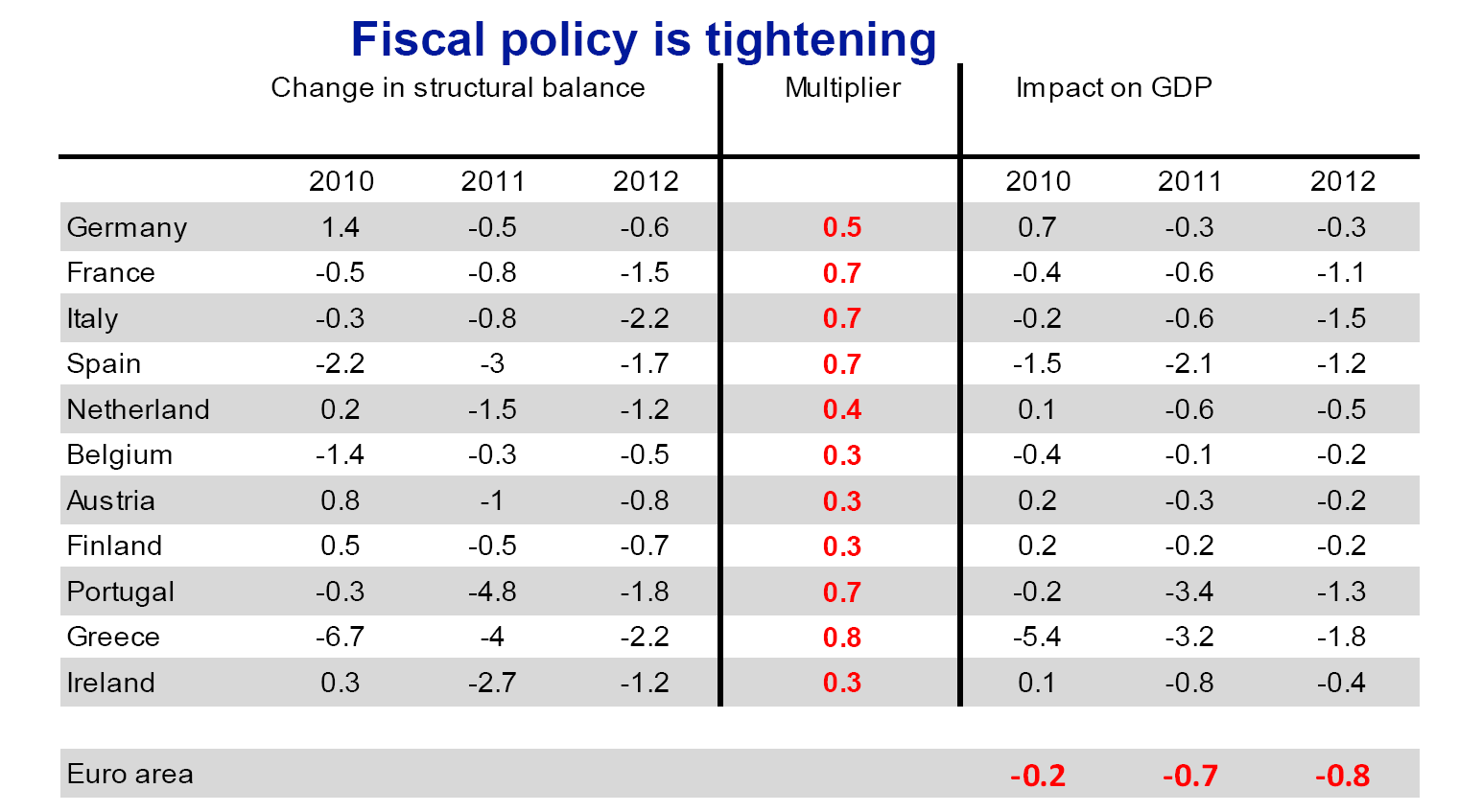

From Deutsche Bank, “Fighting the Clock,” Fixed Income (May 2012) [not online], some estimates of changes in structural balances, multipliers, and output impacts:

Note: a negative sign under “change in structural balance” indicates an increase in the surplus.

Note that these are multipliers for composites of transfers, taxes, and spending on goods and services. Multipliers for pure spending on goods and services (government consumption) would be larger. (Just an observation — these are not guesses from ivory-tower bound academics, but from business sector economists.)

A recent IMF working paper by Corsetti, Meier and Mueller notes:

This paper studies how the effects of government spending vary with the economic

environment. Using a panel of OECD countries, we identify fiscal shocks as residuals

from an estimated spending rule and trace their macroeconomic impact under different

conditions regarding the exchange rate regime, public indebtedness, and health of the

financial system. The unconditional responses to a positive spending shock broadly

confirm earlier findings. However, conditional responses differ systematically across

exchange rate regimes, as real appreciation and external deficits occur mainly under

currency pegs. We also find output and consumption multipliers to be unusually high

during times of financial crisis.

The findings in this paper suggest that fiscal contraction will be particularly contractionary in the current-day eurozone. They also indicate that if policymakers come to their senses abandon the current approach of trying to stabilize via austerity, and instead aim for stimulus with back-loaded fiscal retrenchment, the ongoing recession could be mitigated.

The numbers are interesting; a pity the DB report isn’t online. Thinking in simple IS-LM terms, the story is incomplete without noting that ECB policy may be a bit loose for Germany and much too tight for the rest of us. And from an Irish point of view the governments’s fiscal stance is not nearly as big a worry as the lack of demand for exports. We could handle austerity at home if it wasn’t for austerity abroad.

At last we are out of Wisconsin! Hooray! With Government Walker re-elected and the mandatory period of moaning and sniveling in the faculty lounges over, we can get back to the world.

“instead aim for stimulus with back-loaded fiscal retrenchment, the ongoing recession could be mitigated” which, of course, never comes.

Are we not now seeing the “backloaded fiscal retrenchment”? Greece was running a big stimulus program of perhaps 15% of GDP prior to the recession. The EU and the IMF either didn’t know or didn’t want to know how big the true Greek deficit was. And Greek participation in the Euro Zone facilitated this borrowing spree by providing low interest rates. For Greece at least, this is a nasty and painful correction, but it’s unavoidable.

On the plus side, it looks like Spain and Greece took the worst of it in 2011 and should be back at par by 2013. For these countries, the end of the contraction is in sight, it I extrapolate DB’s figures.

It’s now the turn of France and Italy to pay the piper.

Bruce,

I agree with your point. The assumption is that the stimulus always works. However, firms will only begin hiring if they expect the stimulus to work. Right now, I don’t think there is a borrow and spend stimulus package that could convince firms to expand. Maybe a tax cut package would be more appealing, or there is always the inflate your debt away approach that Menzie supports.

I wonder what would happen if Greece announced they were borrowing XXX Billion euro and lowering taxes today, but offering to reduce the growth rate of spending and increase the growth rate of tax revenue in the future? I don’t think the debt market would view their promise as credible, and would punish Greece with higher borrowing rates and default in short order.

What is “back loaded fiscal retrenchment?” What is the difference between “fiscal retrenchment” and austerity? Why do we need a pig dressed like a king when plain English makes it much clearer?

Steven Kopits

Greece was running a big stimulus program of perhaps 15% of GDP prior to the recession.

No, this is simply wrong. Greece never had a stimulus program anywhere near 15% of GDP. Greece did have a deficit ~15% of GDP, but the level of the deficit is not synonomous with the magnitude of fiscal stimulus. Stimulus refers to the change in the deficit, not the level of the deficit.

On the plus side, it looks like Spain and Greece took the worst of it in 2011 and should be back at par by 2013. For these countries, the end of the contraction is in sight

I don’t see the evidence for this. Earlier this week the Greek government announced that GDP fell 6.5% in 2012Q1 relative to 2011Q1. The structural deficit in Greece might be “improving,” but the Greek economy overall is getting much worse.

tj

if Greece announced they were borrowing XXX Billion euro and lowering taxes today, but offering to reduce the growth rate of spending and increase the growth rate of tax revenue in the future?

It’s unclear if you’re aware of this or not, but the effective tax rate in Greece is and has been very low. That’s the main reason Greece got into fiscal trouble. The nominal tax rates in Greece were pretty high, but the government simply didn’t bother to collect taxes. Lowering the tax rate would only make things worse and increase Greece’s credit risk.

The assumption is that the stimulus always works.

No, that is not the assumption. The assumption is that sometimes aggregate demand falls below potential output and there are ways to close the output gap. Ideally, and in normal times the Fed should close the output gap. When the economy is at ZIRP and in a liquidity trap conventional monetary policy isn’t effective, but fiscal policy can be. There is no guarantee that fiscal stimulus will always work, but if fiscal stimulus doesn’t work you can be pretty sure that simply waiting around for the economy to self correct won’t work either. It is possible for the economy to get stuck in a bad equilibrium in a liquidity trap. For example:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w18114

Note the graph showing multiple equilibria.

However, firms will only begin hiring if they expect the stimulus to work. Right now, I don’t think there is a borrow and spend stimulus package that could convince firms to expand.

So firms are in the habit of leaving money on the table? If the government buys goods and services that creates demand. Are you saying that every firm will choose to let its competitors provide those goods and services? This is nutso-economix.

It is a theory, a pro cycle fiscal expenditures, when an economy is contracting and the reverse in expansion.

How many countries can exhibit this flexible record during this decade. The above axiom, translated in the micro world of business.

Increase borrowing for working capital but with few caveats, to support increasing administrative expenses, no negative pledge on assets, no pledge on assets either, no covenants on borrowings and balance sheets, no remedy on administrative expenses, no proper assessment of the accounts, no new products, maintenance of the status quo with violation of all previous undertakings. The staff is proved to be amoral and immoral but in compliance with the executive instructions, most of them have shown a good exit strategy for themselves. In short, credit the money on account and timely.

Looking at the ECB statistical warehouse (Please go to Government finance, expenditures then, Euro area 17 (fixed composition), then Gross fixed capital formation, data chart) the fiscal incomes are meeting with decreasing return. The investment in GFC formation has never been high in GDP percentage a median of 2.5% but ECB statistic pocket book shows that governments expenditures represent an average 50% of GDP.

General government expenditure

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/stapobo/spb201206en.pdf

In summary please explain where and when the fiscal expenditures are going to produce a beneficial return to the nations and an exit strategy on pending debts.

Slug wrote:

Greece never had a stimulus program anywhere near 15% of GDP. Greece did have a deficit ~15% of GDP, but the level of the deficit is not synonomous with the magnitude of fiscal stimulus. Stimulus refers to the change in the deficit, not the level of the deficit.

Slug,

This may be one of the most profound statements you have written in a long time.

The Austrian Business Cycle Theory (Hayek, Mises) states that the boom phase of the business cycle is caused by monetary stimulus that artificially “stimulates” the economy giving the illusion of growth through malinvestment. But quickly the illusory effect fades and additional “stimulus” is needed to maintain the illusion. As you state the only “stimulus” effect is through continual and increasing injections.

The injections whitewash the malinvestment for a time, but a point is reached when the malinvestment becomes greater than additional stimulus can hide and we experience the bust, the economy falls apart as deleveraging of the malinvestment begins.

At this point in the cycle no amount of stimulus will continue the illusion. It will flow into various sectors depending on fiscal conditions: bank reserves, or commodities, or collectables, or, as in the 1970s, inflation.

Your statement is a very succinct and clear explanation of this aspect of the ABCT. Thanks.

Slugs –

The Greeks were apparently borrowing something like 15% of GDP. On the way up, this was stimulus, but as you point out, the annual increment only.

As for Greek GDP, I can rely on the chart DB provided and Menzie presented. If that’s wrong, then it’s not such a great chart, and we can’t rely on the conclusions drawn therefrom.

Having said that, if my observation is correct, then Greece might remain in the Euro with another year or so of grinding and probably an additional bailout. But it is possible to bail out a country with a primary surplus. I would probably put myself in the DDD (depart, devalue, default) camp, but the numbers as presented by DB do suggest that remaining in the Euro might be technically feasible.

My primary concern, however, is not financial. It’s about governance. Will DDD improve Greek governance, or is a Euro Zone grind down the better way to go?

You know my feelings: When we are willing to pay politicians for the value they manage, goverance will improve. That’s my first choice, and could achieve good governance within or without the Euro Zone. However, if that’s not on the table, then it comes down to some murky judgments. Recall: It is membership in the Euro Zone which caused this financial crisis. It did so by allowing excessive borrowing at low interest rates. Thus, Euro Zone membership played a crtical role in facilitating bad governance. Will it be a more positive force in the future?

Slug wrote:

It’s unclear if you’re aware of this or not, but the effective tax rate in Greece is and has been very low. That’s the main reason Greece got into fiscal trouble. The nominal tax rates in Greece were pretty high, but the government simply didn’t bother to collect taxes.

Slug,

You just keep hitting home runs! Keep it up!

This is exactly what supply side theory teaches. when tax rates become too high there is both massive tax evasion and tax avoidance.

Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations Volume II, Book V, Chapter II, part II, put it this way.

Slug wrote:

There is no guarantee that fiscal stimulus will always work, but if fiscal stimulus doesn’t work you can be pretty sure that simply waiting around for the economy to self correct won’t work either. It is possible for the economy to get stuck in a bad equilibrium in a liquidity trap.

Right!Keynes does recognize that the illusion cannot continue indefinitely. Even though Keynes was ignorant of the teaching of the greatest economists of his time, Menger, Bohm-Bawerk, Wieser, Mises, and Hayek, he recognized that there was a point where monetary stimulus no longer supported the illusion. Keynes, as was his practice, coined a new term “liquidity crisis” to recognize the point where the illusion fell apart. Sadly, Keynes did not know that the grezt Austrian economists had already dealth with this and Keynes chose not to dig into the reason for the “liquidity crisis” but instead focused on attempts to get around it a perpetuate the illusion. I believe this was just another example of Keynes being so wedded to his “new” theory that he traded truth for rationalizaiton. His recognition of the “liquidity crisis” took away his most powerful tool, but he simply could not admit his error and abandon his celebrity.

Sadly, once the malinvestment is created and the “liquidity crisis” manifest economic decline is inevitable. In one sense your comment, “if fiscal stimulus doesn’t work you can be pretty sure that simply waiting around for the economy to self correct won’t work either” is absolutely true, the malinvestment must be worked off and so economic decline has been baked into the economy. But in another sense doing nothing does work as was proven in the recovery from the 1920-21 recession. Doing nothing allows the malinvestment to be reallocated to productive uses or culled from the economy.

Slug wrote:

So firms are in the habit of leaving money on the table? If the government buys goods and services that creates demand. Are you saying that every firm will choose to let its competitors provide those goods and services? This is nutso-economix.

Slug,

Here you drift back into Sudoku thinking. In a Sudoku sense when the government buys goods and services it creates demand, but there is no recognition of the efficiency of this demand. The government must take resources from the productive economy and by nature its purchases are less efficient and more costly (simply the act of creating a bureaucracy to confiscate the funds is additional cost). So actually, it is the government that is leaving money on the table, probably more accurately throwing it into the garbage because much of this additional cost is sunk cost. I do agree with your final assessment. It is “nutso-economix.”

Steve Kopits On the way up, this was stimulus

Only if the Greek economy was operating below its NAIRU and assuming the ECB did not frustrate the deficit spending. Increasing the deficit at the NAIRU full employment level does not stimulate economic activity, it just crowds out. It seems that many conservatives understand the concept of crowding out, but they just don’t understand when it is applicable and when it is not.

Ricardo This is exactly what supply side theory teaches. when tax rates become too high there is both massive tax evasion and tax avoidance.

Actually, I think that’s what James Mirrlees teaches in his work on optimal income taxation:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Mirrlees

Supply side economics argues that lower taxes induce a shift between income effects and substitution effects leading to increased economic effort as people choose more labor over leisure. That’s a slightly different argument.

Here you drift back into Sudoku thinking.

Forgive me. I was at a military operations research symposium all week and one of the more interesting unclassified presentations was an Air Force Academy developed Suduko heuristic model for targeting. Maybe some of it carried over. In any event, it’s hard to see how employing otherwise idle resources to fill even low priority public goods needs is somehow less efficient than allowing those resources to remain idle. Even a 0.01% rate of return is greater than a 0.00% rate of return.

Steven Kopits: “Greek participation in the Euro Zone facilitated this borrowing spree by providing low interest rates.”

I think what you intended to say was that German participation in the Euro Zone facilitated a reckless lending spree by greedy bankers searching for higher interest rates.

Slug,

Thanks for the info on Mirrlees. I was interested in his supply side leaning when he won his Nobel.

Could you give me a source for you supply side insights? Not saying you are wrong, I just would like to see who you consider a supply side authority.

Joseph –

I meant that Greek participation in the Euro Zone lowered Greek borrowing costs, because of the belief that the EU would never let a Euro Zone member default on a loan. This is turn allowed Greece, I believe, to borrow more than it could have in drachma.

Sweet made up multiplier numbers.