On the release of the Productivity and Costs release, the WSJ reports “Weak Productivity, Rising Wages Putting Pressure on U.S. Companies: Economists fret how trends may affect inflation and broader growth”.

When wage compensation outruns productivity, the result is an acceleration in labor costs per unit of output. In the first quarter, those costs rose 4.5% at a yearly rate and 3% from a year earlier. If companies can’t boost productivity, they must either absorb the costs in their profit margins or raise prices.

Corporate profits are being squeezed as a result, and the worry is that companies will slow hiring and further slash spending.

A different worry for the Fed is that firms will react to higher labor costs by raising prices, pushing inflation above the central bank’s 2% target.

I don’t disagree, but I think these developments can be cast in a slightly different light.

Ceteris paribus, lower productivity growth does imply faster inflation. And in any case, low productivity growth is nothing to cheer about.But I think we don’t want to think about faster wage growth as necessarily resulting in faster inflation.

Consider the price level. By definition:

p = μ + ulc

where p is the log price level, μ is the log price-markup ratio, and ulc is the log unit labor cost. Taking the time derivative yields:

π = Δulc

if the markup is constant. π is the inflation rate. The key issue is the constancy of the markup.

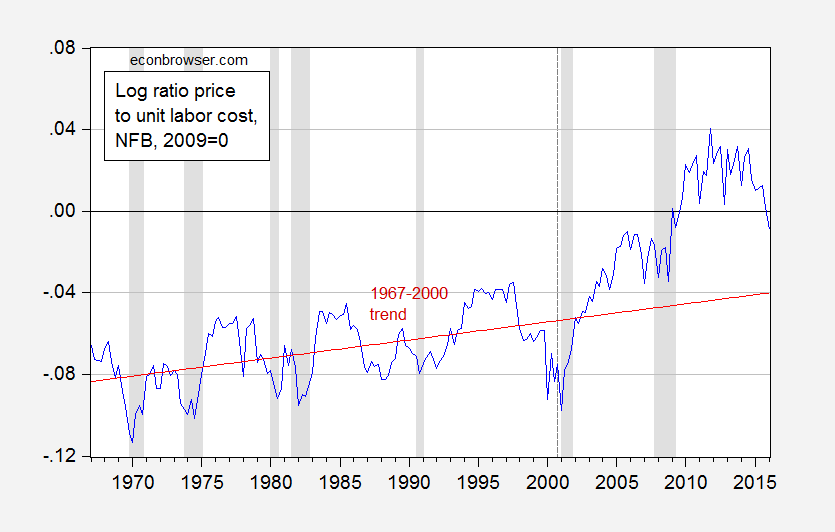

Figure 1 depicts a proxy measure for the nonfarm business sector’s μ.

Figure 1: Log ratio of implicit price deflator to unit labor cost in nonfarm business sector. Red line is trend estimated over the 1967Q1-2000Q4 period. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER and author’s calculations.

There is a linear trend in the ratio until 2000, at which time there appears to be a break in the relation; the price level rises relative to unit labor cost, i.e., the markup increases. One can loosely interpret this as a rise in capital’s share (in fact, this variable is the exact inverse of the labor share of the NFB as calculated in the Productivity and Cost release).

More formally, over the 1967-2000 period, (log) price and unit labor costs are cointegrated (according to the Johansen maximum likelihood cointegration test, allowing for a linear trend in the data). The cointegrating vector is (1 -1.02), borderline significantly different from (1 -1).

Over this period, unit labor costs adjusts to the disequilibrium, while the price level does not.

In contrast, this relationship does not appear to hold over the post-2000 period, according to formal cointegration tests (although that might be because the sample is too small). It doesn’t appear to hold over the entire 1967-2016 sample either.

Obviously, unit labor costs cannot continue to rise faster than prices indefinitely. However, there is some way to go before the ratio converges to the 1967-2000 trend.

So…one way to interpret the recent slowdown in productivity, acceleration in compensation growth, in the presence of quiescent inflation is that it represents a reversal of the deviation that started in the early 2000’s.

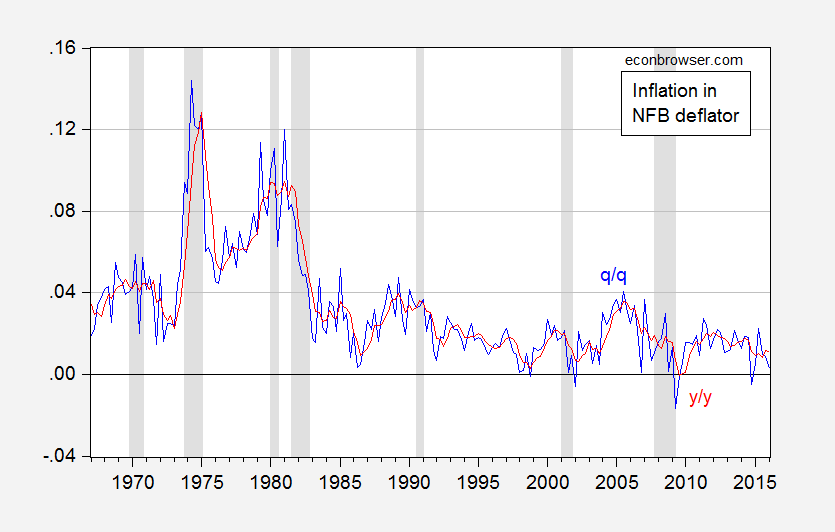

For reference, here are the inflation rates (measured using the implicit price deflator) for the nonfarm business sector.

Figure 2: Inflation rate of the implicit price deflator in the nonfarm business sector, quarter-on-quarter (blue), and year-on-year (red), annual rates calculated as log differences. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER and author’s calculations.

As of 2016Q1, year-on-year inflation is 1.1%, and quarter-on-quarter is 0.3%.

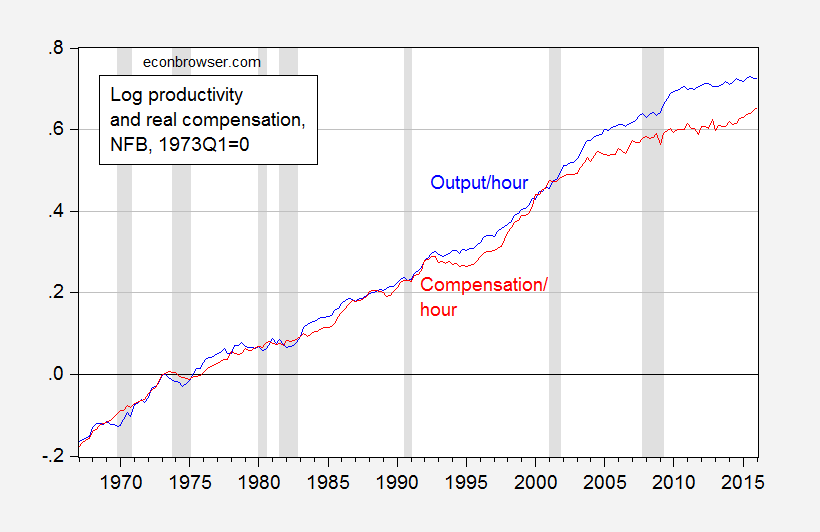

Digression: The Heritage Foundation’s James Sherk has recently argued that real compensation and productivity track each other very well, and presents this graph to prove his point. (He argues that other studies have inappropriately used differing deflators and measures with different sectoral coverage to obtain misleading inferences.) Clearly, my conclusions shown above are at variance with Mr. Sherk’s conclusion. What’s going on?

Using quarterly data over the same sample (extended to 2016Q1), and a different (log) scale, I show that a gap has widened between the two series, even for the NFB sector, and using the same deflator.

Figure 3: Log real output per hour (blue), and compensation per hour (red), in nonfarm business sector, normalized to 1973Q1=0. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER and author’s calculations.

In fact, since 2001Q1, the cumulative growth divergence widened from 0 to as much 11% in 2010Q4, before shrinking to 6% in 2016Q1.

In the Information Revolution before 2000, the market invested to fuel revenue growth of emerging firms, which built-up entire new industries. After 2000, there was a creative-destruction process mostly from 2000-02 and the market invested to generate huge profits in those new industries. Consequently, the U.S. not only leads the world in the Information Revolution, it leads the rest of the world combined (in both revenue and profit).

Profits Without Production

Paul Krugman

June 20, 2013

“Economies do change over time, and sometimes in fundamental ways.

“…the growing importance of monopoly rents: profits that don’t represent returns on investment, but instead reflect the value of market dominance.

…consider the differences between the iconic companies of two different eras: General Motors in the 1950s and 1960s, and Apple today.

G.M. in its heyday had a lot of market power. Nonetheless, the company’s value came largely from its productive capacity: it owned hundreds of factories and employed around 1 percent of the total nonfarm work force.

Apple, by contrast…employs less than 0.05 percent of our workers. To some extent, that’s because it has outsourced almost all its production overseas. But the truth is that the Chinese aren’t making that much money from Apple sales either. To a large extent, the price you pay for an iWhatever is disconnected from the cost of producing the gadget. Apple simply charges what the traffic will bear, and given the strength of its market position, the traffic will bear a lot.

…the economy is affected…when profits increasingly reflect market power rather than production.

Since around 2000, the big story has been one of a sharp shift in the distribution of income away from wages in general, and toward profits. But here’s the puzzle: Since profits are high while borrowing costs are low, why aren’t we seeing a boom in business investment?

Well, there’s no puzzle here if rising profits reflect rents, not returns on investment. A monopolist can, after all, be highly profitable yet see no good reason to expand its productive capacity.

And Apple again provides a case in point: It is hugely profitable, yet it’s sitting on a giant pile of cash, which it evidently sees no need to reinvest in its business.

Or to put it differently, rising monopoly rents can and arguably have had the effect of simultaneously depressing both wages and the perceived return on investment.

If household income and hence household spending is held down because labor gets an ever-smaller share of national income, while corporations, despite soaring profits, have little incentive to invest, you have a recipe for persistently depressed demand. I don’t think this is the only reason our recovery has been so weak — but it’s probably a contributory factor.”

As regards your last graph–output per hour & compensation per hour–a Robert Lawrence post, https://piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/growing-gap-between-real-wages-and-labor-productivity, contains his graph 5, which adjusts output for depreciation and compensation for a business sector price deflator. That graph appears to show a smaller gap between productivity and compensation, at least up to about 2010, than your graph. Have you thought about the points he has made on this issue?

It should be noted, more workplace regulations, easier lawsuits, and less negative externalities aren’t included in compensation, but benefit workers.

Certainly, the workplace is much better than the 1970s and more expensive restrictions were added recently, particularly in some industries.

Gene: Good point. However, as he notes in the post referring to Figure 5, even after accounting for more rapid depreciation of capital in recent times, the gap post-2008 is substantial, and merits further research. Lawrence’s Working Paper goes into greater detail for his explanation post-2008. I don’t have any particular insights into whether the gross substitutes or gross complements view is more appropriate. And I’m not sure how to differentiate between his explanation and one based on variations in bargaining power.

The rapid reversal post-2013 in the gap (using the official, unadjusted for depreciation, data) suggests to me that at least some component of the gap is due to something other than the neoclassical factors he lays out in his working paper.

I encourage you to expand the model. You get a decent markup measure by looking at the increase in the price deflator vs. the increase in costs. When you compare the price deflator to unit labor costs the picture is very different from comparing the price deflator to total unit costs. other costs matter, too. For a big picture look, take domestic nonfinancial corporate profits before tax divided by the corresponding gross value added — this creates a good profit margin proxy. You will see the 05 – 15 margin looks very high compared to 80 – 05, but rather normal compared to 50 – 80. So, is the recent period margin high or was the 80 – 05 period unusually low? Note, since the domestic share of total profits has declined 15 percentage points since the early 60s, it is important to use domestic profits rather than total.

The Heritage Foundation’s James Sherk’s argument is basically “If we include high level managers and the other highest paid outliers, the productivity and wages almost track exactly.” From the write up “Among the excluded are the majority of the most highly paid workers in America. This makes a large difference: Over the past generation, compensation has risen faster among high earners than in the rest of the economy. ”

No duh. Income inequality has made it such that the majority of workers have not seen an increase in pay as compared to their productivity. Again, from the write up:

“Across the overall economy, productivity has increased by 58 percent since 1979.[45] Household labor compensation has also grown—but at quite different rates across the income distribution. Labor compensation in the bottom quintile grew by 58 percent; almost exactly in pace with productivity growth. Average compensation in the top quintile grew somewhat faster—by 69 percent. But average compensation in the second, middle, and fourth quintiles grew much less than average productivity—by 20 percent, 18 percent, and 32 percent, respectively.[46] Pay closely tracks productivity across the economy. But many workers’ pay has grown at less than the average rate of productivity growth.[47]”

Out of 5 quintiles, 3 have seen their pay increase by between 26% to 40% less than productivity increased while the top quintile’s pay grew 11% faster than productivity growth. The bottom grew exactly at the rate of productivity (I presume any gains to the lowest quintile were mostly from non-market income transfers).

This whole study is basically Bill Gates-in-a-bar. The bar is across from a factory that closed, but don’t worry, Bill Gates just walked in so if we take a measure of everyone in the bar the average income has skyrocketed!

Importing a poor foreign city into your city will lower the average.

My biggest concern is the West getting crowded and water drying-up.

Anyway, crony-capitalists are doing fine. What about small business owners?

peak, when discussing crony-capitalists, what are your views on defense spending and the defense contractors. we have boeing, lockheed, northrup, etc capturing billions of dollars in government contracts for defense spending. do you propose a reform of defense contractor spending?

We have to maintain a national defense infrastructure, although defense spending as a percent of GDP has been in a long decline. Less waste, fraud, and abuse should be a goal.

would you agree with the statement that a significant amount of waste and abuse exists on the part of defense contractors? these are extremely profitable companies drinking directly from the taxpayer well. my brother worked in the business for over a decade, and the stories i would hear will make your stomach churn. corporate welfare run amok.

The

BLS does not include stock options in it’s measure of compensation. Consequently, the BLS measures significantly understate the compensation of the highest paid employees.

More Nonsense by WSJ: “A different worry for the Fed is that firms will react to higher labor costs by raising prices, pushing inflation above the central bank’s 2% target.”

Firms cannot unilaterally raise prices, period. Any Keynesian knows that firms can only raise prices in response to excess demand. Why isn’t it obvious to the WSJ that all firms all the time would raise prices if they could do so? That is simply Business 101, but fools who write for the WSJ apparently are ignorant of basic business concepts. Unless demand is rising, firms that raise prices will simply lose sales to competitors who don’t.

Yes,, but note that the ISM indices of prices and deliveries ( the share of firms reporting slower deliveries) have both moved up sharply in recent months.

This suggest we may be closer to full employment or capacity utilization than you think.

The jump in the deliveries suggest we should be watching more for demand pull rather than cost push inflation than the Fed and others are doing.

Another potential explanation for the slowing in deliveries is that producers have exercised great restraint on inventories and are so in a poor position to mean increases in demand. A bottleneck that can be resolved by increasing inventory spending is less likely to push up inflation than a more broadly based capacity constraint.

Record income inequality in labor’s share of GDI is also due to less progressive taxation policies…don’t forget that before R Reagan maximum income tax bracket rate was 70 + percent, and there were fewer tax loopholes, overseas shelter scams to hide monies. The supply-sider, anti-gov types institutionalized tax scams by not enforcing tax laws, dowsizing the IRS, etc.

Tax rates don’t matter much. What’s important is tax revenue. There was much more tax avoidance when tax rates were high. Taxes have become more progressive:

CBO: Top 40% Paid 106.2% of Income Taxes; Bottom 40% Paid -9.1%, Got Average of $18,950 in ‘Transfers’

December 9, 2013

“The top 40 percent of households by before-tax income actually paid 106.2 percent of the nation’s net income taxes in 2010, according to a new study by the Congressional Budget Office.

At the same time, households in the bottom 40 percent took in an average of $18,950 in what the CBO called “government transfers” in 2010.

The households in the top 20 percent by income paid 92.9 percent of net income tax revenues taken in by the federal government in 2010, said CBO.”

And, of course, it’s not surprising income inequality increases when there’s a boom in both high-skilled and low-skilled people in the U.S..

Rising riches: 1 in 5 in U.S. reaches affluence

December 6, 2013

“New research suggests that affluent Americans are more numerous than government data depict, encompassing 21% of working-age adults for at least a year by the time they turn 60. That proportion has more than doubled since 1979.

Sometimes referred to by marketers as the “mass affluent,” the new rich make up roughly 25 million U.S. households and account for nearly 40% of total U.S. consumer spending.

In 2012, the top 20% of U.S. households took home a record 51% of the nation’s income. The median income of this group is more than $150,000.”

The bottom 40% of incomes includes lots of households living off of savings and Social Security. Social Security is a transfer, but a transfer paid for largely by the recipient. Income taxes do not include FICA, which pays for Social Security. Bad case of apples and oranges in putting income tax on one side of the ledger, transfers on the other.

If you include all payments from households to the government, including sales taxes, state taxes, FICA and other types of fees, the top 40% does not pay over 100%. Far from it. If, on the other hand, you leave out Social Security payments, “transfers” amount to far less than $18k per year.

a better distribution of income increases across wage groups would certainly improve the situation. the fact that higher salary cohorts pay for a large share of tax revenue gets stated in a way that misleads what is happening in america. the upper incomes have gained a disproportionate share of income increases-it is only logical their share of taxes paid will increase accordingly. for one to argue higher income folks are paying too much in taxes, so their tax burden should fall towards the lower incomes, is actually striking low incomes twice. once when they were passed over for income gains, and again when they are taxed additionally in the name of “fairness”. the issue of class warfare is a direct result of this two step process, which has resulted in too much wealth being accumulated into a too small cohort of americans. it is kind of like when the boss says we will have across the board pay raises of 2% as a means to be fair to everybody in the slow economy. such an approach is unfair to the entry levels and biases towards the higher ranking decision makers-but who is willing to point out to the boss his approach is inherently unfair and biased to the already wealthy in the company?

And we should insist that these reports show public finance contributions as a percent of net worth.

It is just sophistry to allow people to only make income tax representations where by its very nature you have to have decent income to get into a taxable base, on this limited calculation if what constitute economi capacity.

Commenters need to look for percent of net worth data before apologizing for people who also have great net worth. Right, it is just an apologia, sophistry, and illegitimate as a basis for policy discussions. Imo.

Tax rates don’t matter much, and there was more tax avoidance when rates were high? Not sure I follow. If rates don’t matter, then why does avoidance respond to rates?

And where’s your evidence that tax avoidance is higher when rates are higher? I realize that’s what anti-tax types claim, but where’s the evidence? The IRS estimates that tax evasion cost $458 billion per year between 2008 and 2010, more than the entire deficit. That looks pretty high, and evasion is only one form of avoidance.

I was responding to the statement that assumes higher tax rates imply more tax revenue. Tax avoidance is legal. Tax evasion is illegal. Why work more hours, for example, when the government takes almost all the marginal income?

it doesn’t seem fair the top 40% pays 106.2% of income taxes.

Doesn’t seem fair that the top 40$ pays 106.2% of income taxes unless you think about it. The 106.2% number is, after all, just an abstraction until you put it in context. Income taxes are only one kind of taxes, really the only progressive form of taxation at any level of US government. I noted that those at the low end pay most of the other forms of taxation. You ignored the point. If you actually have a case, you shouldn’t have to ignore facts to may that case.

Tax avoidance is legal, unless it isn’t. As noted earlier, tax evasion is tax avoidance. I’s the kind of tax avoidance that’s illegal. To pretend otherwise, and to ignore the point when others make it, seems a bit…odd. So does your suggestion that government “takes almost all the marginal income”. That’s simply untrue. So, do you have evidence that tax avoidance is higher when tax rates are higher? More importantly, do you have evidence that higher rates bring in no more revenue than lower rates, due to avoidance? The deficits of the Reagan and Bush Jr. episodes pretty strongly suggest that cutting rates leads to a reduction in revenue relative to the same economy with higher rates.

Over 90% of federal revenue comes from income taxes, corporate taxes, and payroll taxes, which employers match Social Security and Medicare.

There are optimal tax rates, that aren’t too high or too low, to maximize tax revenue. See the economics literature.

“it doesn’t seem fair the top 40% pays 106.2% of income taxes.”

its not fair, until you recognize most of the income increases in the past decades has also gone to the upper income groups as well. what is not fair, is for the higher incomes to continue to gain a disproportionate amount of overall income while lessening their tax burden. you cannot continue to gain income share and then argue you shouldn’t be paying more taxes, unless you want to burden the poor twice.

a quick summary of the tax and income distribution should end any thoughts that higher incomes are taxed too much. you cannot triple your income and complain you are paying an unfair share of taxes.

http://money.cnn.com/2016/06/08/news/economy/top-1-income/index.html?iid=hp-stack-dom

Baffling, why don’t you work three times harder to triple your income and pay your fair share?

Or learn a skill to create three times more value for society, since income = GDP = output, and produce your fair share?

So, triple your income and don’t complain about paying your fair share.

I want you to do your fair share to pull-out of this depression and reduce budget deficits.

“Baffling, why don’t you work three times harder to triple your income and pay your fair share?”

you honestly believe the top 20% have simply worked three times harder in order to obtain that income increase? apparently the poor are simply lazy, and if only they would work more they would have a greater income. you are oblivious to how inequality occurs in a society, probably because you were somebody whose job actually promoted that inequality. too bad not everybody could live your charmed life.

Fatal defects of profit and market theory

Comment on Menzie Chinn on ‘Thinking about Wages, Inflation and Productivity… and Capital’s Share’

Economists are groping in the dark with regard to the two most important features of the market economy: (1) the profit mechanism, and (2), the price mechanism. The fault lies in the fact that economists argue from the micro level upwards to the economy as a whole. And here the fallacy of composition regularly slips in. To get out of failed standard economic theory requires to move from microfoundations to macrofoundation. In other words, the faulty axiomatic foundations of standard economics have to be fully replaced.

In the following a sketch of the formally and empirically correct price, employment, and profit theory is given. The most elementary version of the objective structural employment equation reads:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AXEC62.png

From this equation follows:

(i) An increase of the expenditure ratio rhoE leads to higher employment (the letter rho stands for ratio). An expenditure ratio rhoE>1 indicates credit expansion, a ratio rhoE<1 indicates credit contraction.

(ii) Increasing investment expenditures I exert a positive influence on employment, a slowdown of growth does the opposite.

(iii) An increase of the factor cost ratio rhoF=W/PR leads to higher employment.

The complete and testable employment equation is a bit longer and contains in addition profit distribution, public deficit spending, and import/export.

Item (i) and (ii) cover Keynes’s arguments about aggregate demand. Here, the focus is on the factor cost ratio rhoF as defined in (iii). This variable embodies the price mechanism which, however, does not work as the representative economist hallucinates. As a matter of fact, overall employment INCREASES if the average wage rate W INCREASES relative to average price P and productivity R.

For the relationship between real wage, productivity, profit and real shares see (2015, Sec. 10)

The correct profit equation reads: Qm = Yd+I-Sm (2014, p. 8, eq. (18)).* Legend Qm: monetary profit, Yd: distributed profit, Sm: monetary saving, I: investment expenditure.

The profit equation gets a bit longer when foreign trade and government is included. The equation says:

(iv) Strong growth = high investment I is good for the overall monetary profit of the business sector as a whole.

(v) Strong consumption expenditures = low saving Sm or even dissaving -Sm = growing consumer debt is good for profit.

(vi) By implication high government deficit spending = growing public debt is good for profit.

(vii) High profit distribution Yd is good for profit.

Profit and profit distribution constitute a self-reinforcing feedback loop. The same holds for profit and investment.

Note, that OVERALL profit and by consequence the income distribution has NOTHING to do with productivity or low wages or market power. These and other factors affect only the DISTRIBUTION of overall profit BETWEEN firms. What holds on the firms’ level does NOT hold for the economy as a WHOLE. Not to realize this is the fatal standard error of standard thinking about wages, distribution, inflation, productivity, and employment.

The ultimate cause of unemployment is the proven scientific incompetence of economists since more than 200 years.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2014). The Three Fatal Mistakes of Yesterday Economics: Profit, I=S, Employment. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2489792: 1–13. URL

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2489792.

Kakarot-Handtke, E. (2015). Major Defects of the Market Economy. SSRN Working Paper Series, 2624350: 1–40. URL

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2624350.

* Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AXEC09.png or https://

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AXEC08.png or https://commons.wikimedia.

org/wiki/File:AXEC42.png