The effects on labor standards and trade

Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution written by Isao Kamata, Assistant Professor of Public Affairs and Economics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. This post is based upon this working paper; the paper also circulates as a Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) discussion paper.

The recent progress of economic globalization has been intensifying public concerns about the negative impacts of international trade on conditions of workers (such as a ‘race to the bottom’). These concerns are often linked to the idea of including in a trade agreement “labor clauses,” that is, provisions that require or urge the signatory countries to commit to maintaining a certain level of labor standards and/or allow the countries to use trade sanctions against their trading partners for their low labor standards or non-compliance of the standards. Having their proposals to add labor provisions to the multilateral trade agreement under the GATT/WTO system being unsuccessful to date, some countries such as the U.S. and EU are now seeking opportunities to include labor clauses in bilateral or plurilateral trade agreements (or regional trade agreements: RTAs).

The primary (or at least ‘official’) goal of a government’s including labor provisions in a RTA should be to prevent the country’s labor conditions from deteriorating or to even improve them. However, including labor provisions in a RTA might bring some policy costs to the government: for instance, only limited RTA partners might be willing to include labor provisions; negotiation for a RTA with labor provisions might take longer time; or the partners might be able to agree only with a limited degree of trade liberalization if negotiating labor provisions together. In these possibilities, the government might lose potential benefits from earlier or deeper trade liberalization that it could gain if they negotiated the RTA without labor clauses.

This paper empirically examines the following two questions: (i) Is including labor clauses in a RTA effective to maintain or improve domestic labor conditions in the signatory countries? (ii) Is a RTA with labor clauses equally trade-promoting to a RTA without labor clauses (in other words, does including labor clauses in a RTA not reduce the trade-enhancing effect of the RTA compared to the case in which the RTA does not include labor clauses)? The study starts by reviewing more than 200 RTAs that are currently in force and classifying them into six categories depending on the existence, nature, and extent of labor clauses in those RTAs. Then, dividing the RTAs into two broader categories—the ones with effective labor clauses and those without, the paper conducts empirical analyses for the two questions (i) and (ii), using (unbalanced) panel data for up to 220 countries for the period of years 1995 through 2012. In the analysis for (i), labor conditions are measured by three “outcome” measures (earnings, work hours, and occupational injury rate) and one “standard” measure (the number of the ILO’s core conventions ratified). In the analysis for (ii), trade growth is measured by an increase in bilateral trade volumes.

Through these analyses, the paper finds the following:

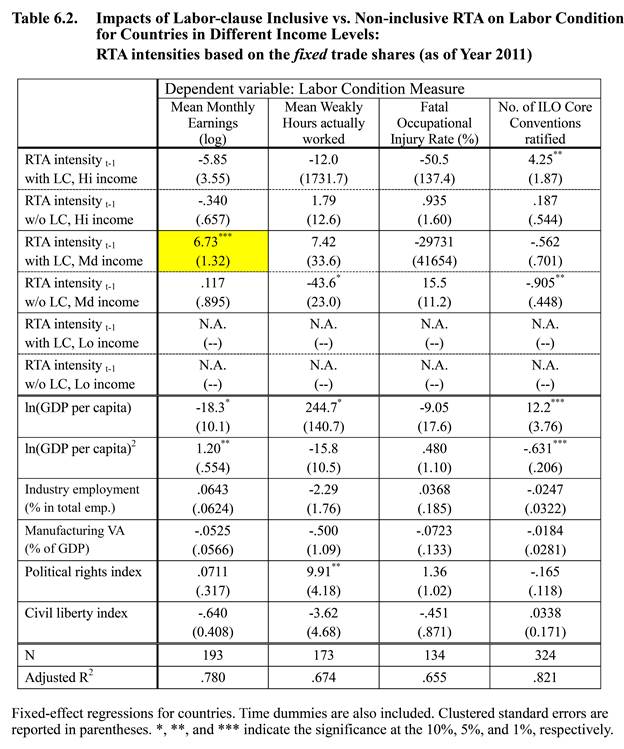

(i) Intensive trade with the partner(s) of a labor-clause-inclusive RTA may have a positive impact on labor earnings (but not on other labor-condition measure), but the effect should be concentrated on middle-income countries.

Source: Kamata (2014).

The highlighted entry in Table 6-2 indicates that as a middle-income country raises the share of trade with its labor-clause-inclusive RTA partner(s) in the country’s total trade by 1%, the real monthly earnings of the average worker in the country increases by 7%.

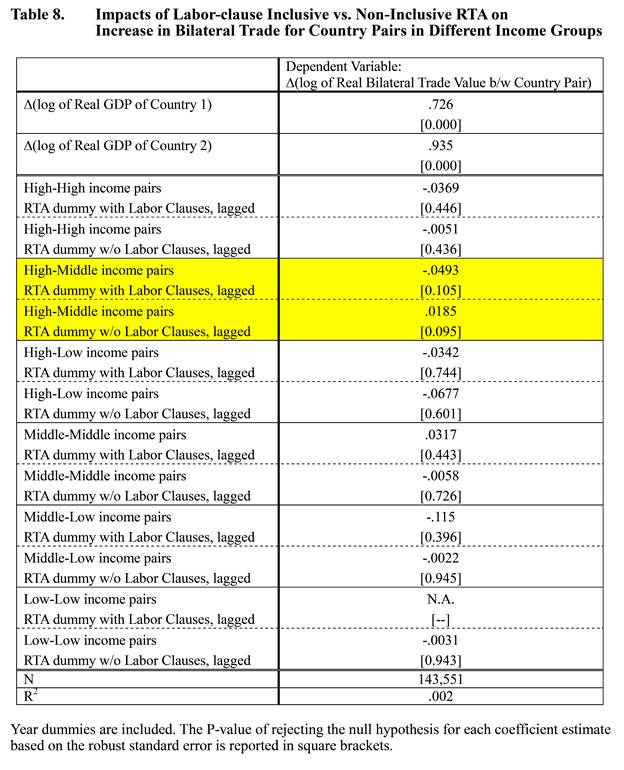

(ii) A RTA with labor clauses may reduce a trade-growth effect of the RTA for the middle-income countries, especially when their RTA partner is a high-income country.

Source: Kamata (2014).

The highlighted entries in Table 8 indicate that the rate of growth in trade between a high- and middle-income countries would be on average 1.9% higher when the countries had signed a RTA compared to the case of no RTA, but the trade growth rate would be lower by 4.9% than the no-RTA case if the RTA included labor clauses.

These results provide the policy implication that the inclusion of labor clauses in a trade agreement involves non-negligible costs (lower trade growth) in exchange for possible benefits (higher labor earnings) that may not be expected for every country. Putting it a little boldly, high-income countries, which are often eager to include labor clauses in a RTA, might have to incur the cost of a reduction in trade growth for no significant benefits in their domestic labor conditions.

The paper can be found here.

This paper written by Isao Kamata.

It’s interesting that German workers regard the U.S. as a third-world labor country and are trying to bring labor protections to the Tennessee VW workers.

Kamata starts with this misconception: “..the negative impacts of international trade on conditions of workers (such as a ‘race to the bottom’).” Its not a race to the bottom but a shift to the middle. Only those above the middle object and who might they be? The trade unions.

Menzie,

I’m shocked you’d post something like this. Seems to me that this is a lot like the minimum wage arguement.

Since US peak crude oil production per capita in 1970, production has declined 50% (40% since the secondary peak in 1985), coinciding with a decline in labor returns to GDP to record lows of the Great Depression.

In the meantime, private debt is at a record high to GDP and at an unprecedented 8-9 times private wages, resulting in net interest obligations and associated flows to the financial industry exceeding the annual growth of GDP.