Matthew Higgins and Thomas Klitgaard at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York discuss the outlook for financing the deficit, going forward, in a new Current Issues. From the introduction:

To finance its large current account deficit, the

United States must attract the equivalent

amount of surplus foreign savings. In recent

years, the U.S. deficit has been large enough to absorb the

lion’s share of surpluses generated abroad. Indeed, from

1999 through 2006, the cumulative U.S. borrowing of $4.4

trillion amounted to some 85 percent of the net external

financing provided by countries with surplus saving.

Despite this heavy borrowing, however, the United

States has been the destination for little more than 30 percent

of total gross cross-border investments by other countries,

a figure that only slightly exceeds the U.S. share of

global GDP and is below the U.S. weight in global financial

portfolios. As a result, the United States has been able to

finance its large current account deficits without laying

claim to a disproportionate share of global foreign investment

or causing foreign external portfolios to become

dominated by U.S. assets.

This edition of Current Issues sheds light on these seemingly

incompatible developments by examining the

financing of the U.S. current account deficit from a global

perspective. We find that the recent period of large U.S.

current account deficits has also been one of rapid financial

globalization, with surplus and deficit countries alike

investing a record fraction of their saving abroad. This

sharp increase in cross-border investments has made it

possible for the United States to emerge as the world’s

principal net borrower while receiving an unremarkable

share of other countries’ gross external investments.

Facilitating this development is the fact that the rise in U.S.

cross-border investment has lagged the rise in global

investment by other countries.

These findings have important implications for the sustainability

of the U.S. current account deficit. In our view,

it might be harder to finance continued large current

account deficits on favorable terms if the recent wave of

financial globalization were to subside: The United States

would then have to attract a larger share of other countries’

foreign investments. It might also be harder to finance the

deficit on favorable terms were U.S. investors to participate

more fully in financial globalization by investing a larger

fraction of domestic saving abroad.

The key difference between some other approaches to viewing sustainability, and theirs (which is well grounded in the finance literature), is in their focus on the shares of total world assets.

Alternative Metrics

Our analysis of foreign portfolio exposure to the United

States is based on investment in the country as a fraction of

global cross-border investments. In our view, this approach

illustrates underlying trends while controlling for the ongoing

progress of financial globalization. Still, a look at how

exposure to the United States has evolved relative to global

saving and global wealth might shed additional light on the

sustainability of the U.S. current account deficit.

Since 2002, investment in the United States has absorbed

16.5 percent of the rest of the world’s saving, up from 14.3

percent during 1997-2001 and up substantially from 7.0 percent

during 1992-96. Is the recent figure high or low? If such

investment were sustained, assuming stable exchange rates

and similar asset price behavior in the United States and

abroad, claims on U.S. assets would trend toward 16.5 percent

of total foreign wealth. We cannot know the potential

limits on desired foreign exposure to the United States; the

limits depend, in part, on how far the recent wave of financial

globalization can progress. That said, a 16.5 percent figure

would not be out of line with the U.S. weight in the global

economy and the global financial markets.

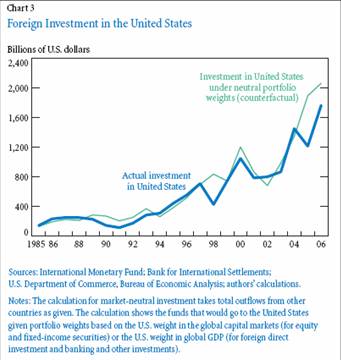

To highlight this point, consider the actual amount of investment in the U.S., compared to that predicted using their calculations.

Source: Higgins and Klitgaard (2008).

In other words, by looking at shares of assets, it doesn’t look like the stock of foreign investment in the US is out of line (keeping in mind substantive measurement issues, raised by the authors).

I particularly appreciated the nuanced view in which the authors conclude.

… Our results suggest that such globalization has

allowed the United States to finance large current account

deficits without experiencing sharper downward pressures

on the dollar and U.S. asset prices. However, a retreat from the recent pace of financial globalization by foreign investors

or an increase in the rate at which U.S. investors buy foreign

assets could make it more difficult for the country to sustain

a large current account deficit on favorable terms.

I think that this is a particularly salient point. The net inflows to the US over the past decade can be viewed in part as a stock-flow adjustment process. But the target “stock” might change as the attractiveness of US assets declines (think sub-prime and soon Alt-A’s, CDOs, and soon CDSs, etc.). At that point, the stock-flow perspective could look a lot like a “disorderly adjustment” in the flow perspective.

Technorati Tags: current account,

financial globalization,

net international investment position.

Professor Chinn, once again, thanks for highlighting and elucidating interesting research.