I used to wonder about the use of this term a lot, at least in the context of government pronouncements. Here’s my answer. First, the use of the term in context. From Bloomberg:

Weak Dollar Boosts Growth Without Fueling Inflation (Update1)

By Matthew Benjamin and Vivien Lou Chen

Oct. 8 (Bloomberg) — Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, whose signature appears on every new dollar bill, may find the weak currency with his name on it helps the U.S. economy more than the strong one he publicly endorses.

The dollar’s 8 percent slide during Paulson’s 15 months in office is good news on the docks of Long Beach, California, where shipping containers are making their return trip to Asia filled with U.S.-made computer, auto and aircraft parts whose prices have become more competitive abroad. What’s more, economists don’t foresee the weaker currency generating higher import prices and accelerating inflation.

“The dollar is in a quasi-sweet spot,” says Joseph Quinlan, chief market strategist at Bank of America Corp. in Charlotte, North Carolina. “It’s dropped enough that it’s creating an earnings upside for U.S. multinationals, while I expect many foreign companies to hold the line on prices they charge U.S. consumers.”

Exports by General Motors Corp., Boeing Co. and other U.S. companies were up 11 percent in the second quarter from a year earlier, shrinking the nation’s trade deficit in goods for the first half by $14 billion, to $405 billion, and helping the economy weather the housing bust.

According to estimates by Goldman Sachs Group Inc., that’s the biggest improvement in 20 years; exports of goods grew more than twice as fast as imports in the first half of 2007.

Further Narrowing

The government will report August trade figures on Oct. 11, and a Bloomberg survey of economists says they will show a further narrowing of the gap.

Asked how Paulson, 61, views the dollar’s recent slide, his spokeswoman, Brookly McLaughlin, refers to recent statements from him that reiterate the official U.S. policy since Robert Rubin ran the Treasury under President Bill Clinton: “I feel very strongly that a strong dollar is in our nation’s interest.”

As Treasury secretary, he can’t be expected to say anything else, says Tom Fitzpatrick, global head of currency strategy at Citigroup Inc. in New York.

“The U.S. needs external capital to fund its deficits,” he says. “So you have to say a strong currency is in your interest, because if you go the other way, why the hell would anyone want to invest here?”

At the same time, Paulson has good reason to be privately pleased with the dollar’s decline, says Sophia Drossos, currency strategist at Morgan Stanley in New York and a former Federal Reserve economist.

Protectionist Pressures

Noting that Congress is considering sanctions to redress the trade imbalance with China, she says, “If you are the U.S. administration and you don’t want to see protectionism take hold, what is your incentive to change anything? It doesn’t seem like it’s in the interest of the U.S. Treasury to arrest the decline of the dollar. They are accepting it as a move based on fundamentals.”

The impact of the dollar’s weakness is evident at the port of Long Beach — the nation’s second-busiest behind Los Angeles — where exports jumped 34 percent in August from a year earlier.

Larry Cottrill, the port’s director of master planning, says the number of unfilled containers leaving the port dropped 14.5 percent in August and was down 4.5 percent for first 11 months of the year ended Sept. 30. That’s a turnaround from the last decade, when the fastest-growing container category was outbound empties, he says.

…

Shifting Production

Rainer Schmueckle, chief operating officer at Daimler AG’s Mercedes Car Group, said at a Sept. 25 press conference that the Stuttgart, Germany-based company would have to consider shifting more of its production to the United States if the euro, were to rise above $1.45 and remain there. The euro traded at $1.4092 at 8:42 a.m. in New York.

…

What I think is interesting about this quote is that it highlights two different meanings of the idea of dollar strength. The first is the level of the dollar, adjusted for price levels. This is sometimes referred to as price competitiveness, and can be measured by the trade weighted value of the dollar after adjustment by the CPI (as in the the Fed’s index) or unit labor costs (as in the IMF’s series reu).

But Tom Fitzpatrick’s quote refers to a second (and in my mind confusing) use of the “strong dollar” term. Here he is referring to the returns on dollar assets denominated in a common currency. So consider the expected return on dollar assets:

i US – i EU – E[d(s)]

Where i US is the interest rate on dollar asset, i EU is the interest rate on euro asset, and E[d(s)] is the expected rate of dollar depreciation against the euro over the horizon consistent with the maturity of the debt instruments. The greater the anticipated depreciation, the lower the expected return in dollar terms on dollar assets, holding all else constant. To the extent that uncovered interest parity does not hold (see [1] [pdf] for definitions, [2] and [3] for discussion), one might think that the as this term declines, capital inflows decline (admittedly, this is an old fashioned view, but as far as I can tell, this is how economists in the financial sector and practitioners talk, to a first approximation).

So, since a weaker dollar at a given instant is a plus to the extent that it encourages expenditure switching, we don’t want a strong dollar. But to the extent that expectations regarding further weakening over time of the dollar tend to diminish capital inflows, we prefer a “strong dollar” (at least if we want to finance the ongoing incipient current account imbalance).

What do exchange rate forecasts — in this case from Deutsche Bank — indicate? They indicate substantial dollar weakness in the next three months, with recovery in the subsequent months.

Figure 1: Spot exchange rate, monthly average (blue line), end of month (blue triangle), Deutsche Bank forecast of 5 October (red circle) and forwards (green asterisks). Source: St. Louis Fed FRED II, and Deutsche Bank, Exchange Rate Perspectives, 27 September 2007.

But of course, these are merely forecasts, and as any expert will allow, forecasting exchange rates is notoriously difficult. One particular worry is highlighted by Figure 1. The dollar has been declining fairly steadily against the euro over an extended period (and is forecasted to depreciate about 11% on an annualized basis over the next quarter). Should this trend become ingrained into market expectations, the DB forecasts could be proven very wrong, and the dollar become even weaker than anticipated over the longer horizon of a year. In the absence of any countervailing effects (i.e., invoking the ceteris paribus condition), the US interest rate would have to rise, Euro rate decline, or capital flows decline drastically. This is the worry I’ve laid out in the past here, but thankfully has failed to become a reality.

However, a floor on the dollar/euro exchange rate may be introduced by movements in euro area interest rates — with softening growth in the euro area, the ECB is more likely to drop interest rates. (Calls for intervention would likely go unheeded, and in any case, the effectiveness of forex intervention is debatable.)

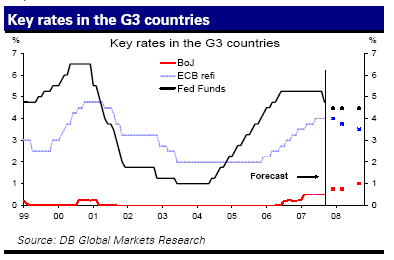

Figure 2: Actual and forecasted policy rates in US, Euro area, and Japan. Source: Deutsche Bank, Global Economic Perspectives, 8 October 2007.

So, we may get a “strong dollar”, in at least the second sense, as policy rates in the euro area and Japan rise, and the Fed Funds rate stabilizes. (Of course, this is view is predicated on the continued “containment” of the housing/subprime mortgage turmoil, and no more surprises — a la Jim’s recent post.)

Technorati Tags: dollar,

euro,

intervention,

interest rate parity

I think the quote by Tom Fitzpatrick refers specifically to the expectations term. That is, “a strong dollar” refers to the (anticipated future) level of the dollar relative to its current level. Then the only difference between the two usages is what is used for comparison: in the first usage, it is the level of the dollar relative to perhaps some notion purchasing power parity; in the second usage, it is the level relative to the current level. And even that I’m not sure is a real difference: when Secy. Paulson says he wants a strong dollar, he could just as well mean “strong relative to purchasing power parity”, and as long as investors believe him and have confidence in his ability to realize that preference, they will not expect the value of the dollar to decline.

I think, though, that there’s something fundamentally wrong with discussing this (as Tom Fitzpatrick does) in terms of the need to attract foreign capital to fund deficits. In practice, the capital that the US has attracted this decade mostly went to finance a housing boom. Granted, it also reduced the government’s interest cost, but I think that’s a secondary consideration.

The alternative to attracting capital is to have higher interest rates and shift resources (theoretically) out of investment (thus far mostly residential housing investment) into exports and into producing domestically that which we would otherwise import. That alternative doesn’t sound so bad to me. While I do favor investment in plant and equipment, I’m not sure it would really be damaged much by higher interest rates accompanied by a lower dollar, because I think there might be a better investment accelerator effect from trade-related demand than from housing-related demand. Moreover, the low interest rates seem to have had the side effect of raising consumption, perhaps by generating a lot of home equity that resulted in relaxed liquidity constraints. If higher interest rates reversed that effect, then investment wouldn’t have to decline.

And the previous paragraph assumes full employment, but in practice we don’t really know where full employment is located. A weaker dollar might have the effect of allowing the US to discover that the NAIRU is lower than we thought, in which case higher interest rates might not even be necessary.

Let me restate my objection to Tom Fitzpatrick a bit differently. Since international capital markets are quite efficient, they will see to it that the US attracts exactly as much capital as it needs to finance its deficits, and they will do so with or without help from Secy. Paulson’s jawboning. There are two mechanisms by which the market will assure sufficient capital: (1) dollar interest rates will rise to make investment in the US more attractive, and (2) the value of the dollar will fall precipitously until there is no longer any anticipated depreciation (or until the anticipated depreciation is sufficiently small, or until appreciation is anticipated i.e. an “overshoot”), so that dollar-denominated investments will once again be attractive at any given interest rate. I expect the second mechanism to be more important. By talking up the dollar, Secy. Paulson, rather than “attracting investment,” is interfering with the mechanism by which the market would attract investment. And the result will be that the ultimately required drop will be even more precipitous.

Opening Bell: 10.9.07

Sonepar Offers to Buy Hagemeyer for EU2.51 Billion Biiiiig consolidation in the electronic sockets and switches market, as France’s Sonepar SA has made an offer for Hagemeyer NV, based in the Netherlands. If the deal goes through, Sonepar would…

A strong currency to the electorate means a stable currency, but to most economists it means an appreciating currency. Paulson is making a political statement to reassure the public that the administration is not inflationist.

Now Fitzpatrick states, “…you have to say a strong currency is in your interest, because if you go the other way, why the hell would anyone want to invest here?” Fitzpatrick is implying that interest rates don’t matter very much if your currency is a failure. To understand this let me ask you what interest rate would intice you to invest in Zimababwe bonds?

Unless one really understands what a strong or weak currency is they make such foolish statements as those of Benjamin and Chen, Weak Dollar Boosts Growth Without Fueling Inflation. The very definition of a weak dollar implies inflation, a weak currency is a currency that is losing value. Now inflating the dollar may give a short term increase in imports, but it is at the expense of the citizens as their currency deflates and, as in the example of Zimbabwe, inflation will in time actually stop investment in your country no matter what your interest rate.

Too may economists are near-sighted today looking at the short term effects on a narrow segment of changes in the value of a currency. (Where is Economics In One Lesson when you need it?) Changes in the value of the currency always create friction in the economy and a resulting loss of wealth. Government (or quasi-goverment) induced change in the value of the currency is always damaging to an economy whether the result is a “weaker” currency or a “stronger” currency.

What is sad is that the dollar is the world reserve currency and so the gyrations of the dollar effect the entire world. That means every time the dollar becomes weaker or stronger the impact is not isolated to the US but the friction is felt throughout the whole world. What might be a small loss of wealth in one country becomes a huge loss of wealth throughout the world sometimes even bringing down governments in smaller countries.

DickF, the dollar came fell dramatically from early 1985 to late 1987 but that “inflation” didn’t show up in US price indexes.

knzn,

I don’t normally use the CPI to measure inflation because it is a lagging indicator and the “basket” changes with the whims of the government but to address your point.

CPI 01/01/85 105.7

CPI 12/01/87 115.6

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/data/CPIAUCSL.txt

Looks like 9.4% inflation over two years to me.

But understand that there is a lot in the numbers that “measure” inflation that mask the actual value of the currency, not the least of which, the Reagan tax cuts.

Dick,

That is (almost) 3 years, not two. Doing a rough average that is around 3% per year.

nobody,

You are right.

Take a look at the data and you will see a steady rise in CPI all the way up to today. Inflation does not change prices all at once. Prices move slowly as the inflation works through the system. Because of long term contracts it may take 20 years for some changes. Of course as there is less and less confidence in the dollar it becomes more and more difficult to find long term loans.

Note that the CPI continued to rise even during the recession of 1981-82. Also note that the CPI has roughly doubled since the end of that recession. This is during a period when many claim the currency was stable – a doubling is stable! It is interesting that though most of the 19th and 20th century inflation was essentially zero.

The creation of the FED started the monetary problems that have plagued us ever since with more or less pain. The FED is perhaps the biggest failure of any government institution and yet it persists and keeps gaining power.

Fed has made the asset-poor, dollar-salary-earning Joe even poorer.

Asset hyperinflation has passed him by.. his main asset (house) could be in free fall//

Thanks maestro.

In Euro terms – as Euro is a better “international” currency now – Joe’s salary has tumbled ~50% since 02.

Good deal, HeliBen!

This is during a period when many claim the currency was stable – a doubling is stable! It is interesting that though most of the 19th and 20th century inflation was essentially zero.

Average inflation may have been essentially zero, but there were wild up and down swings, alternating bouts of inflation and deflation. This kind of unpredictable price behavior is more harmful to economic activity than a low, steady inflation rate.

knzn: Thanks for the thoughtful comments. I think you are right that in applauding the strong dollar, Paulson is referring to expected depreciation, rather than the price adjusted level.

However, I’m not certain I agree that the international financial markets are efficient, in either the technical (Fama) sense, or the more general sense of always allocating capital to where it receives the highest risk adjusted returns. In the former sense, the commonplace rejection of the unbiasedness proposition (the joint hypothesis of uncovered interest parity and rational expectations) gives one pause for thought. In the latter, the inability to identify empirical determinants of the exchange risk premium (related to the first view) is troubling for those who believe in fully efficient international capital markets.

I just meant efficient in the sense that the quantity of capital supplied will equal the quantity demanded, so there is no way that the US could fail to attract enough capital to finance its deficits. (Technically, I suppose “liquid” would be a better word than “efficient”.) My point is that, to talk about the issue meaningfully, one has to talk mostly about prices (interest rates and exchange rates) rather than quantities. When someone says the US needs to attract capital, the substance of that statement is that, for some unspecified reason, we prefer an equilibrium in which the interest rate is lower. And one also has to have an argument as to why the interest rate, rather than the exchange rate, would do the adjusting.

nobody,

I do not consider the Great Depression and the Great Inflation to be “a low, steady inflation rate” but even at that even since 1980s the currency has had huge gyrations. The reason you do not see them is because of the indicators that are used. The decline in 1987 was a huge decline and it led to the near total destruction of the oil business in Texas. The deflation of the mid-1990s again brought destruction to the oil industry pushing prices below production and causing may well to be capped causing much of the current high oil prices and production problems.

And right now if taxes are raised and the FED doesn’t make some drastic changes to the weak dollar, we will see a return of chronic inflation in about 2 years. Will we have another Reagan/Volker to pull us out of the fire? I certainly hope so.

knzn: I agree. Although, as we can see from recent events in the asset backed corporate paper market, sometimes prices can’t do all the adjustment, and quantities adjust discretely. In the international finance literature, this phenomenon is called a “sudden stop” — admittedly something I don’t think likely for the U.S. or any other country with a well developed financial market and tax system, and a floating rate. But who would’ve guessed that CDO’s would be so illiquid?

I know nothing about currency strength. But do have a question Is the US dollar considered strong or weak in relation to the Euro and the Pound Sterling at its current rate of 2.03

1) DickF is dead-on. How “brilliant” do you have to be to say something like, “Weak Dollar Boost Growth Without Fueling Inflation”?

2) Does ANY other reputable central bank engage in remotely comparable selection to the Fed’s measures of inflation ex-food, ex-energy, and de facto ex-housing? (Does it exclude healthcare and education as well?)

3) Can anyone tell me of any items usually excluded from the core CPI basket that have *deflated* over the past five years?

I can understand reasons for a moderate weakening of the dollar. I believe Bernanke sees the United States in a position analogous to Great Britain in 1927, with a high trade deficit and persistently overvalued currency. And instead of allowing the Chinese (=US in 1927) to perpetuate a system which will otherwise end violently, Bernanke is turning the screws on the Chinese (who are politically unable to revalue the yuan themselves) until domestic inflation scares them more than millions of lost exporter jobs.

But having said that, the Fed is going overboard. The dollar has lost enormous international credibility during Bernanke’s tenure. In terms of gold, euros, or any other major currency, US assets have been in recession for quite some time and inflation is WAY higher than what official figures state. No that isn’t quite a fair comparison, but it’s a very, very different universe from the one that Bernanke and Mishkin live in.