In my mind, absent a shooting war, the economy is headed for a slowdown, if not a recession. I am confident that, should the administration or anybody else propose countercyclical fiscal policy, a set of the usual suspects will deny the efficacy of discretionary policy. Hence, a prebuttal is called for.

A Typical Skeptic’s View

Here’s a quote from an article the last time the fiscal debate raged, in 2010. From Brian Riedl’s The fatal flaw of Keynesian stimulus (Washington Times):

Last week, the Congressional Budget Office released a report claiming that the $814 billion “stimulus” has added 3.4 million net jobs.

…

Such implausible analysis does not come from actually observing the post-stimulus economy. Rather, it comes from Keynesian economic models that have been programmed to conclude that government spending injects new dollars into the economy, thereby increasing demand and spurring economic growth. In other words, these models are programmed to conclude that stimulus spending always creates jobs and growth, no matter how the economy actually performs.

Well, not quite. As I described in this post, there are a variety of ways in which multipliers are obtained. Oftentimes, the impacts are estimated either directly or indirectly, by estimating the marginal propensity to consume. The article continues:

But there is one problem with the government stimulus theory: No one asks where Congress got the money it spends.

Congress does not have a vault of money waiting to be distributed. Every dollar Congress injects into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed out of the economy. No new spending power is created. It is merely redistributed from one group of people to another.

It is intuitive that government spending financed by taxes merely redistributes existing dollars. Yet spending financed by borrowing also redistributes existing dollars today. The fact that borrowed dollars (unlike taxes) will be repaid some years later does not change that.

Here, I think the author, Mr. Riedl, is invoking Ricardian Equivalence, despite the fact that there is no empirical evidence, to my knowledge, that validates pure Ricardian Equivalence (actually, Ricardian equivalence wouldn’t necessary hold for government spending on goods and services, anyway). Now, at this juncture, I thought that he might be invoking a real business cycle model, or an older, nonstochastic version of the RBC, namely a flex price Classical model. But then the next paragraph reads:

Some believe stimulus spending is the mechanism by which the Federal Reserve injects new dollars into the economy. Yet the Fed could run the printing press and then inject those dollars into the economy by buying existing bonds (with mostly inflationary results). It doesn’t need an expensive stimulus bill to conduct monetary policy.

Accepting that the Fed can stimulate via monetary policy then implies either (1) sticky prices so an expansionary monetary policy can affect the real interest rate, or (2) a financial accelerator model such that collateral constraints or some other financial rigidity holds. In the latter case, it seems prima facie that Ricardian Equivalance cannot hold.

Next, I was thrown for a loop, because Mr. Riedl seems to conflate real saving and the monetary multiplier. He argues that government deficits can only be financed by foreign saving, private saving and “idle saving”. This he describes thus:

Idle savings. The only government spending that truly increases current purchasing is the amount that would have otherwise sat idle in safes and mattresses. Those are the only dollars not already circulating through the economy as consumption, or through the financial markets as investment spending.

Idle savings are rare. People and businesses generally invest or bank their savings, where the financial markets transfer them to other spenders. Banks that receive savings either lend them out to a spender, or (when afraid to loan) invest them conservatively to earn some interest. They are not hoarding customer deposits in massive vaults (beyond the required cash reserves).

This is an odd conflation of saving, measured as a flow, and financial assets. But lets take the equation at face value, there is an incredibly counterfactual observation that there no reserves are behing held in excess of required cash reserves. According to the St. Louis Fed, excess reserves are now approximately $1 trillion dollars. Well, no need for facts to get in the way of a good polemic.

Mr. Riedl’s main point is:

All government stimulus spending requires first borrowing dollars that would have otherwise been applied elsewhere in the economy. The only exception is money borrowed from “idle savings,” which for reasons described above likely constitute a minuscule portion of the $814 billion stimulus.

As I’ve mentioned here and elsewhere, this is true in a full employment model. (I’m working off of textbook models; move to coordination models, or allow monopolistic power, and you have lots of other inefficiencies arising).

Mr. Riedl concludes:

Economic growth requires raising worker productivity to create more goods and services. Government stimulus spending represents a naive “magic wand” attempt to create purchasing power and wealth out of thin air.

No wonder the unemployment rate remains high.

Well, if we’re in a Classical world, then there is no involuntary unemployment. If we’re in a New Classical world, then whatever involuntary unemployment exists is not systematic. If there is involuntary unemployment, then there are resources that are not being utilized, and putting them to use naturally raises productivity (remember labor productivity is defined as output per man hour).

Empirical Evidence on the Fiscal Multipliers (from Peer Reviewed Publications, not Heritage Foundation Issue Briefs)

Instead of polemics, or reasoning from accounting identities, I’m going to appeal to empirical evidence. From my entry in the New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics:

2.5 A Survey of Basic Results

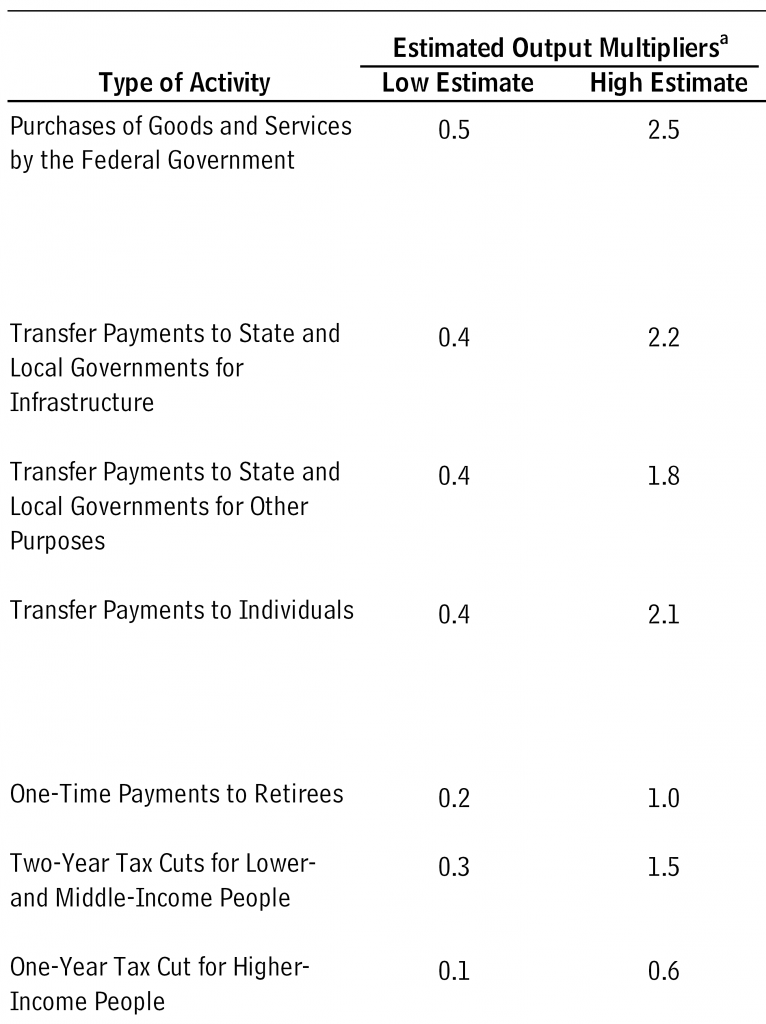

Obviously there is too voluminous a literature to review comprehensively. I focus first on the United States. CBO (2012a, Table 2) has provided a range of estimates the CBO considers plausible, based upon a variety of empirical and theoretical approaches.

Table 1: Ranges for U.S. Cumulative Output Multipliers. Source: CBO (2012a), Table 2.For goods and services, the range is 0.5 to 2.5; in line with demand side models, the cumulative multiplier for government spending on transfers to individuals are typically lower, and range from 0.4 to 2.1. Tax cuts for individuals have a multiplier of between 0.3 to 1.5, if aimed at households with a relatively high marginal propensity to consume.

When assessing whether a government spending multiplier is large or small, the value of unity is often taken as a threshold. From the demand side perspective, when the spending multipliers is greater than one, then the private components of GDP rise along with government spending on goods and services; less than one, and some private components of demand are crowded out. (Since transfers affect output indirectly through consumption, multipliers for government transfers to individuals should be smaller than multipliers for spending on goods and services.)

Reichling and Whalen (2012) discuss the range of multiplier estimates associated with various approaches. Ramey (2011a) also surveys the literature, and concludes spending multipliers range from 0.8 to 1.5. Romer (2011) cites a higher range of estimates, conditioned on those relevant to post-2008 conditions.

The above estimates pertain to the US. Obviously, one can expand the sample to other countries and other times. Van Brusselen (2009) and Spilimbergo et al. (2009) survey a variety of developed country multiplier estimates.

Almunia et al. (2010) find, using a variety of econometric methodologies, that fiscal multipliers during the interwar years are in excess of unity, when looking across countries. Barro and Redlick (2009) incorporate WWII data in their analysis of US multipliers; critics have noted that rationing during the WWII period makes questionable extrapolation of their results to peacetime conditions.

Lessons from Recent Fiscal Experiment: TCJA and BBA

Since 2010, we’ve accumulated some additional observations on fiscal policy efficacy, in the form of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and the Bipartisan Budget Agreement, both of which substantially increased fiscal stimulus, exactly at a time when the economy was arguably close to full employment.

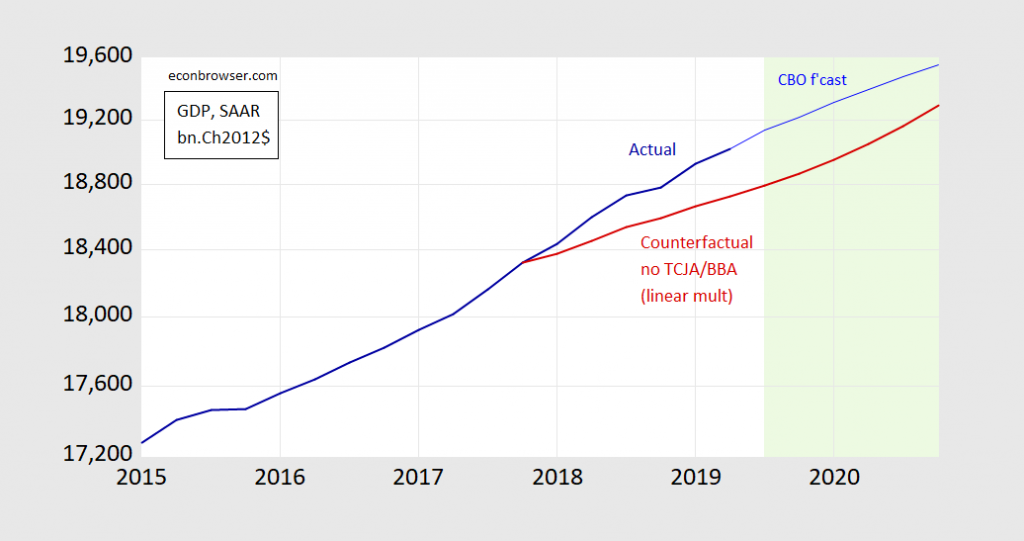

If multipliers are invariant to business cycle conditions, then conventional estimates suggests that in the absence of the fiscal stimulus, GDP growth would have decelerated. I show the counterfactual below, using estimated impacts from Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018).

Figure 1: Real GDP as reported (dark blue), GDP as implied by CBO Jan. 2019 forecasted growth (blue), and counterfactual GDP under no TCJA/BBA (red) with linear multipliers; annual output difference interpolated using quadratic fit. Light green is forecast period. Source: BEA, CBO (January 2019), and Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018), and author’s calculations.

This counterfactual seems implausible given the pre-TCJA/BBA trajectory of the economy. But perhaps this finding explains the mystery of the small impetus to GDP growth given by the Trump tax cut/spending increase. As noted in my survey:

5.1 State-dependent multipliers

The demand side interpretation of the multiplier relies upon the possibility that additional factors of production will be drawn into use as demand rises. If factors of production are constrained, or are relatively more constrained, as economic slack disappears, then one might entertain asymmetry in the multiplier.

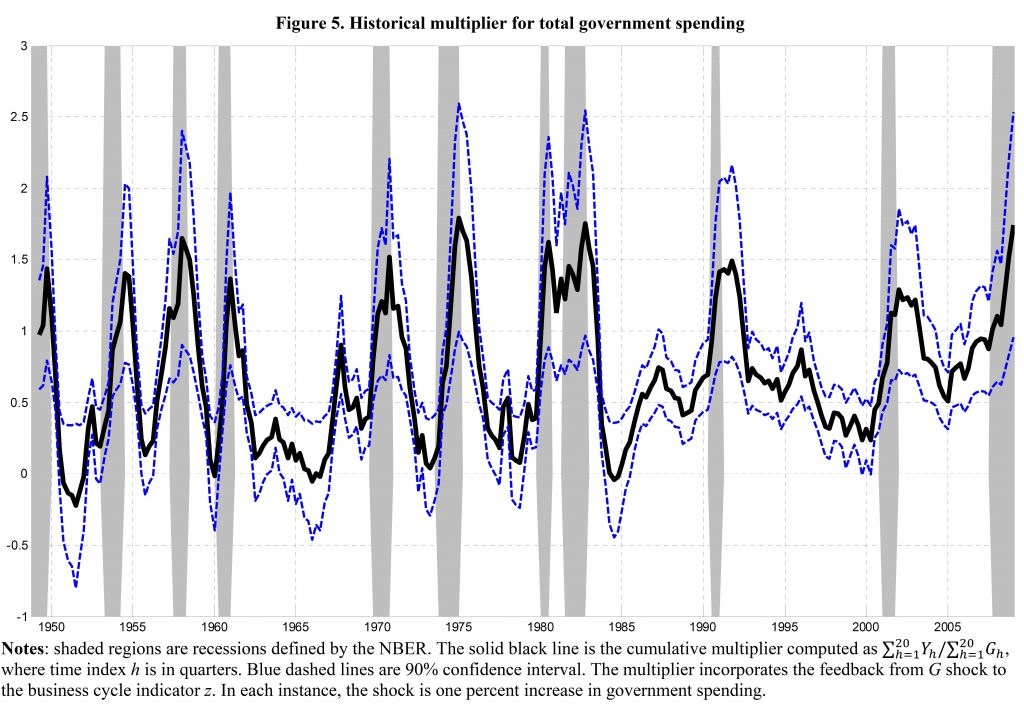

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012a,b) and Fazzari et al (2012) use VARs which allow the parameters to vary over expansions and contractions.[1] Baum et al. (2012) condition on the output gap. The common finding in these instances is that multipliers are substantially larger during recessions.

To highlight the variation in the multiplier for the US, I reproduce Figure 5 from Auerbach and Gorodnichenko’s (2012b), which plots their estimates of the multiplier over time.

A different perspective on why long term multipliers are larger during periods of slack is delivered by Delong and Summers (2012).[2] They argue that long periods of depressed output can itself affect potential GDP, following the analysis of Blanchard and Summers (1986). The prevalence of high rates of long term unemployed is one obvious channel by which hysteretic effects can be imparted. When combined with an accommodative monetary policy or liquidity trap, then the long term multiplier can be substantially larger than the impact multiplier.

Source: Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012b).

Hence, fiscal multipliers are largest exactly at times when expansionary fiscal policy is most needed. Estimates of multipliers based on averaging over periods of high and low activity are hence useful, but not necessarily always relevant to the policy debate at hand.

[1] Auerbach and Gorodnichenko use a smooth transition threshold where the threshold is selected a priori. Fazzari et al. estimate a discrete threshold.

[2] Quantification of long term impacts of depressed activity on potential GDP can be found in CBO (2012b).

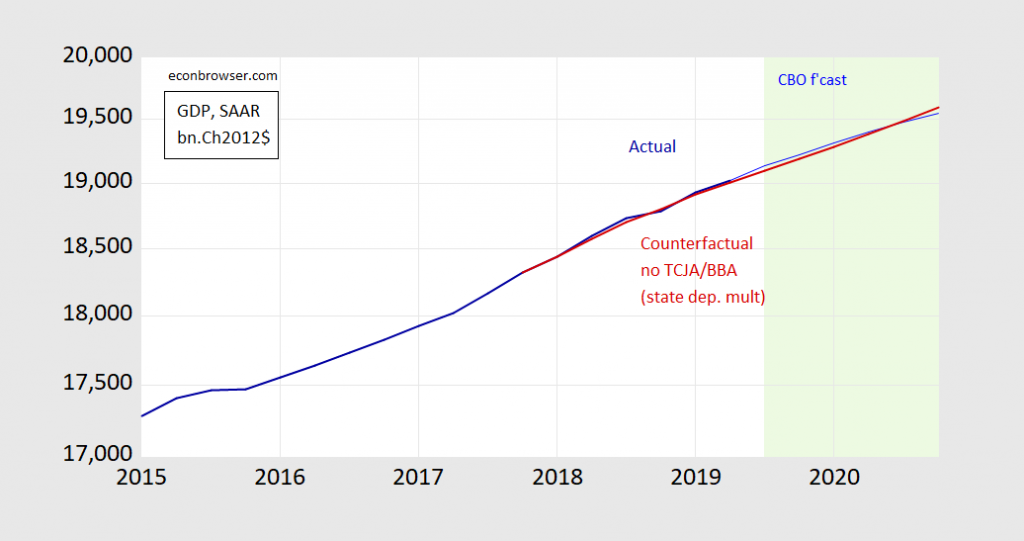

In other words, state dependent multipliers when near full employment are smaller. Using the estimates from Cohen-Setton and Gornostay, one finds that for the trillions of dollars worth of fiscal stimulus, we got precious little.

Figure 2: Real GDP as reported (dark blue), GDP as implied by CBO Jan. 2019 forecasted growth (blue), and counterfactual GDP under no TCJA/BBA with state dependent multipliers (red); annual output difference interpolated using quadratic fit. Light green is forecast period. Source: BEA, CBO (January 2019), and Cohen-Setton and Gornostay (2018), and author’s calculations.

Conclusion

Let’s hope we don’t go through the next recession debating in the same way whether fiscal policy can affect GDP, particularly during periods of economic slack and accommodative monetary policy (e.g., Fama, Mulligan, etc.).

Forgive me for once again being off topic, I have nothing insightful or constructive to add on this thread topic other than I am pro-fiscal policy under the right context, of which now probably qualifies as one of those contexts (or certainly by summer 2020 we would be at that point).

I saw this post on reddit literally seconds before popping in over here—it is spending/cost related and the numbers were crunched out on Rstudio by the reddit commenter (who is not me)

https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/cy6cow/can_you_spot_the_outlier_oc/ He also shows his data source link which is OECD.

I saw some interesting video on reddit related to HK that was quite fascinating. I find myself tempted to post it, but I think even for me this is stretching it, and encourage those are interested to wander on reddit.

Also off topic but I thought you might enjoy the irony:

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/tiffany-trump-instagram-post-respond-madeleine-westerhout?fbclid=IwAR3emUMeCSnjKQEWeG28SP-ZZB8C38u9yrYc2c8IoXnG9pFYfJ76eQEzgJ8

“Westerhout also reportedly told the journalists that Trump didn’t want to be photographed with Tiffany because he believed her to be too overweight.”

Maybe Tiffany isn’t a size 2 but lord her daddy looks like Jabba the Hut! But this gets better:

The youngest Trump daughter posted a poem by Rumi several days later, which read in part: “Study me as much as you like, you will never know me. For I differ a hundred ways from what you see me to be.”

Rumi is a 13th century Muslim scholar. Good for Tiffany to quote him and I bet daddy has no effing clue the author was a Muslim!

@ pgl

I don’t want to portray myself as a Tiffany fan, because I’m not. My guess is if I knew her on a personal level I would pretty much detest her. At the same time, my guess is of all of donald trump’s children she is the most well-balanced (although in this case we’re stretching the “well-balanced” term quite a bit). My personal experience on this (I don’t know what general wider research shows) is that often times the child who escapes the favoritism of the parents (she is obviously the black sheep in the group) is in essence “done a favor” as they get a taste of what real life is, with its obstacles and headwinds, and therefor better able to handle life’s real boxing blows over an extended period of time. So—in that sense, Tiffany should probably thank her father for being the _____ he is, as it’s probably made her a “better person” than she would otherwise be.

You’re right it is a fascination social dynamic to read about and watch—and let’s put it this way, I’m not joining the Tiffany fanclub anytime soon—but she has 30 times more my respect than Ivana or any of her siblings do.

We don’t know much about him and to their credit the Trumps keep him out of the spotlight, but based on limited public exposure Barron seems like a well adjusted kid.

Well done, Menzie, and looks familiar.

“Congress does not have a vault of money waiting to be distributed. Every dollar Congress injects into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed out of the economy. No new spending power is created. It is merely redistributed from one group of people to another. It is intuitive that government spending financed by taxes merely redistributes existing dollars. Yet spending financed by borrowing also redistributes existing dollars today. The fact that borrowed dollars (unlike taxes) will be repaid some years later does not change that.”

Riedl may be invoking Ricardian Equivalence (RE) but as been pointed out many times – lines like this show no understanding of the actual underlying model. RE may hold that cutting taxes today requires more taxes in the future and in a life cycle model, the fact that the present value of all future taxes has not change means no additional private consumption.

OK but suppose we finally decided to have some massive infrastructure investment in things like by subway system and other over do projects. We get an immediate and large increase in government purchases with the need to finance it over the long-term means a much more modest reduction in private consumption. Assuming Riedl gets even first grade arithmetic – might we suggest that he model out the net impact on aggregate demand today. It still is rather large. It sure ain’t zero.

“Last week, the Congressional Budget Office released a report claiming that the $814 billion “stimulus” has added 3.4 million net jobs. This surely comes as a surprise to the 3.5 million Americans who have lost their jobs and remained unemployed since the stimulus was enacted in February 2009.”

Wow – he is suggesting that ARRA caused this decline in employment?

Let’s check with FRED:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS

It seems employment had been a free fall since the beginning of 2008. Yea – employment did fall by an additional 3.5 million in the early years of the Obama Administration. Did Rield not get this was the entire point of ARRA? No one ever said the fiscal stimulus would reverse the free fall immediately. But this kind of dishonesty is what right wing economists excel at so why not lead a really dumb commentary with such a stupid statement.

In your summary, it is worth including the “welfare multipliers,” asking if the increase in G improves welfare. This is available in all NK models.

According to the St. Louis Fed, excess reserves are now approximately $1 trillion dollars.

Yes, today’s reserves are ~$1T, but Riedl was writing back in 2010 and even back then excess reserves were not far below $1T. In fact, the big spike (or “blip”?) in excess reserves happened in late 2008 when the Great Recession really started to take hold. In 2010 Riedl easily could have looked up how excess reserves had spiked from virtually zilch to almost $1T in a heartbeat.

I’m sure that in his head Riedl understands that GDP is a flow variable, but somehow when writing about fiscal multipliers he seems to have adopted the language and imagery of GDP as a stock variable. I guess it’s a case of cognitive dissonance. I see this a lot and it’s especially common among conservative economists. I dunno, maybe it’s related to the conservative mind’s tendency to see things statically. Flow variables are inherently dynamic and stock variables tend to be more static. You see this same kind of thinking with people who equate the macroeconomy with the household economy. In the household economy people view saving as wealth (e.g., quantity of money in the bank) and so they misapply that same understanding to the role of saving in the macroeconomy. In the household economy thrift makes sense in tough times, so people forget that one person’s saving is another person’s lost income. Riedl’s instinct is to imagine a kind of qualified First Law of Thermodynamics to macroeconomics in which the total amount of income in the system can never be created or destroyed by anything on the demand side. All creation and destruction comes from the supply side. So when people save, the total stock of saving in the system is forever preserved; and then through a qualified kind of Second Law of Thermodynamics that stock of saving is transformed into investment demand. Riedl’s macro universe never leaks savings out of the system. Intellectually he might know that saving and GDP are flow variables, but his unguarded intuition sees saving and GDP as stock variables.

“I’m sure that in his head Riedl understands that GDP is a flow variable, but somehow when writing about fiscal multipliers he seems to have adopted the language and imagery of GDP as a stock variable. I guess it’s a case of cognitive dissonance.”

Kudlow too was adding stock variables (monetary concepts) and flow variables (government budget deficit) back then. In Kudlow’s case, one cannot just assume he does get the difference. Then again – you never know. Kudlow often flat out lied to his National Review readers assuming that they were stupid enough to buy his ‘cognitive dissonance’ as you so politely put it.

I already left one reply and I imagine they are poling up. But here is another.

Most here, but maybe not all, especially the hard core Trumpists who do not know much econ, know and is implied in what Menzie has presented here involves the matter that fiscal multipliers are lower in periods of near full employment like we have been for the last several years. So Trump’s deficit-ballooning tax cut did not have much of a multiplier to it. He got a small and brief stimulus from it, but that is basically over, and now, with a possible recession looming, we have a massive budget deficit that will reduce the willingness of Congress and others to juice it up a lot more if a recession does arrive.

Of course if Trump loses and some poor Dem is in when the recession arrives, that will just be fine with GOPs in Congress, don’t let that Dem prez have any help in getting the economy back out of recession! This has been a now longrunning hypocrisy by them: we are the budget-balancers, except just the opposite when we are in power.

my father pointed something out to me many years ago. he was a democrat, but he was not tribal and partisan like we see today. but he clearly observed that most democratic presidents are elected into office to clean up the previous republicans mess. once the dirty work is done, the republicans would return and repeat the process. it was a way of keeping democrats from implementing their policies, because they carry enough responsibility to fix the problems first. republicans were trained to never admit failure, and the public implicitly understood this. which is why you rarely elected a republican president into poor conditions to begin with.

Let me echo your thoughts by noting a concept you recently brought up. Riedl seems to have never grasped what Keynes called the paradox of thift – a key issue when the economy is far from full employment. Trump and his minions likely think they can exploit the paradox of thift in a full employment. Keynes must be rolling over in his grave.

Barkley,

How about you or Professor Chinn writing some op. ed. pieces in the WSJ over the next couple years educating readers? Even if some folks have taken macro economics or even intermediate macro., knowledge fades as we age and put most of our energy into our job or profession.

Perhaps a version of this blog topic would be very well received. Unless someone is an economist or follows the subject quite closely, I wonder how many (or perhaps how few) WSJ readers or the general voting public are familiar with,

Table 1: Ranges for U.S. Cumulative Output Multipliers. Source: CBO (2012a), Table 2. above,

Figure 5, Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012b). or Figure 2, and

Figure 2.

Much energy seems to be spent counterproductively by the right attacking the left and by the left attacking the right. Perhaps educating WSJ readers an other voters may be transformative. I choose the WSJ since readers may lean somewhat conservatively and perhaps educating WSJ readers may result in “trickle down” in knowledge to other conservative leaning voters.

Hello AS,

Very good suggestions.

At work, all of my immediate supervisors have had a Ph.D. in a physical science. I am smart enough to know that I am not Ph.D. smart. But, over the 30+ years, I have really enjoyed watching those Ph.D.s go about their work.

Although almost all of the Econbrowser is above my level, I really enjoy Professor Chinn and guest articles posted on Econbrowser. I have especially enjoy Econbrowser in the current environment.

I’m just an ag technician, but I do take courses on edX to keep my skills up. I almost always sign up for the AP High School Physics 1 (algebra-based physics) course offered every year on edX by Professor Duffy at Boston U. I find the interactive graphs very useful in understanding the concepts in physics. There are also labs. High School students watch a lab video and build models to calculate the acceleration of gravity or coefficient of friction, etc…

I bring this–students in a MOOC (massive open online course) AP High School Physics 1 course building simple mathematical models–up to urge Principles of Econ instructors to include building simple econ models.

Way back, many years ago, when I was in school, I remember the instructor going through the course textbook. I never thought to go beyond the course textbook. But, through my work experience with those Ph.D.s, I learned that I can check those tables or update tables with new information. I learned that I can duplicate a simple graph in a peer-reviewed journal. So, I am suggesting that instructors go through an example of updating a table or graph that is not in the course textbook.

Back when I was in school, there was no internet. There was no way to easily get up-to-date data. But, today, it is incredible the amount of easily accessible current econ data available on the internet.

And last, I think some of my Ph.D. supervisors have some silly economic ideas. If you think only the uneducated masses have silly economic ideas, see how many Ph.D.s can pass the AP High School Micro/Macro Econ test. I checked the degree requirements at the University of Georgia (I was born and still live in Georgia). I have never attended UGA, but, from what I can tell, it seems to me that someone could get a Ph.D. without having taken a Principles of Econ course.

https://osas.franklin.uga.edu/franklin-college-social-sciences-other-history-requirement

As a life-long learner who has taken some MOOC econ courses, it is not too difficult for me to tell when some of my Ph.D.s in a physical science says something silly about economics. But, it takes Econbrowser to tell when a Ph.D. in economics says something silly about economics.

Much appreciate Econbrowser in this environment.

Cheers,

Frank

Countercyclical fiscal policy is only ineffective when the other party proposes it. Basically: dont spend money on your; constituents (but spend them on mine when I’m in charge).

So this time around I expect the Democrats and liberals to be telling me tax cuts bad, debt bad, don’t fund the military, etc. etc. Infrastructure bad (when its funded with public-private partnerships).

For the record, I am not sure I have any faith in the multipliers if we have a recession while unemployment is as low as it is. The reality is that the FOMC will offset fiscal policy (tax cuts or spending) to prevent inflation from going above 1.75%, same as it ever was.

“Countercyclical fiscal policy is only ineffective when the other party proposes it.” So true. Forgive but this reminds me of my favorite Reagan line – “tax& tax and spend& spend” which of course he replace with “spend&spend and borrow& borrow”!

@ pgl

One of your better comments.

https://www.amazon.com/gp/offer-listing/0679725695/ref=tmm_pap_used_olp_0?ie=UTF8&condition=used&qid=1567372834&sr=1-1

I feel certain the small numbers in this book will seem comical now—they were considered gargantuan at that time.

When I read such junk parading as economics, I have to check the author’s bio:

https://www.manhattan-institute.org/expert/brian-riedl

“Brian Riedl is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a member of MI’s Economics21, focusing on budget, tax, and economic policy. Previously, he worked for six years as chief economist to Senator Rob Portman (R-OH) and as staff director of the Senate Finance Subcommittee on Fiscal Responsibility and Economic Growth. He also served as a director of budget and spending policy for Marco Rubio’s presidential campaign and was the lead architect of the ten-year deficit-reduction plan for Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign .

During 2001–11, Riedl served as the Heritage Foundation’s lead research fellow on federal budget and spending policy. In that position, he helped lay the groundwork for Congress to cap soaring federal spending, rein in farm subsidies, and ban pork-barrel earmarks. Riedl’s writing and research have been featured in, among others, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and National Review; he is a frequent guest on NBC, CBS, PBS, CNN, FOX News, MSNBC, and C-SPAN.

Riedl holds a bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from the University of Wisconsin and a master’s degree in public affairs from Princeton University.”

OK – he worked for a bunch of GOP hacks and wrote for rags like the National Review. And of course his right wing nonsense fared well at Heritage. Not much of a resume it seems. But wait – he got an undergraduate degree from the University of Wisconsin? How on earth did that happen?

pgl,

Why are you (and others here) going on and on so much about Riedl? He is a nobody with near zero influence. Not worth mentioning more than once, and at that only briefly, a completely unimportant figure of no consequence.

Oh yeah. Just went back and see Menzie quoting Riedl up front to take him out with his Palgrave entry. I was mostly looking at that. Yes, Riedl has gotten some press and deserves to be taken out.

pgl,

UW long has had a conservative faction and strong Republican group, even if they are largely a small minority on that large campus. the ACU guy Keene (forget first name) came out of there, and do not forget Dick Cheney did too. There was for a long time an alternative conservative student paper, the Badger Herald, which for a fairly extended period was actually a better paper than the official Daily Cardinal. I think that group has long gotten some energy out of their feeling of being put upon by all those liberals around them there on campus and in Madison more generally.

Gotta love Riedl’s lame defense of the 2017 tax cut. He actually claimed it was a progressive tax cut?

https://www.nationalreview.com/2017/11/tax-reform-four-misleading-arguments/

But let’s compare two lines. Early on he writes:

“The goal of deficit-neutrality is shattered by the $2 trillion price tag over a decade (adjusted for gimmicks).”

But later on he writes:

“it is legitimate to oppose these tax cuts because they would expand the projected ten-year budget deficit from $10 trillion to $12 trillion. But overheated critics are portraying this $2 trillion cost as the difference between fiscal solvency and a deficit-induced collapse. In reality, deficits will continue rising steeply with or without these tax cuts.”

He starts with how deficit neutrality will be SHATTERED which likely got the attention of Team Trump who huffed and puffed at the political hacks who run the National Review so being a good boy Rield had to add this later line. I guess the earth is flat and the earth is round at the same time!

What happens when we take a deeper look at these candidates and get past the slogans and platitudes?? Of course some commenters, after exaggerating Kamala Harris’s chances in this race, saying she was “leading” over Biden after quoting a poorly conceptualized poll, would rather us not look at Kamala’s record. Those same commenters would probably prefer you not know about Cory Booker’s record as well.

Some candidates do a kind of smiley tap dance to get ahead in life. Cory Booker and Kamala Harris fall into this category. If you’re handsome and/or superficially attractive you can often peal off a certain “strip” or “lane” of unread white middle class liberals who think they are getting their “SJW” bonafides by voting for non-white candidates. They never stop to think about (or informally research) the corporatists that have funded these candidates and their actual/enacted policies.

https://newrepublic.com/article/153778/cory-booker-foot-soldier-betsy-devos

These same candidates often do poorly in the same demographic groups they assume to have already won over (blacks in this case). The largest portion or ratio of Cory Booker’s own allocation of votes will be white female voters (mark my words). You can come to your own conclusions how it works out that way.

These private school “voucher” outfits are destroying and dismantling America’s public education infrastructure. No worries….. If Cory Booker can make a dollar off of our children growing up illiterate and/or in decrepit poverty, Booker is all aboard that train:

https://oklahoman.com/article/5624287/epic-charter-schools-under-investigation-by-state-federal-law-enforcement

https://www.publicradiotulsa.org/post/feds-also-looking-charter-school-allegation

https://www.readfrontier.org/stories/in-wake-of-criminal-investigation-into-epic-charter-schools-lawmaker-has-questions-for-state-superintendent/

https://www.readfrontier.org/stories/seeking-to-add-hundreds-of-faculty-to-its-ranks-epic-charter-schools-obtained-personal-information-of-tens-of-thousands-of-oklahoma-public-school-teachers/

https://oklahomawatch.org/2019/07/16/search-warrant-alleges-embezzlement-use-of-ghost-students-by-epic-schools/

Don’t EVER move your family to the state of Oklahoma—unless you want your child at age 16 talking like he/she has an extra copy of chromosome 21.

Professor Chinn’s takedown of Riedl reminds me of George Carlin’s critique of reincarnation. In Riedl’s logical world, where there is no new money, we should still be trading big stone wheels and pretty pebbles. No additional money is possible, and it is impossible to create value that was not there before.

So far as I can tell, the value of innovation or stimulus or any other creation of an economic good is not dependent upon the ownership of its originator. Wingnut welfare recipients miss this fact. Even an outhouse economist like me can figure it out without arithmetic. It must be nice to get paid well to say stupid things. Most of us are busy attempting to make a positive contribution to the economy and would starve if we were as illconsidered as Riedl and his ilk.

On the 80th Anniversary of the Start of the Greatest Catastrophe in History:

“In 1930 the US, the largest purchaser of German industrial exports, put up tariff barriers to protect its own companies. German industrialists lost access to US markets and found credit almost impossible to obtain. Many industrial companies and factories either closed or shrank dramatically. By 1932 German industrial production was at 58% of its 1928 levels. The effect of this decline was spiralling unemployment. By the end of 1929 around 1.5 million Germans were out of work; within a year this figure had more than doubled. By early 1933 unemployment in Germany had reached a staggering six million.” https://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/great-depression/

German Chancellor Bruning increased taxes to reduce the budget deficit and then implemented wage cuts and spending reductions an attempt to lower prices. The unemployment rate averaged 28% in 1932. Hitler became chancellor of the government in January 1933.

“The Weimar government failed to muster an effective response to the Depression. The usual response to any recession is a sharp increase in government spending to stimulate the economy – but Heinrich Bruning, who became chancellor in March 1930, seemed to fear inflation and a budget deficit more than unemployment. Rather than ramping up spending, Bruning decided to increase taxes to reduce the budget deficit; he then implemented wage cuts and spending reductions, an attempt to lower prices. Bruning’s policies were rejected by the Reichstag – but the chancellor was backed by President Hindenburg, who in mid-1930 issued his policies as emergency decrees. Bruning’s measures failed and probably contributed to increased unemployment and public suffering in 1931-32. They also revived government instability and bickering between parties in the Reichstag.”

I bet his economic advisers belonged to the Brian Riedl school of macroeconomics!

We are not just discussing academic theories; we are discussing the fate of the world.

Economic policy mistakes have produced catastrophes on a massive scale.

We should be very serious about facts and history. We certainly don’t want to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Had Bruning wanted to act, inflation fears or not, he did not have the necessary fascist apparatus used by Hitler and Schacht.

Germany went in to the depression deep in debt (Versailles reparations, lost territory, led to hyperinflation) to a lot of countries, including the US. Some German debt was “called” as the lenders were on the ropes as well.

Germany was “out of credit” and did not learn to internalize debt instruments until MEFO bills (Hjalmar Schacht and political “motivation”) came out. These instruments required the kind of enforcement only available under Hitler.

The history I read is by Richard J Evans: The Coming of the Third Reich. He went through Versailles etc. and laid the harshness on Germany of the Depression on the inability to raise credit.

However, if you suspect history rhymes……. you may question the use of economic sanctions on places like Iran, and Syria.

“he did not have the necessary fascist apparatus used by Hitler and Schacht.”

Facist apparatus? This confirms it – you lost your mind a long time ago to either The Borg or some Russian programmer who turned you into his Bot.

pgl,

You could discover how Mussolini and Hitler ran their economies. “He” was Bruning who was not a fascist. You should read the history… Evans is quite well respected. There are many other resources on the macro problems Germany faced that added to the distress which the Nazi used.

German history is interesting. Bruning ran on classical economics and made things worse. He had no love of parliamentary democracy either.

Schleicher introduced the stimulus measures and Hitler merely continued that work. Germany reached full employment by 1936 and ‘over-employment by 1938.

IMHO Roosevelt could have achieved similar results if he had have had real wage decreases. not increases

I remember Adam Posen and someone else finding no evidence for ricardian equivalence in Japan in the 90s.

It is stil a theory in search of evidence.

Paul Evans and the AER thought they had evidence for Barro-Ricardian Equivalence:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1812704.pdf?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Do Large Deficits Produce High Interest Rates?

Paul Evans

The American Economic Review

Vol. 75, No. 1 (Mar., 1985), pp. 68-87

Published by: American Economic Association

This paper made a big splash in the day but let me tell you why it was always utter nonsense. Evans idea was to look at episodic events such as the 1981 tax cut, the WWII period, and the Civil War. Of course no one has reliable data on the Civil War and WWII was not a normal period. War rationing – hello?!

So let’s focus on the early 1980’s. Yes we had a massive fiscal stimulus and yet NOMINAL interest rates actually fell a wee bit. So Evans with just sheer ego in the amazing regression results he came up with suggested that anyone who doubted Barro-Ricardian Equivalence was a clueless fool.

But wait – what is the underlying theory he and Barro were pushing. Oh yea – people who save 100% of those tax cuts so no rise in consumption demand. But wait – consumption demand rose dramatically after the Reagan tax cuts. And we got crowding out of investment from the massive increase in REAL interest rates. I guess no one told Dr. Evans to factor in the rather large decline in expected inflation. And we also got massive dollar appreciation crowding out net exports. But Evans and his vaunted paper ignored all reality. And somehow the AER published this fairy tale?

The added wait to what Posen and his mate found was IF Ricardian Equivalence was to be found surely it would be Japan on the 90s.

Dear Folks,

I don’t know who to ask about this, maybe AS, or Barkley Rosser, or Menzie. But I am curious to why the argument that money is some sort of absolutely fixed stock, whose value can never be augmented by anything government does except for tax cuts, is not used to argue that all private investment is crowding out, too. If private investment is taking money that private investors would otherwise not use and creating items of real value, such as computers or golf balls or coal generation facilities, why isn’t government doing the same when it creates items such as bridges or weather satellites or roads?

Julian

“I am curious to why the argument that money is some sort of absolutely fixed stock, whose value can never be augmented by anything government does.”

Many theorists believe we are still on a quasi-gold standard and the money stock is actually fixed, i.e., if we create more dollars, the result will only be inflation.

Of course these theorists conveniently ignore the history since 1933 when FDR abandoned the gold standard. Since then, the M2 money stock has increased by

$14 trillion and yet inflation is at a historic low. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2NS

In fact, we have doubled the money stock since the Great Recession began and yet the inflation rate has been reduced by 35%. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BPCCRO1Q156NBEA

Julian,

That is a question for the experts. Above my paygrade.

Julian,

The standard story on crowding out is that it happens when economy near or at full employment. It is not that the stock of money is fixed, which can easily be varied by Fed policy. It is the limit on real resources. So there becomes a competition between public or private use of those resources, so if public use rises private use falls. If this competition is showing up in a conflict over borrowing for their respective activities, then traditionally interest rates rise.

You poke at a valid point that indeed generalliy gets ignored. If what is going on is a competition between private capital investment and public capital investment, then it is not given that the private is more productive as implied by the usual discussions of “criowding out,” that the awful public spending is crowding out the supposedly virtuous private spending. But many of us can easily think of comparisons where we would be likely to favor the public investment over the private, e.g. a new public school versus a new gambling casino in Las Vegas.

What about addressing the prevalence of narrow confidence intervals in the multiplier literature ? Or addressing the point that with optimal monetary policy, fiscal multipliers will be zero?

Jeff: Well, in my survey (link in post) (1) I cite among others Ilzezki et al. w/90% CI’s, (2) I stress importance of assumed monetary policy reaction function. I’ve never heard “optimal” monetary policy yielding 0 multipliers — full inflation targeting, yes — but it’s not clear that that is “optimal”, except in certain specific models. See:

https://www.nber.org/papers/w16479.pdf

http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~mchinn/Fiscal%20Multipliers.pdf

My question was more about whether or not studies with less than 90% CIs were impacting the range of estimates. I would also add that 90% CIs are still fairly generous. How many of those 90% CIs results become insignificant when you move to 95%?

And simply “stressing the importance” of assumed monetary policy just seems like a bit of lip service. The real question is how do the results of these studies change when you control for monetary response.

Jeff: Don’t know the answer to the first question — probably there’s a meta-analysis out there that addresses the issue. On the second, all DSGE and macroeconometric models have to take a stand on monetary policy in order to close the model. I doubt that the reaction function used — most are Taylor principle — would satisfy your definition of “optimal” monetary policy since that optimality is typically model-specific.

My question is not theoretical, it’s empirical. Put differently, how do you know that the empirical estimates of a “fiscal multiplier” are not just estimating the degree to which monetary policy was not sufficiently accommodative?

Jeff: Well, that’s what SVARs are all about…

Look, my general point was that none of this was controlled for in the empirical evidence sited in the post. We know from other studies that estimates of the fiscal multiplier are significantly impacted once you control for the fact that monetary policy will respond to changes in fiscal policy. For example, Ilzezki et al. actually find negative multipliers when monetary policy responds to fiscal policy. But none of this was presented in your “prebuttle” that fiscal policy can be effective. So what we are left with is a table of multipliers from the CBO and time series of multipliers from Auerbach and Gorodnichenko that don’t control for something so important that it could reverse the conclusions. And oh, by the way, the results may or may even not be significantly different from zero at the 95% level. Overall, if this is the best argument that can be made, it’s fairly weak evidence and following Bryan Caplan’s advice I’ll be lowering my belief that the proposition is true.

Jeff: Wow. Well, let’s just say my impression of the literature differs from yours. I’m sure I’ve addressed your question about CI’s and monetary policy somewhere in the dozens of posts I’ve written for Econbrowser on multipliers, if not in the survey.

Jeff: So a non-peer reviewed article by Dr. Murphy, who has not a single article in a mainstream peer-reviewed macro journal, is your go-to source?

“I’m sure I’ve addressed you question before.” Is that really your best reply? If so, I’m lowering my belief in the proposition even further.

Jeff: OK, I’ll write a post on it, amalgamating my previous posts, just for you. In the meantime, you haven’t addressed my concern that you are citing as authority a non-peer reviewed article by someone who’s never published in a mainstream macro journal. How do I spell “dubious”.

No need to rehash all of your same tired arguments, just looking for a post that adresses my specific points. Which by the way, do not hinge on the single Murphy article. So I’m not sure why you feel the need to focus on that. And if there is something in the Murphy paper you disagree with then discuss it but the Ad Hominem attacks don’t do anything to further your argument.

I look forward to that. Just be sure to specifically address my points. I would hate to see a re-hash of the same tired arguments. And nothing I’ve said hinges on the Murphy paper, so I’m not sure why you’re so fixated on that. But if you have specific concerns with the article, let’s discuss. Ad Hominem attacks don’t help your cause. Also, I wonder why you never bring up the lack of peer review with the macroadvisor multipliers you love to cite. How do you spell “hypocrite?”

Jeff: How often do I bring up Macroeconomic Advisers’ multipliers compared to Gali’s, Blanchard’s, or Auerbach-Gorodnichenko? I’m pretty sure I refer to MA’s forecasts/nowcasts a lot, but not the multipliers. They are different objects…

By the way, is it an ad hominem attack to say (1) an article is not peer reviewed, and/or (2) someone has never published in a mainstream macro journal. Both are inarguably true, both seem relevant. (After all, I never wrote the guy had never written in a Austrian journal or a Post-Keynesian journal, or an institutionalist journal…)

You are referencing the macroadvisor multipliers in this post, and now you’re trying to say you don’t reference them that much. That’s just laughable. And yes, I still say it’s an Ad Hominem to attack the author rather than critic the argument. So far I have heard nothing suggesting anything he wrote is incorrect. But nice try to deflect the conversation. If your best argument is to try and deflect the conversation towards the credentials of an author that is not even central to my point….well that speaks for itself.

Jeff: Try again. Macroeconomic Advisers doesn’t show up in the post; it shows up once in the Palgrave entry, and not in regards to multipliers, but structural models.

Re: the paper, I think the point is pretty obvious. I would say any semi-literate macro-economist would know when 68% or 95% confidence bands. If you think it’s a big insight, well, that says plenty about you. I would say more important is identification assumptions.

Look again. I think you need to do more homework.

Jeff: By the way, if I say my opthamologist has never studied neurology, and hence I’m a bit wary of him giving me a neurological exam — is that an ad hominem attack?

Still waiting to hear anything in article you think is incorrect. But kudos to you for trying to deflect the conversation away from the main points. You’re persistent if not persuasive.

Jeff: Nothing incorrect as far as I can tell; merely banal. Sorta like saying “hey the p-values are big! Nyah, nyah.”

I see. So first, the results couldn’t possibly be accurate because macro is so hard there’s no way a non-macroeconomost could get it right. And now the results are so obvious anyone could have pointed it out. If you’re going to find an excuse to reject an perspective just because it doesn’t fit your world view, I would think the least you could do is maintain a consistent story.

Jeff: I have no idea what you’re talking about; this is an incomprehensible comment.

Jeff: Here is what I think is a more insightful paper, albeit not peer-reviewed: http://www.euroframe.org/files/user_upload/euroframe/docs/2012/EUROF12_Gechert_Will.pdf

I’m pointing out that your knee jerk reaction is to assume opinions other than your are wrong. And when you can’t find a flaw you just dismiss them as “not important.” Your cognitive bias is showing.

Jeff: I don’t “assume” other’s opinions are wrong. I’m merely stating that the insights from nonspecialists (like if I ask my opthamologist for advice on my neurological symptoms) are likely to lead to either misapprehensions, or over-weight to really, really obvious points. All I can say is if I wrote an entire paper on how the use of the 1 std error prediction interval could lead one to mistaken overconfidence in IRFs, I sincerely doubt it would get published in a respectable journal.