Today we are fortunate to be able to present a guest contribution written by Mark Copelovitch (University of Wisconsin – Madison).

The COVID-19 crisis highlights the long-term consequences of past Eurozone policy mistakes. If the Euro is going to survive another crisis, now is the time for a comprehensive debt solution.

Eurozone countries are facing yet another crisis, as they struggle not only with the tragic public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also with the near-total sudden stop in the economy. The crisis, and the political debate over appropriate policy responses to it, have once again laid bare longstanding, fundamental problems in the Eurozone. The focus has rightly been on the immediate monetary and fiscal policy responses. But Eurozone countries’ ability to respond effectively to the crisis remain severely hampered by past policy errors that have left member-states – especially southern Eurozone countries – laden with debt and caught permanently in depression. Until and unless the Eurozone finally resolves these issues, the policy response to the Coronacrisis will almost certainly be insufficient, and the long-term prospects of the Eurozone will remain uncertain. It is long past time for the Eurozone to implement a comprehensive debt reduction plan that removes thirty years’ worth of debt overhang and creates the fiscal space for member-states to adequately respond to this and future crises.

A Europe-wide crisis in need of a Europe-wide response

COVID-19 has brought the Eurozone to a standstill. With economic activity crashing to a sudden stop, the need for rapid and massive monetary and fiscal policy intervention is clear. After an initial stumble, the ECB has stepped up. Last week, President Christine Lagarde embraced the “Draghi doctrine,” echoing former ECB President Mario Draghi and his famous 2012 line that “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.” In announcing the ECB’s plans to buy $750 billion of sovereign and corporate bonds to backstop Eurozone economies, Lagarde made clear that “There are no limits to our commitment to the euro. We are determined to use the full potential of our tools, within our mandate.”

This was welcome news. But the COVID-19 crisis also requires a joint response on fiscal policy. The problem, as Adam Tooze and Moritz Schularick noted last week, is that “no mechanism exists that allows the governments of the eurozone to respond jointly to such a shock. The result is that the policy reactions to the pandemic are so far overwhelmingly national.” The problem with primarily national responses, however, is that some Eurozone countries’ high debt levels and higher borrowing costs limit their capacity to respond aggressively with fiscal backstops. These differences are already starkly apparent, as comparisons between Germany and Italy’s fiscal rescue packages make clear. This is a recipe for both public health and economic disaster.

So what are the available options? The best and most effective would be Eurobonds. This is why more than 300 scholars of the European Union (including me) signed an open letter, published last week in the Financial Times, urging European leaders to “mutualize the fiscal costs of fighting this crisis” by issuing a common European debt instrument. Unfortunately, we have already seen sharp political opposition to this from the so-called “frugal four” countries (Germany, Netherlands, Austria, Finland) on the predictable grounds that this would create moral hazard and punish those countries that had responsibly saved for a rainy day.

A second, though far inferior option would be to use the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) to provide loans to individual countries in need. But the problem with this is obvious: it makes little sense for dealing with a common European shock for which no individual country is responsible. Moreover, ESM loans would only be used by countries with less fiscal room to maneuver, thereby carrying a similar stigma as previous IMF/Troika loans in the last Euro crisis. ESM chief Klaus Regling has downplayed these concerns, claiming that any such loans would have “very limited conditions.” But even limited conditionality would inevitably be politicized and end up diverting resources toward structural reforms and austerity in the midst of the mother of all liquidity crises. Consequently, it remains highly uncertain that Eurozone member-states would take advantage of any such ESM facilities in sufficient quantity to address the current problem.

Beyond these two options, smart scholars have now tabled a number of thoughtful proposals for further EU-wide fiscal initiatives. But all of these ideas are temporary and COVID-specific. They do little to address the deeper, underlying fiscal problem in the Eurozone: persistent, unsustainable debt overhang that has led to permanent austerity and stagnation in the southern Eurozone and transforms each new economic crisis into an existential challenge for the monetary union. These problems existed before the COVID-19 crisis, and they will persist long afterward without reform. Indeed, the fiscal problems of Eurozone countries today are the cumulative result of policy errors made both at the Euro’s founding and in the Euro crisis from 2010 onward. These errors have left Greece, Italy, and others laden with unsustainable debt. Failure to address this debt overhang problem, once and for all, threatens not only the ability to deal effectively with the immediate COVID-19 crisis, but also the longer-term future of the Eurozone.

The pre-Eurozone era debt problems never ended

The Eurozone’s first mistake – its “original sin” – is that several countries were allowed to join the monetary union in the 1990s despite obviously failing to meet the debt-to-GDP requirement the Maastricht convergence criteria, which stated that “public debt must not exceed 60% of GDP, unless the ratio is sufficiently diminishing and approaching the reference value at a satisfactory pace.” In the run-up to 1999, it was clear to everyone that Italy, Greece, and Belgium simply did not meet this criterion; none of these countries were remotely close to having debt levels in line with the other Eurozone countries, nor were they on trajectories to do so anytime in the foreseeable future. Thus, while relaxing the Maastricht criteria was surely good European politics – allowing all interested member-states to join the Euro at the outset, including all of the “Original Six” founders of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 – it also created massive legacy debt problems that have proven to be crippling for countries that permanently sacrificed monetary and exchange rate policy autonomy once they adopted the single currency.

SOURCE: De Grauwe 2009

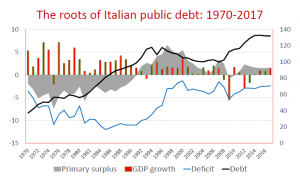

SOURCE: Larchinese 2020

This legacy debt problem is most clearly visible in Italy. Indeed, Italy’s current debt problems are due almost entirely to its pre-Euro debt overhang, which has hung like the Sword of Damocles over Italian policymakers for decades. At about 130%, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio today is only slightly higher than it was in the mid-1990s. Measured by its primary budget surplus, Italy has been more fiscally prudent than even Germany since the establishment of the Euro two decades ago. Yet two decades of austerity never brought Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio below 100%, leaving it now still facing the problem of lacking fiscal space to address a major economic crisis. The problems of ignoring the Maastricht criteria are still coming home to roost in 2020.

The last Eurozone crisis never ended

This legacy debt overhang has combined with the Eurozone’s second mistake: the failure to bring the last crisis to an end. Despite claims from European leaders that the Eurozone crisis has ended, the economic realities on the ground in the Southern EMU countries make it clear this is simply not the case. The level of economic devastation in Greece remains truly staggering. The country is now mired in a depression longer and deeper than the Great Depression itself, with GDP still more than 20% below 2007 levels, and a return to pre-crisis levels not in sight for years, if not decades. Beyond Greece, overall unemployment remains high throughout the southern Eurozone, with youth unemployment nearly 30% in Italy and higher in Spain and Greece.

Likewise, ECB monetary policy has never “normalized,” in the sense that the ECB has undershot its inflation target for nearly a decade. These two issues are, of course, related. It has been all but impossible for Spain, Greece, and Italy to adjust through internal devaluation and austerity while Eurozone monetary policy has remained targeted to the economic situation in Germany and the Netherlands rather than the Eurozone as a whole. In any case, the cumulative failure of the ECB to meet its inflation target means that price levels in the Eurozone are now about 10% below what they would be based on target projections. This has prolonged Eurozone stagnation and severely hampered the southern states’ ability to fully recover from the last crisis.

SOURCE: ECB

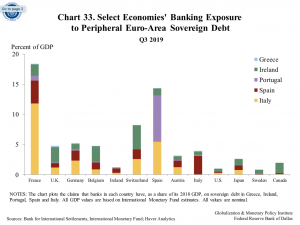

Beyond this, of course, the policy response to the Eurozone crisis failed to address the underlying institutional gaps and macroeconomic imbalances in the monetary union. In particular, banking union has not broken the sovereign-bank “doom loop.” Instead, the web of interlocking bank exposure to Eurozone sovereign debt remains thickly intertwined: French banks remain highly exposed to Italian and Spanish debt. Spanish and Italian banks remain highly exposed to each other’s sovereign debt, while Spanish banks remain highly exposed to Portuguese sovereign debt.

Furthermore, as we are now seeing with the rancorous debate over Eurobonds, neither the establishment of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) nor the ECB’s massive asset purchasing programs have addressed the fundamental macroeconomic and debt imbalances in the Eurozone. Instead, as last week’s row between the Dutch and Portuguese governments over “solidarity” and Eurobonds illustrated, too many Eurozone leaders remain beholden to the unhelpful narrative of “Northern Saints” and “Southern Sinners,” in which debt is always equated completely with bad policies and never ascribed to structural problems of monetary union.

If not Eurobonds, then comprehensive debt relief

In short, the Eurozone entered this latest crisis without having resolved either the debt and macroeconomic imbalance problems that existed in 1999, or the ones that have festered since 2010. It has chosen not to pursue the deeper political and fiscal integration that would solidify the monetary union, and the emerging disagreements over Eurobonds strongly suggest that the political support for any such deeper integration and reform still does not exist.

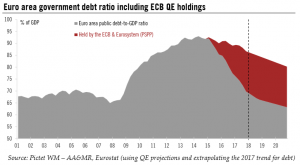

A more feasible solution is for the Eurozone to finally adopt a comprehensive debt reduction plan, along the lines of the Brady Plan adopted in 1989 to end the Latin American debt crisis. A Eurozone Brady Plan would be far easier to implement than the original, since the ECB and Eurogroup now hold half of all Eurozone sovereign debt themselves. The mechanics of this also would not be particularly complicated. Indeed, viable proposals have circulated for quite a while now. Countries could offer new bonds, involving both very long-term maturity extension and substantial principal reduction. The ECB and Eurogroup could take larger haircuts than private creditors. The debt relief provided by such a plan could provide all Eurozone countries – but most especially Italy and Greece – with substantial fiscal policy breathing space to address the COVID-19 crisis, as well as future crises. In addition, it would help end the debt-deflation spiral in the Eurozone and unwind the sovereign-bank doom loop that persists a decade after the Eurozone crisis began. In this environment, the need for Eurobonds or country-specific conditional ESM loans would be substantially diminished, if not eliminated.

Undoubtedly, critics of comprehensive Eurozone debt relief will reply that debt reduction will fuel moral hazard and that Italy and Greece’s problems require deeper structural reforms that debt relief will not address. To the first concern, the best reply still remains the one Ricardo Hausmann offered in the wake of the Asian financial crisis two decades ago: moral hazard simply is not the fundamental problem in financial crises and “other distortions are more binding.” One can respond similarly to the second concern. Yes, of course, structural reform is needed. But two decades of austerity and pretending that debt overhangs are sustainable has also not led to meaningful structural reform. Postponing long overdue debt reduction because of the specter of moral hazard or because there is more work to do on structural reforms is simply not a compelling argument. If anything, leaving southern European countries mired in depression with massive debt overhangs is likely to postpone serious structural reform of their economies for far longer.

Critics will also claim that Europe cannot afford debt relief, arguing that Italy, in particular, is “too big to fail, but too big to save.” It is key to recognize that the former is an economic assessment but the latter entirely political. The ECB and the Eurogroup collectively face essentially no resource constraint: the ECB issues the world’s #2 reserve currency and inflation is negligible. Many of the Euro-19 can borrow, both in the short- and long-term, at negative real interest rates, in essentially unlimited quantities. Perhaps comprehensive debt reduction would generate modest inflation in the Eurozone for the next decade. But this would actually be a welcome outcome that would finally enable the ECB to hit its inflation target consistently. As with Eurobonds, the only opposition to real solutions, then, is political.

If not now, when?

In sum, if the Eurozone is to be sustainable in the long run – and members are to have the fiscal space to respond to periodic crises such as the current one – then debt relief to create the necessary fiscal space may be the only politically viable solution. Again, deeper fiscal integration in the medium term, and a Coronabond issue in the short term, are the first-best policy options. But if this is not to be, given political realities, then a Eurozone Brady Plan is the next best option. And even if COVID-specific Eurobonds or other initiatives do become a reality, debt relief is still necessary to address the legacy debt overhangs in Greece, Italy, and elsewhere, and to facilitate long-term growth and on-target inflation in the Eurozone in the years ahead.

Now is the time for bold and creative initiatives to finally address the Eurozone’s persistent gaps and policy mistakes. Simply maintaining the current status quo – with its half-hearted fiscal solidarity and permanent fiscal austerity for southern European countries – will eventually lead to the Eurozone’s demise. The Euro has survived for two decades, in spite of its original sin and the policy errors of the last crisis. Some have taken this as evidence that those worrying about the Euro’s collapse over the last decade have been overly pessimistic. Yet as Herb Stein famously noted in regard to the US balance of payments deficit in the 1980s, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” European leaders should seize the momentum for action provided by the pandemic crisis to finally, at long last, address the debt problems that threaten the single currency’s long-term survival.

This post written by Mark Copelovitch.

Dissolve the Eurozone. The same countries that are basically opposed to Eurobonds can sponsor pro-Democracy candidates in Spain and Italy (much the same way that Russia tries to influence external politics in other nations). Junk something that has shown for the umpteenth time it doesn’t work, and follow the Brexit voters in exhibiting you actually do have a brain. That or bash your head into a brick wall for the 9,999th time so people like Christine “Tapie Arbitration Gift” Lagarde and Jean Claude Junkbrains can make 6 figure salaries on a permanent vacation. I pretty much don’t care anymore.

What do most large TBTF banks do for small businesses after the U.S. Federal government offers them multiple “bailouts” they often do not need or deserve?? Well, ask a leader at the Small Business Administration that question, and they may give you the honest answer:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/08/video-sba-official-blasts-big-banks-over-failure-quickly-distribute-loans/

Large banks mainly deserve to FAIL for taking excessive risks with depositors’ money. But letting large TBTF banks fail doesn’t give guys like Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke praise from those in the upper wealth echelons of society. Only Republican legislators saying “NO!!!” to the common man getting a mortgage “cram down” and “NO!!!!” to an adjusting of mortgage contract terms for the newly unemployed during a severe recession are worthy to be mentioned in the same high regard as a Hank Paulson or Ben Bernanke. I guess if you’re a little slow in the head, you keep offering banks money and see if for the 20th time in-a-row they decide not to pass those dollars on to the general public and see if the result is the same as it is every other time you’ve done it. So let’s give Italian banks and Spanish banks a bunch of money and watch what happens. I can’t imagine ANYTHING bad will happen, can you?? Let’s just make certain “the right” broker/dealers get “their share of the take” (commission) on those bond sales and purchases, ok?? We have to have our priorities here. We wouldn’t want large banks to “feel left out” by not making dealer commissions off of passing around the latest round of central banker “Monopoly” boardgame money, would we??