not much movement in real GDP growth (even on average a slight increase). In a third group of “mixed adjustment”, the adjustment is characterised by a combination of slower economic

growth and a depreciating exchange rate. Developments in this group are more pronounced than in the two other groups, pointing to the crisis-like character of this third group. Besides these different real GDP and exchange rate characteristics, the three groups also exhibit different developments in terms of imports and exports, domestic demand components, financial variables, and global variables.

Taking the results one step further, we analyse what explains the type of adjustment. An important finding is that the three adjustment types are rather evenly spread across countries, suggesting that the type of adjustment is not a function of the size of the country, its degree of openness, its degree of industrialisation, or the region to which it belongs. Instead, results from a multinomial logit model, estimating the likelihood of the three types of adjustment, suggest that adjustment patterns are mainly a function of the underlying

economic problems in the deficit country. Internal adjustment seems to be common among countries that are at an advanced stage of the cycle and that are experiencing buoyant domestic demand growth, external adjustment is more likely when the exchange rate is overvalued, and mixed adjustments are typically signalled by a combination of on overvalued exchange rate and indications of an overheating economy.

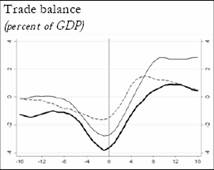

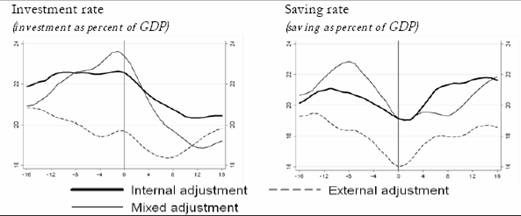

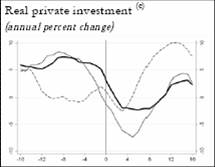

These adjustment paths are illustrated for some variables of key interest (to me): trade balance to GDP; investment, and saving to GDP ratios; and real investment.

Trade balance to GDP ratio in adjustment episodes. Thick is internal adjustment, thin is mixed adjustment, dashed is external. Source: Appendix F, B. Algieri and T. Bracke (2007)

Investment to GDP, Saving to GDP ratio, in adjustment episodes. Thick is internal adjustment, thin is mixed adjustment, dashed is external. Source: Appendix F, B. Algieri and T. Bracke (2007)

Real investment in adjustment episodes. Thick is internal adjustment, thin is mixed adjustment, dashed is external. Source: Appendix F, B. Algieri and T. Bracke (2007)

Note the pronounced decline in investment-to-GDP and real investment in the “internal” and “mixed” adjustment episodes. Now consider the trajectory of U.S. investment (in logs, total fixed in blue, nonresidential in red, residential in green).

Figure 1: Log real fixed investment (blue), nonresidential fixed investment (red), and residential investment (green), in billions of 2000Ch.$, SAAR. Source: BEA, NIPA, July 27 release.

Even with 07Q2, we already see deceleration in total fixed investment. Higher real interest rates for households (think of the jump in jumbo loan rates) and credit rationing (think of households that can no longer access credit) should mean further residential investment decline. To the extent that corporations are sitting on loads of cash, one shouldn’t expect a deceleration in investment; on the other hand, we’ve already heard about the puzzle of why business fixed investment is so low. I see no reason to expect a reversal of this phenomenon, given greater uncertainty about the future. And for smaller firms wherein financing heirarchy constraints are binding, a generalized slowdown in economic activity with further depress investment (by crimping cash-flow which drives their investment behavior).

So, investment decline wouldn’t have been the way in which I would have envisioned the adjustment in the U.S. trade balance (and I certainly wouldn’t have tapped it as a preferred outcome). But thinking about it more and more, it seems like a plausible scenario.

One is tempted to ask if this outcome is avoidable. With little information — we are early in the stages of the unfolding drama — it’s hard to say. But I’d say that much is already “cooked into the cake”, to the extent that you can’t go backwards in time and undo the distortions of the economy introduced by “looting” behavior (see Akerlof and Roemer). Greater prudential oversight in the past might have helped (alas, too much deregulatory zeal ruled that out); tighter regulation now will not mitigate the current problem. And while monetary policy can do much to avoid a liquidity or a banking crisis, it will have a much more difficult time spurring investment against the background of a big housing stock overhang (for residential), and an uncertain business outlook (for nonresidential). (We’ll skip fiscal, for the obvious reasons.)

I’m the first to admit this is sheer conjecture. Maybe the rest-of-the-world will remain buoyant, decoupling will occur, and rebalancing proceeds smoothly with a compression of consumption in the U.S. Then again, maybe not.

Technorati Tags: global saving glut,

investment drought,

investment,

housing,

subprime mortgages,

recession.

Ainda sobre a crise

Você não precisa ser austríaco para explicar a crise. Claro, o interessante é saber qual teoria gera proposições testáveis (sim, austríacos modernos usam econometria, como se pode notar nos mais recentes números da famosa Review of Austrian Ec…

with investment still booming in china and the oil-exporters (see the moscow and dubai skylines for evidence …) the term savings glut seems increasingly apt — tho there is a bit of heterogeneity. investment in emerging asia ex china (and i think ex india) hasn’t recovered from the crisis, but speaking of asia ex china and ex india is sort of like speaking of north america ex the united states …

But shouldn’t a slow down in the savings glut in be associated with a drop off in capital exports to the US?

Personally I’ve always thought the reason say China exported so much capital was simply a shortage of profitable domestic avenues of investment, even though of course they are still undertaking FCI at a massive rate (almost historically unprecedented rate).

And this mainly as a result of the large rural population still clinging to pre-capitalist farming methods and their previous exclusion to a degree from investment opportunites in the major multi-nationals and banks.

That’s why although there has been a slowing in the proportion of foreign capital exports, the actual amounts continue to rise and will do so for the forseeable future.

Indeed according to Haver.com “TIC Data Show Sizable Foreign Interest in US Securities Even Through June; Hong Kong, Russia & Brazilian Investors Major Buyers”;

“The US Treasury’s monthly “TIC” data were reported yesterday for June. They indicate that foreign interest in US capital markets remained strong with the same magnitude of net flows into the US as occurred in May, the record period. Foreign investors bought $148.6 billion of US securities compared with $163.7 billion in May and “just” $91.8 billion in June 2006.”

But could this be of interest in explaining the recent stock market decline/turbluence;

“Purchases of equities also decreased, from $42.0 billion in May to $28.8 billion.”

bsetser and bill_j: Absolutely, for now, there is little evidence of a diminishment of East Asian current account balances. But as US investment decreases (at least in this scenario) and the relative attractiveness of dollar denominated assets decline, the US may prove less of a draw. I don’t expect these events to play out for quarters, perhaps even years.

According to this model, it looks like the “external adjustment” would be the best outcome for the US.

What if, as in the case os Spain, there is not possibility of external adjustment through exchange rates changes because the country belongs to a monetary union? Is the internal adjustment the only possibility?

Speaking of moral hazard and perception (even if incorrect) of government backing, certainly there is an impression of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac being government-backed, or at least “too big to fail.” Certainly they’ve had their own problems with accounting issues and creative financing, too. Both Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke have made speeches calling for more regulation of the two in the past, with the way that they dominate the secondary market and the moral hazard that the public perception creates.

Those accounting problems go back quite a bit– Franklin Raines went back to Fannie Mae in 1999 after being director of the OMB for a few years under Clinton I believe, but accusations that risk and earnings were misstated look a little worse right now.

IM: Given that the US is a relatively closed economy, I suspect that the external adjustment path is less likely.

John Thacker: I think you’re looking at the wrong place, given that the problems have arisen outside of the portfolios of the two GSE’s you mention. Better I think to consider the fact that there was little prudential regulation of the type of financial institutions Paul Krugman described today.

menzie — a hard question (or two)

a) should banks be allowed to take risks off-balance sheet (various conduits and the like) that seem to jeapordize their balance sheet in bad states of the world. or, put differently, should banks be able to set up an off-balance sheet entity to borrow short and lend long (thru the increasingly opaque securities market) if they are also promising to supply liquidity to that entity in a crisis without setting aside a bit more capital than they do now?

b) more generally, should the types of financial institutions paul krugman describes be regulated more than they are now? entities that finance themselves in the money market (think big deposits, i.e, securitized, to be sure, but s-term) to take on credit risk seem to have become systemic, so they are compelling government intervention to help them out — at a very macro level — to help reduce the risk that the system will seize up, but they aren’t subject to any real limits on the type of risks that they can take …

if i have framed these questions incorrectly do tell — i am curious. i cannot quite get my head around the policy implications of all this.

bsetser: Excellent questions, and ones which I — as a non-finance type — am reluctant to address in detail. As I watch commentators on CNBC demand the Fed drop the Fed Funds target rate, or the Discount rate to equal the Fed Funds rate, I am struck by how much interest the government has in managing the systemic risk associated with the decisions undertaken by the financial sector. So, on the second question, I think I have an answer of yes. How greater regulation — or just plain monitoring of the financial sector — might be implemented, I don’t know.

A first step would be for legislators and the executive branch to agree that more monitoring needs to be funded. Getting rid of a mind-set that always settles on a market-knows-best mentality would be useful, as well.

On the technical question of whether there needs to be greater regulation of the off-balance sheet aspects of banking activities, I think the answer is a prima facie yes, as well.

i expect a reverse conundrum.Housing market crisis motivates the consumer to retrench.The trade balance improves as the econoy slows but interest rates in belly of curve stay stubbornly high in spite of serial fed rate cuts.The lack of consuner spending cuts the available pool of spendable greenbacks at the foreign central banks and there is a significntly reduced demand for US assets as the dollars aint there to invest!! the reverse conundrum! JJJ

given that the problems have arisen outside of the portfolios of the two GSE’s you mention

Surely you don’t mean to suggest that all of the problematic subprime and other loans were jumbo loans? Granted that most of the problems have been in areas with much higher real estate values, but I still find that a bit much.

So then we find that the worst affected people are apparently: getting jumbo subprime loans for houses bought in a narrow span of years at the height of the bubble or possibly got home equity loans during that time. Presumably we’re also talking about homes less than $1 million and people who didn’t know ahead of time that they would be affected by the AMT, since the mortgage interest deduction in particular encourages people to leverage more and stay in debt on their house.

I know some people with subprime mortgages who did very well, because they bought earlier in the bubble. It’s very easy to say that prices were going to go down eventually, but even people who believed that were still buying, hoping to flip to the greater fool. I’m fairly unconvinced that more regulation would have stopped the bubble; it would have simply meant that people with worse credit wouldn’t have been able to participate, helping some and hurting others.

(Personal disclosure: I personally rented when I came to the DC area a year and a half ago, because I felt that renting was much cheaper than buying and something was going to give one way or the other first, so perhaps I don’t have as much sympathy for people I saw buying houses hoping to make huge profits flipping them as the bubble continued as I should.)