Today’s announcement from the Federal Reserve marks the end of the road for Plan A (fighting the recession by lowering interest rates), and the beginning of … what?

The Fed’s announcement begins:

The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to establish a target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent.

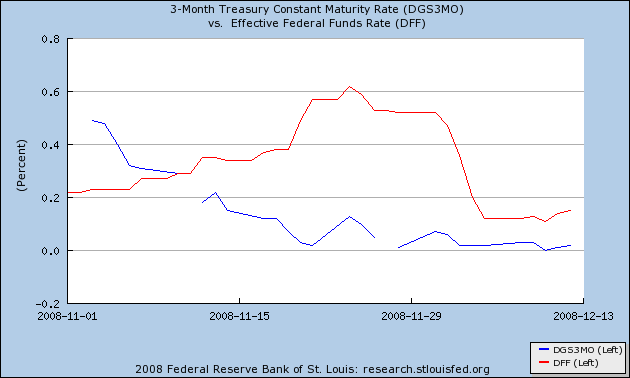

Although that caught the headlines, it’s really the anticlimactic part. The actual fed funds rate and short-term T-bill rates had been well below the Fed’s previous “target” of 1.0% for some time, making today’s announcement little more than an acknowledgement that that’s indeed where we are. At least we can all finally agree that further rate cuts from the Fed are completely irrelevant, if for no other reason than because it’s physically impossible for there to be any more ahead.

|

The main news value of the Fed’s announcement was the opportunity for the Fed to communicate what else besides rate cuts it may have in its bag of tricks:

The focus of the Committee’s policy going forward will be to support the functioning of financial markets and stimulate the economy through open market operations and other measures that sustain the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet at a high level. As previously announced, over the next few quarters the Federal Reserve will purchase large quantities of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities to provide support to the mortgage and housing markets, and it stands ready to expand its purchases of agency debt and mortgage-backed securities as conditions warrant. The Committee is also evaluating the potential benefits of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities. Early next year, the Federal Reserve will also implement the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility to facilitate the extension of credit to households and small businesses. The Federal Reserve will continue to consider ways of using its balance sheet to further support credit markets and economic activity.

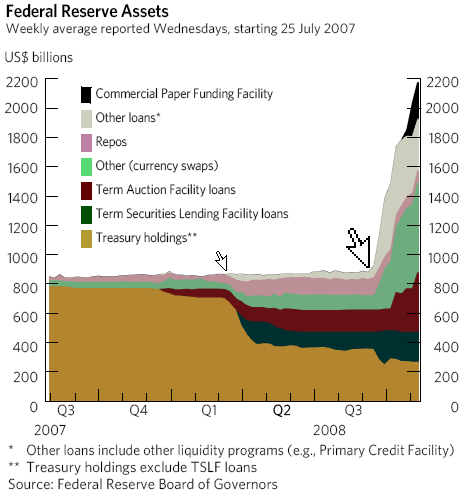

The frustration for the Fed is that while the T-bill rate is already essentially zero, term rates charged to any of the rest of us remain far higher. The Fed continues in its hope that by changing the composition of its assets– making loans itself, buying MBS– it will be a big enough factor in the demand for the less favored assets to move those spreads. This of course is exactly the kind of thing that the Fed has been doing for the last year, with the FOMC today promising an even bigger expansion of its holdings of unconventional assets.

|

WSJ reports this clarification on what the Fed intends from a press conference with a “senior Federal Reserve official”:

Is this quantitative easing? The Fed said in its statement today that it will be using its balance sheet to support credit markets and the economy. Some analysts have called the approach quantitative easing– effectively expanding the money supply once interest rates cannot be eased further– as Japan did during its economic turmoil.

But the senior Fed official said the central bank’s approach is distinct from quantitative easing and different from what the Japanese did. The Fed’s balance sheet has two sides, the official explained: assets with securities the Fed holds (including loans, credit facilities, mortgage-backed securities) and liabilities (cash and bank reserves). Japan’s quantitative easing program focused on the liability side, expanding cash in the system and excess reserves by a large amount. The Fed’s focus, however, is on the asset side through mortgage-backed securities, agency debt, the commercial paper program, the loan auctions and swaps with foreign central banks. That’s designed to improve credit-market functioning, the official said. By expanding the balance sheet by making loans, the official explained, the focus is not on excess reserves but on the asset side. That securities-lending approach directly affects credit spreads, which is the problem today– unlike Japan earlier, where the problem was the level of interest rates in general, the official said.

Will that strategy succeed if we just do it on a sufficiently large scale? I’m not at all convinced that it would. Our standard finance models treat interest rate spreads as governed primarily by fundamentals such as default risk and only secondarily by the volume of buyers or sellers.

But while the Fed may have little control over the spreads between different interest rates, it does have a significant degree of control over the inflation rate. The 1.7% drop in headline CPI during November, and the -10% annual deflation rate for the last 3 months, should not be viewed as welcome developments in an environment where our primary concern is whether individuals and institutions are going to repay their debts. The Fed should want to generate enough inflation to pull those short-term interest rates above the zero floor. But to target inflation, the Fed would take exactly the opposite strategy from that outlined by the senior Fed official above. The goal would be to get cash into circulation rather than be hoarded by banks, and have the Fed’s assets be ones that could be readily liquidated if the inflation starts to come in higher than desired.

Greg Mankiw wishes the Fed had added to its statement something along the following lines:

The Committee recognizes that moderate inflation would be desirable under the present circumstances. In particular, the overall level of prices a decade hence should be about 30 percent higher than the price level today.

And I like Greg’s explanation of why that’s the direction we need to go:

As Jim Tobin said in an earlier era, there are worst things than inflation, and we have them.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

term auction facility,

deflation,

inflation,

credit crunch

“and have the Fed’s assets be ones that could be readily liquidated if the inflation starts to come in higher than desired.”

Ut-oh. Are we setting ourselves up for something unexpected?

Professor,

Thanks for the quick post. I have a couple of practical questions and would like to know your thoughts.

Do you think all this easing and the Fed plan to do more will help to contain the second wave of foreclosures from Alt-A and prime loans that many are predicting (e.g., CBS 60 minutes yesterday)?

Also, Jim Rogers, the well-known investor, has said most of the big US banks are basically bankrupt. Do you agree?

Since:

1. The government is the country’s largest debtor.

2. The government sets the inflation rate.

3. Inflation benefits debtors.

Only the most naive dolts could possibly think that “too little inflation” will ever be a significant or sustained problem in the U.S.

“Our standard finance models treat interest rate spreads as governed primarily by fundamentals such as default risk and only secondarily by the volume of buyers or sellers”

For prime mortgages, at least, you left out the most important determinant – prepayment risk. Because there is massive uncertainty over rates there is massive prepayment risk, hence very high spreads for mortgages. Produce the event that the market fears – a drop in rates triggering a refi wave, and a main prop for the high spreads disappears, generating something along the lines of a self-fulfilling prophecy – low rates (from which no further refinancing is likely) justify low rates.

But to target inflation, the Fed would take exactly the opposite strategy from that outlined by the senior Fed official above. The goal would be to get cash into circulation rather than be hoarded by banks, and have the Fed’s assets be ones that could be readily liquidated if the inflation starts to come in higher than desired.

Well, if Lockhart proceeds with granting Fannie and Freddie the ability to do rate/term refi’s with no appraisal required, then we will have our cake and get to eat it too — one might even think that such harmonizing actions were even planned…!

“The Committee is also evaluating the potential benefits of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities…”

Isn’t that another way of saying: “We will print more dollars?”

Hmmmm. Methinks inflation and dollar devaluation will be back soon in a very, very bad way.

Hi James,

Help me understand something – by lowering the rates to nearly zero, is the administration essentially doing nothing at this point?

The bank to bank lending rate is basically at zero, so dropping the main interest rate really does what? Banks are not lending to each other, how will this help?

Also, does lowering create a situation for stagflation – not inflation?

Best,

Van

The “clarification” about quantitative easing by the senior Fed official is somewhat unfortunate. It seems they want to fight a lost battle (although who knows what credit spreads would have been without the alphabet soup of lending facilities).

At the same time, the Fed has done well to move the target rate down so quickly (much, much faster than Japan in the 1990s and faster than other central banks currently), thus advancing the discussion about future policy along to where it needs to go in any event. However, the Fed should be clear as possible to the public about exactly what they intend to do in terms of “quantitative easing” and what their exit strategy is when there is an inevitable return of inflation.

I note in the language about potential benefits of purchasing longer-term Treasury securities an implicit allowance for the purchase of inflation-indexed bonds. By financing current government purchases with printed money in exchange for inflation-indexed bonds, the Treasury would be committing itself to supporting the Fed in the goal of low inflation in the long run.

Specifically, as assets on the Fed’s balance sheet, indexed-bonds would retain their value in the event of inflation, providing the Fed with liquid assets that it can sell to remove the excess cash and reserves from the economy (and thereby raising interest rates quickly and dramatically in the face of inflation).

I think there is a political economy angle here too. If there are a large number of inflation-indexed bonds out in the financial system, I think Congress et al. will be more supportive of Fed policy to reign in inflation than otherwise when the time comes. If current expenditures are financed with purely nominal bonds, I can only imagine that there will be immense political pressure on the Fed to inflate away the liabilities.

So what’s in it for Treasury (beyond possibly reluctant support for the principle of low inflation)? Presumably, the Fed could purchase newly-issued inflation-indexed bonds from Treasury at particularly good rates, although we might be talking about negative nominal interest rates in order to outdo what the market is allowing the Treasury to pay now.

The point is that this proposal of “quantitative easing” in terms of purchasing newly-issued inflation-indexed bonds makes it very transparent the extent to which “quantitative easing” would be providing finance for current expenditures, while also providing a credible commitment that additional financing of current expenditures won’t be provided by future surprise inflation.

I’m sure there is a flaw in this proposal, but it strikes me as safer than printing money to buy long-term nominal bonds. But would Treasury go for it?

i think if this fails, the only way left to kick start the economy will be for the fed to guarantee all future public and private debts.

they’ve done alot to bring down the cost of borrowing but havent done anything to address the credit risk component of lending yet.

The end of Plan A? That’s all? By my count, this is the end of plans C,D, and E. Now we are on to plan F, as in “we are totally F’d!”

Here is the cold hard truth!

Our government is not doing it’s job and while the approval ratings of the executive and legislative branches may seem low, the ratings are still much to high.

Fixing this credit crises.

This credit crises was ultimately triggered by consumers defaulting on their debt, especially mortgage loans, causing a cascade of defaults on many types of debts throughout this economy and spreading around the world. But this credit crises is feeding on itself because the unavailability of credit to the consumer is strangulating economic growth causing an increase in unemployment followed by a decrease in overall wages. This will ultimately cause even more unpaid consumer debt and cause an environment of even tighter credit conditions and continue to put even more of a strangle hold on economic growth and ultimately the inability to pay off even more debt – not to mention the strangulation of the future tax burden congress has put lately on the consumer. Increase taxes on the consumer alone is deeply deflationary.

In other words, the worst this economy gets the more of unpaid consumer debt there will be accumulated which will beget tighter and tighter credit.

The Fed believed that increasing liquidity to banks would spur economic activity by encouraging banks to lend money to the consumer, but the consumer, as a whole, is already in debt and is accumulating even more debt (because of interest owed on that debt) due to this deflationary environment. Banks are not going to lend money to a consumer already in debt and has no credit. Then comes a sharp decline in economic activity and decreased economic output followed by decreased overall employment and wages. This negative feedback loop has got to be broken.

As long as the demand for dollars continues to increase, its value will increase and banks and everybody else will hold onto them. Cash is king. The solution in to flood the economy with money by funneling it directly to the consumer so they will go out and spend it. The consumer needs to start paying off its debt first. So its going to take a huge amount of money and the longer it takes this government to identify this solution to fix the problem, the higher the unemployment rate will be and the more it will cost.

The Fed is not accustomed to fighting deflation. Deflation is a situation in which demand and prices of goods and services fall while the demand for cash rises. Consumers then have an incentive to delay purchases and consumption until prices fall even further, which in turn reduces overall economic activity – contributing to the deflationary spiral.

This current deflationary spiral is accompanied by an environment where the consumer can not obtain credit no matter how low prices go. Prices are going to decrease to the point where only the lucky people who still have a job will only be able to buy with cash. In the meantime, this economy will continue to contract into a vacuum bringing with it the consumer and businesses who had excellent credit only a year ago.

How do we break this cycle?

This cycle has to be broken while preserving the free market.

So, it needs to be broken with as little government intervention and bureaucracy as possible.

Our government knew earlier this year the most profound way to stimulate this economy was in the form of tax rebate checks and wasted no time passing the bill, but the amount was hardly enough. What the tax payer did with the money was either pay off debt or save it, which is precisely what needs to be done FIRST to save this economy. The magnitude of this problem was grossly underestimated, and the tax rebate was exactly the medicine this economy needed. So what else can possibly be done to boost confidence, consumer spending and economic activity that would be more effective than returning money directly into the tax payers/consumers hands? Nothing.

The consumer needs a larger tax rebate. How about $250 billion every quarter until this economy climbs out of this disastrous black hole? The deflationary spiral is going to spin out of control if the consumer is not saved. Ultimately, I doubt it would cost more than $1 trillion compared to the $3 trillion already spent bailing out financial institutions which has not only not yet loosened credit conditions but also has increased the future tax burden of America. $1 trillion returned to the consumer would average over $3250 for every man, woman and child. The government would easily get that tax money back from the consumer because of the surge in economic output that would soon follow.

When consumer debt begins to be paid back money will begin to circulate into the banks. This would free capital for banks to start lending. The important point here is that debt gets paid,and banks regain confidence to start lending again to a consumer no longer in debt.. The government almost has it right except that direct infusion of money to the banks does not pay off debt. Re-capitalizing banks will give them cash to lend, but not to a consumer already in debt , stressed for cash and has NO CREDIT.

The big picture here is consumer spending is the ultimate driver of this economy – not government spending. The eventual solution out of this mess will be less wasteful spending by our government and more tax breaks to the consumer and the private sector .Checks in the form of tax rebates are very stimulating but they are not only ever enough but also the government ends up taking it right back in the form of taxes. The bottom line is that this government takes too much of our money and waste it. Our government sure knows how to collect revenues through taxation, but does not know how to allocate its resources.

Do you think we pay all these taxes to pay for entitlements or we have all these entitlements because we have been paying too many taxes?

The government can not save every consumer. But as a whole the consumer has to get its head above water.

Think of the invisible hand of consumer sovereignty. The consumer will guide this economy out of this recession with a little capital and some tax relief.

Who else deserves tax payer funds more than the tax payer? Money spent by the consumer would increase aggregate demand for all goods and services thereby stimulating economic growth which in turn will increase the demand for labor and capital spending.

Im afraid that when all this dust settles congress is going to have finally realized that its train has run off its track and its the tax payer that needs the biggest bail-out of them all.

Reckless government spending is driving a stake through the very heart of the driving force of economic growth-consumer spending.

Imagine this statement coming out in a news bulletin:

Henry Paulson states, Today the Treasury Department decided the best and most quickest way to put the United States economy on the road to recovery would be not to risk tax payer funds on credit risk companies but to return tax money directly to the tax payers hands. We will let the consumer spend their tax money on goods and services as they please. If the consumer does not buy the goods and services you produce then so be it. Let the free markets reign.

Boy, would that be a surprise to the markets around the world.

Are you starting to pick up what I am putting down here? That 800 pound gorilla, that has been largely ignored in the room, is not Bear Strearns, Lehman Bros.,or GMC it is the consumer.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=99Dzdc1H0wM

For those having trouble following the logic of the arguments of the FED, Treasury and congress here is a video that should help make it clear. I found the econometics to be very helpful. 🙂

@Dr. D : of course its planned. do you think the guys in power are stupid ? look at the people Obama is shifting in place.

@DickF : great comment, :-).

—

People are like sheep.

What percentage of the 10% annualized 3 month deflation rate is caused by falling energy prices? If you remove the H1 runup and H2 retracement in energy prices, you still come up with a yoy rate above 2%, and still above the Fed’s preferred range. The current 3 month annualized core is in the 1-2% band it’s supposed to be in – not exactly the definition of deflation, and food price inflation is remaining elevated. The financial sector is still very weak and requires continued Fed balance sheet expansion, but zirp and quantitative easing are going to have unintended consequences down the road. How is the Fed going to normalize interest rates when deflation again turns out to be a hoax, but they’ve loaded the balance sheet of financial institutions with 4.5% 30 year mortgages, and encouraged them not to hedge and recapitalize via zirp?

Just more fuel on the fire…

I realize many commentators use the term “printing money” to describe actions currently being taken by the Federal Reserve, but I wonder if that phraseology is doing a disservice to comprehending what is actually taking place. As for currency, the supply of Federal Reserve notes is not being increased much, for the change in this liability on the Fed’s balance sheet over the past year is just 5%.

Instead, the Federal Reserve appears to be dipping into the cash reserves depository banks are required to maintain at the Fed and doing so for the purpose of lending cash or buying securities. It seems that, once these reserves are appropriated, they become liabilities on the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. Thus, as loan or security assets increase on the Fed’s balance sheet, so do liabilities to the reserves. Proof? The liability “Deposits – Depository Institutions” grew from $21 billion on 11/21/2007 to $630 billion on 11/19/2008, an increase of $601 billion. (Source: Federal Reserve’s H.4.1 report).

Can someone please verify that depository bank reserves maintained at the Fed are not reported as liablities on the Fed’s balance sheet until they are appropriated for use by the Fed?

Thank you.

While standard finance models treat spreads as a function of default risk, it appears that something else besides default risk is driving high yield spreads. Credit Suisse in recent work argues that non investment grade bonds are building in 65% cumulative default rates (assuming a 2% liquidity premium) which compares to the 35% rate we experienced in 1935. The conclude that this is a 1 in 50 year opportunity for low grade bonds.

To the extent that high spreads are due to panic, it seems that the Fed must try to do something to close yield gaps. Whether they will be able to do this or not is an open question.

As always, a great post.

Turbo: BLS reports that inflation in the core CPI (excluding food and energy) over the last 3 months corresponds to a 0.4% annual rate, not the 1-2% rate you say it should be in. I say 0.4% is not what we want at the moment.

Professor Hamilton, I agree with your view that we have to work toward reducing bank demand for reserves, and agree that your proposal is a good start. But I also wonder whether we are overlooking just how counterproductive the interest payments on reserves have been. Instead of focusing on how these interest payments have artificially held up the market fed funds rate, I would emphasize the impact they have had on bank hoarding of reserves. Yes, the new 1/4 rate is better than 1%, but why not negative 1/4–i.e. charge banks a quarter point for holding excess reserves? With the safe T-bill rate unable to fall below zero, presumably bank hoarding of reserves would decrease sharply. Then quantitative easing would work through the “currency held by the public” portion of the base. Because FDIC-insured deposits are now safe, the public doesn’t seem to be hoarding cash in the way they did during the 1930s. Thus more base money forced into circulation should boost AD through the old monetarist “excess cash balance” mechanism, as cash velocity would be very unlikely to decline as fast as the banks would disgorge reserves.

This idea is actually implicit in an inflation targeting plan proposed by Robert Hall back in 1983–I just dusted it off. Any thoughts?

Scott

JDH wrote:

BLS reports that inflation in the core CPI (excluding food and energy) over the last 3 months corresponds to a 0.4% annual rate, not the 1-2% rate you say it should be in. I say 0.4% is not what we want at the moment.

The fact that price increases are small is not a problem. This is the natural results of lack of demand. Pumping in liquidity will have no effect nor will the decrease in the FFR. Not until people are producing again will things change. If you child is crying because he wants breakfast you will not solve his problem by burying him under dollar bills.

I need to follow up my comment. Through much of what is considered the most prosperous period in US history at the end of the 19th Century prices were actually declining as the industrialists improved production methods and increased the supply of goods at a better quality. Our obsession with some level of price increases is a new phenomenon and reflects bad economics rather than some intrinsic problem.

Deflation is bad. Price decreases without deflation are a sign of prosperity amidst monetary stability.

JDH, it seems to me that the distinction the Fed is trying to draw between what it’s doing and quantitative easing is a distinction without a difference. When the Fed trades cash for dicey securities, doesn’t it create excess reserves, from which the banks can choose to lend? In effect, it’s pulling where Japan was pushing, but it imparts the same force and directionality.

Creating inflationary fears seems to be causing the dollar to dive, but the net upshot of that may well be that other countries feel forced to engage in quantitative easing of their own. That could make inflation very real… and difficult to control.

I think that the fiscal side is the one that will actually move things.

bert says: Banks are not going to lend money to a consumer already in debt and has no credit. Then comes a sharp decline in economic activity and decreased economic output followed by decreased overall employment and wages. This negative feedback loop has got to be broken.

The negative feedback loop will be broken when the price of housing comes down to the income level earned by the 85% of the labor force that is still employed.

Education, hospitals, government, personal service to elderly will continue to employ people. Retired folks have an amazing amount of purchasing power due to Social Security and the remaining 50% value of investments.

Van Santos: I agree with you that lowering the target accomplished essentially nothing.

Scott Sumner: Yes, I believe that paying interest on excess reserves was a bad idea.

Charles: My difference with the Fed is that I don’t think we wanted to encourage this ballooning of excess reserves at all– far better to try to get banks lending money. I also want the Fed to get that money into circulation by buying assets that it will make sense to sell back if the tide shifts too quickly, for example, if there is a rapid slide of the exchange rate, rather than trying to buy the assets that nobody else wants. The Fed should be buying TIPS and short-term foreign government securities, not MBS.

My more fundamental disagreement with the Fed is over what the primary objective is. The Fed thinks the objective should be to narrow spreads. I think the objective should be to generate some inflation.

Jim,

How much of that -1.7% CPI drop was due to falling oil prices? With the just-announced OPEC production cuts, we are probably seeing the end of those and possibly some increases again.

@ bert:

I recently used my stimulus check from the Treasury to purchase an inexpensive, all electric, high performance vehicle (I have no debt, only savings) which requires virtually no maintenance, smokes Porsche 911 Turbos and some Kawasaki Ninjas off the line, and has already increased in value 34.8% for a three month potential return on investment about 1,920 times greater than if I had stuck the stimulus into my savings (get your own next year’s street model – I’m not selling mine). I’m sure you all noticed how much better the economy is now than if I had not done that. Just imagine how bad it would have been in a decade if we did not use this opportunity to move forward on the increased efficiency road.

Or do we still have a chance to do the wrong thing again, like we did after 1973 and 1979?

KipEsquire,

Brilliant. Your logic is impecable. JDH is right.

Inflation is the only ticket out of this mess – markets simply do not recognize it yet.

The bond bubble will burst…how soon?…can anyone say?

Barkley: Yes, the -1.7 was energy. But the month-to-month change in core CPI for November was 0.0. I say that’s too low given the current environment.

JDH – my mistake, I was looking at a trailing 6 month number, not the BLS 3 month annualized core. The 1-2% band is also the Fed’s informal band, not what I would recommend. I happen to agree the Fed should be creating some inflation to reflate bank balance sheets right now, but the key word is some. The financial system is stabilizing and the Fed may have done enough at 1% plus the alphabet soup of liquidity measures – monetary policy works with 6-9 month lags afterall. If you managed according to the June-Aug 3 month annualized core rate, then the Fed should have been reluctant to cut last fall (when it was clearly needed), but going to zirp with the promise of sub-3% long rates is probably overkill at this point – there’s a tremendous amount of monetary stimulus and credit repair measures in the pipeline that are only just now starting to work. The Fed has a long history of being slow on the uptake, then over-reacting. Sometimes to put out a forest fire you create a controlled burn. This feels like the Fed just panicked and napalmed their controlled burn.

Take a look at what the M1 money multiplier has been doing.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_nSTO-vZpSgc/ST7ujh4TtcI/AAAAAAAAD9M/uudLWS6Ss6k/s1600-h/M1-Mult.png

It looks like the monetary base has become M1.

I got the above graph from —

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com/2008/12/huge-demand-for-treasuries-as-banks.html

“But the month-to-month change in core CPI for November was 0.0. I say that’s too low given the current environment.”

Yes, but that is still not deflation. Only if we get -0.2 or greater could we say that we are getting significant deflation.

If you haven’t before now, it might be a good time to panic. It is pretty clear that either: 1) the Fed doesn’t know what it is doing or 2)knows exactly what they are doing because they are scared S_ _ _ _ _ _ . I am agnostic as to which might be true but it is very clear that the worst is NOT behind us.

“I am agnostic as to which might be true but it is very clear that the worst is NOT behind us. ”

It depends.

1) The worst is NOT behind us in terms of job loss. Another 2-4M jobs will be lost.

2) In the stock market, it is possible that the worst is behind us (but time will tell).

3) In housing, there is one more tick down that has to happen.

Prof Hamilton, you write “…But while the Fed may have little control over the spreads between different interest rates, it does have a significant degree of control over the inflation rate…”.

Now I know the just about everyone agrees that large changes in the quantity of money determine changes in inflation or deflation more than anything else. But mustn’t their be a **channels** (as Menzie Chinn has written here https://econbrowser.com/archives/2008/01/thinking_about_2.html) between the money supply and prices. After all, business and individuals bid and offer prices not by checking the Fed’s weekly balance sheet, but by looking at supply and demand in the particular markets thay participate in.

In a closed economy, don’t all of the channels relate either to the effect of interest rates on demand from investment or consumption, or, possibly, real wealth effects? And in an economy in some way open to world markets, aren’t changes in the exchange rate a principle channel? Am I missing any other channel?

Now if we a small county with a floating exchange rate, I can see how material changes in the money supply would materially change the exchange rate and pass through one-to-one, to prices of agriculatural goods, minerals, energy and imported manufactures, whose prices are set in markets outside the country, and denominated in foreign currencies.

But not only is the US economy large and relatively closed, it is also today on a partially-fixed exchange rate regime since China and the Gulf states more or less peg to the $. At this point, however much money the Fed prints, its not going to lower the $-Renminbi exchange rate ’cause China won’t allow it.

To a great degree this leaves the aggregate demand channels. And since “safe” interest rates are already more or less at zero, that leaves us to the question as to whether huge changes to the monetary base, in and of themselves have real wealth effects

Regardless, I don’t see, at this point in time, how changes in the **dollar** money supply, in and of itself, affects, in any reasonable period of time, the US price level, except by increasing demand, and thus output, either in the US or elsewhere in the world.

Back in March (at Economist’s View) I suggested that the US Govt. might get the best result in terms of protecting the “real economy” not by bailing out banks or other bankrupt companies but by creating a new bank itself. I suggested (just to fix the idea in people’s minds) calling it The Commonwealth Bank of the United States. Such a Govt.-owned bank could operate on its own once capitalised by the US Govt., with a mandate to pay a reasonable rate of return to the taxpayer and otherwise to act as a commercial bank. Rather than bailouts, Govt. money could then be directed to creditworthy borrowers in the real economy. After all, the aim of Govt. intervention is to prevent a financial crisis from disrupting the real economy, not to reassemble an unstable and unwanted financial house of cards. Isn’t it?

Try this on for size: when banks get an interest rate deal, like after 9-11, they can accept loans at the lower rate in return for given up some balance sheet transparency for the loans in question. If I’m a central banker seeking stimulus, instead of creating a bubble for tommorrow’s central bank and tomorrows taxpayers and the kiddies, I offer the option for stimulus at a lower rate in return for making the borrowing details completely public.

Say the fed funds rate is 2%, and I want more interbank loans or more industrial payroll loans or whatever. If I’m the CB, I keep the rate at 2%, and offer a 1% financial-trade-secret-tattle loan rate for anyone who doesn’t mind making some coarse details of the contract public. It doesn’t help now, but if this were done in 2001 instead of no strings attached cheap interest rates, I’m guessing people taking massive financial positions based on sub-prime mortgage collateral would consider a housing bubble and second guess Moody’s.

I also think both Republican and Democrats, and maybe even Greens and Libertopians should be given a sliver of public dollars to each establish credit rating agencies to compete with Moody’s. A mosiac of conflict-of-interests if you will.

Gordon, I came to the same conclusion recently. You could have the shadow banks already to go well before a crisis and you could privatise them to the highest bidder whenever conditions improve. At some level of leveraging/derivatives (if extreme knife-edge types of contracts are deemed necessary for some reason) it might be best to keep the bank public and transparent.

gelboak: The money is created by the government purchasing either assets or goods, the latter in practice in the form of the Treasury issuing debt to buy goods and the Fed buying the debt with money. If you maintained that the prices of both assets and goods were completely unresponsive regardless of the magnitude of these purchases, you are postulating the power for the government to create infinite real wealth for itself and the taxpayers. The view implies we could completely retire interest-bearing government debt, appropriate all the world’s wealth on behalf of U.S. citizens, and build an infinite quantity of bridges or any other darn thing the government might care to have, paying for it all with costlessly created money. I find that view incomprehensible.

The channel is that if there were an increase in the money supply with no change in the price of any asset or good, there would be an excess demand for assets or goods.

Sound politics. The Feds introduction of the payment of interest on excess & required reserves proved more difficult than expected.

The Feds technical staff cant quantify / calculate the correct remuneration rate on excess reserves.

With the Fed issuing its own debt, its balance sheet expansion (lending/discount operations) could be mopped up on a dollar for dollar basis.

However, the Fed cannot offset these advances on a very large scale – without destroying the Treasurys capacity to manage the national debt.

Prof Hamilton, thank you for the response, at 5:06am!

JDH:“…If you maintained that the prices of both assets and goods were completely unresponsive regardless of the magnitude of these purchases”

Semanatic confusion here. I did not mean to leave the impression that the prices of **both** assets and goods are completely unresponsive to central bank actions. When you wrote of FED control over inflation, I was taking that to mean inflation the way it usually measured – inflation in goods and services as shown in things like the CPI, PPI, GDP deflator, etc. I do not define inflation in terms the prices of bonds, land, stock,or other assets (after all, when US housing prices skyrocketed between between 2001 and 2006, or when stock prices inflated during the dot-com bubble, people might have talked about “inflation in housing values” or “asset inflation”, but not “inflation”.

As for the ability of the FED to influence asset prices, I think we need to think in terms of a continuum between “pure monetary” measures and the more creative things it has been doing, which you have previously written should be purview of the Congress as the fiscal authority

Take the first extreme. As of 11/30/2008, there was $2 trillion of T-bills outstanding held by the public. Suppose the FED bought all of that (30% of the publicly held debt!) tomorrow? T-Bills are already trading at face value, so the market today considers them near perfect substitutes for US currency/depository reserve balances. Would such an action change the price of anything?

Now if the FED bought started buying lots more treasury bonds and 5-10 year notes, the prices of those instruments would go up (though I still would not call that “inflation”). If they tried to buy all $3.8 Trillion in notes and bonds held by the public, its anyone’s guess what would happen. It would certainly lead private market participants to put downward pressure on the dollar. But at this point the worlds’ major central banks seem to be locked in cycle of competitive monetary loosening, since no major economic block outside the US wants to see its currency appreciate too much. Even greater quantitative easing by the FED will as a matter of policy be matched by the Peoples’ Bank of China, and would most probably be matched by the ECB and by Japan. It *might* be that a large enough money printing move would be perceived as *such* a long run inflationary risk that it would cause a catastrophic run on the dollar, with the worlds central banks joining in on the the panic. No doubt this latter scenario would be inflationary for the US in every sense of the word, but I would describe it as psychology-driven rather than as a direct consequence of the FEDs purchases. However your would describe it, it would still fall under my “exchange rate channel” category. Implicit in my argument is the observation that given the policies of the other central banks, not to mention considerations of US foreign policy, the FED does not have the ability to create a controlled, measured and orderly short term depreciation in the dollar exchange rate with the Euro, Yen, Renminbi, etc.

JDH: The view implies we could completely retire interest-bearing government debt, appropriate all the world’s wealth on behalf of U.S. citizens, and build an infinite quantity of bridges or any other darn thing the government might care to have, paying for it all with costlessly created money.

Multiple thought experiments here.

By “appropriate the worlds’ wealth” I assume you are thinking of scenarios where the FED creates money to buy **risky** assets (US and foreign equities, land, formerly AIG and Bear Stearns-owned CDOs, junk bonds, etc.) My answer to this would be the same as yours. If, ex post, it turns out that that printing-press happy FED overpayed for these risky assets, then it would ultimately realize a capital loss, which would reduce fututre remittances of FED profits to the US Treasury, at the expense of the US taxpayer. If the FED underpayed for the risky assets, then the taxpayers of the future profit from teh capital gains, while the private current holders of the risky assets who sold forgo the future capital gain (that they don’t know about today). In either case, the lack of a free lunch is not because such purchases are inflationary, but because in any bet one side wins and the other side looses.

JDH: …build an infinite quantity of bridges or any other darn thing the government might care to have

OK, now we are talking about monetized *fiscal* stimulus. I agree that a large enough deficit spending would eventually be inflationary, but it would be so through the aggregate demand channel. As long as there was significant unemployment and real policy interest rates stay at zero, the first impact of FED-funded govt spending would be to increase output. Only as real short term safe interest rates rise above zero and unemployment goes below recessionary levels would such expenditures begin to bid up prices of produced (non-asset) goods and services

It amazes me how most economist want to print more funny money to get out of a problem that was created by printing funny money. Deflation is a decrease in the money supply resulting in decreased prices, hopefully wages and assets. As long as full employment is maintained no real value has been lost. It doesn’t matter how many zeros’ you put on the funny money. A house is still a house.

This deflation should be allowed to proceed until the current over valued asset,homes, is easily affordable at market rates, not artificle government rates, by wages. Employment could be regained by eliminating 10% of government and eliminating the corporate and cap gains tax in favor of a flat tax on all income or a consumption tax. Good luck with a monetarist at the Fed and a keynesian/marxian in the white house