In glancing at Table 4 the last issue of the Economist (sub. req.), I was surprised that so many countries had downward sloping yield curves. Should we worry?

Out of the 33 economies listed in the print edition, 18 have 10 year interest rates lower than the 3 month rate (I count the euro area as one economy; the proportion would be higher if one counted the individual countries).

More significantly, while the US 10 year/3 month spread is now positive, that in the euro area is now negative. Figure 1 shows the spreads as cited in the Economist, using data from 10/10/06 and 10/11/07.

Figure 1: Ten year benchmark bond yield minus three month yield spreads, from Economist, Oct. 12, 2007 and Oct. 11, 2006 issues, and author’s calculations.

So back to the question of whether one should worry (about widespread recession). Referring to Table 4 in the Economist, one sees that many of the negative term premia are in emerging markets. It’s not clear that the standard arguments for why the yield curve predicts economic activity pertains to these economies (see this ECB working paper [pdf]).

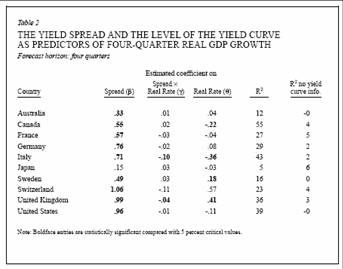

On the other hand, Kozicki (1997) points out substantial predictive power for certain cases — when the level of the real short term interest rate is included and interacted with the spread.

Table 2 from Kozicki, “Predicting Real Growth and Inflation

With the Yield Spread,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, 1997Q4.

This means there is some predictive power of term spreads. For Canada, with a positive spread, these estimates imply continued growth. Similarly for Sweden and Switzerland. For Japan, the positive spread is essentially not informative. For Australia and the UK, the negative spread suggests a slowdown.

Now, the newest development is the shift to negative of the yield curve in the euro area. This is shown in Figure 2. According the results in Kozicki’s Table 2, the negative sread bodes ill for growth, although it might be that the recent spreads are distorted by the effects of the credit crunch.

Figure 2: Ten year minus three month term premium, daily averages. For US (blue), ten year rate is constant maturity, three month rate is for T-bills in secondary market; for Euro area (red), the ten year rate is the GDP-weighted rate of on-the-run benchmark bond yield, three month rate is for interbank money rate. NBER recession dates shaded gray. Sources: St. Louis Fed FREDII; IMF, International Financial Statistics; NBER; and author’s calculations.

As I noted in a previous post, the euro yield curve matches the German yield curve, which predicted the last recession in the euro area. This means that the yield curve is signalling the same message as that provided by other indicators (e.g., September 28 Eurocoin).

The answer then to the question posed in the title is a strong “maybe”.

Technorati Tags: recession,

yield curve,

euro area,

and

term spread.

There is a time-honoured British expression, “I don’t give a flying fart in space.”

Well, someone (or someONES) simply do not give a flying fart in space with respect to either the reality or the prospect of inflation. Hence the demand for long paper at rates that are hardly protective.

The controlling “bets” seem to be on the side of the belief that the entire global “house of cards” will just fly apart.

Thus we have the seemingly permanent “conundrum.”

A conundrum here, a conundrum there, pretty soon you’ve reached “the long run.”

There is some forecasting value to a negatively sloped yield curve. But like all forecasting rules it is not perfect and sometimes gives false signals.

A negatively sloped yield curve use to be a great stock market sell signal — markets almost always fell when the yield curve was negative.

But this has not worked in recent years. If a negatively sloped yield curve is not correctly calling a bear market I suspect you should not give much credence to its forecast of a recession.

One of the consequences of the “great moderation” is that recessions are less likely. Should this imply that a negatively sloped yield curve has less forecasting power?

The US economy just went through a mini inventory correction over the past year, so it is hard to believe that a new, major inventory correction is on the immediate horizon. This is a part of the new great moderation world.

Menzie,

Thanks for this international perspective. It is something that most do not recognize.

Spencer,

I agree. Today the yield curve seems to be more about inflation expectations than recession. In the past a negative yield curve reflected downward pressure on interest rates in the future because of reduced business activity. This is a point Art Laffer made about the US inverted yield curve in the early years of this century. Today the inverted yield curve is more a reflection of the market’s assessment of the monetary authority’s willingness to control inflation. On this point the US is getting a vote of more inflation.

The yield curves are different today because so many central banks are buying long-term debt with their freshly created Yuan, Yen, etc. They do not express what they did in the past.

I thank Menzie for bringing up this topic. The inverted yield curve and ~117 yen to the dollar are the two things that I don’t get about the current economy.

I wonder if algernon is on to something.

I think it’s important to recall that the long term/short term spread is, depending upon the theory, a mixture inflation expectations, a term (risk) premium, and demand/supply for credit factors.

Inflation expectations could be heading up even as demand for credit is falling, so that the net effect is small movements in either direction.

I think the idea of central banks buying long term securities is part of the reason that U.S. long term yields might be lower, but it doesn’t seem to be a particularly good explanation for why non-U.S. spreads are declining in Europe. An argument based on pension funds is more plausible.

It is my impression that PBoC buys long-term European debt to counter Yuan appreciation against the Euro. And that Yen carry traders buy long-term debt. What are Petro-state recyclers buying to prevent their currencies from appreciating? Don’t think it’s 3-month notes somehow.

Hi, you might have a gander at the Vox column by Charles Goodhart on VoxEU.org. In a nutshell:

“Recent research suggests that the additional predictive power of the yield curve beyond the information in other macroeconomic variables often appeared during periods of uncertainty about the underlying monetary regime. This is true, for example, of the US during the Volcker disinflation episode.”

Can you look at world quality spreads in the same way?

I’m more worried about the consequences of quality spreads widening then yield spreads.

Richard Baldwin: Excellent suggestion. I think this is an interesting point, and provides an interesting counter-point to the recent literature explaining the conundrum as a function of reduced uncertainty regarding the conduct of monetary policy. The subprime mortgage mess may have upset this (short-lived) reduction in uncertainty.

spencer: I don’t have access to these spreads on a consistent basis, but you can see some of them in Figure 1.9 of the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report. Not a pretty picture.

Menzie,

Good work, yes Algernon is on to something, its called the carry trade.

and Menzie is correct regarding pension funds matching assets to liabilities.

Risk premiums have been unrealistically low, but thats changing as the pendulum swings the other way. Just look at libor.

Said market reaction is turning the borrow short buy long model upside down and shaking it.

The unwind drops longs and pulls up the shorts. Squeezing the cajones of those involved just a little tighter.

One thing I do know, if that situation ever makes it from “table 4” to the COVER of the Economist, the yield curves will all be sloping UP inside a month.