Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written Ines Buono and Sara Formai (Banca d’Italia) summarizing their chapter published in the book International Macroeconomics in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis edited by L. Ferrara, I. Hernando and D. Marconi. The views expressed here are those solely of the author and do not reflect those of their respective institutions.

Business fixed investment has been persistently weak in advanced economies since the Global Financial Crisis: nine years after its outburst, the investment-to-GDP ratio was still almost 3 percentage points lower, on average, than its pre-crisis level of 24 per cent. Although the downturn was comparable with past experiences of financial crisis, the recovery was highly heterogeneous across countries, and especially slow for those hit by the European sovereign debt crisis in 2011.

Recent empirical works have tried to identify the relative roles played by different factors in holding back aggregate investment (see, e.g., Lewis et al. (2013), IMF’s WEO chapter 4 (2015), Barkbu et al. (2015)). According to a conventional model combining an accelerator and a neoclassical approach, investment is a function of aggregate output and the user cost of capital. In addition, although the adverse role of uncertainty for investment has long been acknowledged (see, e.g., Bernanke (1983) and Guiso and Parigi (1999)), recent contributions have confirmed the importance of considering uncertainty in both micro and macro investment equation (see, e.g., Bloom (2009), Meinin and Roehe (2017)). Finally, Bussiere et al. (2015) have proposed a ”forward-looking model” (as opposed to a backward-looking one), where they proxy aggregate output with expectations of future demand, showing that this variable improves explanations of investment with respect to previous approaches.

In this chapter we study whether the response of investment to these factors has changed over time, especially after the outbreak of the 2008-2009 crisis. We consider a panel of 19 countries from 1990 to 2016. We measure demand by one-year-ahead forecast GDP, uncertainty by realized financial market volatility and user cost of capital by the product of the borrowing cost of capital and investment relative price. After testing how the benchmark model performs, we study how its main parameters have changed over time. We first test the hypothesis of a structural break, generally during the 1990-2016 period, and specifically in 2008. We then perform a series of analyses in which the parameter of each determinant of investment is allowed to be time-varying. Finally, we check whether our findings are common to all the cross-sectional units, or whether the countries more severely hit by the crisis (peripheral European countries) were characterized by specific dynamics.

Our main findings may be summarized as follows:

- Although in the overall sample each determinant of the model has a statistically significant role in explaining investment, their relevance change over time;

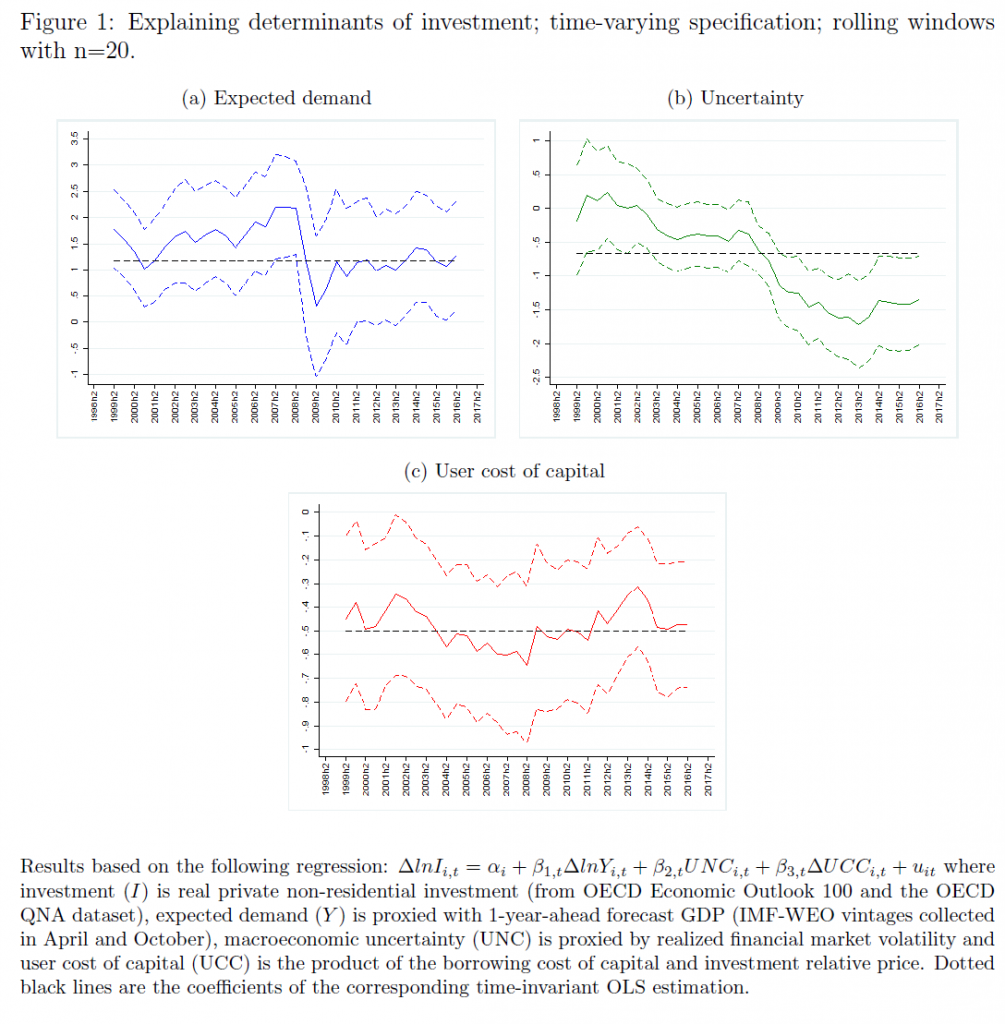

- Expected demand is a significant factor in the entire sample period but its relative importance has been higher in the years before the crisis (fig.1, panel a). On the contrary, macroeconomic uncertainty becomes a significant component of investments only after the crisis (fig.1, panel b). Finally the role of the user cost of capital is constant all over the sample period (fig.1, panel c).

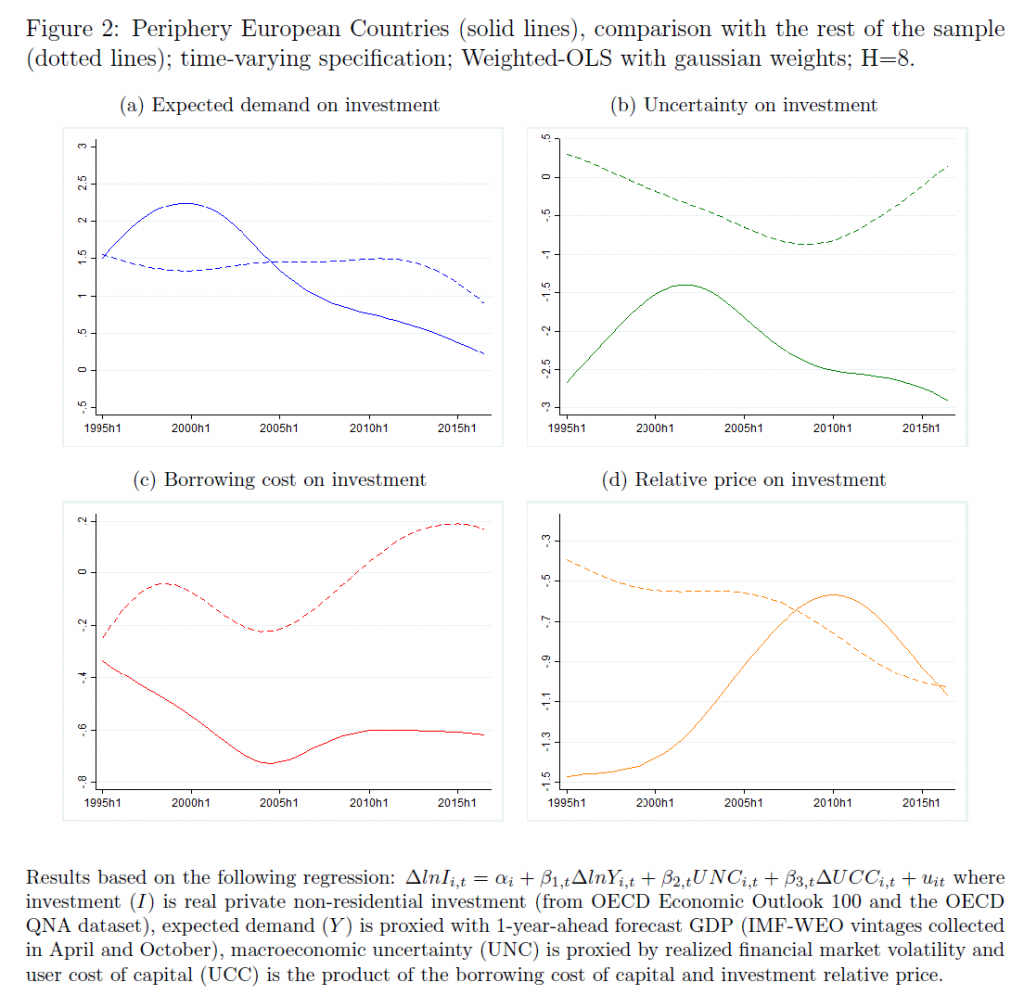

- Replicating the analysis for peripheral European countries we find that the sensitivity of investment to macroeconomic uncertainty becomes much higher in the aftermath of the crisis (fig. 2, panel b). Moreover, for these countries, the user cost of capital – and especially the borrowing cost component (fig. 2, panel c) – shows a stronger relevance in determining investments, especially in the aftermath of the crisis.

Our results suggest the following policy implications. First, monetary policy, by curbing interest rates and thus the user cost of capital, retains a key role as a way to stimulate aggregate investment, and this role has probably been crucial in preventing the recent crisis from having even more serious consequences for investment, especially in the hardest hit countries. Second, policies that stimulate aggregate demand (including, of course, monetary and fiscal policies) have an indirect positive effect on capital accumulation. Third, reducing uncertainty on financial markets also helps to create an environment that supports investment. In this respect, the central banks’ efforts to re-build confidence after the outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis and the European debt crisis may have been key in preventing a much deeper and more persistent collapse on business confidence and productive investment.

This post written by Ines Buono and Sara Formai.

Just when I thought Menzie no longer cared, he remembers what initiated our true bromance. FREE research papers. My heart flutters as my face gushes into a bright fuchsia. Right when I thought he had forgotten to care. “Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by research paper links of Formai and Buono”

Oh wait, this is only a unilateral relationship. It just dawned on me this is actually only my unrequited man-crush.

Speaking of love letters (and this isn’t meant to be derogatory in any way, just an observation), the above appears to be a love letter written to Mario Draghi.

This describes the difference between a depression and a recession, no?

A recession is when your neighbor gets laid off.

A depression is when you do.

I wistfully and hopelessly dream that one day the euphemism, “recession”, which is a post-WW2 creation, would be taken out our economic language. Or label all the minor depressions of the past as recessions – which as far I know, no major historian ever has.

@ SecondLook

I think your request, although I kind of understand your annoyance, is a little hard to fulfill. The problem being there is so much grey area in the actual accuracy of any economic number given, and in the fact even if you could pinpoint for certain some economic numbers (say if we knew for example with 100% accuracy unemployment was EXACTLY 5%), Even if the margin of error was plus/minus 0.0%, people would still have different subjective labels they would want to pin on that 5%. Republicans would probably say ALL that 5% are just “lazy bastards” and it has no systemic relation to the economy. Democrats would probably say we are losing economic productivity by those 5% doing nothing and acquiring no skills of their own. The end analysis is—what that 5% unemployment really means (even if known to be dead on accurate) could be argued literally to eternity.

“Banana” has also been tried as a substitute for “depression” and “recession”, but failed to gain acceptance.

I just wonder if the relationship between output and fixed investment might have changed as ‘brick-and-mortar’ establishments lose out to ‘e-tail.’ (Anecdotal examples: Netflix vs. Blockbuster; Kindle vs. Barnes and Noble; Amazon vs. retailers of all types…)

don Could you elaborate? I don’t think I understand your point. The BEA does now include intellectual property as a subcomponent of GDP under fixed nonresidential investment; although my understanding is that this doesn’t capture the use of IP, only the production of new IP. Or are you saying that since the marginal cost to produce from existing IP is near zero the relationship between output and the cost to produce from existing IP has broken down? In other words, what’s broken down isn’t the relationship between output and new investment, but between output and the cost to produce from existing capital.

The same analysis using equipment rather than fixed investment (leaving out business construction expenditures so leaving out brick-and-mortar) gives the same general result. Investment has been weak relative to demand growth, cost of capital and profits.

Yet what kinds of investments are made as a result of monetary policy reducing the user cost of capital and stabilizing financial markets after a crisis?

Uuuuuuhh, bonds??

Investment has been sluggish since the middle of 2000. Capitalism needs another industrial revolution of Digital revolution or its spent. In the latter case, living standards will slowly fall until people lose faith. The state will try and delay that as long as possible as seen by bailouts.