A wild ride for futures means…

Source: barchart.com, accessed 22 June 21.

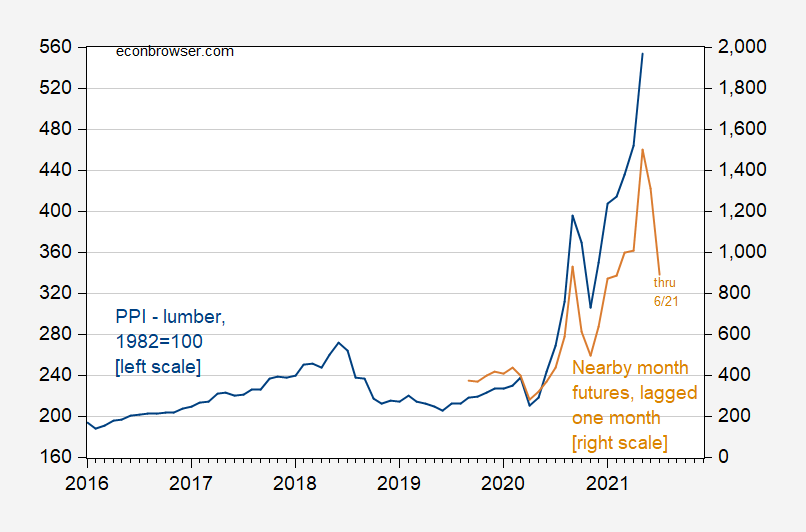

Do lumber prices (as measured by the PPI) move as predicted by the nearby month futures? Here’s a plot.

Figure 1: PPI for lumber and softwood (blue, left scale), and nearby month futures, lagged one month (brown, right scale). Source: BLS via FRED, and ino.com.

A one percent futures basis does not necessarily imply a one percent decline in lumber prices (as would be implied in a risk-neutral efficient markets setting). Mehrotra and Carter (2017) find that over the 1995-2013 period, at two months horizon, a one percentage point basis implies a 0.55 percentage point decline. If spot and futures prices move in tandem, this implies about a 7% decline in the June PPI, and around 20% decline in the July, bringing the lumber PPI back to around where it was in April.

At least, that’s what the futures are signalling.

I like how one can take Lumber Jul ’21 (LSN21) back to 1970. Nominal prices of lumber were not much higher in 2019 than they were in 1970. Maybe someone could provide an inflation adjusted series of historical lumber prices.

I think it’s fairly obvious that current lumber prices are one of those strange outliers that occur now and then with commodities.

While historically, the range has been fairly wide, between approx. $130 to $450 per thousand board feet, what has happened can be described as a 3 sigma event.

Very exciting over at the CME, and a groaner for contractors looking to build right now, but otherwise mostly irrelevant for long-term analysis.

Now, considering what effect climate change will have on lumber supply over the next decades, and at what price does the substitution effect occur…

we have large scale developers building large numbers of homes in developments over a very short period of time. not sure if this same environment existed 20 years ago. any insight on how this concentrated group of builders with large numbers of homes is contributing to such a spike? smaller developers can sometimes let a development sit for 6 months or a year if they hit a bump. can these big time developers do the same thing? or are they forced to buy simply due to scale and inability to “pause” for cheaper conditions? it also appears at this point, some developers have been able to push these costs onto the consumer, due to lack of housing supply in general.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/21/opinion/inflation-economy-biden-fed.html

June 21, 2021

The Week Inflation Panic Died

By Paul Krugman

Remember when everyone was panicking about inflation, warning ominously about 1970s-type stagflation? OK, many people are still saying such things, some because that’s what they always say, some because that’s what they say when there’s a Democratic president, some because they’re extrapolating from the big price increases that took place in the first five months of this year.

But for those paying closer attention to the flow of new information, inflation panic is, you know, so last week.

Seriously, both recent data and recent statements from the Federal Reserve have, well, deflated the case for a sustained outbreak of inflation. For that case has always depended on asserting that the Fed is either intellectually or morally deficient (or both). That is, to panic over inflation, you had to believe either that the Fed’s model of how inflation works is all wrong or that the Fed would lack the political courage to cool off the economy if it were to become dangerously overheated.

Both beliefs have now lost most of whatever credibility they may have had.

Let’s start with the theory of inflation….

https://static.nytimes.com/email-content/PK_sample.html

June 22, 2021

Will the tyranny of the 1970s ever end?

By Paul Krugman

Leisure suits went out of fashion more than 40 years ago. High inflation stopped being a problem only a few years later. Yet while you rarely see warnings about the imminent return of disco style, hardly a year goes by without dire predictions that ’70s-type stagflation is coming back.

Today’s column is about how the case for fearing runaway inflation has collapsed over the past few weeks. But I didn’t have space to talk about why such fears have received widespread publicity, even though they were always on very shaky ground.

Of course, one reason people are talking about inflation is that some prices have shot up in the past few months. But I don’t have the sense that inflation worriers are really arguing that soaring prices of used cars and lumber are harbingers of a return to double-digit inflation. Instead, they’re treating the background of price hikes as a kind of Greek chorus to reinforce their claim that we’re repeating the mistakes of the 1970s.

The question is why invoking the specter of the 1970s evokes such terror.

Not that the ’70s were a good time economically. The great post World War II boom ended circa 1973, introducing a long period of sluggish gains and often declines in median income. But the ’70s don’t stand out as worse in that respect than several other periods. Real income growth under Jimmy Carter was better than it was under George Bush the elder; the Gerald Ford and Carter era as a whole was better than the reign of George Bush the younger. And none of the economic travails of the period matched the suffering of the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath.

True, there was that inflation, although incomes by and large kept up. Still, by the numbers, it’s hard to see why we still scare children by telling them that if they’re bad, they’ll end up back in the 1970s. What’s all that about?

Part of the answer is that the economic troubles of the ’70s came along with other bad news. Crime was still on the rise; inner cities were decaying; we lost the war in Vietnam. These were pretty much entirely separate stories both from one another and from the economic malaise, but they tend to merge in historical memory.

But here’s the thing about historical memory: It tends to be selective, and what gets remembered often reflects elite agendas. To take an infinitely more important subject than mere economics, how many white Americans were ever taught about the 1921 Tulsa massacre? I know I wasn’t.

And so it is with economic history. You very rarely hear about the bleak economic mood of the early 1990s, a time of falling incomes, deindustrialization and widespread fear that the United States was losing out to foreign competitors. Somehow that episode got dropped from the curriculum even though Bill Clinton got elected by campaigning against the Bush economy.

But harping on the troubles of the 1970s serves a political purpose. To this day, I keep reading declarations that Carter-era stagflation is an object lesson in the terrible things that happen if taxes and spending are too high….

Well, heck, now Biden can continue to play to the Trumpist nationalist base, not to mention the Econbrowser house protectionists, and keep those lumber tariffs in place! Great!

Real median family income generally stagnated during the 1970s while real per capital GDP rose 2% per year despite inflation.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEFAINUSA672N

When the corporate media starts whining about that time period, you’re sure to smell a rat if you sniff a bit, just as you should any time the corporate media starts evoking the plight of the worker, or when they push policies because they supposedly benefit workers.

Heck that UK media rarely mentions the decline in UK real wages which was huge during the Cameron years. Of course someone posing under your name kept telling EV readers how real wages rose under Cameron.

I was what caused your latest rant when I saw ltr (anne) had referenced an oped in the NYTimes by Paul Krugman which included this:

‘Not that the ’70s were a good time economically. The great post World War II boom ended circa 1973, introducing a long period of sluggish gains and often declines in median income.’

I guess this does not count as his hair was not on fire.

JohnH,

A fact connected to the appearance of the disjuncture between median and mean real per capita incomes in the 1970s is that this was the point where US income distribution reached it greatest level of equality, but then began to become more unequal in the later part of the decade. This would become much more dramatic and obvious in the 1980s after Reagan came in.

As Piketty has shown, this pattern was happening in other high income nations as well, although the details of how the patterns changed varied somewhat from nation to nation. But in general the long decline of inequality that began at the end of the 1920s or so came to an end in the mid-1970s, apparently following that first oil price shock in 1973 that ended the post-WW II period of higher economic gtrowth.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/11/business/dealbook/trump-tariffs-canada-lumber.html

June 11, 2018

How Trump’s Lumber Tariffs May Have Helped Increase Home Prices

By Peter Eavis

Want to better understand what may happen in the United States economy as President Trump pursues his combative trade policies?

Look no further than the lumber that goes into many houses in the United States….

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/21/business/lumber-price.html

June 21, 2021

As Lumber Prices Fall, the Threat of Inflation Loses Its Bite

Costs soared partly because of do-it-yourselfers’ spending stimulus checks, but a month of declines show that consumers aren’t about to trigger runaway increases.

By Matt Phillips

From sawmills to store shelves to your own hammer swings, lumber can tell you a lot about what’s going on in the economy right now.

Lumber prices soared over the past year, frustrating would-be pandemic do-it-yourselfers, jacking up the costs of new homes and serving as a compelling talking point in the debate over whether government stimulus efforts risked the return of 1970s-style inflation….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EWfg

January 15, 2018

Producer Price Index for lumber and wood products, 1980-2021

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=CU0I

January 15, 2018

Producer Price Index for lumber and wood products, 2007-2021

(Percent change)

The June 2018 story may have been interesting back then. I looked at the 5-year window in Menzie’s source which shows the level of lumber prices (which is what you should be showing too as percent changes isn’t the real story).

These prices did rise considerably in the first part of 2018 but then they retreated later in the year. So we had only a temporary increase in lumber prices. I’m not sure why it was temporary – did Trump back off of these tariffs or did lumber importers find other sources?

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-06/23/c_1310023669.htm

June 23, 2021

Over 1.07 bln doses of COVID-19 vaccines administered in China

BEIJING — Over 1.07 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered in China as of Tuesday, the National Health Commission said on Wednesday.

[ Chinese COVID-19 vaccines continue to be administered at a daily rate of 20 million doses. ]

What’s the point of even a trillion vaccines if they don’t even work.

Good point but trust me on this one. Anne (ltr) will not even acknowledge it.

An interesting story on the history of the lumber trade war as well as where this may be heading:

https://www.politico.com/news/2021/06/22/canada-lumber-mills-us-deal-495496

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/23/business/beef-prices.html

June 23, 2021

Your Steak Is More Expensive, but Cattle Ranchers Are Missing Out

Demand for beef is spiking as people dine out and grill, but the profits aren’t being evenly distributed. Ranchers blame the big meatpacking companies.

By Julie Creswell

At Harris’ in San Francisco — a quintessential American steakhouse with dark wood, cozy leather booths and dry martinis — the price of the popular eight-ounce filet mignon with two sides recently increased $2 to $56.

It’s even more expensive for the restaurant.

Michael Buhagiar, its chef and owner, said he was now paying 30 to 40 percent more for that steak than he did a year ago. Raising his prices makes up only some of that difference, he said, “but we’re not trying to scare away customers.”

About 1,700 miles to the east, Brad Kooima scans the 3,000 cattle in his feedlot in Rock Valley, Iowa, on the South Dakota border. These days, he’s losing $84 a head.

“The frustration for producers like myself is that you’re looking at a situation where demand for beef, domestically and globally, has never been this good,” Mr. Kooima, 63, said. “And we’re not making any money.”

In the postpandemic world, the global supply chain is twisted and broken. As demand for food, vehicles, clothing and other goods has surged, producers and suppliers are struggling to keep pace, either unable to obtain the raw materials or workers needed to make automobiles, ketchup packets and popular drinks at Starbucks.

In the U.S. cattle industry, that chain is dominated by just four meatpacking conglomerates, and their profits are raising tensions. While diners at restaurants and shoppers in grocery stores experience sticker shock from sharply higher prices for ground beef and prime steaks, ranchers say they are barely breaking even or, in some cases, losing money.

They point a finger at the Big Four companies, which account for more than 80 percent of the processed beef sold in the United States: Cargill, JBS, Tyson Foods and National Beef….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EWJW

January 15, 2018

Global price of Beef, 2007-2021

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EWK3

January 15, 2018

Global price of Beef, 2017-2021

(Percent change)

Correction:

The graphs on Global price of Beef depict cents per pound, rather than percent change.

Take this graph back to 1990. Over the past 30 years the nominal price of beef (wholesale I bet) has increased by 110%. Over the same period, the overall CPI has increased by 110%. So yea beef prices are volatile and have risen even in real terms lately. But from 1990 to 2019, real beef prices declined.

When Obama first became President, real beef prices were really low. But during the Obama years we had a beef boom. So all those hick cattle ranchers should have loved Obama and hated Bush43.

“They point a finger at the Big Four companies, which account for more than 80 percent of the processed beef sold in the United States: Cargill, JBS, Tyson Foods and National Beef”

The middlemen in this sector have established a lot of monopoly power indeed. Where is the anti-trust enforcement?

The more expensive the meat the better for health and the environment.

Thank you Michael Bloomberg. Now how high of a tax do you wish to impose on sodas?

Kudos to pgl for bringing up anti-trust, but howls of derision for not mentioning the massive government subsidies that support inputs to beef production…a total violation of the fundamentals of free trade:

“ According to recent studies, the U.S. government spends up to $38 billion each year to subsidize the meat and dairy industries, with less than one percent of that sum allocated to aiding the production of fruits and vegetables.6 Most agricultural subsidies go to farmers of livestock and a handful of major crops, including corn, soybeans, wheat, rice, and cotton, with payments skewed toward the largest producers. Corn and soy inputs, in particular, are heavily subsidized crops for the production of meat and processed food by some of the world’s largest meat and dairy corporations. These farm subsidy programs supplement adverse fluctuations in revenues and production, and purchase farmers’ insurance coverage, product marketing, export sales, and research and development.7 This means that while shoppers pay lower immediate prices at the checkout counter, their tax dollars fund major meat operations and advertising. Meanwhile, meat and dairy producers accrue yearly retail sales to the tune of 250 billion dollars.”

https://jia.sipa.columbia.edu/removing-meat-subsidy-our-cognitive-dissonance-around-animal-agriculture

Funny how this rarely got mentioned byeconomists posing as public intellectuals in boosterism for free trade…except by “unreasonable” nations trying to get the US to practice the free trade it hectored it’s trading partners with!

Economists never criticize ag subsidies? Lord – your little parade is either stupid or dishonest if not both.

Using some obscure tool called Google, I found all sorts of research on the incidence of farm subsidies including this paper:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/598688

I also found an accounting of the USDA subsidies from 1995 to 2020 which apparently averaged around $10 billion per year with 78% of that going to the 10 largest farm entities. Of course none of this surprised me since I have read similar accounts before.

Of course JohnH is clueless as to the actual research on this or any economic issue as he is too lazy to even check. So he continues to rant and rave over what economists care about – which of course is a total waste of time.

You’re wrong. It’s been written about many, many times since I started paying attention in the late 80s. No one is paying attention except when, like you, they want something to gripe and moan about. The public, the media, and the Congresscritters have no excuse for not knowing except that they choose to not know it every time the farm bill is due to be reauthorized. Instead, we hear about the struggling family farm and those noble farm families, not about corporate farms and the highly concentrated agribusiness sector.

“It’s been written about many, many times since I started paying attention in the late 80s. No one is paying attention except when, like you, they want something to gripe and moan about.”

Precisely. But remember if JohnH was not whining with his usual intellectual garbage he would cease to exist. Just ask any one who followed Mark Thoma’s former blog. He has been writing the same pointless, dishonest, and stupid comment for many, many years.

I decided to reread this drivel from JohnH which in its odd way contradicts itself. He claims that economists are boosters for free trade (not true) and economists cannot be bothered to criticize agricultural subsidies (also not true). I guess in his endless pointless rage he has not figured out that subsidizing a major export sector is a deviation from free trade. Of course our European trading partners note this all the time but I guess JohnH has never noticed this as well.

JohnH: Back in the early 1980’s, I worked on a book by Peter Navarro, called the Policy Game, where *in one entire chapter* we called out the massive subsidies being granted the ag industry. There has been plenty of outrage over the decades among mainstream economists. It’s just that you weren’t paying attention.

But you did not publish it in the NYTimes so it does not count in JohnH’s world.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EXJ9

January 30, 2018

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product and Real Median Family Income for United States, 1954-2019

(Indexed to 1954)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EXJg

January 30, 2018

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product and Real Median Family Income for United States, 1954-1979

(Indexed to 1954)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=EXJl

January 30, 2018

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product and Real Median Family Income for United States, 1979-2019

(Indexed to 1979)

https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2016/12/the-puzzle-of-real-median-household-income/

December 1, 2016

The puzzle of real median household income

The graph above shows two often-reported series that look at a measure of income adjusted for inflation and population: real median household income and real per capita GDP. They should be similar, but there are quite a few differences. For example, median household income has stagnated for about two decades while per capita GDP has steadily increased. Let’s try to straighten out this puzzle….

— Christian Zimmermann

https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2015/05/the-mean-vs-the-median-of-family-income/

May 28, 2015

The mean vs. the median of family income

FRED has several datasets to help you investigate the distribution of income. One of them is the Income and Poverty in the United States release from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The graph above shows real family income in the United States in constant (2013) dollars. The mean is the average across all families. The median identifies the family income in the middle of the sample for every year: half of incomes are higher, half are lower. We quickly learn three things from this graph: 1. Family income has been growing much more slowly since the 1970s. 2. There are several episodes of declining income, and they become increasingly long and deep. 3. Median and mean incomes are diverging….

— Christian Zimmermann