Some analysts, and perhaps the market, seemed to view Friday’s cut in the Federal Reserve discount rate as a first step in lowering interest rates generally. That view may prove to be correct, though I’m inclined to look first for an explanation in terms of the narrow tactical challenges of managing current liquidity needs.

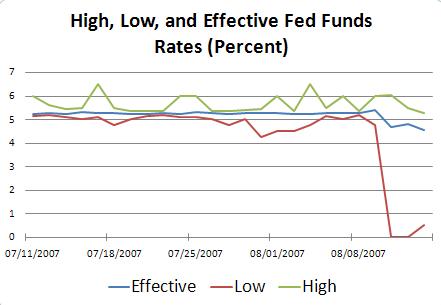

Unlike many other central banks, the U.S. Federal Reserve does not directly control its primary policy target, the federal funds rate. Instead, as I described in more detail last week, the Fed makes daily changes in the volume of outstanding Federal Reserve deposits in a way that it expects to be consistent with its objective of achieving a particular value for the rate at which these deposits are lent overnight from one institution to another on the federal funds market. Their objective is defined in terms of a volume-weighted average of all the transactions during the day (referred to as the “effective” fed funds rate), with the target for the effective rate currently declared to be 5.25%. The Fed usually makes at most one such intervention early in the day, and is then content to allow the actual fed funds rate at which banks choose to borrow or lend to each other fluctuate above or below the target. Often at the end of the day, and especially on the last day of the two-week period in which banks have to complete the satisfaction of their required average holdings of reserves, one will see the fed funds rate spike up, if some bank finds itself unexpectedly needing funds at a time when everybody else is finished trading for the day, or fall to practically zero, if some bank unexpectedly finds itself with excess funds that nobody else is interested in borrowing. As William Polley noted, this last week these intraday fluctuations have been particularly dramatic, with one trade last Wednesday (a settlement day) as high as 6% and another on the same day for only 0.25%.

|

Why does the Fed allow so much intra-day variability in the interest rate it is intending to target? One reason is that the Fed does not want to be in a position of subsidizing individual banks that choose to make unusually risky investments. If a bank knew that, no matter what it did, it could always obtain an unlimited source of funds at a 5.25% rate, the bank would have an incentive to borrow a huge quantity of such funds and use them to make higher yielding, but potentially quite risky, investments. If instead the bank must rely on a competitive lending market for its overnight funds, it knows that the more it tries to borrow and the riskier its portfolio becomes, it will have to pay a higher rate to borrow those overnight funds than will another bank with a more solid balance sheet. The Fed intentionally allows different banks, in different circumstances or at different times of the day, to pay a higher or lower rate for fed funds than do other banks, as one way of making sure that banks face immediate consequences of any extra risk-taking.

In addition to choosing a particular target value it hopes to see for the effective fed funds rate each day, the Fed has a strong intention to prevent a full-blown liquidity crisis of the type that was seen relatively frequently in the nineteenth century, but have been successfully avoided in the United States since the founding of the Federal Reserve in 1913. I am using the term “liquidity crisis” here in a narrow and precise sense to refer to a situation in which the value of banks’ assets would be more than sufficient to pay off all their customers and creditors if these assets could be sold off in an orderly market, but may be insufficient if those assets must be immediately liquidated at fire-sale prices. Such episodes have been avoided since 1913 because the Fed stands ready to play the role of a lender of last resort, offering to create reserves in whatever quantity may be necessary to ensure an orderly liquidation of assets.

Of course, there is an inherent tension between the goals of serving as lender of last resort and making sure that banks are disciplined for risky behavior, and this tension is at the heart of the current policy dilemma facing the Fed. To help to achieve these twin objectives, the Fed has a separate tool, the discount window, through which it offers to lend directly to banks, temporarily giving them newly created reserves while holding high-quality assets as collateral for such loans. Again there have to be some institutional checks to prevent excessive risk-taking for banks using this facility. Historically, the Fed achieved this by placing additional limitations and regulatory oversight on banks that borrowed too much or too frequently at the discount window. Partly as a result of these, the discount window acquired a certain stigma, where many banks chose to pay even an arbitrarily high fed funds rate rather than try to borrow anything directly from the Fed itself.

In January 2003, the Fed decided to change this practice, declaring an end to the administrative restrictions on discount window borrowing, allowing and even encouraging banks to borrow as much as they wanted from the discount window. What was supposed to prevent banks from abusing this privilege was the fact that the discount borrowing rate was set at a value 100 basis points above the fed funds target. The idea was that the system could automatically put a ceiling on the effects of any short-run liquidity crunch, while ensuring that any bank that routinely acquired its funds from the discount window would be at a strong competitive disadvantage relative to banks that simply used the fed funds market.

We had the first real test of this new system August 10, when the Fed was worried about the possibility of an unfolding liquidity event, if not actual crisis. This was associated with a significant volume of offers to borrow fed funds at 6%, which would be 75 basis points above the Fed’s current 5.25% fed funds target, but 25 basis points below its 6.25% discount rate. Not surprisingly, banks would prefer to borrow at 6% from another bank rather than pay 6.25% to the Fed. Of the $18.5 billion increase in the average level of Federal Reserve deposits over the week ended August 15, only $20 million came from increased discount window borrowing, and total average discount window borrowing remained a quite modest $271 million.

I think that the Fed would prefer to rely on the automatic functioning of the discount window, rather than the multiple aggressive open market operations that we saw on August 10, to respond to the kind of challenges that have arisen in markets over the last few weeks. If the Fed really wants banks to go to the discount window rather than bid the fed funds rate up to 6% in response to these kinds of pressures, it makes sense to offer to lend through the discount window at the new lower rate of 5.75%, as well as extend the terms of these loans to 30 days, as the Fed did this Friday.

I believe that the Fed adjusted the discount rate rather than the target fed funds rate not because it’s a back-door way to lower interest rates, but instead in order to address the specific policy objective of making sure the discount window gets used as part of the automatic response to the kinds of liquidity pressures that have been bobbing up these last two weeks.

Now, it may well be that they separately later decide that a lower target fed funds rate also makes sense in the current situation. Indeed, I was on record urging the Fed to cut the fed funds target, and predicting that they would indeed choose to do so, well before the excitement of the last two weeks. It’s just that now I seem to have a lot more company in that advice and prediction.

Nevertheless, I believe that in changing the discount rate while holding the fed funds target constant for now, the Fed did exactly what it wanted to do, rather than some kind of half-way measure with another objective in mind.

Though if you want some other opinions, check out Econocator, Mark Thoma, King Banian, or the always-excellent Tim Duy.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

liquidity crisis,

Federal Reserve

The Fed’s action to lower the discount rate is simultaneously very targeted and very general. Late last week, Countrywide was gasping for cash because the mortgage security trading markets had stopped functioning. Countrywide provides some large percent (around 15%, if memory is near correct) of mortgages in the US. Countrywide pulled in their entire $11.5 billion loan arrangement to get cash. By lowering the discount rate, the Fed signaled, in a targeted way, that they would stand behind banks who need cash. That relieved some tension among banks, which would affect their trading behavior. Since the discount rate is so seldomly changed, the Fed got a lot of press coverage on a rate that sees little traffic volume, i.e., has little impact in normal situations. That was the broad and general signal. It relieved some tension in the broad investor public. And the Fed didn’t have to touch the Fed Funds rate, which would affect the value of the US dollar in FX trading.

Whether this action is sufficient is a whole different question, and remains to be seen. But as a quick, cheap tactical move, it was effective for at least a few days – maybe lots longer. We shall see.

Thanks for the clear explanation of the discount rate and how the discount window works.

Do we have to know this for the test?

Nah, Joseph, you earn your degree here just by showing up.

This is the most clear explanation I’ve ever read on the topic. Kudos.

JDH — would you say that a good measure of this move’s success would be whether over this maintenance period the Fed Funds (High-Low) spread stays small during the whole two weeks, as opposed to varying quite a bit as it did for the period ending 8-15?

Seth, I would think the key measure of success would be whether discount window borrowing increases and reserves supplied by open market operations decrease.

Mike Laird – I’ve been thinking the same thing RE: Countrywide, though their market share is closer to 20% than 15% . . . . I would note that Countrywide is a much more of a wholesaler rather than retailer, so given the sudden gross overcapacity of the mortgage industry you could take Countrywide out back and shoot it and put it out of its misery and it wouldn’t be missed – the independent retail mortgage folks could still get wholesale loans from other parties and the industry wouldn’t miss a beat . . . . . to some extent the skeptic who said Countrywide’s most valuable asset was “their toner inventory” wasn’t too far off.

I would add an additional note, however. If you are an overleveraged hedge fund operator or non-regulated financial institution with a liquidity problem and lots of illiquid mortgage securities you can’t sell AND without access to the discount window, you can still take your illiquid mortgage securities to your preferred bank or investment bank and for a modest fee have THEM get your securities repo’d for you at the discount window.

That’s still a good thing, and an example of how well Bernanke’s targeted move addresses the liquidity problem in the markets. However. Because there’s a psychological aspect to the credit crunch and events continue to snowball out of control, the elegantly targeted mathematics of the solution are grossly insufficient to stem the carnage. My two cent’s worth: If the Fed doesn’t cut the FF rate this week, (1) by September they’ll really, really wish they had and (2) an ugly disaster in the markets will force them to cut FF BEFORE the next FOMC meeting anyway.

If you want one, single factor to watch, just keep your eye on Countrywide’s stock price.

PS: I’d be betting dollars-to-donuts (as one of my old structural engineering prof’s used to say) that Warren Buffett will NOT end up buying Countrywide Financial . . . . . . Buffett already has major exposure to Countrywide competitors Wells Fargo and Bank of America, and the uglier Countrywide’s demise the more those two investments of Buffett’s BENEFIT. And as primarily a wholesaler of mortgages, Countrywide doesn’t have much of value to an acquirer.

Buffett might, maybe, buy a piece of Countrywide on the cheap, but how does that help “Sunny” Mozilo get out of his fix? Sell Buffett your best asset(s) for cheap? Better to just take mortgage paper to the discount window for cash, IMHO.

A question for anyone who knows the answer:

After the discount rate was cut 50 bp the discount/fed funds targe rate is now also at 50 bp (down from the standard 100 bp). If indeed the Fed decides to lower rates at the next FOMC meeting will the discount rate drop as well keeping the spread at 50 bp or will the discount rate stay constant increasing the spread to 75 bp (or whatever it is post rate cut). If the spread increases to 75 bp (i.e. discount rate stays at 5.75) would that influence the effectiveness of a target rate cut?

Sorry that first sentance should read the discount/fed funds target rate SPREAD is now at 50 bp.

The problem seems not the bank has not enough money, but they are unwilling to lend. The bank now has problem in evaluating the value of borrowers’ collateral. In this case, the borrowers may be other banks. A drop in discount rate seems not helpful.

I would assume that the fed hopes that lowering the discount rate will encourage banks to lend more to non-MBS or CDO (like the high quality commercial papers or real investment firms), but this action needs to assume the fed know more than the banks themselves on the quality of different loans.

Professor,

Very nice piece. Thanks.

A minor issue: as I understand, assets serving as collaterals for discount window borrowing don’t have to be high quality — the amount of loan will be adjusted according to the quality of the collateral (hair-cut). Therefore, subprime mortgages can be used as collaterals, I think. (In contrast, open market operation only takes agency backed mortgages as collaterals.)

On a separate issue, do you have any explanations why the very short term treasury rates have dropped so much in the past few days? Right now, 6-month and 2-year treasuries yield about 4 percent, 3-month treasury less than 3 percent, and 4-week treasury less than 2 percent!

Very good analysis of how the fed is trying to walk a tightrope between providing sufficient liquidity to enable the system to function without flooding the system with too much liquidity and funding an inflationary reaction on down the road.

Finally, you are right to stress that it is too early to tell how it will work. On this basis a flat stock market rather than a soaring stock market may be a sign that the Fed is doing a good job of balancing these two points.

Pat, regarding your question about the swift drop in short term T bills. Many people have recently discovered that about 40% of commercial paper is backed by some mortgage security. Commercial paper is a short term security and is owned by “everybody” – pensions, money market funds, corporations, banks, you name it. Some of these folks have decided to liquidate their commercial paper holdings that are backed by mortgages. So what do they buy that is safe – short term treasury bills. Hence, the bill rates dropped sharply. This strikes me as a panic over-reaction, and we’ll likely see T bill rates go back up to about where they were. The bill rates started back up today.

Mike Laird,

Thanks for the explanation. Do you mean that people who bought ABCP did not know what assets were backing the paper until just recently? That is quite amazing. I can understand some investors had no clue what were behind the CDOs, but not knowing what assets were behind the ABCP seems another level of ignorance, no?

Talking about volatility: 4-week T-bill closed above 3 percent!

Professor Hamilton,

Since another poster kept on bringing up repo at the discount window, could you confirm whether discount window borrowing is unsecured (my understanding)?

HZ, according to the Fed’s website, “All Discount Window advances must be secured by collateral acceptable to the Reserve Bank.”

Thanks!