A CNN headline notes “A key measure of inflation surged to a new 30-year high”, with that key inflation measure being the year-on-year (y/y) personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation, very similar to a headline a month ago. But in any case, by focusing on the y/y rate, they missed the main message In today’s release — that month-on-month (m/m) annualized PCE inflation was down from March peak, from 7% to 4% (and roughly the same as in July). Moreover, the core counterpart was also down from the April peak, from 7.7% to 4.1% (3.6% y/y hitting the Bloomberg consensus on the nose, and a little higher than m/m consensus.)

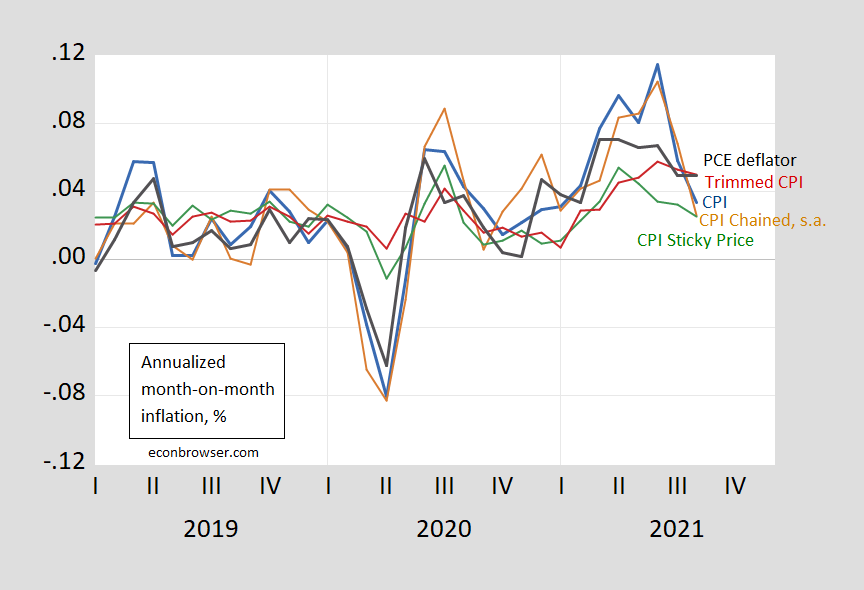

This personal income and expenditures release rounds out the inflation measures for August, so we have the following:

Figure 1: Month-on-month annualized inflation from CPI-all urban (blue), from personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator (black), chained CPI (brown), sticky price CPI (green), and 16% trimmed mean CPI (red). Chained CPI inflation seasonally adjusted by author. Source: BLS, Atlanta Fed, Cleveland Fed, via FRED, and author’s calculations.

The general discussion stressing y/y changes is understandable, but frustrating as it really tells almost as much about the past as the present, in the current context.

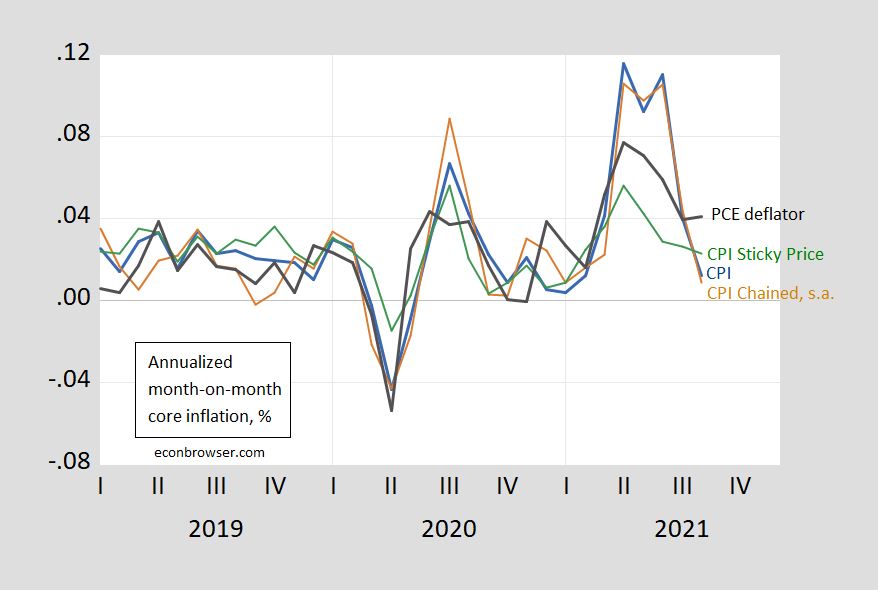

What about core measures? The core CPI inflation rate was also sharply down, as shown in Figure 2 (no trimmed core shown).

Figure 2: Month-on-month annualized inflation from CPI-all urban (blue), from personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator (black), chained CPI (brown), and sticky price CPI (green). Chained CPI inflation seasonally adjusted by author. Source: BLS, Atlanta Fed, Cleveland Fed, via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Looking to components of the PCE deflator, goods inflation is up (0.6% vs. 0.4% m/m) while services is inflation is flat at 0.4% (m/m).

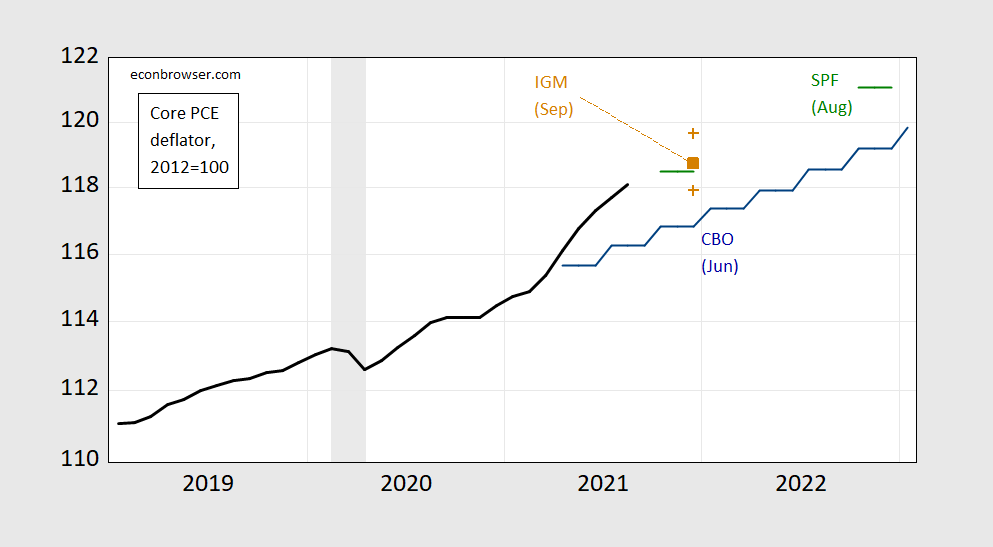

What does the core PCE price level look like relative to forecasts. Figure 3 depicts on a log scale the reported series, and forecasts.

Figure 3: Core personal consumption expenditure deflator as reported (black line), CBO (blue line), Survey of Professional Forecasters (green line), FT-IGM (tan large square), FT-IGM, and 80%ile band (tan +), 2012=100, all on log scale. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA via FRED, Philadelphia Fed SPF (August), and FT-IGM survey (September), CBO Economic Outlook (July), NBER, and author’s calculations.

If the core PCE deflator rises at 0.13% m/m (1.6% annualized) for the remainder of the year, then we’ll hit the IGM/FT median survey level.

A much simpler Page 1 graph from the BLS:

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf

It looks like the very definition of transient.

Thanks for the link. BLS’s graphs make the point Menzie was trying to make very clearly and simply. At the risk of repeating myself – this hack reporting by CNN is Faux News like.

CNN could not be bothered to also note that PCE excluding food and energy has remained at 3.6% even on their precious annualized basis. Come on CNN – we already have Faux News.

Ever editor worth their salt would require every reporter to include this chart over the entire 2019 to current so readers can see what is really going on:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL

Whoever wrote this report is a dork. His or her editor is incompetent.

The San Francisco Fed publishes PCE inflation dispersion data every month:

https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/pce-personal-consumption-expenditure-price-index-pcepi/

Take a tour through the tabs and you’ll see (I think) that the dispersion of price increases has been elevated and remains so, but is moderating. Supply problems help account for the wide range of goods which have increased in price. Supply problems aren’t over and may be growing worse – recent reports of China’s electricity rationing and of transportation worker burn-out are reason for concern.

But for now, inflation dispersion is improving by several measures. We have supply problems, so demand-management – through caution in fiscal and monetary policy – doesn’t look optimal to me. It looks like surrender. Policy explicitly and directly aimed at resolvig supply problems is the right approach. To the extent that caution on fiscal and monetary policy would hinder efforts to address supply problems, it would be counterproductive.

Speaking of counterproductive, policy to address supply problems doesn’t include extensive efforts to controlling climate change would be a disaster.

Another possible source of continuing or worsening supply problems is that apparently there have been shutdowns in Vietnam of some facilities that produce inputs for our production activities.

macriduc,

BTW, just for the record, even though i gave you a hard time about that Thucydides link, I mostly agree with you, almost as much as Moses Herzog does. Heck, while he agrees with you 98.27491 percent of the time, my latest estimate is that i agree with you 95.16389 percent of the time. So, keep up the generally good work! :-).