How you think we might get out of our current economic problems has something to do with how you think we got into them in the first place.

Let me begin by noting several remarkable trends that accelerated dramatically over the last decade. The first is a steady decline in the saving rate, which actually became negative briefly during the phenomenal debt accumulation of 2005.

|

The second is the climbing ratio of household mortgage debt to GDP.

|

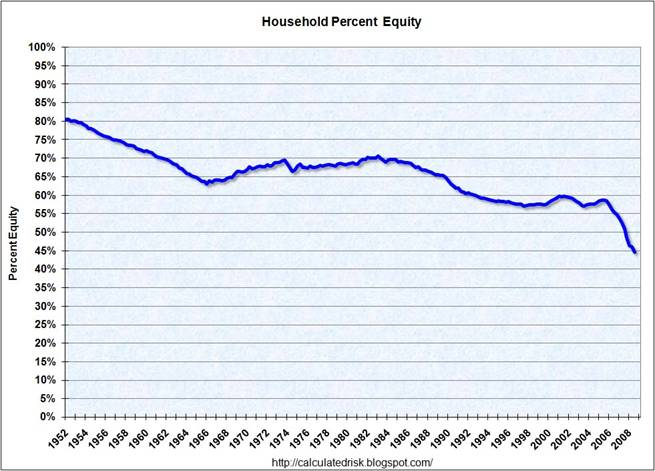

The third is the drop in the equity stake of households in their homes.

|

What caused these dramatic changes? Certainly one factor that contributed to the trend in all three series over the last decade was the extension of bigger mortgages to households that traditionally would not have qualified. For example, Ashcraft and Schuermann (2007) noted that of the $2.7 trillion in new household mortgages that were originated in 2005, 22% went to subprime borrowers, 14% to alt-A, and 21% to jumbo loans.

Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in 2007 attributed this increase in access to mortgage borrowing to technological improvements in the lending process:

the expansion [in subprime mortgage lending was] spurred in large part by innovations that reduced the costs for lenders of assessing and pricing risks. In particular, technological advances facilitated credit scoring by making it easier for lenders to collect and disseminate information on the creditworthiness of prospective borrowers. In addition, lenders developed new techniques for using this information to determine underwriting standards, set interest rates, and manage their risks.

Presumably one of the things we can agree upon today is that Bernanke’s analysis on this matter was incorrect. These new loans weren’t smarter and better, but stunningly stupid. Here’s the characterization I offered in 2007:

mortgages with no downpayment, negative amortization, no investigation or documentation of the borrowers’ ability to repay, and loans to households who had demonstrated problems managing simple credit card debt.

Why does this matter for what we do next? One view of the current situation is that the core problem at the moment is that consumers are too frightened to spend and banks too hamstrung to lend. If that was your view, you might think that the goal of policy is to spur households back into borrowing and banks back into lending. But when I look at the three graphs above, my reaction is that it’s neither feasible nor desirable to return to the ratios as they stood in 2005. The low saving and high leverage that we saw in 2005 were an anomalous departure from the likely sustainable steady-state values, and there will be no road that leads back to those from here.

If that’s the case, then resuming economic growth requires replacing spending on consumption and residential fixed investment with nonresidential investment and net exports. But charting a course for how to get there is profoundly challenging– what firm would want to invest in the current environment, and which country is in a position to increase their purchases from us?

So Plan B, at least in the interim, would seem to be an increase in the fraction of GDP devoted to government investment.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

housing,

savings rate,

subprime,

credit crunch,

mortgage crisis

I totally agree with this post, up until the last paragraph.

I’m coming to the conclusion that the idea that the effects of this downturn (and the adjustments it will force on us) can be mitigated by replacing unsustainable household spending with unsustainable government spending is as fatuous as Bernanke thinking that lenders have found a magic method of giving out ever greater amounts in subprime loans with decreasing amounts of risk.

This seems to be an article of faith among economists, but no one seems to be able to offer any proof that massive spending programs provide a way out for economies thrown into crisis by their over-consumption.

Over the next several months, it will become increasingly obvious that the world isn’t simply facing a downturn in demand born of too much caution, but there is a real over-supply of production, as well as consumption.

Increasing our deficit to 150% of GDP isn’t going to achieve anything other than binding future generations to our folly.

I share your sense that a large change in consumption / savings behavior is underway–and was inevitable–and that view is consistent with the inability of monetary policy to revive spending and prevent a deep recession. But given that view, is it realistic to replace all of the decline in consumption spending with government investment? Isn’t it possible that we’ll have to settle for a lower growth path? And even if one’s view of potential GDP hasn’t changed, won’t the attempt to substitute hundreds of billions of new government spending for the hundreds of billions of consumption that has disappeared inevitably lead to incredibly bad resource allocation? I mean, at some point don’t we have to give up the objective (at least in the short run) of getting aggregate demand back to the level that it would have been if the slowdown hadn’t occurred?

First, In my view, government spending on infrastructure isn’t “consumption” type spending, it really is investment. I called for government spending during the clinton years when we thought we had a surplus. Now, is just as good a time to invest in what needs to be fixed to forestall greater expenditures if we do not do the repairs that need to be made.

The consumer has withdrawn from the market, or has he? GM has lost 30% in sales, but so too has Harley-Davidson. It isn’t the case where Harley doesn’t know what it’s customer wants.

Harley’s 30% drop in sales is caused by the “Banker’s Recession” we are currently in. If banks aren’t lending money, you can’t buy your motorcycle, or your GM truck.

Spending to encourage energy conservation and put some real money into battery tech to allow the US to lead in an EV revolution and plan to have a US Battery manufacturing industry should also be helpful for avoiding future economic failures caused by Global Warming.

Hey Brainwashed US public! If you stop all immigration for 1 year you’ll save 1.5 million jobs!

Duhh…bringing in worker’s for nonexistent jobs, produces more unemployment!

But of course, you cannot even comprehend such an approach!

Since the Anglo-American countries are exceptionally good at CONSUMING the logical conclusion is to continue the consumption game with one exception.

Bernanke and Hanky Panky must supply time coupons or a Gesell type currency to every citizen who commits to doing their global duty of consuming the worlds excesses.

Extra coupons should be given to those who “go beyond the call of duty” and make a permanent commitment to shop “in sickness and in health”.

The one chart you missed was the great debt bubble we have been blowing up for the last 30 years.

Our aggregate debt is now over 50 trillion, more than 3.5 times GDP.

The current mess has popped that bubble …

Have a look at this chart …

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2008/07/has-deleveraging-even-begun-not-for.html

increased savings and comonsensical consumption would lead only to european economic malaise: slow economic growth, higher unemployment, less time at the mall, more spent on education, social unrest on any sensitive subject, fed policy that protects the value of money….

how does all this fit into the agenda of the present feudal political class?

Hey, Mike. I need 130 tomato pickers in April and May. Pay is $7.45/hour, no benefits or health care. My neighbor also needs 15 roofers to tack down shingles on third-floor roof in Austin, where the McMansion boom is still going strong, in late July through September. Applicants should bring their own hats, sun-screen and water bottles. Pay starts at $9/hour, but can go to $11 for those who will work hard as the Mexicans. Want a job? We need American workers. Come on down.

If economists learn anything in the last eighty years, we would not be staring over the precipice of another depression. I have no confidence that our leaders can stop our fall, especially given the massive credit damage has already be done.

I refer to your last paragraph suggesting replacing consumption and residential investment.

What you are saying is that you fundamentally would like the US economy to be the German economy. Germany and the US however have very different fundamental characteristics.

German consumption growth has been miserly for many years now. One of Germany’s wise men explained to me the reason for this in his view over 15 years ago: Germans already have several TVs in their living room, bedroom, kitchen; should they buy TVs to install in their bathrooms? In other words, his view – typically German – was that German consumption needs were fundamentally satiated. And, certainly, the fact that the German birth rate is extremely low and that population is stagnating and on the verge of decreasing must have something to do with that. The US on the other hand exhibits strong population growth, from birth rates and from immigration, legal and illegal, you name it.

Similarly in terms of housing and residential investment, the German population fundamentals do suggest that their needs are rather on the low side in this area too, whereas US needs fundamentally are higher, even if they do not extend to the need for a McMansion for all on the San Diego waterfront.

My view would thus be that the US will remain a debt-driven economy in the long run. In the short and medium run (1 to 4 years) however, the excesses since 2000 do need to be reversed: households need to increase their saving rate and keep it reasonably positive on average. Borrowing from the rest of the world, which will remain inevitable, should fund useful purposes, be it research and development, improvement of productive capacity for goods and services including public infrastructures and so forth. For sure, capital will remain attracted to the most advanced economy in the world as long as that economy remains hooked on innovative developments for the future, ie as long as your country keeps bringing out the T. Eddisons of the future.

I AGREE

Prof Hamilton,

I agreed with your analysis. I guess, perhaps, the Fed is trying to engineer inflation – thus, reducing debtors burden and depreciating the dollar to gain competitiveness in exports. It is risky if the dollar plumets and investor (both foreign and american) took fright. Suppose the Fed can drive inflation to 5%, the dollar exchange rate fell somewhat and investors accept negative real interest rates (as now) then in some years US debt burden can become more manageable.

Tyler Cowen has the answer: spend less, save more, be poorer (for a time).

It’s called austerity. It is a legitimate response to the economic challenge we face.

And I agree that exporting more is part of the solution. Part of saving more is that the dollar must fall against competing currencies. The runnup in the yen is a good thing, then.

Professor Hamilton, you may need to spend more time working in the government before you post paragraphs like the last one. When you can explain to me how money pits like the DoD’s Joint Tactical Radio System or the monstrous growth in real per-pupil spending in the Department of Education have been a good allocation of resources, you let me know.

It’s like economists think there’s a different set of rules once you get to the national, governmental level of the economy. Is it a good idea for a person to blow their money on a sports car he can’t afford? No. Is it a good idea for a family to buy a big screen TV it can’t afford? No. Is it a good idea for a company to throw a lavish Christmas party it can’t afford? No.

Somehow, it’s a good idea for a government to simply blow money on absolute rubbish it can’t pay for. We’ll all be better after that.

Right.

Your analysis overlooks the known phenomenon of overshooting. Risk, underpriced for most of the decade, is now overpriced, as various spreads demonstrate. For example, the lightning-fast contraction of auto financing is a major factor behind the collapse of the auto industry. While some of that financing had been subprime in nature, not all of it was, and for months lenders have been refusing to originate loans even to good risks. So, yes, part of the solution will require getting consumers to borrow and banks to lend again–but at normal as opposed to reckless levels.

How to do this? Trust is now gone from the marketplace, and it must be restored.

Clear and simple. Thank you.

While American households clearly ran amok earlier this decade, stacking up debt well beyond their ability to pay, I think this article covers less than half the story.

The other–and, in my mind, more important–driver in our current economic crisis was the the hyper-leveraging of this debt (especially mortgages) by American banks. Under no circumstances can leverage in excess of 30:1 (and sometimes 50:1) be deemed prudent, not even on the absurd premise that home values will always increase. This grotesquely irresponsible leveraging of debt has caused the massive liquidity crisis–and the recession–we now face.

In these circumstances, I believe it is folly to continue Fed or Treasury aid to these highly-leveraged financial institutions. They are merely supporting a financially crippled, cancer-ridden banking system. Instead, they should be injecting liquidity through “good” (low leveraged) banks that are capable of actually lending it rather than “bad” banks that simply use it (so far, unsuccessfully) to shore up reserves. (See GS’ quarterly report today.)

“How you think we might get out of our current economic problems has something to do with how you think we got into them in the first place…”

Please forgive a naive question, but: Did we really do anything “wrong”?

In the first chart (personal savings as percentage of disposable income) the dramatic fall since 1980 coincided with an equally dramatic fall in interest rates. So has what’s happened been the result of some lapse in fiscal or moral responsibility, or was it simply a rational response to the fact that the rate of return on savings has been falling for decades?

And the same argument for the increase in debt. If it’s an axiom of economics that the cheaper you can sell a thing the more of that thing you’ll sell, why isn’t a higher level of debt simply the rational response to cheaper money (lower interest rates)?

It’s an easy thing to make the argument, heavily freighted in morality, that we brought our current predicament on ourselves, but our behavior has been similar for decades. Sometimes we brought “bad” times on ourselves, but we also brought “good” times with similar behavior. So what was the difference?

Not an apologist for Alan Greenspan, but he makes a valid point when he says bubbles are tough to identify and deal with in real-time, because they’re only “obvious” after the fact and tough to distinguish from simply higher levels of sustainable growth.

Sebastian

Nice analysis. China just allowed flights from Tiawan. No reason USA shouldn’t do the same is a very minor stimulant. I can see why you’d not want to trade with nations proliferating nukes or housing asymptotic warfare schools, but Cuba? C’mon they nationalized assets five decades ago and Castro has been subject to hundreds of failed USA assassination attempts. Call it even. Cuba’s strength is healthcare and sustainable agriculture. The former is USA’s weakness and the latter the developing world needs.

Over the long-term you wanna encourage R+D and good public schooling…some short-term stuff is obvious: tax the rich until the masses see some pre-Reagan levels of income growth (as opposed to contraction since 1980), bolster employment intensive sectors. When the banking industry loses trillions, I can’t see how the beauracracy of Crown banks would be more expensive until some *time* and effort is devoted towards learning how to screen out derivative ponzis.

A reflexive tipping point is that at some debt level (my guess), capital flight will occur inducing inflation/depreciation. Capital comes to USA because other markets don’t have mature financial systems but at some level and endless deficit will be seen as more risky than corrupt stock exchanges. If this occur you need an immediate plan B that is almost the opposite of plan A as I wouldn’t expect the capital to come back.

What can you do with big housing glut? Turn them into daycares? I like the idea of grow-ops and brothels.

Which is a higher quality credit, a note to a subprime borrower secured by real estate collateral, or an unsecured small business loan?

How many borrowers could have qualified for a prime conforming loan, but instead opted for a (larger, cheaper, though more speculative) subprime product? How much subprime production was invested in real estate versus other pursuits (equity investments, capital equipment, business development), and how much was simply consumed?

How much subprime lending was to low income and other credit challenged borrowers?

Unless and until you can really answer these questions, you will not understand the origins of the credit crisis….

How about an alternate summary of those nice charts: Americans have borrowed furiously for several decades, and while for some of that period the investment yield was sufficient to cover the debt service, in very recent times the return on the committed investments has faltered with respect to the debt service, leading to a severe crisis.

The problem was and is not only accumulation of debt, but its malinvestment. Had business, personal and government debt been used to increase wealth say in the form of funded pension plans, universal medicare, infrastructure maintenance, energy efficiency, research and development etc., we would be wealthier than we are now. These investments represent a form of national savings and would appear as assets on the national balance sheet.

There is no choice to but to borrow and spend /inflate our way out of this depression…this solution will work only IF the money is invested to create wealth. It will not work if it is thrown at losing propositions, which is only a denial response to the reality of bankruptcy.

Dr. Hamilton- While the run-up in consumer leverage has contributed to the “credit crunch”, I am dismayed that you have ignored the cause rather than the effect… I submit that the cause was liberalisation in reserve requirements promoted by the BIS’s Basel 1 and II Accords. I would suggest you read Sheila Bair’s June 2007 speach on this subject…

SHEILA’S SPEECH

While it took expensive lobbying for many years to implement regulatory rule changes, the international banking cartel has been successful in: Transferring its financial risk to government, Shaking-off regulatory oversight, and Looting earning of the private economy far into the future.

please explain this to Mr Krugman and his friends.

@L. Pelon: if that’s all you’re paying, the work you want done must be of negligible value. So as far as I’m concerned, those tomatoes can wait … forever. (And as for any need anywhere for yet more McMansions, well, ROFLMAO.)

Maybe you need to grow something more productive or less labor-intensive. Whatever. But the rest of us are already in enough economic doo-doo even without having to subsidize you by covering, with our taxes, the difference between the risible pittance you and your neighbor choose to pay, and what it actually costs to survive and make oneself available to work for you.

I agree with the first comment.

I think a big part of the problem was current account surpluses from China and Japan, kept artificially high by direct currency intervention (China) or implicit promises to intervene (Japan, which removed currency risk and greatly expanded the yen cary trade). The lending had to go somewhere. No matter how egregious the loan practices in housing, the net amount loaned cannot have exceeded the net saving available. High leverage and bad lending practices could have misallocated available saving, but could not have increased overall debt levels.

Dr. Hamilton, I have one little problem with: “So Plan B, at least in the interim, would seem to be an increase in the fraction of GDP devoted to government investment.” There has already been incalculable government squandering and I certainly expect vastly more, but calling it investment seems like a quintessentially Clintonian circumlocution. After all, it nearly always denotes stuffing the pork barrel – think Turbo Trains (designed for high speed on the flats) creeping up the West Virginia hills at 15mph, or expensive freeways to nowhere in the northern-plains empty quarter – with zero prospect for the future returns one expects from “investment”.

James, a hypothesis that is consistent with almost all the facts you present is that real wages have been declining. How that is, I don’t know. We’ve talked about the measurement of inflation, and Greenlees and McClelland is very persuasive, but there are other ways that mismeasurement of real wages could occur. For example, every time that a person has to re-locate, there are associated costs, not all of which can be recaptured. So a rise in labor mobility could be associated with a declining living standard. Also, for the median family income to rise, women have been forced to go to work. Perhaps there is mismeasurement of the economic value of their uncompensated labor.

There’s a tendency to see the present generation as somehow inferior (e.g., lazier, e.g., less entrepreneurial). But I don’t see that. Past generations were wracked with terrible problems, including the fact that we excluded two-thirds of the population from the talent pool from which we drew. The present generation has been less able to claim its share of productivity gains. That seems to me to be the place to start the examination. Are people saving less because they have less to save?

It seems more plausible to me that the US must endure a period of lower consumption and higher investment to get back on track. Since we over consumed for the past 30 years, we face a period in which we must under consume.

I don’t have much confidence in the ability of the government to wisely invest the money. Perhaps Charely Rangel’s son works for a good investment firm or we can get Rod Blagojevich cut some deals.

Dear Professor Hamilton,

Can you define government investment (the last term in your post)? Thanks.

Dr D, I’m just going to assume the subprime lender used the credit as collateral for some sort of fraudulent pyramid scheme while the business loan is limited liability and of higher quality credit.

I’m not trying to understand the origins of the credit crisis at the moment. Just trying to figure out how to sop up impending unemployment. Right now the best the well-paid finance minds can figure out is to give derivative cowboys more cash to play with without enacting any checks or rules on preventing this scheme from replaying. I’m suggesting enacting public banks in the hopes the efficiency losses from no market price signals outweight the gains of pyramiding credit to make derivative/leverage gambles that are all profit and taxpayer losses, until better derivative/credit regulation are drafted to prevent this from happening again. Feel free to suggest an alternative.

You’ve attacked small business subsidies, feel free to suggest an alternative. The world is waiting. Leaving people unemployed is more expensive than subsidizing crappy small businesses. IDK where the point of inflection is where a small business subsidy becomes more expensive than unemployed workers….but the standard Keysnesian refutation of Say’s Law that you need to get an unemployed worker, work, before they can create spillover demand, is true.

Can big homes be cheaply made into nursing homes? That might sop up demand for too much housing stock in a few years.

Sorry, Dr.D. I didn’t even suggest small businesses on this thread; confused this with another blogversation.

Well, one thing is sure. The FED just took us on a retro ride. Welcome to Japan.

Professor,

I have to admit that you really had me going. I am reading along and your post is absolutely wonderful. You even point out that Ben Bernanke has been absolutely wrong about the economy and I am really getting excited then as the climax comes I read, “So Plan B, at least in the interim, would seem to be an increase in the fraction of GDP devoted to government investment.” Suddenly I feel like I am in the middle of one of those jokes about a man in an insane asylum who seems sane right up to the punch line.

Increase the fraction of gdp devoted to government investment?! You have got to be kidding!

joeboy, government investment is as defined by Keynes. It means the government should take your money and spend it as they desire because they are much much smarter than you are and know that it is better to pay a man to pick up trash in a National Forrest than it is for you to buy food for your family. Get real man. By definition, anyone who works for government is suddenly a genius his first day on the job.

On a more serious note, whatever happened to trusting people? It is the people who know how to invest and produce the goods that help other people. When are we going to realize that taking money from the producers, the average guy, and giving it to fat cat failures is a disaster. Whatever happened to letting failed businesses fail? When are we going to come out of this fantasy Keynesian world and let our economy prosper?

Phillip,

Actually, I’m pointing out that a large amount of subprime production went to financing all sorts of small and home-based businesses. In the aftermath of the dot-bomb, small business loans became much more difficult to get, but loans collateralized by real estate (cash-out refi) became much easier to obtain.

Was that a “stunningly stupid” decision on the part of lending officers?

Further, if you compare individual ABS/MBS transactions (entire ‘deals’, full capital structure) with a stand-alone bank, are the ABS/MBS securitizations worse? The securitizations are fully transparent and hold high levels of reserves….

There are two forms of work, labor and mechanical. Growth happens on the margins, that is it only happens when the supply increases. The capacity of labor is dictated pretty much by population growth. It can be enhanced by increases in mechanical work. That demands an increase in efficiency (which usually requires capital) and energy supply. You basically can’t have growth without energy supply growth. Unless people increase their energy production, we’ll be in a state of people fighting for a bigger piece of a smaller pie.

Aaron, the paper: “Source of economics growth..”, ideas.repec.org/a/aea/aecrev/v92y2002i1p220-239.html

…suggests economic growth in the USA has occured via better education in the USA (30%), spillover from other nation’s R+D (50%), and then only weakly (10%) from population growth. I’m only on pg 4.

Dr.D I do think ABS/MBS were stunningly bad. Consumers would have more savings now and USA would have less federal debt and face less future inflation/devaluation if not for those vehicles. Mild unemployment 2001-2008 and crappier homes now is much better than *trillions* of debt. I can’t see a safe way of transitioning from deflation to inflation that ensures unemployment stays single digit. Probably you could invent a novel derivative vehicle but all those best minds are trying to get paid instead of averting unemployment over the next decade. You can’t have loans on top of a loans and expect pre-derivative post-WWII financial institutions to function. I’m assuming the odds of USA hyperinflation just went from 10% to 30%. Prolly not so bad if you don’t assume the same.

I’m still fascinated by the ideas put forward by this article: http://www2.nationalreview.com/monetary.html which suggests, among other things, that the US political class has an interest in maintaining and expanding the trade deficit because it allows them to issue lots of government debt, which they then get to spend. The authors make a seemingly convincing case (to this amateur crisis watcher) that the resulting foreign ‘hot money’ dollar holdings play a decisive role in the creation of bubbles and the crises that follow them.

I have yet to find any published criticism of this article, and it would be interesting to see what ‘you all’ think of it.

Joeboy: I’m defining government investment as government purchases of structures and equipment, including for example mass transit, port facilities, schools, hospitals, prisons, bridges, and transmission lines.

Thanks, sounds interesting.

Novel derivative:

The idea is to go ahead with foreclosure or make the occupant sell the property. Part of the loan is paid down. The bank can then collateralize the remaining portion of the debt with properties it is unable to sell, preserving the value of these properties and incentivizing pay off of the remaining debt. It could quickly reshuffle the existing housing inventory.

It could be made to work by creating a housing lottery and not actually giving the liability holder an actual property, but a different asset which can be used to buy lottery tickets for certain property classifications.

It could possibly match potential buyers and seller more quickly than foreclosure auctions. The chance element eliminates the need for the buyer to do extensive research or be familiar little know forclosure markets.

Tickets can also be sold and bought for cash.

you have got to look at the direction of central bank interests over the past 20 odd years as a key element of the problem.

although i agree banks were lending willy nilly the cost of capital was so small the interest rates for personal loans and mortgages had to fall meaning more people willing to buy homes and a house price bubble.

if you look at economies with stable central bank interest rates their economies are not being as poorly affected as the US and UK.

as a result of this i think that central banks need to look at maintaining stability in interest rates and maybe letting inflation float a little.

just a thought.

After thinking more about it, the problem with the last paragraph is this. The stimulus spending bills being discussed are not investments. That is, they will return absolutely nothing. Roads and bridges may need repair, but that’s maintenance, not new construction. You can look at Google Earth and see that there is nowhere in the country that you would want to go that you cannot drive to right now. No new capabilities will be created; no new business opportunities will come from it. Ergo, this will produce absolutely zero ROI.

Education spending is an even worse idea. We passed the point of no ROI long, long ago. Test scores and dropout rates do not respond to additional spending because it’s a cultural problem due to the breakdown of the traditional family. All of that money is wasted.

Bailing out states who have mismanaged their budgets guarantees future mismanagement. That’s got a negative ROI.

Which leaves us with what as a true “investment?” Changing light bulbs to CFLs? Just wait until you get the bill for the hazmat cleanup of broken CFLs.

This isn’t an investment at all. Like the German finance minister said, this is just a pack of politicians racing to pour billions down various ratholes in a search for the Great Rescue Plan, which does not exist.

The trade deficit contributed to the 28 year growth of our current problems in three ways: 1) keeping down inflation because increase in imports reduced costs of goods sold; 2) Keeping down wages in manufacturing by forcing workers to compete with low wage workers overseas. 3) Shifting the source of profit creation in the U.S. from manufacturing to finance.

New policy needed – to reduce the U.S. trade deficit in half in 3 years.

I side with those who think borrowing and spending by the government is bad – for the next 6 to 9 months. Banks and insurance companies that have made bad bets should be allowed to fail. Bernanke and Paulson’s actions should be repudiated. No more bailouts – try to get some money back from AIG and Citigroup.

After mortgage defaults cease growing and the financial system has been cut in half will be the time to add government investment – carefully.

“there is nowhere in the country that you would want to go that you cannot drive to right now.”

This is pretty much true, but there are places where there is oil and other resources to be extracted that you can’t drive too yet. There are places where capacity can be increased, intereference can be eliminated (replacing interesections with roundabouts or overpasses). And places where technology can better manage traffic. Efficiency can be improved with research and an informational campaign to get people to accelerate faster, avoid braking (by easing off the accelerater earlier), etc.

Good points Aaron, but that seems like pretty slim pickings in exchange for hundreds of billions of dollars. You could probably get the same results without any stimulus bill at all just by rolling the education budget back to 2001 levels and putting that money into roads and bridges.

KTCAT I’m with you on roads and bridges, the rest of the post is nonsensical. America’s public primary schools are an underfunded joke.

Broadband internet, highspeed rail, building retrofits, public transit,..etc, all return more than higher property and violent crime rates of an unemployed population.

Just to always be a contrarian, we could also use a couple more bridges to Canada. Of course, capacity could also be greatly increased if with more customs inspectors (multiple inspections in one line.). There could also be something like Costco’s roaming scanners, however that introduces a security weakness that would need to be adressed.

When the final analysis of the present crisis is written, I wonder how much blame will be attributed to the anti-government prejudice expressed by people like DickF, PaulS and KTCat? If the US government had intervened to direct the reserves capital inflows into either building America’s infrastructure or its own foreign exchange reserves, the US might have mitigated the boom and been in better shape to deal with the bust.

Have you any idea how daft some of the comments on this blog seem in Europe? From this thread:

“Education spending is an even worse idea. We passed the point of no ROI long, long ago”? According to James Heckman, the rate of return to pre-school education is 16%.

“think Turbo Trains creeping up the West Virginia hills at 15mph”? Try Swiss Railways.

DickF already wrote my thoughts exactly. Your subsequent explanation of government investment helps and actually makes sense. However, you don’t get to decide how to spend the money, Pelosi, Reid, Schumer, et al. get to do that so I remain depressed and will probably get more depressed as time goes on.

We are in this pickle because the government, markets and banks are over-correcting for the irrational exuberance of the middle part of this decade. Most of the problem mortgage debt is not first time buyers, it is from people re financing or moving to a larger house than the could afford. Much of the problem in the credit markets was based on the irrational belief that housing prices always go up, and that banks could take the risk out of risky loans.

Mark to market, as presently used, overvalues assets when the bubble is inflating, and undervalues them when the bubble bursts. Recessions should be called corrections, where we as a society correct for irrational exuberance. The problem comes when we over-correct, much like a driver over correcting on ice will put his car in the ditch. Speculators paid too much for things like CDO’s in the middle of this decade, but they could justify the price because of mark to market. When Merrill sold a bunch of their paper at 22 cents on the dollar, the market over corrected, because revaluing assets under mark to market rules panicked the banks. Ask yourself the question: is there a house out there that has lost 78 percent of its value? So why did the Merrill paper do that?

Financial institutions at 30:1 leverage need to lower that level, BUT THEY SHOULD NOT DO IT TOO FAST. The bubble has to be deflated slowly.

We are in this pickle because of over correction and panic.

We have failed to improve the situation because Paulsen, Kashkari and company have gotten nothing done:

1) Hope for homeowners passed in July. It took the gov’t until October 1 to really start the program. And they only got 42 applications in October.

2) Paulsen and Bernanke stampeded Congress to pass the TARP bailout, but very little of that money has actually been disbursed, according to Kashkari. Yes, you have seen the announcements, but very little money has moved. In cases where it has moved, the banks are still not lending, and Kashkari and company will not admit that you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make him drink. They do not understand how to thaw the credit markets. Paulsen and Congress expected that passing the legislation alone would reduce the banker’s panic and insecurity, and they were wrong.

3) When pressed by Congress during hearings last week, Kashkari’s responses were “We are studying this, we are writing the rules for that”, and so on. Just as in the aftermath of Katrina, these guys are incompetent at getting things done.

A lot of big time economists refuse to understand bubbles and the mass psychology that creates them and bursts them. They want it to be totally about the numbers, and ignore the fuzzy logic in the collective brain of the population.

We will get out of this when we look around, see things that need to be done, and allocate unused resources to get them done. Our infrastructure has been crumbling for years, we need to rebuild it. Because of the recession/correction, we have human resources available, financial resources available (from the gov’t) and physical resources like concrete, steel, copper, and so on, available. It just takes the leadership to get it done, and approach it like we are on a war-time footing.

When the history of this is written, historians will look at the incompetence of the Bush administration, how they made things worse by expecting markets to be self regulating, as if pulling the cops off the streets would make everyone behave. 95 percent of the population would behave, but that other 5 percent can really foul things up. We are lucky that the effects of all this are happening this close to the end of the Bush years.

And…. some historians will ask the question: Would we be better off with a parliamentary system, where leadership that is clearly failing can be replaced quickly, instead of having to wait up to 4 years?

When the final analysis of the present crisis is written, I wonder how much blame will be attributed to the anti-government prejudice expressed by people like DickF, PaulS and KTCat?

Probably close to zero. Government hasn’t exactly been languishing, you know. As for it being prejudice, I’m not sure where you get that idea. If I was running the government like a business and I wanted it survive and prosper, I would have no problem at all with the roads and bridges money that Obama has been talking about. I just wouldn’t borrow money to pay for it when so much cash is just being poured down the drain right now.

I can’t imagine how the debt is ever going to be paid down, much less paid off. The Japanese have been scratching their heads wondering the same thing about theirs after doing pretty much what we’re starting to do now.

I had suggested this idea in marginal revolution also. One could try this for recovery.

Lets say the US government understands from standard macro-economic models that it needs a trillion dollars of stimulus to prop up employment back to proper levels.

Instead of cutting this amount from taxes or announcing spending programs of that amount, announce a Trillion dollar prize, which will be paid out at the end of lets say 3-4 years (a time by which one might reasonably say useful physical/social capital can be created).

The prize will be for creating jobs. To avoid an overload of minimum wage jobs, the prize could have a minimum cutoff wage or can be based on payroll amount instead of jobs created. To avoid concentration of high paid fat cats, the prize can be given based on the multiplicative product of all salaries. This way, orgs that pay out more equally do better.

In auctions or such game-theoritic situations, you will have multiple players trying to end up with one prize and in aggregate, losing out. But here, that is what we want. We want people to spend more than a trillion dollars trying to get to that pot of trillion and voila, we have money going into the hands of people.

The advantage this proposal has is that it is totally upto the organizations to decide how they want to structure their “jobs”. All we are concerned with are salaries. No bureaucracies, no planning mistakes, no second guessing the market’s “true wants”.

KTCat,

Even if existing government activity is not as efficient as it could be, if there is a robust case that a public investment project will return significantly more than its cost of funds, it would be rational to go ahead with it.

The state share of GDP is relatively low in the USA, and the possibility that it might be suboptimally low should be considered.

Rebel, I respectfully disagree. I submit that with the help of an monstrous stimulus package that is guaranteed to fail in the long run, the government will face an existential crisis on the order of the one that Equador is facing right now as they default.

Ecuador (and Iceland and Greece and …) can default because the US exists and provides a buffer to the world economy. The US is about to just print money like mad to invest in things that cannot possibly pay back the debt. That would be OK if this was Year 1 of doing that, but it’s not. It’s more like Year 40 of doing this.

I do not believe that the politicians nor their appointees have a vision for solvency in, say, the year 2020, or if they do, they have no idea how to get from here to there.

As for the state share of the GDP being low, it’s something like 35-40% in dollars and lots, lots more in terms of regulations and mandates. That’s low in Soviet terms, I guess.

We will have to convert to a balanced economy where we export at least as much as we import,perhaps more to repay decades of balance of payment deficits. While it is hard to imagine with today’s global economic contraction, it must be so – there is no other option. In order to get there, the dollar will have to be devalued and previous export-focused economies will have to stimulate their domestic consumption demand. We were transitioning to this new equilibrium in a reasonably smooth fashion prior to the credit freeze. Now it is going to be downright ugly.

My Take-

A. 1% Interest Rate.

Kept at 6.5 no big boom

Banks rushed to borrow as much as possible.

Loan as much as possible.

Bundle Loans and sell to Gamblers.Coverup bad loans in pile.

Banks got small quick profit but had no income from assets or mortgages each month

B. Fed increased M-3 by 4000B from 2001 to 2007 or twice as much in six as prior ten.

C. Devlopers had access to low interest money.

Built homes too large-too expensive for middle class incomes

Price of average sized home increased by 68% 2001-2007 Labor/Materials did not increase 68%

D. Realtors had excess to sell. sell sell sell

Frenzy with LOW Interest Money and PLENTY of it

E. Speculators bought with no/low down payment and low payments for several years. Appreciation will be big profits.

Sone bought several houses.

23% of Foreclosures have been on Speculator purchases.

I fault 1%.

clarence swinney

political research historian

lifeaholics of america

author:Lifeaholic

cswinney2@triad.rr.com

I would like to see an active debate start on restoring a diverse, growing, and profitable American manufacturing base.

Why, for example, is it a cheaper proposition for a consumer to walk into their neighborhood discount store and purchase a $.99 plain plastic bowl that was originally punched out of an assembly line in China for under a nickel, packed, shipped half-way around the world, trucked from one of 6 major freight ports to a short list of cheap import distributor warehouses, and then to a retail shelf in any small town in the USA – …than it is for that same consumer to pay the same $.99 for an identical bowl punched out on a machine at a US factory…perhaps located in their state or region…at a per unit cost of a dime or two….is just plain embarrassing.

Hopefully, achieving competitive superiority in the plastic bowl manufacturing industry will not become the pinnacle of America’s realistic aspirations for restoring a vibrant manufacturing / employment base. But, if we can’t even compete with a factory on the other side of the world at making a plain plastic bowl that sells for under a buck that was nearly 100% made by a machine (aka: no issue with labor differentials between China and USA), then how can we begin to secure financing necessary to make larger capital expenditures to build more complex and comparable quality products and that the consumer will want to buy…that are made with more efficient machines, in more efficient factories, and with more effective techniques…to keep more of America’s dollars circulating within the our economy…contributing to our country’s tax revenue, cash in circulation, and trickle-down employment growth?

After all, what are the ingredients needed to make virtually anything in the US? Long-term Funding/financing (at favorable terms) for plant & equipment and operating expences, R&D, production and supply chain and distribution network, raw materials, skilled/specialized labor, energy, legal/patent/copyright/licensing, tax and other regulations, and a solid marketing growth plan…long-term committment to growing the business, vision, guts, ingenuity, and plenty of elbow grease.

What am I missing, here?