I was astonished when I heard that the Fed is contemplating

increasing the Term Auction Facility to $900 billion. I wanted to take another look at the ever-changing balance sheet of the Fed to see how logistically Bernanke might be able to perform such a feat.

The one power that the Fed unquestionably possesses is the ability to create money. It traditionally did so by buying Treasury securities from the public, crediting the sellers’ banks with newly created Federal Reserve deposits (a “liability” from the Fed’s point of view), and adding the securities purchased to the Fed’s asset holdings. Those newly created Federal Reserve deposits are essentially electronic credits that the banks could use to receive delivery of green cash from the Federal Reserve.

The first column of the table below provides a condensed version of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in the halcyon moments before the credit turmoil began in August 2007. By far the most important asset held by the Fed at that time was some $800 billion in Treasury securities, largely balanced on the liabilities side by a similar value for currency in circulation. Repurchase agreements at that time were used by the Fed as a vehicle to add reserves temporarily, while reverse repos entered on the liabilities side as a factor temporarily draining reserves. The residual reserve balances, after adding up all the factors supplying reserves and subtracting all the other factors absorbing reserves, were themselves a tiny number, under $7 billion.

| Aug 8, 2007 | Sep 3, 2008 | Oct 1, 2008 | |

| Securities | 790,820 | 479,726 | 491,121 |

| Repos | 18,750 | 109,000 | 83,000 |

| Loans | 255 | 198,376 | 587,969 |

|     Discount window |     255 |     19,089 |     49,566 |

|     TAF |     150,000 |     149,000 | |

|     PDCF |     146,565 | ||

|     AMLF |     152,108 | ||

|     Other credit |     61,283 | ||

|     Maiden Lane |     29,287 |     29,447 | |

| Other F.R. assets | 41,957 | 100,524 | 320,499 |

| Miscellaneous | 51,210 | 51,681 | 50,539 |

| Factors supplying reserve funds | 902,992 | 939,307 | 1,533,128 |

|   | |||

| Currency in circulation | 814,626 | 836,836 | 841,003 |

| Reverse repos | 30,131 | 41,756 | 93,063 |

| Treasury supplement | 388,850 | ||

| Other | 51,440 | 56,884 | 38,717 |

| Reserve balances | 6,794 | 3,831 | 171,495 |

| Factors absorbing reserve funds | 902,992 | 939,307 | 1,533,128 |

The Fed’s actions since August of 2007 have often been described as providing “liquidity”, though they were not doing so in the traditional sense of expanding reserves or the money supply. We see in the second column of the table above that the increase in currency in circulation between August 2007 and September 2008 was in fact quite modest, and reserve balances actually fell over that period.

The Fed did provide enough money creation to bring the fed funds rate, the interest rate at which banks lend those reserves to one another overnight, down from 5.25% in the summer of 2007 to 2.0% today. But a number of other interest rates, such as the rate banks lend to one another for a 3-month period, stayed well above that 2% overnight rate, signaling substantial frictions in the interbank market. To try to address those frictions, the Fed had been significantly changing the composition of the asset side of its balance sheet through the beginning of September 2008, while keeping the total assets essentially constant. These compositional changes included selling off $90 billion in Treasuries and replacing them with repos. This swap was implemented not because the Fed wanted the operations to be short-term, but because it was one device to make a market for the less liquid securities that the Fed accepted as collateral against the repo loans and a device for providing term loans to banks directly. Borrowing from the Fed discount window increased another $20 billion. The Fed introduced the Term Auction Facility in order to lend an additional $150 billion short-term, serving the same dual objectives of the repos. Maiden Lane LLC was created as a device for handling the $30 billion loan that was part of the Bear Stearns deal. All of these operations by themselves would have increased the money supply and the Fed’s total assets. To prevent that from happening, the Fed sold off a comparable volume of its holdings of Treasury securities. By the beginning of September 2008, the Fed had replaced more than $300 billion of its holdings of Treasury securities with assorted riskier loans.

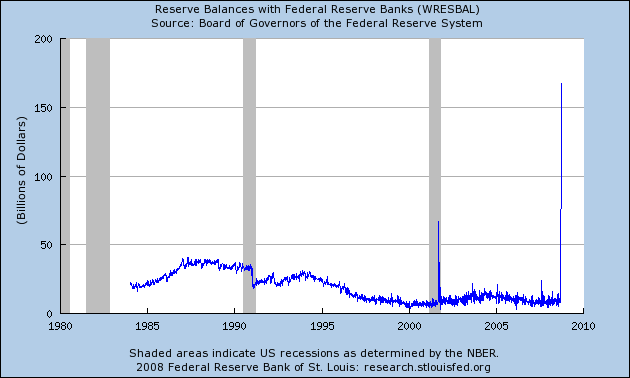

But the real action began last month. As reported in the third column of the table above, the Fed expanded its total asset holdings by $600 billion over the last 30 days, with less than a third of this going directly into reserve balances. The graph below puts the latter magnitude in perspective. When the World Trade Center towers burned down on September 11, 2001 many of the financial institutions that played a key role in trades of government securities and interbank loans were wiped out or incapacitated, posing potentially huge liquidity problems. Reserves ballooned to $67 billion, as excess reserves simply piled up in some banks while others remained in need. Last week’s spike of $171 billion was 2-1/2 times as big– the breakdown of interbank lending last week proved more profound than that caused by the physical disruptions in New York in 2001.

|

Anyone who suggests that last week’s ballooning reserve deposits represent inflationary pressure or the Fed monetizing the deficit simply doesn’t know what they’re talking about. Banks are sitting on the reserves, not withdrawing them as cash. When markets settle down, the Fed can and will absorb those reserves back in with sterilizing sales of Treasury securities, just as it did in 2001 or after the more modest spike in August 2007. Providing new reserves aggressively is absolutely and unquestionably the way the Fed needs to respond to this kind of development.

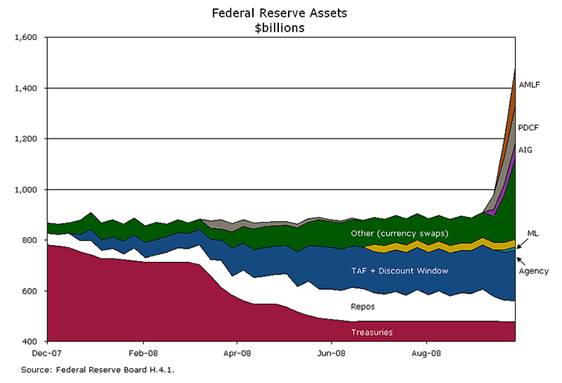

But referring back to the original table, we see that creating new reserves, as dramatic as it was, was dwarfed in magnitude by some of the other actions the Fed took over the last month. The Fed is now lending out an additional $150 billion in its primary dealer credit facility, providing overnight loans to primary security dealers who could not borrow directly from the Fed’s discount window. Again this lending seems very much in the spirit of addressing the immediate liquidity needs, defined narrowly in terms of stressed overnight lending markets. Then there’s another $150 B for the AMLF– the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility, or the Name Too Long Even to Acronymize, $61 B for “other credit extensions” (primarily the AIG deal) and close to a new $300 billion over the last year in “other Federal Reserve assets”, in which currency swaps are probably the biggest single item. A hundred billion here, and a hundred billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money. Macroblog has a nice visual of how these goodies all add up:

|

But how did the Fed acquire all that stuff, with “only” a $160 B increase in reserve balances and a $30 B increase in currency outstanding? The answer is to be found in a new entry on the liability side described as “Treasury supplementary financing account.” This was announced by the U.S. Treasury through the following somewhat obscure release:

The Federal Reserve has announced a series of lending and liquidity initiatives during the past several quarters intended to address heightened liquidity pressures in the financial market, including enhancing its liquidity facilities this week. To manage the balance sheet impact of these efforts, the Federal Reserve has taken a number of actions, including redeeming and selling securities from the System Open Market Account portfolio.

The Treasury Department announced today the initiation of a temporary Supplementary Financing Program at the request of the Federal Reserve. The program will consist of a series of Treasury bills, apart from Treasury’s current borrowing program, which will provide cash for use in the Federal Reserve initiatives.

Announcements of and participation in auctions conducted under the Supplementary Financing Program will be governed by existing Treasury auction rules. Treasury will provide as much advance notification as possible regarding the timing, size, and maturity of any bills auctioned for Supplementary Financing Program purposes.

Here’s what I take that to mean. I gather that the Treasury auctioned off some extra T-bills to the public, in addition to their usual weekly

auction, and simply kept the receipts as deposits in an account with the Fed. If that were the end of the story and the Fed kept its total liabilities constant, it would result in a huge (completely infeasible technically) drain on reserve balances and currency in circulation, as banks sought to deliver reserves to the Treasury’s account to honor their customers’ purchases of the T-bills. So the Fed offset the supplemental Treasury auction with a matching purchase of private assets, such as the PDCF and AMLF, thereby temporarily delivering reserves to banks which the banks in turn could hand over to the Treasury supplementary account. The net result of such dual Treasury/Fed operations is that the newly created “reserves” would just sit there in the Treasury supplementary account doing nothing other than standing as an accounting entry. In other words, the device allowed for a huge expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet without causing any change in currency in circulation or reserve deposits.

Which leaves Bernanke’s gun cocked and reloaded, and he’s ready to keep shooting. And so the Fed announced on Monday that it’s up, up and away for the term auction facility:

The sizes of both 28-day and 84-day Term Auction Facility (TAF) auctions will be boosted to $150 billion each, effective with the 84-day auction to be conducted Monday. These increases will eventually bring the amounts outstanding under the regular TAF program to $600 billion. In addition, the sizes of the two forward TAF auctions to be conducted in November to extend credit over year end have been increased to $150 billion each, so that $900 billion of TAF credit will potentially be outstanding over year end.

But those Monday developments are ancient history now, because on Tuesday we got a

brand new acronym:

The Federal Reserve Board on Tuesday announced the creation of the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), a facility that will complement the Federal Reserve’s existing credit facilities to help provide liquidity to term funding markets. The CPFF will provide a liquidity backstop to U.S. issuers of commercial paper through a special purpose vehicle (SPV) that will purchase three-month unsecured and asset-backed commercial paper directly from eligible issuers. The Federal Reserve will provide financing to the SPV under the CPFF and will be secured by all of the assets of the SPV and, in the case of commercial paper that is not asset-backed commercial paper, by the retention of up-front fees paid by the issuers or by other forms of security acceptable to the Federal Reserve in consultation with market participants. The Treasury believes this facility is necessary to prevent substantial disruptions to the financial markets and the economy and will make a special deposit at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in support of this facility.

I’ve had 4 calls today from reporters, all asking the same question:

Will it work?

I wish I knew the answer. I bet Bernanke wishes he knew, too.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

term auction facility,

TSLF,

TAF,

term securities lending facility,

credit crunch,

Commercial Paper Funding Facility

Wow. Ben and Hank are doing all they can to keep the dike from bursting. Let’s hope the water goes down before their thumbs wear out.

This seems like magic.

What’s the downside of this? What keeps the Fed from ‘reloading’ again and again, if anything?

very nice. and if the Fed starts buying on top of all that some of the T bonds issued to finance the 700 billions Paulson plan ? isn’t it a monetization of debt ?

Anywas the quality deterioration of the Fed assets is normally a negative for the value of the currency

regards

Miju

The leverage of the Fed was about 1,15 (790-902) at the beginning, now it is more than 3 (450-1500).

Sorry… it’s 490 vs 1530, but le ratio is ok

Looks like the balance sheet should be labelled as millions USD?

That was a great post. thank you

With the focus on the Treasury plan, it was easy to lose sight of the creativity and aggressiveness the Fed-Treasury partnership is showing. The recent series of credit provisions are it seems to me much more important than today’s rate cut.

Thanks much, Geoff, corrected now.

I’m still trying to figure out what these swaps are doing. $320 of “other assets” is mostly currency swaps (soon to expand to $620 it was announced last week). We could think of that as the offsetting asset for (most of) the $389 borrowed from the Treasury, in which case…

Treasury sells extra T-bills, deposits the dollars with the Fed, which swaps them to other central banks for euros etc. Those CBs then loan out the dollars for … what collateral? If they’re only lending against T-bills then we’ve completed a circle with little net effect. If they’re lending via repos or their own TAF-style facilities, then this looks like a way for other CBs to add their balance sheets to the Fed’s in a joint effort to (hopefully temporarily) take some of these illiquid assets out of the market, replacing them with T-bills.

Does that make sense? Or can someone explain what the currency swaps are accomplishing?

JDH wrote:

Anyone who suggests that last week’s ballooning reserve deposits represent inflationary pressure or the Fed monetizing the deficit simply doesn’t know what they’re talking about. Banks are sitting on the reserves, not withdrawing them as cash. When markets settle down, the Fed can and will absorb those reserves back in with sterilizing sales of Treasury securities, just as it did in 2001 or after the more modest spike in August 2007. Providing new reserves aggressively is absolutely and unquestionably the way the Fed needs to respond to this kind of development.

Professor,

Let me first say that this is a terrific analysis. You have addressed things that I have been discussing with friends but have not seen discussed anywhere else (especially the Treasury auction of t-bills).

Now let me offer a slightly dissenting opinion concerning your comments I have quoted above. First, the FED does not facilitate inflation only by increasing the money supply. We cannot forget demand. When the demand for money increases or decreases if the FED does nothing there will also be inflation or deflation with a floating currency. So just because the FED balance sheet does not change does not mean that we do not have inflation or deflation. Under a real gold standard this adjustment mechanism is virtually automatic as money substitutes increase or decrease based on gold flows.

Another consideration is the Cantillon effect where money entering the economy does not enter equally through the entire economy. The Cantillon effect had a significant influence on channeling money to support reduced lending criteria for loans that created the credit crisis. The tendency was to obscure additional money from increasing overall inflation in the system. Most of the impact of the extra money was pushed into the housing bubble.

Under current conditions I do not disagree with your suggestion of increasing FED reserves provided the Fed actually does as you suggest and withdraws excess reserves when indicators show excess reserves. My only concern is that the FED indicators are 12-18 months behind economic changes. Were they using the price of gold as their indicator they would manage the value of the currency much better, as did Greenspan in the early 1990s. But in the latter part of the 1990s when Greenspan moved away from gold to the Greenspan indicator he missed the deflation until it was well underway.

Seems to me that the Fed should hire Bob Engle. He was always good with acronyms.

I knew it was only a matter of time before the ‘monetizing debt’ poster would appear. And lo and behold it took all of three posts.

When you are stating that “people don’t know what they are talking about” and you have commenters stating that “it is like magic” then clearly your communications are failing.

Rather than implying there is nothing to worry about as a nation (ie, worriers “don’t know what they are talking about”) and there are no macroeconomic consequences of the Fed’s actions (after all, it is “magic”) why not enlighten everyone and very specifically and very clearly lay out the short and long term *downside* of the Fed’s actions.

You may believe the Fed had to act – now be honest and lay out the possible consequences macroeconomically of those actions.

DickF and cas127, let me clarify. I am not in this post taking on the broader question of whether Fed actions overall will prove to be inflationary, though my current opinion, for what it’s worth, is that they will not, an issue which I should perhaps address in more detail at some future point.

Instead, the passage to which you both responded was intended to apply quite narrowly to the interpretation and implications of the huge surge in Federal Reserve deposits between September 3, 2008 and October 1, 2008.

James,

Please explain for us mortals. I admit to being too dumb to understand the magic.

To me, being in business, is this not akin to a company issuing shares from treasury? Ultimately, if you do this too much then you end up with dilution. Therefore regularly you are forced to make share buybacks to counter the dilution. The money for share buybacks have to come from either earnings or else it requires more leveraging of the balance sheet (increased debt to buy shares).

If the share buybacks are rasied through debt then at some point a company will become debt ridden and face downgrades from rating agencies and will have to pay higher interest rates in order to secure credit.

Am I understanding things correctly? (In essence I am equating dilution with inflation – there is no inflation if shares are bought back using a more leveraged balance sheet – but this does not mean there arn’t consequences?)

If so what does the increased debt burden mean – could it ultimately weaken the dollar as creditors are harder to attract?

Obvioulsy in the current “panic” – the short term – there is a flight to safety – so in the short term everyone is flocking to USD T Bills. This actually helps the FEDS right now….but what about the longer term after the dust settles?

Please explain?

Confused and Corentin draw an interesting analogy to leverage. I discussed earlier who is assuming the risk that the new loans the Fed has provided do not perform. My answer is that the ultimate risk is borne by the Treasury, and will take the form of the Fed not returning as much of its interest income to the Treasury if the loans are bad. But do not forget that Treasury receipts will also plunge if the Fed fails to prevent a financial meltdown.

Professor,

Am I misunderstanding or is your attribution of the role of repos and non-repos the wrong way round? In a repo the Federal Reserve sells Treasuries with an agreement to repurchase them, thus DRAINING reserves (on a temporary basis) from the system.

Or am I missing something?

Eoghan, a Fed repo is basically a collateralized loan from the Fed to the counterparty, and therefore adds reserves for the duration of the repo. See this description from the New York Fed.

Wasn’t this the operating procedure used extensively by Treasury-Reserve authorities during WWII (Treasury supplementary financing account). And back then, legal reserves stood (as of Oct 21, 1943) at 83.1%, of deposit liabilities. The Treasury’s balances piled up in anticipation of the need for further funding, in the financing of the war. This ultimately became the rational, for the long-standing exclusion of the Treasury’s General Fund Account, from the assets included in the money stock.

now the world have coordination devices despite financial international contagion. today we have emerging countries internal market growth.the system will be in a new steady state without crash. all is different from old episodes of financial crisis. in the end will have more financial concentration and more regulation.today we have big gap real economy and the financial system.tomorrow the gap will be small than today.we in brazil made the home lesson in the 90s and now we have a regulated and storng bank systems. we can not work withe the economics models of general equilibrium and laplacian probabilities. whne the black swam appear we all are in trouble thanks best regards

A cynical mind might suspect that the difference between the upper line and the red area marked “Treasuries” is the amount of bad paper with which the so-called free market conservatives are going to stick the taxpayers, thereby socializing the costs of their corruption and incompetence.

I gather that the Treasury auctioned off some extra T-bills to the public, in addition to their usual weekly auction, and simply kept the receipts as deposits in an account with the Fed. … In other words, the device allowed for a huge expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet without causing any change in currency in circulation or reserve deposits.

Umm, there’s one huge problem with this logic: crowding out. By raising the return on T bills, Treasury reduces the cost of fleeing in panic from the commercial paper market — and makes it harder for the private sector to borrow.

Think about it: as long as people fear 1 – 2% losses on commercial paper backed accounts, the money market funds can not be in equilibrium until the returns on T bills are negative (which obviously would make the jobs of fund managers rather difficult).

Of course, money market fund insurance changes the balance a bit, but most likely the fact that T bill rates have risen above 0.5% even as commercial paper markets are frozen is a sign that policy intervention is pushing the market away from equilibrium, not towards it. I think Treasury should be supplementing the Fed via notes and bonds, not bills.

I agree and disagree with James Hamilton regarding the inflation-risk associated with these extraordinary developments in the Fed’s balance sheet.

Certainly the effect of the Treasury’s supplemental financing offsets the purchase of bad private sector debt by the Fed as far as money supplied to the banking system goes, and that these moves are hence neutral with respect to inflation. But this represents only the short-term picture. Longer-term, these additional Treasury bonds are out there, and they are on top of a huge amount of national debt still outstanding. First, the reality is that there is no way this debt can be paid off out of taxation. Second, the Fed will not want the deterioration in the quality of its assets to be permanent. Therefore it is in both the Treasury’s interest and the Fed’s interest for the latter eventually to purchase outright a good deal of the increased quantity of Treasury bonds in the coming years.

Furthermore, a great deal of the increase in the Fed’s assets represents loans to the private financial markets. But given the state of such markets, how soon can these additional loans be expected to fully unwind? The not unreasonable assumption is that these loans will be rolled over, and that some of the money lent will be used to finance the purchase of Treasuries and certain categories of commodities. Meanwhile, the real economy will go into a deep recession, and the banks will be reluctant to finance long-term business investment.

So I predict a continuation of the liquidity trap, and moderately severe stagflation. Quite a combo!

But in any case, it’s hard to see how the Fed can get from where its balance sheet is now back to anywhere near where it was in August 2007, sans some degree of monetization of both private (commercial paper, MBS, and writing off some loans) and (the ever-burgeoning) public debt.

Why not do this on a scale much larger? Balloon the balance sheet to $10 trillion. Or more! If a little bit is good, and you claim no downside risk, then a lot should be even better. Also, why even bother with the TARP silliness if they could have just done this in the first place. Call me VERY skeptical that (a) there is little risk, (b) this won’t eventually be inflationary.

Including the Kitchen Sink

One thing often overlooked by casual market observers is the enormous set of policy options available

The grave difference between today and the stagflation years of Nixon-Carter is simple: war!

We crawled out of the Vietnam disaster by 1974. Immediately, the government began to shrink the military spending, etc. Today, we are banging about the planet, losing trillions of dollars in epic wars against barely armed civilian militias and individuals! Peasants using cheap weapons are hammering us as we misspend huge sums, bombing mountainsides and shepherd’s tents. Just like we wasted many millions, bombing rice paddies and jungles during Vietnam.

So long as we persist in wild military misspending, we will have inflation as well as an unbalanced budget. This year, Congress voted to raise the amount we spend on our crazy military by over 6%.

Because our economic industrial base is mostly military [we deindustrialized all other sectors to an astonishing degree] this translates into INFLATION at home. And we export this inflation for we have bases all over the planet.

This is the reason our empire is going bankrupt, by the way. This is the definition of ‘unsustainable’. The Treasury and the Federal Reserve which bankrolls this deficit war spending, scramble to find ways of doing this without letting war spending inflation swamp our entire economy. So long as Congress keeps increasing war spending, it will swamp our economy.

The banks are hoarding cash. That is the problem. The liability and spread of a specific CD is completely unknown. The first CD auction for FMae and FMac was held on 6 October. Deficits at this auction will have to be paid up by the 15th October. Due to the complexity of the CDS derivatives, the bankers do not know who is going to have to pay these deficits, and whether their banking partners are going to remain solvent. The next CDS auction is tomorrow, Lehman Bros. That could lead to huge liabilities that will have to be paid up about 10 days later. Then this is followed by AIG. No date is yet announced. As a result of all this uncertainty, all the banks are hoarding capital, and others, like Bank of America, are moving up earnings statements and are making emergency rights issues.

If the Fed can stop the credit defaults right now; then the problem will be contained. If not, the CDS derivatives will send the entire global financial system into melt down. This is a 60 trillion dollar problem.

That is why governments are throwing everything they’ve got right now at the problem. The next 30 days will be crucial.

You don’t mention the TSLF. (http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/tslf_faq.html)

The Fed has been loaning Treasury paper in exchange for various assets as collateral. Starting several weeks ago, in order to loosen up the credit markets, they started accepting as collateral all investment-grade securities, equities and municipal and corporate debt rated triple-B or higher. Previously, only Treasury securities, agency securities, and triple-A rated mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities could be pledged.

I think these are shown as Other Loans on the Fed balance sheet, and they have ballooned to over $400 billion in the past few weeks. Can anyone explain why this low quality collateral is not a risk?

While it might be true that the FED’s balance sheet operations do not have any inflationary consequences, it is equally true that too many Foreign Central Banks have monetized copious amounts of treasuries over the past many years.

This disfunctional monetary arrangement has made demand for official currencies much weaker. The Dollar especially relies heavily on FCBs to keep its value.

Unless I’m not understanding, it seems there is a very simple way to summarize this…

The Supplementary Financing Program allows the Fed to conduct sterilization on an unlimited scale (to offset its growing operations) by using the Treasury to create as needed the t-bills used in sterilization.

JDH,

I presume the $90bn compositional change by September 2008 that you mention should be $290bn.

I wonder why the Fed are still holding over $400bn of treasuries when TSLF is only $200bn. I know the Fed do some reverse repo (like Eoghan, I find that term confusing – conventionally, reverse repo involves placing cash), but not that much. Where is TSLF on the balance sheet, by the way?

lilnev,

The dollars advanced under the reciprocal swap arrangements are effectively collateralised by foreign currency received by the Fed from the foreign central banks. I believe that dollar lending by the foreign central banks under this arrangement propogates through to the US money market and is simply offset by the Fed doing less repo themselves to compensate.

I set out my understanding of how I think the swaps work on my blog at: http://reservedplace.blogspot.com/2008/09/beware-rising-custody-holdings.html

I must say, though, that considering the potentially huge international interest rate gains and losses on this programme, the disclosure of the details of how they work has been inadequate.

It seems rather naive to say that the Fed will magically remove reserves at some future point.

The same argument was used to take FF rates to 1%. It was assumed the “insurance” could be quickly reversed. Of course that did not happen. Instead, we got “measured” rate hikes. Remember them? The idea was to proceed gently so as not to arrest the fragile recovery. Hmmm…wonder whether the next recovery might also seem fragile.

My point is that all monetary policy is easy to enter into and extraordinarily difficult to exit. Of course, no Fed official would ever admit to that.

Rebel Economist: The $90B figure refers to the increase in repos between Aug 2007 and Sep 2008.

Rebel Economist and Mark

Dionne: The TSLF is reported on H.4.1 as a $260B off-balance sheet item.

David Pearson: Nothing magical about this– the Fed can and will sell Treasuries to absorb the reserves when the demand for excess reserves falls.

Thanks JDH, I see – I tend to think of practically all of the Fed’s lending as repo, because it is generally collateralised, presumably in the form of a repo agreement.

Although I believe the TSLF remains at $200bn, the Fed also introduced an additional TSLF options programme offering $50bn more, which, with some other lending to cover shorts, presumably accounts for the $260bn. It still seems to leave the Fed with some treasuries left though.

JDH,

The Fed will not sell Treasuries to remove reserves. The Fed will have to sell what it has on its balance sheet — risk assets.

When will it be a good time to sell those risk assets? During our fragile recovery?

The Fed of course hopes that the economy will someday be able to absorb those risk assets, and not at a big loss to the Fed. Somehow the enormous balance sheets of the hedge funds, European banks and U.S. investment banks will return. Or will it be unlevered institutions (pension funds? SWF’s?) that buy the bonds back?

Good luck with that.

David Pearson’s logic seems sound.

David Pearson,

In general, the Fed does not own the risk assets. They are pledged to it as collateral by the banks to which the Fed lends in the TAF etc, and continue to be owned by the banks. If and when the markets improve and the banks’ demand for reserves falls, the Fed can simply let the repos roll off, and the risk assets return to the banks. Only if the banks go bust does the Fed end up owning the risk assets, and even then, because of the haircut, at a lower price than they were valued at when transferred.

Thanks, Jim, for some very eye-opening statistics!

You write,

I guess then I would be one of those you regard as not knowing what they are talking about. Unlike 2001, there is no reason to think banks will return these new reserves to the Fed at the first opportunity. Rather, they will, as usual, try to lend them to customers who want to purchase goods, meet payrolls, buy houses, etc, with them. This puts upward pressure on prices that would not otherwise exist, pushing inflation above inertial expections, which I estimate to be about 4.3% (Adaptive Least Squares simplified AR(1) inertial estimate for the coming year’s CPI inflation, based on the last 12 months’ inflation, continously compounded.)

Admittedly, one new technical factor is that the Fed is now paying interest at 75 basis points below the FF rate target on these excess reserves. It is true that this will make banks in less of a rush to lend them out, but lend they will, and eventually most of this base will drain out as zero-interest currency, which does have a clear-cut wealth effect and therefore inflationary impact.

One could hope that the base would take care of itself, if the Fed were following a Taylor rule with strong feedback from observed or inertially forecasted inflation. However, since the Bernanke Fed has now completely cast the Taylor rule aside, inflation accelerating above last year’s 5.2% should be a grave concern.

You continue,

Actually, it would seem to me that this account leaves Paulson’s gun cocked and reloaded to pass out benefits to favored recipients, since it is he who is sitting on the account that the Fed has obligingly opened for him. The Bernanke Fed has evidently abrogated its independence from the Treasury as well as abandoning the Taylor rule.

All this might be less alarming if there the functioning of all the new “facilities” were transparent, but that is not the case. Even if this were only a one-time increase in the base, it would still forebode a one-time increase in the price level. But since the market’s demand for underpriced put options is essentially unlimited, there is no reason to expect this to be only a one-time increase.

— Hu McCulloch

Econ Dept.

Ohio State Univ.

(The 2001 base spike was, according to Steve Cecchetti, primarily due to the fact that the Bank of New York, which was acting as third-party custodian for most Repo transactions, was across the street from the World Trade Center, and hence was closed for a few days. As billions of outstanding Repos were routinely repaid, massive reserves were duly credited to BONY, who had no way of recycling them as customary. This is a totally different situation than today’s.)

Hu, my understanding is that the Treasury Supplementary Financing Program is entirely separate from, and in addition to, the $700 billion bailout/rescue package. So I believe that Bernanke and Paulson each have their own separate bazookas cocked and loaded. The Treasury announcement of the Treasury Supplementary Financing Program to which I linked is dated Sept. 17, whereas the initial Paulson bailout/rescue package was voted down by the House of Representatives on Sept. 30.

Professor,

Great topic and discussion

If I can sidetrack a little, and ask a question, what if the fed bought toxic assets and shares in troubled institutions, as part of monetary policy and stabilisation plan, bypassing the treasury altogether, what then?

I understand the risk would be all on the fed, so if the value of these assets decreases it would end up with the potential to be even more inflationary. Do you share the view that part of a policy prescription to deal with the current crisis could includes the fed buying troubled assets and targeting a higher rate of inflation?

Jim Kapsalis, you can separate the question of which assets the Fed buys from the question of how big its total holdings of assets become, that is, you can separate the question of whether the Fed buys toxic assets from the question of whether it creates new money and thus inflation. I continue to believe that the key danger, if the assets the Fed acquires become nonperforming, is not inflation but instead a decline in the receipts coming into the Treasury.

Maybe someone here (professor Hamilton?) can explain something to me. I understand how the fed/treasury create and control money supply. I am not one of those who “don’t know what they’re talking about” with the monetization of debt.

What does concern me, and I am hoping you can address, is a little line that has appeared on the Fed’s H.4.1 release in section 6 “Collateral Held Against Federal Reserve Notes”… this has always (that I have seen) been only Gold, Special Drawing Rights, and US Treasury/Agencies. Starting in the October 9th release, there is an additional $281 billion of “Other Assets Pledged” backing the notes. This mystery collateral is concerning, since I am guessing it is some of the junk shoveled into the discount window and their other new programs. Yesterday, that number swelled to $335 billion, or over 40% of the pledged collateral.

Money quantity is the perpetual red herring of inflation, but isn’t collateral QUALITY really the culprit? Isn’t the Fed taking on collateral of questionable value and then backing the money base with it really the inflationary concern here?

Thanks,

KRE

Isn’t the bottom line of this interesting discussion of modern financial engineering just massive fiat currency debasement?

Updating the table with a fourth column for the month of October might be welcome. Another day, another lending facility…

And thanks very much for your explanation!

This was a great piece; the charts are very descriptive for all.

Not inflationary

With respect to: Anyone who suggests that last week’s ballooning reserve deposits represent inflationary pressure or the Fed monetizing the deficit simply doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Maybe the action itself is not but I don’t think there is a person in the country who does not expect to see elevated costs of goods this time next year. We have never seen the printing presses hit this hard before in the US, that can’t be good for the value of the dollar.

The dollar is a liability

I loved your description of the dollar; few seem to understand the dollar is a debt in and of itself to the FED and therefore a liability to the tax payers. The only thing that unnerves me and I have yet to see anyone write a reassuring piece on is FIAT currency.

All fiat currencies have failed

Historically fiat currencies have an abysmal track record, all have failed. Gold and silver have always been returned to. At least with a gold standard you know where zero is, when you run out of gold you know you are out of gold. The dollar has lost value terribly and people don’t realize it because there is no calculable or quantifiable way to measure people faith in the US government (I might suggest it’s not doing too good today).

The Dow has been falling since 1999

The Dow for example has been in a bear market since 1999 when compared against other asset classes as Michael Maloney. The Dow only looked like it was going up because it is measured in dollars, when you compare it against things like agricultures, industrial metals, commodities, and precious metals like gold it has been falling. In 1999 if you sold one share of the Dow you could purchase roughly 800 barrels of oil and before the big slide started you could purchase only 100 barrels. This is true for all the above asset classes listed.

Maybe it’s time we took along hard look at fiat currency

Faith in the US Gov’t — all that we need to do is buy Canada, retire all Canadians, put all the US unemployed to work at the Coal Sands, and the US will prosper mightily once again. Sure, there’d be some adjustments needed at the Fed but those liabilities would quickly be resolved.

Thank you, I am not an economics major, just the average person. If I had enough money to back just one economics class I would love it. Loved your statement. Poor but American and proud to be it. Don’t worry, we will get it together.

Vegas-

You are right, the dollar is a liability of the Federal Reserve. But I think ‘fiat’ currency is a term thrown around a lot and confuses many people (myself included). The dollar actually is not worthless paper only given value by people’s imagination. It is backed by the assets of the Federal Reserve.

Many people think that the Fed fires up a ‘printing press’ and just manufactures inked paper when needed, but every dollar, in fact, represents a claim on the Fed’s assets.

Every Thursday the Fed issues its weekly balance sheet. You can find the most recent one here:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/

Item 7 shows the collateral assets held against federal reserve notes. This collateral includes gold, US treasuries, and other assets. (my original post was a concern over the value of these ‘other’ assets)

Now, one cannot redeem a dollar for a porportional mix of these assets or pure gold anymore, but that does not mean the currency has an arbitrary ‘fiat’ value.

So actually, our currency IS fully backed by assets of equal value, but it is just no longer convertible into those other assets, like gold.

I was at first, a little confused as to how the Fed could back dollars with dollar debt (treasuries)..but my understanding of this is that the open market bidding process that sets interest rates on Treasuries is what gives 1 dollar of treasury debt the value of 1 dollar. So in a sense, the free market interest rate setting of treasury bills is the relief valve to the snake eating its tail. If I am off base here, I am sure some of you will tell me!

This is also my understanding of why an independent Fed and Treasury are critical to the currency value. The Fed and Treasury colluding to fix interest rates on government debt at sub-market values would corrode the value of the dollar. Also a reason why I am a bit concerned lately at how chummy the Fed and Treasury have become, and how Paulson totally dominates little Ben.

Should there be deeper concern about the complexity of all this? At some level, complexity seems to create situations that are prone to failure. After 4+ decades working with computer software, I distrust anything that’s very hard to understand. Even when complex systems are decomposed to simplier components, the interaction of many components can produce surprises. The suspicion of excess complexity is supported by the protracted debate over these agencies, the agents they use to manipulate, and the words used to describe what they do. If it was not excessively complex, there would not be so much debate. We are not talking about building and operating a supercollider, just managing money. Did complexity not add greatly to the recent surprises in the financial markets.

There’s much talk about the need for transparency, and complexity is a clear opponent to transparency. No matter how much regulation, cooperation and publication there is, too much complexity prevents understanding.

To Don M,

I believe your statements: “just managing money” is a strong understatement of the underlining problem.

This is something that happens to anyone that is to an extent an outsider to a topic, so I am certain you have had experiences with users of your programs thinking that the software could be buiilt in 1 week (while you probably spent years on it). An off-topic curiosity: the movie Madagascar 2, took 500 people on the making that worked for 3.5 years. And that was “just to do a movie” and not to operate a supercollider.

In addition to this, economics is arguably the most complex social science. To it you have to add Financial regulation, politics, laws, different countries very interconnected to each other, different taxes, limited resources, wars and infinite other important variables. All of this in a system composite of millions of free people, businesses and governments who act at the same time with their own ideas, expectations, fears and limited knowledge. I believe the true complexity of this vastly excedes our mental capacity.

I believe we are not clever enough to understand the underlining problem. No matter how many or how good the economists and specialists are.

Admitting this, I think we should give less power and drastically reduce the central banks and its control of money supply (maybe just a very slow continuous increase) and also leaving interest rates decisions more to the markets, just because of our limits and not for the reasons put forward by the “Austrian School”.

I believe this could lead to more long-term benefits. In this matter I prefer what the ECB is doing at the moment compared to the FED. I believe in Europe the cost of this crisis will be paid now short-term, while USA with heavier FED and state intervention is risking to pay this in the long-run. But here again I am limited to my predictions, and many people in this thread showed a much greater understanding of the problem than mine.

So keep the comments coming..

i don’t know why the author goes on and on….all the TAF, AMCLF and other F’s seem mostly funded by the “Treasury supplement” which is T-bill sales….seems pretty clear cut….i don’t know what teh rest of the article is blabbering about.

“The Treasury Department announced today the initiation of a temporary Supplementary Financing Program at the request of the Federal Reserve. The program will consist of a series of Treasury bills, apart from Treasury’s current borrowing program, which will provide cash for use in the Federal Reserve initiatives.”