As the dollar continues its decline, I think it’s useful to step away from the high frequency analysis [1],[2], to consider what the currents in academic thinking on the enterprise of predicting exchange rates are.

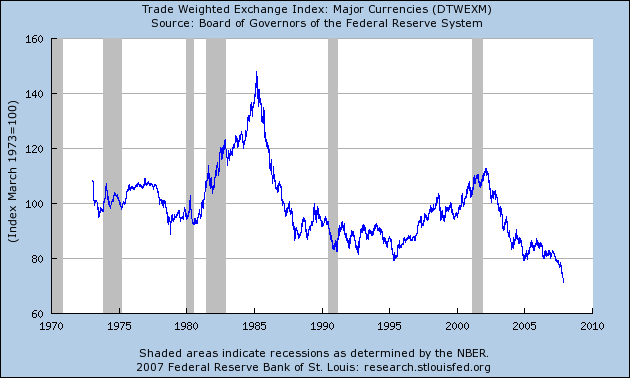

Figure 1: Narrow dollar index. Source: Federal Reserve via St. Louis Fed FRED II, accessed November 8, 2007.

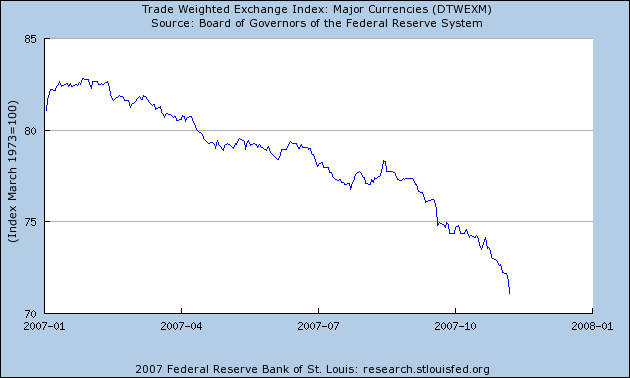

Figure 2: Detail, Narrow dollar index. Source: Federal Reserve via St. Louis Fed FRED II, accessed November 8, 2007.

First, I think it’s helpful to break motivations for exchange rate movements into (1) business-cycle macro-related factors, and (2) structural factors related to central bank/sovereign wealth fund holdings (as dramatically exemplified by Wednesday’s events), and investor preferences regarding currency of denomination. (Intermediate term factors like productivity trends I’ll lump in with (1) for now; see this post for a treatment.)

The factors in (2) have been discussed in this weblog upon numerous occasions. While I don’t want to minimize the importance of these factors, they are difficult to model, partly because we do not directly well observe reserve accumulation. Nor do we have models of reserve accumulation that have particularly high predictive power. In other words, exactly because “tipping points” and other similar nonlinearities are observed infrequently, these effects are difficult to incorporate into econometric models that rely upon being able to observe phenomena repeatedly (for an academic treatment over the long horizon, see this piece by myself and Jeffrey Frankel).

So, in this survey, I’ll focus on those factors that fall in the category (1). These include the standard monetary factors like money, incomes, interest rates and inflation rates.

Now, as I’ve observed before, one of the key stylized facts regarding the empirical modeling of exchange rates is the one associated with Meese and Rogoff’s 1983 paper: that it is difficult to outpredict a random walk in out of sample forecasts where the ex post values of the explanatory variables are used (what are sometimes called ex post historical simulations).

This stylized fact has been remarkably durable in its 20 year history. After some work which seemed to indicate that one could outpredict a random walk at long horizons (Mark (1995) [pdf] and Chinn and Meese (1995) [pdf]), subsequent research demonstrated that this long horizon outprediction was an artifact of sample period, at least insofar as RMSE criteria are concerned. Cheung, Chinn and Fujii (2003) [pdf] showed that at long horizons, one could find cases where the random walk was outpredicted at long horizons using interest rate parity, but not (typically) structural macro models of the type examined by Meese and Rogoff.

One path has been undertaken by Roman Frydman and Michael Goldberg, where they have dispensed with the rational expectations approach, and forwarded what they call the “imperfect knowledge expectations”. In a recent paper [pdf], they explain their approach thusly:

Why do academic economists believe that short-run currency fluctuations are not

connected to macroeconomic fundamentals, whereas the individuals most connected to

financial markets obviously do? Our answer is that market participants and observers

recognize that the relationship between the exchange rate and macroeconomic

fundamentals changes at times and in ways that cannot be fully foreseen. While they

may use economic theory to understand and forecast markets, they recognize that they

cannot base their actions solely on a fixed model.

…

The basic premise of our approach, called “imperfect knowledge economics” (IKE), is that the search for sharp predictions of market outcomes is futile. Market participants and policy makers must cope with ever-imperfect knowledge in forecasting the future exchange rate. As a result, our knowledge and our institutions (e.g., the conduct of monetary policy) change over time. Indeed, capitalist economies provide powerful incentives for individuals to find new ways of thinking about the future and the past. In such a world, it is rather odd for economists to expect that a fixed set of economic fundamentals would matter in exactly the same way for more than 30 years, or that they could fully prespecify how this relationship might have changed over time.

It is thus not surprising that academic economists have found that their models forecast exchange rates no better than flipping a coin does. This finding still attracts much attention among academic researchers. Indeed, it is one of the main reasons why they have concluded that markets participants’ irrationality, rather than macroeconomic fundamentals, moves currency markets.

…

What are the practical implications from this view of the world? They lay their views out in a newly published book. In this paper, they draw out the implications for the dollar over the near future.

In our model, the exchange rate is determined by the interplay between the decisions of bulls and bears, who base their forecasts in part on different interpretations of trends in macroeconomic fundamentals. A market participant may well decide that, because the dollar/euro exchange rate is, say, 40 percent overvalued relative to PPP, as it currently is, she wants to be a net seller of euros. However, in a world of imperfect knowledge, the gap between the actual and PPP exchange rates is merely one of many fundamental factors that market participants might reasonably rely on in forming their forecasts. Research shows that other fundamental variables that have been important at various times over the past 30 years include domestic and foreign interest rates, GDP growth rates, unemployment rates, current account imbalances, inflation rates, and monetary policy announcements. These variables may exhibit trends that cause market participants in the aggregate to revise their exchange rate forecasts further away from PPP, thereby causing the exchange rate to follow suit. This IKE view of exchange rate swings, therefore, rationalizes the accounts of the euro’s recent rise that point to the importance of macroeconomic fundamentals.…

Trends in macroeconomic fundamentals are not the only factors that drive currency fluctuations and swings in exchange rates. How and when individuals revise their forecasting strategies also matter. Such decisions can depend on many factors, including prior forecasting success, economic and political developments, emotions, or, as we will suggest shortly, the size of the departure of the exchange rate from PPP. The revision of forecasting strategies and its timing, therefore, is to some extent non-routine, so that modeling such decisions with fully predetermined rules, as contemporary models do, is bound to fail.

Given that some of my own research suggests nonlinearities in exchange rates [pdf], and changes in what factors traders consider important [pdf], I’m sympathetic to some of the ideas Frydman and Goldberg propound. At the same time, I should observe that a quite different approach to thinking about exchange rates adheres to the rational expectations view — and indeed takes the inability of typical exchange rate determinants to predict the exchange rate as proof that the rational expectations/present value approach is correct. This approach, developed by Engel and West [pdf], was discussed in this post. In a paper provocatively titled Exchange Rate Models Are Not as Bad as You Think [ppdf] Engel, Mark and West write:

Engel and West (2004, 2005) propose testing two implications of the present value models. They emphasize that because we acknowledge that there are “unobserved fundamentals” (e.g., money demand shocks, risk premiums), the exchange rate may not be exactly the expected present value of observed fundamentals. But if exchange rates react to news about future economic fundamentals, then perhaps exchange rates can help forecast the (observed) fundamentals. If the observed fundamentals are the primary drivers of exchange rates, then the exchange rates should incorporate some useful information about future fundamentals. We verify this proposition using Granger causality tests. Engel and West (2004) also develop a technique for measuring the contribution of the present discounted sum of current and expected future observed fundamentals to the variance of changes in the exchange rate, which is valid even when the econometrician does not have the full information set that agents use in making forecasts. Here we find that the observed fundamentals can account for a relatively large fraction of actual exchange-rate volatility, at least under some specifications of the models.

Standard tests of forward looking models under rational expectations make the assumption that the sample distribution of ex post realizations of economic variables provides a good approximation of the distribution used by agents in making forecasts. But (as Rossi (2005) has recently emphasized) when agents are trying to forecast levels of variables that are driven by persistent or permanent shocks, the econometrician might get a very poor measure of the agents’ probability distribution by using realized ex post values. The problem is enhanced when the data generating process is subject to long-lasting regime shifts (caused, for example, by changes in the monetary policy regime.) For an economic variable such as the exchange rate — which is primarily driven by expectations — it might be useful to find alternative ways of measuring the effect of expectation changes.

See this post on present values and exchange rates.

Although these paragraphs appear quite damaging to the enterprise of using fundamentals to prediction future exchange rate movements, I don’t believe that the situation is as dire as indicated by this passage. Indeed, in this same paper, they observe that there are instances when exchange rates can be forecasted.

While we argue that theoretically the models may have low power to produce forecasts of changes in the exchange rate that have a lower mean-squared-error than the random walk model, we also explore ways of increasing the forecasting power. Mark and Sul (2001) and Groen (2005) have used panel error-correction models to forecast exchange rates at long horizons (16 quarters, for example.) We find that with the increased efficiency from panel estimation, and with the focus on longer horizons, the macroeconomic models consistently provide forecasts of exchange rates that are superior to the “no change” forecast from the random walk model.

It may seem that some of these ideas are too abstract to be of any relevance to thinking about where exchange rates will go. Yet, as highlighted above, there does seem to be some evidence that at long horizons, exploiting cross-country information, one can find evidence of predictive power.

Perhaps more interesting is some recent work by Engel and West, as well as Molodtsova and Papell, suggesting that Taylor rule fundamentals (namely output and inflation gaps) can be used as predictors of exchange rates. I discussed this point in this post from January. From Molodtsova and Papell:

Although the role of interest rate differentials for exchange rate determination has been previously studied, the Taylor rule approach to interest rate modeling is a relatively unexplored area. It introduces a multivariate structure into exchange rate behavior, which generates a richer set of dynamics and has the potential for producing interest rate forecasts with higher predictive ability. Mark (2005) considers Taylor rule interest rate reaction functions for Germany and the U.S. and estimates the real dollar-mark exchange rate path assuming that the exchange rate is priced by uncovered interest rate parity. He provides evidence that the interest rate differential can be modeled as a Taylor rule differential and the real dollar-mark exchange rate is linked to the Taylor rule fundamentals, which may provide a resolution for the exchange rate disconnect puzzle. Engel and West (2006) construct a “model-based” real exchange rate as the present value of the difference between home and foreign output gaps and inflation rates, and find a positive correlation between the “model-based” rate and the actual dollar-mark real exchange rate.

We evaluate the out-of-sample performance of models with symmetric and asymmetric Taylor rule fundamentals using the Clark and West adjustment of the DMW statistic. In order to construct Taylor rule fundamentals, we need to define the output gap, and we use deviations from a linear trend, deviations from a quadratic trend, and the Hodrick-Prescott filter. In accord with recent work on estimating Taylor rules for the United States, we define potential GDP using “semi-real time” trends which are updated each period.

The results provide more evidence of short-run exchange rate predictability than we found by using monetary, PPP, and UIRP fundamentals and support the idea that the Taylor rule plays an important role in explaining exchange rate behavior. For the symmetric model, we find statistically significant evidence of exchange rate predictability at the 1-month horizon for 6 of the 12 currencies using at least one of the output gap measures. For the asymmetric model, we find similar evidence of exchange rate predictability for 7 of the 12 currencies. As with the earlier models, the predictive power of the models with Taylor rule fundamentals decreases sharply with the forecast horizon.

What I take from this discussion is that some of the movements in the dollar are explicable in terms of fundamentals. The fundamentals that matter differ depending upon the horizon, with perhaps Taylor rule fundamentals (and consequently revisions to expectations regarding those fundamentals) driving the exchange rate at short horizons. This conclusion manifests itself in the tremendous impact revisions in expected inflation and output gaps manifest themselves into exchange rate changes, many times in ways not consistent with say flexible-price or sticky-price monetary models, or for that matter, some productivity based models.

I also think conventional monetary model fundamentals matter at longer horizons. These include money stocks, incomes, interest rates and inflation rates, and possibly the relative price of nontradables (this is where productivity trends can come into play). This predictability might not be seen in the RMSE criteria typically used, but sometimes shows up in direction of change statistics.

But, traveling full-circle, I want to stress that these factors overlay the structural factors (in category 2) that are in some sense harder to model. Will central banks change the pace of dollar acquisition (say because they change their pegging currency, or allow greater exchange flexibility? Will they in fact actually try to decrease dollar holdings? What will sovereign wealth funds do? What are investors’ views regarding the substitutability of dollar denominated assets versus euro or pound denominated assets? Because some of these questions pertain to infrequent, discrete, events (de-pegging from the dollar), or to relatively new phenomena (SWFs), or to imperfectly measured relationships (investor perceptions of substitutability), one should expect much greater uncertainty surrounding the effects of these structural changes.

This assessment is consistent a view I forwarded (along with others) two years ago. In a Council on Foreign Relations report [pdf], I argued that one of the implications of happily borrowing away at the Federal and national levels (the budget deficit and the current account deficit) was that, given the source of the funding, we would place the fate of the dollar and other asset prices to some extent in the hands of foreign, state, actors. Current events have, I think, vindicated that view.

Technorati Tags: dollar,

euro,

Taylor rule,

interest rate parity, present+value,

imperfect knowledge economics,

reserve accumulation,

sovereign wealth funds

Menzie,

Very thoughtful piece, and very cautious, given the continuing strength of the Meese-Rogoff random walk result, out of which you carefully avoided saying a bottom line of whether the US dollar is going to go up or down in the near future, :-).

I also note that you did not cite Engel-Hamilton, another study that suggested long term movements of ER in the data, although Jim now diplomatically defers to you on this matter…

Barkley Rosser: Thanks for the compliment. As you observe, this survey is not comprehensive. My own view, informed by a reading of the papers cited, is that the dollar will continue to face downward pressure overall, on the cyclical side. The floor is placed by how policy rates in the euro area and UK move (if downward, while US holds steady, then downward pressure is removed; here is where the Taylor rule framework is most helpful). On the other hand, the structural factors are all downward (except for transitory flight-to-safety motivations which would come from geopolitical events).

Since I was referring to recent thinking, I didn’t cite Engel-Hamilton. In any case, as I’ve remarked in previous rejoinders, Engel (JIE, 1994) highlights that even if long swings are in the data, they are not obviously exploitable in out-of-sample forecasting. It may be that other types of regime-switching is more relevant, say vector threshold autoregression built on PPP. See this paper by Deokwoo Nam, a PhD student (on the job market) here at UW.

Speaking of the BoE and ECB, they stood pat today. I think there’s a political economy story in here as well, especially with regard to the ECB. The historical record would likely show that, in times of turmoil, the Fed has had very little compunction in cutting rates regardless of what happens to the dollar. What point is there in maintaining central bank independence when you get this result? It is pandering, quite simply.

OTOH, the ECB has been concerned with protecting the value of the Euro even if it causes some harm to EU exporters. It makes me wonder why, given the opportunity, more folks don’t switch out of the dollar faster even as it plumbs new depths on a daily basis. Fed “ride the Euro high and shoot the dollar down” cowboy-style central banking does holders of dollars no good.

Political economy bottom line: The Fed doesn’t care much if at all about preserving the dollar’s role as a store of value. The ECB, thank heavens, does. Given such a scenario, the logical course of action for anyone with an IQ north of Forrest Gump’s is clear. The tipping point draws closer…

I argued that one of the implications of happily borrowing away at the Federal and national levels (the budget deficit and the current account deficit) was that, given the source of the funding, we would place the fate of the dollar and other asset prices to some extent in the hands of foreign, state, actors. Current events have, I think, vindicated that view.

In Canada we were forced to face that fact in 1994, when global bond markets collapsed as the Fed hiked rates and weaker players – such as Canada at the time – were forced to the wall. I suspect that it was a very sobering experience for the Ministry of Finance mandarins to contemplate an actual possibility of a Canadian 10-year bond auction failing.

I was on the phone on one of those days with a salesman from one of the major bond desks – talking very tough about how it wasn’t their job to finance the Government all by themselves! They were bidding for exactly what they’d pre-sold, not a penny more!

It was around that time that (then Prime Minister) Chretien made one of the most sensible remarks ever uttered by a politician. The quote doesn’t appear to be on-line anywhere, but when explaining the need for massive cuts in federal spending he said (something like): We’re not going to get our house in order because the bond markets are telling us to! We are going to get our house in order so we don’t have to care what the bond markets think!

An attitude like that will eventually reach the White House. But not before there’s a lot more pain than there has been so far.

Speaking of the dollar’s cliff diving, I have a few questions for you, my economic betters.

1) Does ANY other reputable central bank engage in remotely comparable selection to the Fed’s measures of inflation ex-food, ex-energy, and de facto ex-housing? (Does it exclude healthcare and education as well?)

2) Can anyone tell me of any items usually excluded from the core CPI basket that have *deflated* over the past five years?

I can understand reasons for a moderate weakening of the dollar. I believe Bernanke sees the United States in a position analogous to Great Britain in 1927, with a high trade deficit and persistently overvalued currency. And instead of allowing the Chinese (=US in 1927) to perpetuate a system which will otherwise end violently, Bernanke is turning the screws on the Chinese (who are politically unable to revalue the yuan themselves) until domestic inflation scares them more than millions of lost exporter jobs.

But having said that, the Fed is going overboard. The dollar has lost enormous international credibility during Bernanke’s tenure. In terms of gold, euros, or any other major currency, US assets have been in recession for quite some time and inflation is WAY higher than what official figures state. No that isn’t quite a fair comparison, but it’s a very, very different universe from the one that Bernanke and Mishkin live in.

Just my two depreciating cents.

Gosh, it looks like Menzie has become anonymous!!!

🙂

After reading Menzies very interesting overview of exchange rate economics, and a kind mention of our book and recent article, Roman and I have several comments. Menzie points out that we urge economists to abandon REH as a way to model forecasting behavior. Since Menzie does not state the many reasons, both theoretical and empirical, that we elaborate on in our book http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8537.html, perhaps we can take this opportunity to summarize some of our key arguments.

We show formally in our book (chapter 3) that, in a world of imperfect knowledge, REH is not consistent with rational behavior, as is commonly believed. A simple way to see this is that in most models, REH implies a fixed forecasting strategy. But not only do market participants not rely on one fixed strategy, let alone the one implied by an economists model, but they do not do so for a good reason: it would imply passing up obvious profit opportunities endlessly. And as Bob Lucas himself has emphasized, this would be an indication of having the wrong theory. This is why we have argued that REH models are the wrong theory. (BTW, Bob Lucass argument that models embodying an inconsistency between their representations on the individual and aggregate levels are the wrong theory immediately applies to non-REH behavioral finance models. The reason being is that they formalize their behavioral insights in mechanical ways.)

Menzie suggests that macroeconomic fundamentals may matter, but only at longer horizons. In our article and book, we argue that economists need to give up searching for a fixed relationship between the exchange rate and macroeconomic fundamentals or for a relationship that changes in mechanical ways (see chapter 7). Incidentally, this also pertains to fully prespecified nonlinear models. We show in our book that macroeconomic fundamentals do matter, even in the short-run, but the way they matter changes; we find that different sets of fundamentals matter during different time periods (see chapter 15). Allowing for structural change is really the key.

Consider the following: U.S. current account deficits have been large throughout 1999-2007, while the value of the dollar rose steadily from 1999-2002 and fell steadily from 2002-2007. Many economists conclude from this experience that current account imbalances matter little for short-run exchange rate movements. But there is another possibility: market participants might have ignored current account imbalances in forming their exchange rate forecasts between 1999-2002, but have taken these imbalances into account when forecasting since 2002. Consequently, if we are to find evidence that macroeconomic fundamentals matter for exchange rates, we are going to have to allow for this kind of non-routine behavior and the structural change that results from it, the timing and form of which cannot be fully prespecified. Allow us to add that we will need to build economic theory that is consistent with such empirical findings and that allows us to distinguish between alternative explanations of market outcomes. This is what IKE attempts to do.

Barkley Rosser: Oops. Fixed it – I’m no longer anonymous.

With respect to the Canadian dollar, it seems that market traders have certainly changed how they view the relationship between the “loonie” and oil prices. For example, the standard Bank of Canada CDN/US model has energy prices entering the equation negatively – clearly that is not what traders have in mind these days as the CDN dollar’s ascent has closely tracked oil prices.

Menzie;

That’s a very interesting and ambitious summary, that I’m going to be rereading for a while. However, I’d like to offer some quick comments;

1) Monetary Models of the Exchange Rate: I think Amato and Swanson pretty convincingly destroyed the relevance of monetary models for output and prices by showing that unrevised money stock data have no stable relationship with prices or output. Isn’t it time to take data revision seriously in monetary exchange rate models (as Faust, Rogers and Wright do?)

2) Output Gaps and the Exchange Rate: If you thought revisions to monetary data were serious, you should look at output gaps! Orphanides has published extensively on this, as both Ken West and Charles Engel well know. How should we interpret results that claim that output gaps which can be constructed only years after the fact “determined” exchange rates?

3) On the CAD and oil prices, the Bank of Canada’s story changed a couple of years ago; work by Issa, Lafrance and Murray shows structural breaks in the original Amano-van Norden equation; specifically a change in sign in the oil price effect. (The paper is in the BoC WP series and is forthcoming in CJE.) The point is, even before the latest strength in the CAD, the Bank of Canada was arguing that oil prices tended to make their currency appreciate against the USD.

“On the other hand, the structural factors are all downward”

What about PPP? The dollar is now approaching the underdeveloped countries in terms of purchasing power, and is 25% undervalued compared with the euro. Shouldn’t this act as a break on the dollar’s descent?

Menzie: Love it when you do this.

Goldberg: Your book sounds interesting and I am sympathetic to your view but your discussion of the current account from 1999-2007 makes me very uncomfortable. Hopefully the following is not pedantic. In a multi-factor model, the current account can still forecast exchange rates over the long haul even if there are periods where it does not work in a single factor context. Other factors may just outweigh the current account in the short run. This does not mean that we need structural breaks but rather that we are missing some of the factors … we do not have the full model. That said, I do believe that forecasting factors lose power over time as the market prices them out.

van Norden: True real-time output gaps have historically forecast exchange rate movements. Their power has declined over time. More sophisticated metrics of economic performance have presumably taken their place.

checker: PPP is certainly one of the countervailing forces. There are some substantial puzzles with PPP. For instance, it is hard to develop consistent tradeable indices across countries. Weinberg et. al. have a paper on some of the issues.

Menzie: “True real-time output gaps have historically forecast exchange rate movements.”

Really? What did I overlook?

True may be a bit strong for the classification of the output gap to which I refer with deference to your work with Cayen, Jacobs etc. The public sector and academics do not have a monopoly on data and research … although they have a monopoly on publishing the results :-).

Looks to me as though the dollar has exhibited a steady trend rate of depreciation over 35 years of about 0.8% pa (which in my simple minded way I associate with the temptations of being a reserve currency) punctuated by a couple of +40% manias (1980-1985 and 1995-2002), both of which completely reversed in an orderly fashion over the following three years.

From this perspective there doesn’t seem to be anything odd, ‘low’ or threatening about the dollar’s level today.

Plus, if you want to understand investors’ preferences in relation to holding dollars, I think you should allocate most of your effort understanding their fears over time about holding other currencies/assets – that’s where most of the gyrations occur.

Simon: thanks for the tip – i’ll have to read the ssa, Lafrance and Murray paper.

Simon’s changed equation makes sense. Certainly one would expect an oil exporter like Canada to have an appreciating currency when oil prices rise relative to that of an oil importer like the US.

Regarding PPP, an older literature had a rough estimate of a tendency to mean revert towards PPP of about 15% per year. Obviously that is not a super powerful effect, which can easily be knocked off in the short run by all kinds of shocks and speculative movements and noise of all kinds of frequencies and sorts.

Thanks to all for a great discussion.

Emmanuel: I’m not sure I’d want to infer too much about general reaction functions given the brevity of the ECB experience and the change in regime for the Fed.

Simon van Norden: Thanks for the compliment. In addressing your first point, one can logically make the distinction between forecasting in real time (useful in the real world for making money), and out-of-sample historical simulations, which are used to assess the robustness of an empirical specification. I think that the relationship between revised fundamentals and the exchange rate is of interest for what it tells us about economic relationships. (I’ll note that the results of Faust, Rogers and Wright that you mention hinge most critically on the time span, rather than the revised/unrevised distinction.)

On point 2, regarding the real time data on output gaps, I would definitely defer to you. However, I’ll note that David Papell has brought my attention to one of his papers, comparing the usefulness of revised and real-time output gaps for exchange rate determination.

On point 3, your characterization fits my view. Oil and CAD strength are (now) positively associated.

jfund: Point of clarification — what’s a “true” output gap?

general comment: In all of this, I think we probably have to be careful about our use of the phrase “output gap”. Oftentimes, in these econometric models we use “filtered” data (HP, Band Pass, linearly detrended) rather than an economic-based output gap (based on demographics, capital stock, etc.), mostly on pragmatic grounds. This is obvious to practitioners in the field, but not to all the readers.

checker and Barkley Rosser: Yes, PPP matters, but it seems to be a “weak atractor”. That is, deviations from PPP can be very large before reversion sets in. This is the basis for the threshold autoregression models such as those estimated by Mark P. Taylor and Lucio Sarno. In the investment bank literature, this characterization shows up as plus/minus 20% bands around PPP for the thresholds.

I think (but am not certain) that the rate of reversion to PPP is typically faster than 15% per year when outside the identified thresholds, and zero (random walk) when inside.

As you, Simon and an established literature have pointed out, true is a bit loaded. In this context, it would mean vintage data (best available at time based on historical publications) and one-sided BP/HP or equivalent filter. For the most part, forecasting results appear to improve with the use of real-time rather than final data. For instance t-stats increase rather than decrease. This seems to be at odds with much of the intuition in the academic literature. Then again, I am forecasting returns not the endpoint of revisions of economic statistics.

This discusion is a good example of why people disrespect economists. The EMH guys dream up an intuitively sensible but highly reductionist and incomplete model of the exchange rate. They then find that it does not beat a random walk and infer from this that the markets are efficient and that those those who disagree are just idiot “noise” traders.

I believe the point of the paper was simply to point out that there is a difference between the failure of simple models to work and the notion that exchange rate trends are invisible to all. This is not equivalent to the author claiming that he can HIMSELF forecast an exchange rate, Barkley.

The BoC model on the CD$ is a good example of a sensible but perhaps too reductionist approach. If I understand the description offered above correctly, and I may not, the coefficient applied to the price of oil is independent of the level of the price of oil. In other words it is linear. But traders understand what such a model could not, that Canada is a high-cost oil producer and the the marginal influence of oil price changes should be a function of the level of the oil price.

That traders get what the model may not is evidence that the traders are smarter than the model, not that they are stupid.

“the value of the dollar rose steadily from 1999-2002 and fell steadily from 2002-2007”

The dollar rose in late 2004 and 2005 before resuming its fall.

Warren Buffett threw in the towel on his bearish dollar bet during this time, at least temporarily.

..as a longtime dollar bear, I have to agree: the fall has not been steady, at least not to those with short positions.

Consider the following: U.S. current account deficits have been large throughout 1999-2007, while the value of the dollar rose steadily from 1999-2002 and fell steadily from 2002-2007. Many economists conclude from this experience that current account imbalances matter little for short-run exchange rate movements. But there is another possibility: market participants might have ignored current account imbalances in forming their exchange rate forecasts between 1999-2002, but have taken these imbalances into account when forecasting since 2002.

I wonder if the tax cuts and war drums increased expectations by the economic players of higher Federal government deficits. Also I wonder to what extent market psychology plays a role. It seems the dollar’s fall has become a panic, with investors of varying sophistication all running for the exits as the US becomes less popular abroad and a persistent negative mood here. I wonder if the negative view of the US flows into (or out of) the falling dollar?

“In such a world, it is rather odd for economists to expect that a fixed set of economic fundamentals would matter in exactly the same way for more than 30 years, or that they could fully prespecify how this relationship might have changed over time.”

Perhaps, but the fundamental human motivations underlying proper economic analysis, as propounded by von Mises, do not change.

I’m not an academic economist, but I have a simpler suggestion: how about asking a currency trader what they do.

I think I can predict the jist of the answer.

In the short-medium run, everything revolves around the carry trade—whether to believe it (most of the time) and when to bail—and hence the real job is predicting the time derivatives of attitudes of central banks.

To the degree that fundamentals affect central bank decisions, they will affect currencies. But central banks look at some macroeconomic variables for some periods with concern, and later, for objective or subjective reasons, they don’t. It would be illogical for currency traders to do otherwise.

Matthew Kennel: Excellent idea. See this paper (dealing with US traders) cited in the post, as well as this (on UK traders).

Professor Menzie Chinn,

Posted by Matt Hartogh

As an economics graduate, as opposed to a student in business school, I learned the standard canonical explanation of exchange rate determination thanks to the Krugman and Obstfeld text.

In the short term, the primary determinant is interest rate parity IRP; in the long term it is Purchasing Power Parity PPP.

These work well as both a theoretical framework and a common sense analysis.

Currency traders, however, need not solve the rigorous mathematical problem to be successful in their trade. In fact, they dont have time to do it. They are up all night following the FOREX markets from Tokyo to New York to London. And it is their trading decisions, necessarily made in seconds, that have the greatest effect on the price of the dollar, the yen, and the euro. So you are quite right to factor in emotion and psychology in the movements of these currencies. The dollar”s fluctuations of late have more to do with their decisions than with fundamentals. I thought the euro would take a bigger hit over the troubles at EADS Airbus than it actually did, but apparently short term trading decisions predominated over long term forecasting. Recent moves by the fed on interest and the subprime lending crisis have motivated traders to sell dollars and buy euros. Still, in finance our paramount concern is ROI or Yield to Maturity, although in the currency markets, “maturity” may be only a matter of seconds.

The long term factors, however, look better for the dollar. If the dollar has sunk more this morning, the Eurozone may have a higher real GDP than the United States. Still, the US has a higher aggregate GDP in PPP than the Eurozone, and other fundamentals of the US economy are strong. For one thing, eurozone inflation in food products is high. According to PPP analysis, this would put downward pressure on the euro over the medium term. More important is the issue of labor market flexibility. The US has already gone through a lot of the pain of labor market rationalization, this adds efficiency to American business activities and its effect on productivity and GDP growth, and thus gives the dollar buoyancy in the medium and long term. In Europe, by contrast, labor market reform is being strenuously resisted and this should give euro supporters some cause for concern.

Matthew Hartogh

There is a kind of new truism emerging among financial market traders in general, which probably applies to forex traders as well. It posits three time horizons:

1) very short (basically within a day). This is driven by technical factors and econophysics-derived strategies based on very high frequency patterns.

2) intermediate (from a day to a year or some more, basically months). This is dominated by behavioral finance kinds of factors.

3) long run. (longer than a year). Market fundamentals, mostly PPP, with some effect from real interest rate differentials.