Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Serkan Arslanalp, senior economist at the IMF. This post is based on the paper by the same title, coauthored with Wei Liao, Shi Piao, and Dulani Seneviratne (all of the IMF).

China’s economy leaves nobody indifferent. The world is watching closely as the second largest economy in the world is shifting its growth model from an export-driven one to one centered on household consumption. As China’s economy slows and rebalances, its impact is being felt on an already fragile global economy, and particularly in the rest of the Asia region. Our recent study examines how China’s rebalancing is affecting Asian financial markets.

A significant partner

Because of its sheer size and integration into the global economy, China’s transition will certainly affect those around it. China is now the top trading partner of most major economies in the region, particularly in East Asia and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). During 2000–15, exports to China increased dramatically from 3 percent to 9 percent of world exports and from 9 percent to 22 percent of Asian exports. According to IMF staff calculations, a 1 percentage point change in China’s real GDP growth is estimated to affect the real GDP growth of the median Asian economy by 0.15–0.30 of a percentage point.

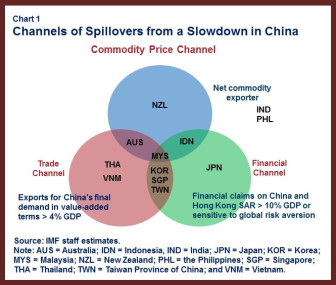

Against this backdrop, some countries have felt the pinch. As China’s economy moves away from investment, its demand for raw materials used intensively in related activities, such as iron ore, copper, and coal, is declining contributing to lower commodity prices. Commodity exporters such as Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and New Zealand are likely to be hard hit.

Beyond that, those economies that have been closely integrated with China through the global value chains, and which are heavily exposed to China’s investment activity, such as Korea and Taiwan Province of China, will be affected. Suppliers of technology like Japan and Korea, and providers of capital, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, will also feel the pain.

Finally, financial connections are also growing. Financial spillovers from China to regional markets are on the rise, in particular in equity and foreign exchange markets, driven by greater trade links with China (see Chart 1). In addition, several economies, such as Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan Province of China, have significant financial links with China, both directly and through Hong Kong. Overall, financial markets are likely to become more sensitive to shocks from China as these links develop further, including with the ongoing internationalization of the renminbi and China’s gradual capital account liberalization.

Co-movements in Asian markets: A first glance

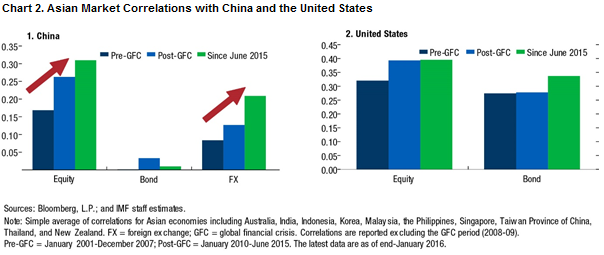

Broadly, the correlation of Asian asset returns with China has risen over time. Chart 2 presents the average correlation of returns in Asian markets with those in China for equity, foreign exchange, and bond markets. It is clear that even before the market turbulence in the summer of 2015, the co-movement of Asian and Chinese markets was rising. Compared with the period prior to the global financial crisis, the region’s asset return correlations with China have increased in both equity and foreign exchange markets. In contrast, Asia’s bond markets have remained uncorrelated with the Chinese bond market, which may reflect the relatively isolated nature of the Chinese bond market, as well as the preeminence of advanced economy financial conditions in driving global bond markets (IMF, 2014). (A recent empirical study by the IMF found that financial conditions in advanced economies explain nearly half of the variation in bond flows compared with about a fifth of the variation in equity flows).

China’s financial spillovers: Going a step further

We evaluate the statistical significance of the relationships apparent in Chart 2 by employing an estimation process similar to that of Forbes and Chinn (2004). The estimation is composed of two steps. First, we investigate the degree of sensitivity of stock market returns to global, cross-country, and domestic factors. Second, treating the estimated sensitivity (or “beta”) to center economies as a dependent variable, we examine its determinants among variables that reflect countries’ trade and financial linkages with the center economy.

We extend the Forbes and Chinn (2004) approach in several ways. First, we include China as a “center” country, given that it is now the world’s second largest economy. In particular, the center economies in our paper include the four largest economies in the world as ranked by GDP: China, Japan, euro area, and the United States (as in Aizenman and others, 2016). Second, to measure trade linkages more accurately, we move away from the conventional gross trade data and rely on value-added trade data that have become available. (As the global supply chain has become spread over countries, gross trade data can be misleading, as it does not correctly represent where the final demand is. This is a particularly important for China given its status as the “World’s Factory.”) Third, given the availability of new data, we use a more comprehensive measure of financial linkages between countries, which include all types of cross-border claims (portfolio, bank, and FDI). We also account for the role of Hong Kong SAR as a financial gateway to China. Annex 2 of our study provides further details on the construction of the dataset used in the analysis.

Regression results

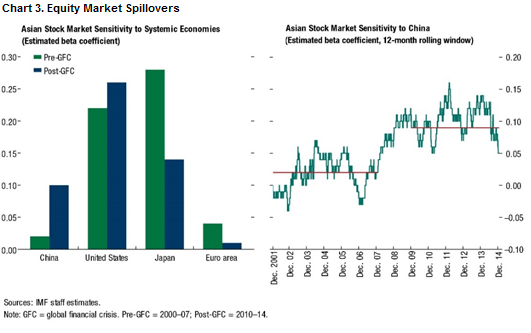

The results of the first-stage regressions suggest that, on average, China’s influence on Asian financial markets has risen after the GFC, although still lower than of the United States (see Chart 3). China’s spillover coefficient is positive and significant for all Asian economies in our sample. In contrast, the spillover coefficient for Japan has declined after the GFC and was similar to that of China as of end-2014. Chow tests indicate that changes in the spillover coefficients before and after the GFC are statistically significant for both China and Japan.

The results of the second-stage regressions suggest that the trade exposure is the main transmission channel for spillovers from China into Asian equity markets. At the same time, the relative contributions of trade and financial linkages in explaining the variation in spillovers from China have changed since the GFC. In particular, while trade linkages explained more than 90 percent of the variance before the GFC, they now explain around 60 percent of the variation, with the rest explained by financial linkages. Hence, it appears that Asia’s financial linkages with China have become an additional transmission channel for spillovers in Asia, in particular after 2010. This may partly reflect the internationalization of the renminbi, which started in 2010. (Robustness tests suggest that financial linkages with China is significant notably when they are measured inclusive of Hong Kong, SAR. This highlights the important role of Hong Kong, SAR as a financial gateway to China.)

To sum up

Overall, we find that financial spillovers from China to regional markets are on the rise. The main transmission channel appears to be trade linkages, although direct financial linkages are playing an increasing role. Without an impact on global risk premiums, China’s influence on regional markets is not yet to the level of the United States, but comparable to that of Japan. If China-related shocks are coupled with a rise in global risk premiums, as in August 2015 and January 2016, spillovers to the region could be significantly larger. Over the medium term, China’s financial spillovers could rise further with tighter financial linkages with the region, including through the ongoing internationalization of the renminbi and China’s capital account liberalization.

This post written by Serkan Arslanalp.