I was sitting in a briefing recently, where I heard how US GDP would be measurably affected by the floods in Thailand –- specifically through the shutdown of production of key auto parts. [0] That reminded me of the supply-chain-propagated impact of events nine months earlier, following the earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Here’s the trade-related part of the assessment from my colleague Isao Kamata’s article in the La Follette Policy Report, “The Great East Japan Earthquake: A View on Its Implication for Japan’s Economy”:

…

Impacts of Disruption

of Supply ChainsThe Tohoku and northern Kanto regions severely damaged by the Great East Japan Earthquake had been populated by many firms that produce materials

(such as metals and chemicals) and parts of motor vehicles and electronics. The disaster damaged these firms and stopped their production activities; it also stopped or diminished the production activities of non-disaster-affected firms that used the products of the disaster-damaged firms, because of the shortage of those intermediate inputs. This phenomenon of disrupted supply chains amplified the impacts of the disaster on manufacturing production and expanded the impacts broadly to other (non-damaged) regions in the country.

The impacts of the disruption of supply chains have been the largest in the transportation equipment industry that includes manufacturing cars, trucks and their parts. According to statistics from Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), the total manufacturing production in March 2011 was 15.5 percent lower than that in the previous month, which was the largest decrease for 58 years since the production index was established. More than a half of this decrease was due to a drop in production in the transportation equipment industry, which experienced a 46.7 percent decline in March 2011, the disaster month. The industry further decreased production by 1.9 percent in April, while the total manufacturing production recovered by 1.6 percent in the same month. This large impact on nationwide manufacturing production should indicate the complexity of today’s supply chains that have been globally constructed for production efficiency and cost minimization. It may also be that intermediate products supplied by the disaster-damaged firms had been so specialized that the “downstream” producers cannot readily switch to alternative products or suppliers. The large nationwide decrease in manufacturing production in March likely is not solely due to the disrupted supply chains but also to the rolling electricity blackouts prompted by the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Rolling blackouts were not implemented in April.

An initial fear was that the impact could become more severe if the disruption of the supply chains continued. If “downstream” producers, such as a General Motors truck plant in Louisiana, anticipated that the shutdown or partial operation of the disaster-damaged firms, they might seek material from other firms to maintain production. With the global nature of supply chains, those alternative suppliers could be in other countries. One concern is that if new supply chains are established, Japanese firms damaged by the earthquake and tsunami might find they are excluded from the market when they are able to restart manufacturing of intermediate products. This scenario could permanently lower Japan’s manufacturing production and exports.

However, the operation of the disaster-damaged Japanese firms and the supply chains recovered very rapidly, due to large efforts of those firms themselves as well as related “downstream” producers to recover. A METI survey shows that, as of early April, more than 60 percent of the damaged firms have been restored, and another 30 percent were expected to be restored by summer 2011. Their actual restoration seems to have been even faster.

…

I had wondered whether this event would spur a reversal of the development of supply chains. [1] It’s too early for a quantitative assessment, but clearly managers are thinking hard about this issue, particularly in regard to China. From FM Global Supply Chain Risk Study: China and Natural Disasters – A Case for Business Resilience:

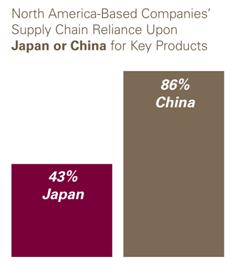

Nearly nine in 10 companies surveyed (86 percent) are more reliant on China as part of their supply chain for their key product lines than they are on Japan (43 percent).

Figure 1 illustrates the differential response.

Figure 1 from FM Global Supply Chain Risk Study: China and Natural Disasters — A Case for Business Resilience

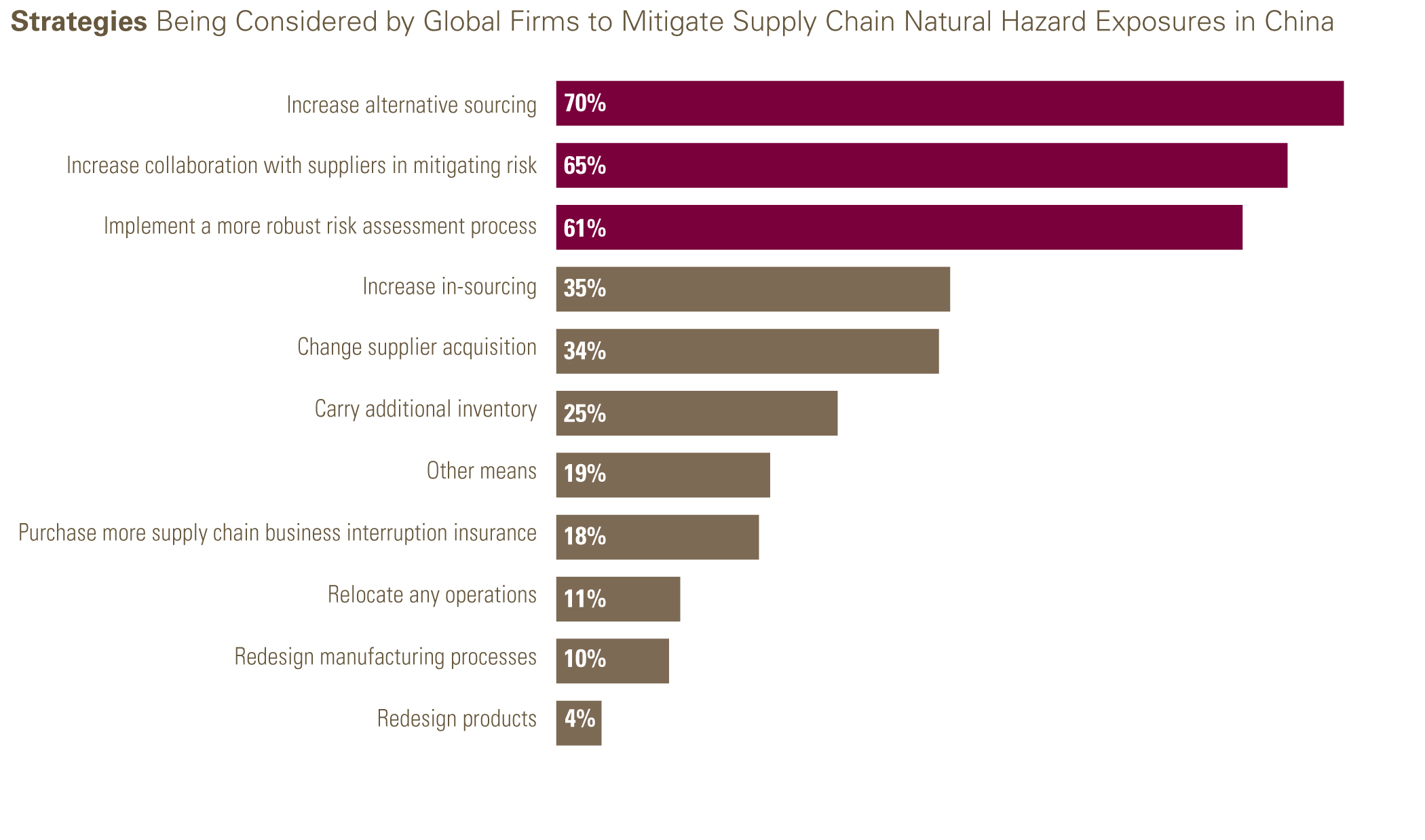

There are a variety of ways to respond to such a risk. One way is to make sure there are multiple suppliers. Another way is to increase in-sourcing; this is what I speculated might happen as risks of disruptions abroad increased, and transportation costs remained elevated [2] [3]. Figure 5 illustrates how the surveyed firms are considering responses to these perceived risks.

Figure 5 from FM Global Supply Chain Risk Study: China and Natural Disasters — A Case for Business Resilience

To me, it looks like relocating production back to the US is pretty far down the list (4th). Given the difference in labor costs, one can think of this as either unsurprising, or surprisingly high.

More on supply chains here. Professor Kamata’s article deals with additional economic aspects of the disaster.

The topic of offshoring/outsourcing will be covered in Professor Kamata’s Public Affairs 856 course, taught this Spring at UW Madison. (Spring 2011 syllabus.) And on this coming Tuesday at 3:45, Jon Vogel (Columbia University) is presenting “An Elementary Theory of Global Supply Chains” with Arnaud Costinot and Su Wang, in the International Workshop at UW.

and them yahoos in congress are threatening iran, who china has vowed to defend? yikes!

Too much emphasis nowadays is placed on economic convenience, without factoring in those darn externalities – which always pop up in the most inconvenient moment, tsk tsk…

What if we started to focus on some sort of “real price” which accurately reflects the ” premium value” of availability of supplies?

I think we all remember what happened in 2010 when several EU airports ran out of antifreeze and closed – because nobody was stocking enough and the supply chain was disrupted by an exceptional snowstorm.

Or during the SARS epidemic… from firsthand I know operators in the textile business who did not want to receive any goods from China – let alone conduct their in-person business down there.

So I think that the next bottleneck / disruption will always be around the corner – unless we take steps to… hmmm… create production capacity close at home. Hint, hint.

A practical and thorough study from Nobuaki Hamaguchi “Regional Productive Integration in East Asia” ,commissioned 3 years ago it may not have changed much in content, since industries migrations towards Asia outsourcing have been a reinforcing trend through this decade.

The industrial belt in Asia is located near the sea harbors,with good infrastructures and roads access to the production centers.

A large Asia intra trade of semi finished products and intermediary goods where the finished products are exported to the consumers countries Europe,USA.

It would be interesting to revisit the flows and products content within the triangle Japan,Taiwan,Korea (P23) when knowing that China more integrated industries may have outpaced the direct trade flows with the consumers nations.

Hmmm… eggs in one basket… old adage….

It’s not just long supply chains. It’s “Just-in-time” inventory management as well.

Back in the dark ages, when I was an undergrad, JIT was just coming into being, and one of my profs was a retired guy from industry. He said that he was not personally comfortable with the incredibly low levels of inventory required by JIT, and could recall many times in his long career that having a few weeks supply of a part on the shelf bailed him out. I am sure that he was thinking more about strikes at suppliers rather than earthquakes, but the principle is the same.

With interest rates being so low, isn’t it actually less costly than in the past to hold inventory? What is the return to JIT vs. the risk?

I think this is a fairly complicated and often quite company-specific topic.

For example, companies will tend to outsource where they also have sales. That’s both economically and political prudent in many cases. Production and other functions may specialize: more assembly in China, more customer support in India, more design and engineering in California.

Companies are prone to management fashion as well. Think local, act local. Think global, act local. Think global, act global. All of these come and go in fashion.

I do think sophisticated companies try to take into account political risk. But it’s hard to do. I was working on a capital raising for an Italian-Canadian-Thai firm in Bangkok during the Red Shirt demostrations last year. Protestors riding in motor bikes and pick-up trucks didn’t help the effort then, but everything seems back to normal now. At some point, company management has to put their money into some jurisdication. They hope to get the call right more often than not. But it’s very hard to anticipate political risk over a longer horizon.

Buzzcut

Far from any expertise on my part, I have the following questions.

Are interest rates the largest concern for holding inventory at higher levels? I seem to remember that that tax consideration are also large. Am I right that at years end, inventory on hand directly go to bottom line taxation?

General comments. I am impressed by the rapidity that parts manufacturers return to production after such extreme disaster. I would have expected time in years not months. Rigor of private enterprise is truly impressive.

Call me a cynic, but the justification for outsourcing is generally to help executives meet financial targets. Any mitigation of the risks, such as holding more inventory or having multiple suppliers, is going to cost more money in the short-run; so it won’t be done.

No matter where you outsource work you cannot avoid the biggest risk of outsourcing, losing control of the work. Suppliers do what’s in their interest, even if that means shipping substandard product or not meeting your production schedule.

I thought tsunamis and broken windows and all that jazz was supposed to help the economy?

Silas Barta: Only because you have been reading caricatures of economics by poorly trained economists.

Alright, I’ll stop reading Krugman.

Silas Barta: I would welcome seeing the article where Paul Krugman asserts that the effects of tsunamis and earthquakes are welfare-enhancing. Please provide URL at your earliest convenience, for all Econbrowser readers to see. Thank you, in advance.

Menzie, I think you got him there.

I said “help the economy”, not “is welfare enhancing”, and it’s not my fault the mainstream has for so long blurred the distinction.

Another oil comment:

The model we use assumes that oil consumption is price inelastic. Thus, increasing oil and gasoline prices do not lead to reduced oil consumption in the short run. Rather, households reduce savings, increase debt or reduce consumption of other goods. They are believed to be willing to do this because oil is an “enabling commodity”, a catalyst that enables other activities and thus is worth more than the value of the commodity itself. For example, if you can’t drive to work, you can’t earn a paycheck either, and therefore are willing to pay more for oil to protect a stream of income.

In the last year, however, oil demand does actually look reasonably elastic to me. Our model forecasts that US oil consumption should fall 1.5% per annum on average. In the last year, it fell by 1.3%–which is pretty close. Thus, in the recovery from the recession, oil demand would appear more elastic than we might expect. Could this be just an anomaly of the data? We’ll have to see. But a continued fall in oil consumption without triggering a recession would suggest greater price elasticity of demand than we saw before the recession.

Silas Barta: But you implied that Paul Krugman was one who had blurred this distinction by providing a specific name — so I once again request the specific reference/URL that substantiates your claim.

Re: comment on Oil consumption. The issue is the time constant of the elasticity. In the long term oil demand is elastic, as autos are retired and new ones introduced if the price of oil goes up then they become more efficient. However it takes a price above a limit to trigger this. Also in general higher energy prices have effects on the replacement of other items for example home hvac systems which tend to be the big consumers in homes in most of the US. Consider that a 30 year old furnace for example may be 50 to 60% efficient, where as todays furnaces start at 80% and go above 90% as you spend more. Thus you can reduce home demand when you replace.

Are interest rates the largest concern for holding inventory at higher levels? I seem to remember that that tax consideration are also large. Am I right that at years end, inventory on hand directly go to bottom line taxation?

I don’t know. I know that my state used to have an inventory tax, but that was eliminated a few years ago.

There are probably accounting considerations that are more important than interest rates. How quickly you turn over inventory is often an easily calculated and much watched metric. You know, MBA stuff. 😉

@Menzie_Chinn: Waaaait a sec now. You just interpreted my reference to “better economy” to mean “welfare-improving”, and now you’re trying to challenge the claim that the mainstream hastily equivocates between the two?

Um, Exhibit A: Find a good mirror, and gaze into it.