Today we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Robert Dekle, Professor of Economics at USC.

”Let us remember that the automatic machine is the precise economic equivalent of slave labor. Any labor which competes with slave labor must accept the economic consequences of slave labor.” — Norbert Weiner

In many countries, there is much handwringing about how robots will replace labor. In countries such as the U.S., China, and Germany, there is widespread fear that the adoption of robots will lead to technological unemployment, as humans are replaced by machines.

Japan, however, remains an exception. In Japan, public opinion is such that robots are less of a threat to jobs and more about economic survival, as the nation suffers from a chronic labor shortage. The country is striving to become the nation substituting the greatest number of jobs with robots.

In my recent work, I showed that this sanguine view about robots and jobs is justified. I found using Japanese data that a rise in robot intensity (robots per 1000 workers) rather than lowering the demand for labor, sharply increased the demand for labor in Japan.

This is in stark contrast to what researchers found for the effects of robots on labor demand in the U.S. and in Germany. Acemoglu and Restrepo find that an increase in robot intensity lowered the overall demand for labor in the U.S. Dauth, et. al. find insignificant effects of robot intensity on labor demand in Germany.

Japan is the ideal laboratory to study the effects of robots on labor demand. While in other countries, robots data start from the mid-1990s, in Japan, robots data run from the late 1970s until today, allowing me to examine the impact of robots on employment over a long span of time, not possible in other economies. One would expect the effects of robots will unfold over decades, instead of the 10 year span examined in the U.S. and in Europe in previous studies.

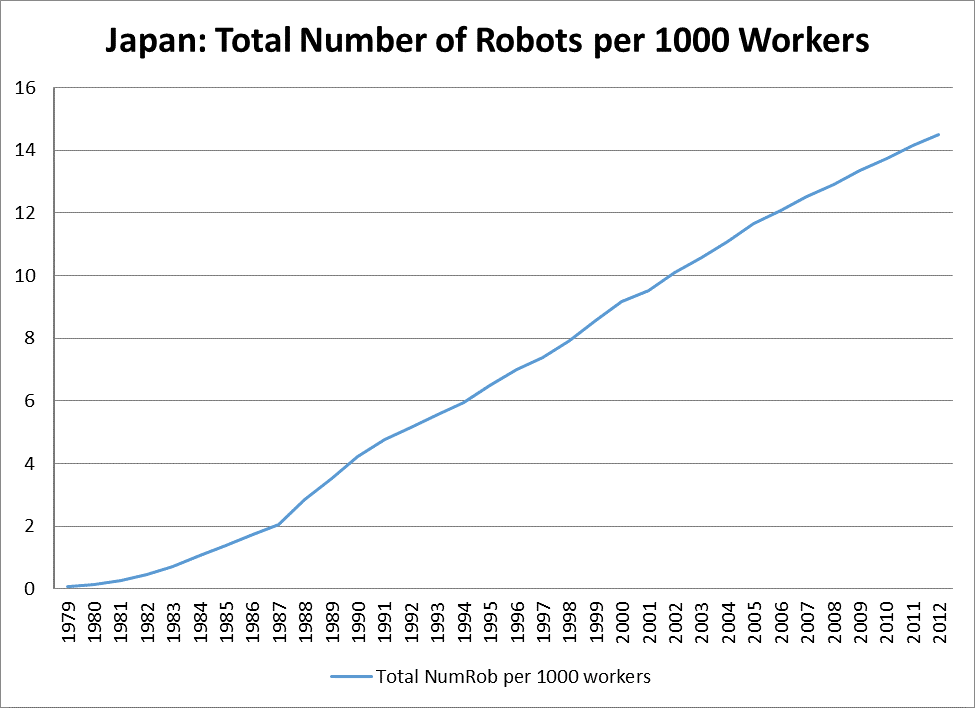

The chart below shows the growth in the aggregate robot intensity in Japan (robots per 1000 workers) from 1979 to 2012. Overall, there was a 15 fold increase in robots per 1000 workers in Japan during this period. Japan is also much more intense in the use of robots than the U.S. or Europe. Japan in 2012 had about 10 and 5 times as many robots as the U.S. and Europe. The intensity of robots in particular is pronounced in the automobile and electronics industries.

I separate the aggregate impact of robots on labor demand into three distinct effects: 1) the negative displacement effect; which is the substitution of robots into labor at the industry level; 2) the positive “productivity” effect, which is the increased demand for labor in that industry, owing to the decline in costs. 3) The third positive “macroeconomic effect” arises when the productivity increase induced reduction in costs raises total output, which increases demand in all industries.

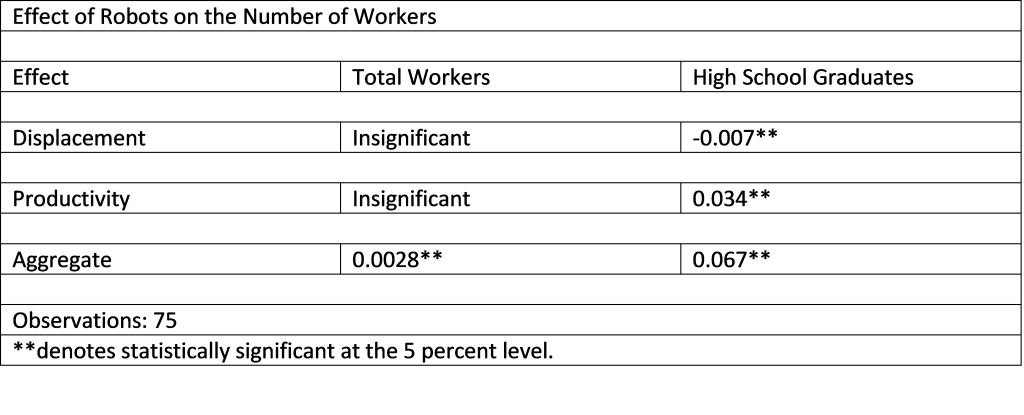

The Table shows estimates of the three effects on two categories of workers, Total workers and High School graduates (using ordinary least squares; the results were robust to the use of instrumental variables).

The results show that for the Total number of workers, the Displacement and the Productivity effects are statistically insignificant. The aggregate effect is highly significant. From these numbers, we can calculate that the 15 fold increase in robot intensity from 1979 to 2012 raised total employment by about 1/2 percent. For high school graduates, the increase in robots raised their numbers by 1 1/2 percent. These magnitudes are fairly large. For example, according to my estimates, they more than offset the negative effect of Chinese imports on Japanese total employment.

Why is the impact of robots on employment positive for Japan, but negative for the U.S.? In the U.S., the positive productivity effects of introducing robots is too small to offset the negative displacement effects. The history of using robots in the U.S. appears to be simply too short for the U.S. to actually experience the significant productivity gains so that the non-roboticized jobs can expand.

Since the late 1970s, Japan has been hit by various shocks that have collectively lowered employment. These negative shocks, which are not independent of each other, include the offshoring of Japanese production, imports from a rising China, the high yen, and the aging of the population. The employment-population ratio has fallen from about 65 percent in the 1970s to below 55 percent today.

I show that overall, robots have helped offset these negative shocks that have ravaged the Japanese economy. Robots have raised the productivity of Japanese industries, helped lower costs, raised average industry wages, and helped sustain the global market shares of Japanese corporations. This has allowed aggregate demand for Japanese labor to be higher than otherwise.

This post written by Robert Dekle.

So I’m wondering if Japan doesn’t see robots as an alternative to immigration. Could that be why Japan is more receptive to robots as a solution to its aging population problem?

That is an interesting observation, and one that had not occurred to me. Another analogy is the accelerated use of mechanical devices in the US early on, due to the lack of serf populations that were a part of European society more than a century ago.

Ultimately, the use of robots raises labor productivity and makes for a competitive advantage. Being a luddite won’t save your job.

Slugs, You might find this article by Noah interesting: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-08-28/shinzo-abe-s-legacy-in-japan-goes-far-beyond-abenomics

and this one: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-09-02/taxing-robots-won-t-help-workers-or-create-jobs

How can Japan have a shortage of labor if their employment to population ratio is only 55%? It sounds like there are plenty of available workers who just aren’t working for one reason or another.

I assume that the employment to population ratio you cited is the standard of OECD to count working age 18 to 64 year olds.

“How can Japan have a shortage of labor if their employment to population ratio is only 55%? It sounds like there are plenty of available workers who just aren’t working for one reason or another.

I assume that the employment to population ratio you cited is the standard of OECD to count working age 18 to 64 year olds.”

If EPOP is for the 18-64, 55% is really low. But if it is for the overall adult population, remember Japan has a rather elderly population.

FRED to the rescue:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LREM64TTJPM156S

Employment Rate: Aged 15-64: All Persons for Japan (LREM64TTJPM156S)

Before the pandemic it was over 78%. It is around 77% now. It seems they are doing a bit better than we are.

joseph I’m pretty sure that he is referring to the labor force as a percentage of the total population. According to OECD data for 2018 (complete 2019 data isn’t available yet), Japan’s labor force is 68.3M and total population is 126.4M, which is ~54%. The working age population 15-64 is 75.4M, so labor force to working age population is 90.6%. Actual employment is 67.2M.

Just saying, if one claims that there is a shortage of labor, then prove it. Usually “a shortage of labor” is just employers moaning, as always, that they just can’t get the cheap labor they want. Are wages rising sharply? If not, there’s no shortage of labor. Are people working for Uber? That indicates that there is a shortage of productive jobs, not a shortage of labor.

It seems the use of the term “robots” obfuscates the reality that “mechanization” has been a dominant factor in production for at least a century. The main difference is that “robots” are programmed and the labor associated with them is either maintenance or input/output of material handling. Just compare the history of automotive manufacturing at its earliest days to present manufacturing. The highly repetitive manual labor has been replaced by programmed machinery, but there is still a need for humans; the tasks are simply different and the numbers employed are fewer. And even when the “human touch” is still required, those workers are often augmented by equipment such as exoskeletons for workers lifting or reaching with heavy objects.

The same thing happened over the last century in agriculture. One farmer can operate a thousand acres where dozens of farmers were needed for the same production. Farmers now use computer programs to determine planting patterns and management. Combine technology almost makes the operator an observer.

Unlike Japan, the U.S. has a growing population so employment patterns are significantly affected by mechanization/robotization. Labor has shifted from production to service. The demand has shifted from menial to sophisticated. Your highschool diploma no longer guarantees much of anything except that you may be part of that sought-after “cheap labor” for businesses that have not or cannot yet be mechanized. But watch out, even those McDonald’s jobs may be a thing of the past.

We may have to redefine “social injustice” as stopping education at the highschool level. Time to expand community colleges. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nancyleesanchez/2019/10/24/community-colleges-and-the-future-of-workforce-development/#94a0495681f9