The employment release for October provided lots of interesting facts. First employment growth is faster than anticipated, and second was faster in September than originally estimated.

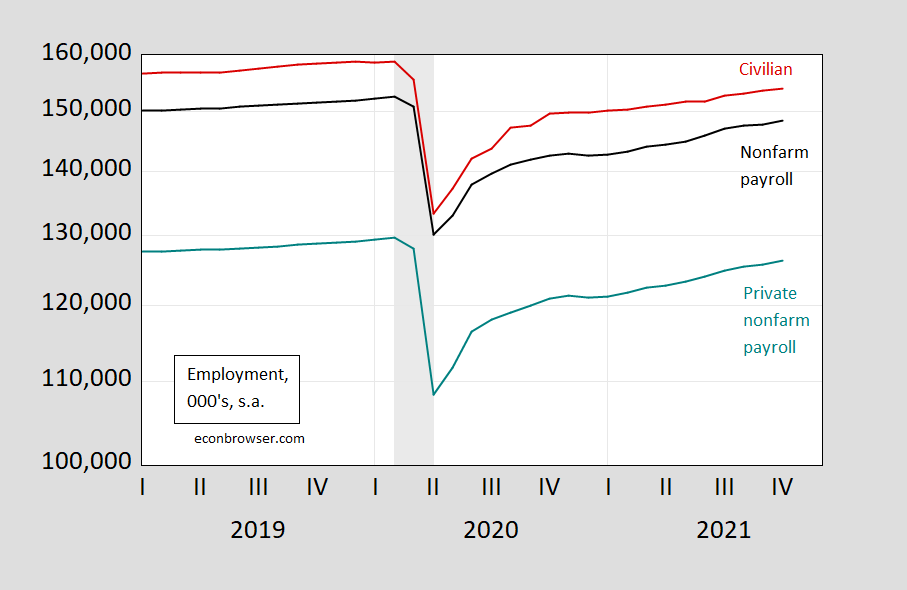

Figure 1: Nonfarm payroll employment (black), private nonfarm payroll employment (teal), civilian employment (red), all in 000’s, s.a. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER.

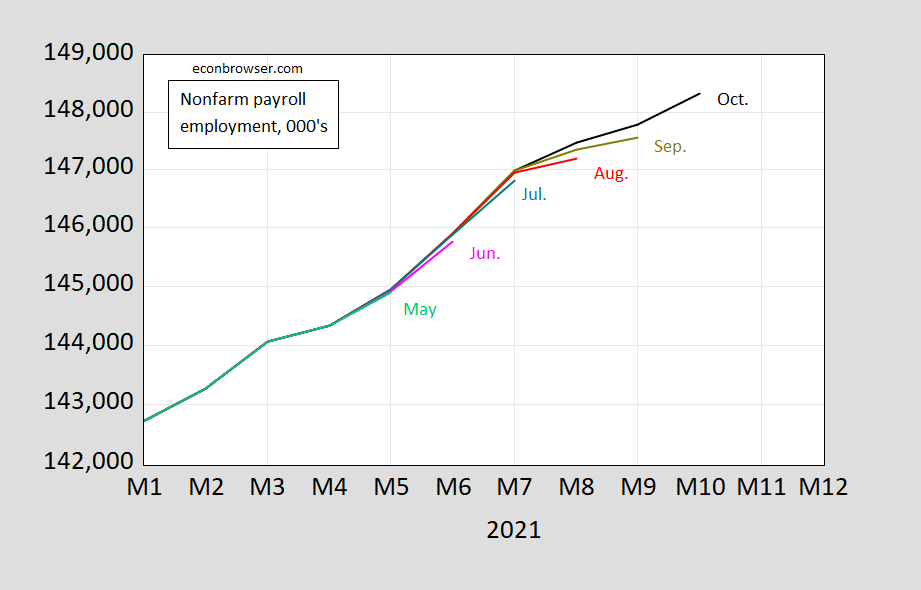

The originally lackluster September numbers were upwardly revised substantially. This is a pattern that’s occurred over the past five months, although less significantly so in the previous instances.

Figure 2: Nonfarm payroll employment in October (black), in September (chartreuse), August (red), July (teal), June (pink), May (light green), all in 000’s, s.a. Source: BLS.

This serves as a reminder that the first read of the employment figures are an estimate. The mean absolute revision in the monthly changes between first and second estimate is 48 (in thousands), and between first and third is 61 (full results at BLS).

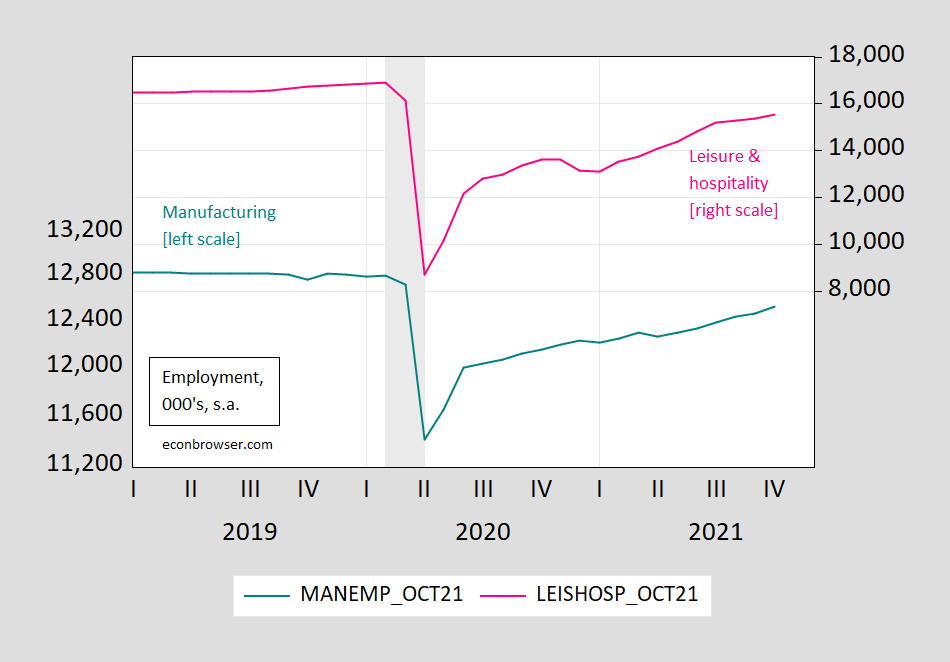

Note that growth in high contact services roughly doubled in pace going from August to October, which has been attributed to the waning of the impact of the Delta surge. There was an acceleration in manufacturing, but much less pronounced.

Figure 3: Manufacturing employment (teal, left log scale), leisure and hospitality employment (pink, right log scale), all in 000’s, s.a. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER.

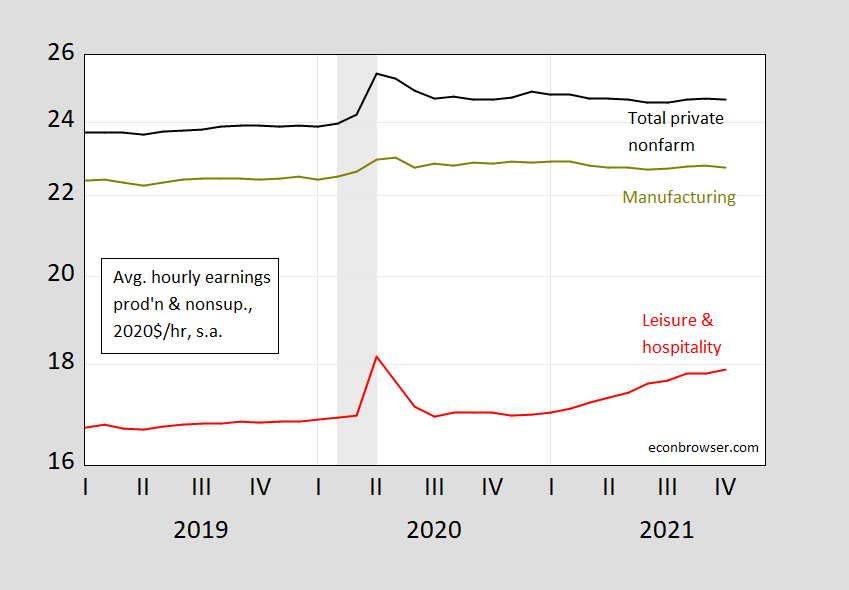

Finally, while there are worries about inflation eroding wage gains, it’s important to note that average real (CPI deflated) wages are higher than they were at the outset of the pandemic, for the entire private sector, for manufacturing. And for leisure and hospitality, real wages are far above what they were pre-pandemic, and still rising smartly.

Figure 4: Nonfarm payroll production and nonsupervisory average hourly earnings (black), manufacturing (chartreuse), leisure and hospitality (red), all in 2020$, s.a. (CPI deflated). October observation for earnings uses nowcasted CPI as of 11/5. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, Cleveland Fed, NBER, and author’s calculations.

If one is concerned with the real income of those at the lowest end of the pay spectrum — say in leisure and hospitality –, one should be happy to see this latter trend (5.6% y/y, 5.0% m/m AR, using nowcasted October CPI).

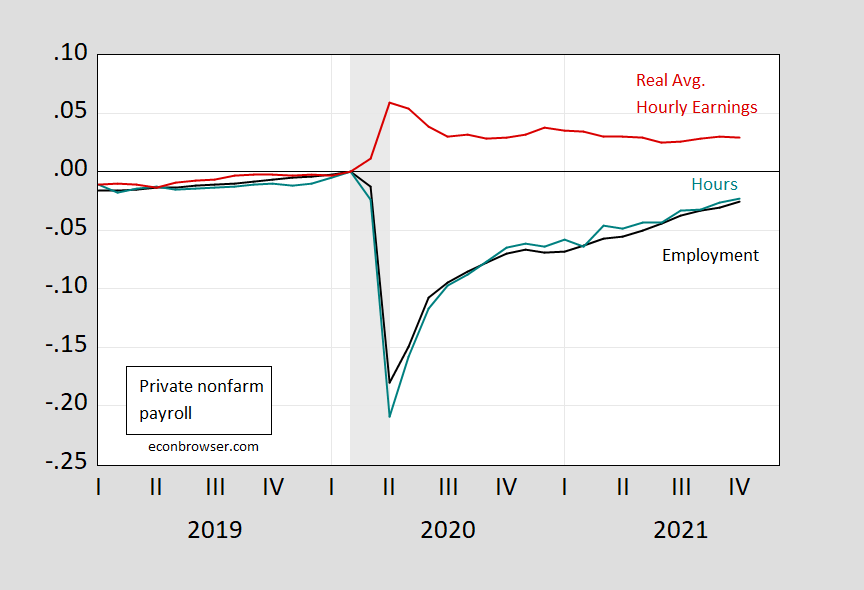

A final snapshot of the private sector employment, hours, and real wages:

Figure 5: Private nonfarm payroll employment (black), aggregate hours for production and nonsupervisory workers (teal), real average hourly earnings in 2020$/hr (red), all s.a. October observation for earnings uses nowcasted CPI as of 11/5. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BLS, NBER, Cleveland Fed, and author’s calculations.

Very useful information. Now I guess I do not have read Dean Baker’s email as you have covered just about everything!

https://www.cepr.net/jobs-2021-11/

November 5, 2021

Economy Adds 531,000 Jobs in October; Unemployment Falls to 4.6 Percent

By DEAN BAKER

The rise in the index of aggregate hours since July is equivalent to adding 498,000 private sector jobs a month

The economy added 531,000 jobs in October, as the unemployment rate fell to 4.6 percent, a level not reached following the Great Recession until February 2017. The jobs numbers for the prior two months were also revised upward by 235,000 to bring the three-month average to 442,000.

It’s also worth noting that private sector employment grew even more rapidly, adding 604,000 jobs. The hours-worked index, which only measures private sector employment, has risen by 1.2 percent in the last three months, which would translate into 498,000 private sector jobs per month if there were no change in hours. Many employers who are unable to hire are likely increasing the hours for the workforce they have.

[Graph]

Unemployment Falls for Most Groups

The drop in the unemployment rate was much larger than most analysts had expected, especially after a 0.4 percentage point decline in September. It has fallen by 1.3 percentage points since June. The least educated saw the largest drop in unemployment with the rate falling by 0.5 percentage points for those without a high school degree to 7.4 percent, and 0.4 percentage points for those with just a high school degree to 5.4 percent. The unemployment rate for college grads edged down 0.1 percentage points to 2.4 percent, which is 0.3 percentage points above its pre-pandemic average.

The unemployment rate for Blacks and Asian Americans was unchanged at 7.9 percent and 4.2 percent, respectively. It fell 0.4 percentage points to 5.9 percent for Hispanics.

Wage Growth Remains Strong ….

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/05/opinion/great-resignation-quit-job.html

November 5, 2021

Wonking Out: Is the Great Resignation a great rethink?

By Paul Krugman

Life is full of surprises. But there are surprises, and then there are surprises.

What I mean is that most of the time, when something you weren’t anticipating happens, you quickly realize that it’s something you could and maybe even should have seen coming, at least as a possibility. Of course air traffic control delays caused me to miss my connection. Or, to take an economistic example, few anticipated the 2008 financial crisis, but once it happened economists realized that it fit right into both their theoretical frameworks and historical patterns.

Sometimes, however, events take a turn that leaves you wondering what’s going on even after the big reveal.

Right now the U.S. economy is experiencing a very old-fashioned bout of inflation, with too much money chasing too few goods. That is, booming demand has collided with constrained supply, so prices are rising.

But there are really two kinds of supply constraint out there, and some are more comprehensible than others.

Not many people anticipated the now famous supply-chain issues — the ships steaming back and forth waiting to be unloaded, the parking lots stacked high with containers and the warehouses that have run out of room. But once they began happening, those issues made perfect sense. Consumers who were afraid to buy services — to eat out, to go to the gym — compensated by buying lots of stuff, and the logistical system couldn’t handle the demand.

On the other hand, the Great Resignation — the emergence of what look like labor shortages even though employment is still five million below its prepandemic level, and even further below its previous trend — remains somewhat mysterious….

Teachers were a bit of a drag on employment. Private hiring topped 600k.

Big upward revisions, so hand wringing was wasted.

Wage gains in high – labor public-facing jobs looks like Baumol’s revenge.

second that.

Well done Chinny

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=vtyk

January 4, 2020

Local and State Government employment, 2020-2021

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=vlm6

January 4, 2020

Local and State Government Education Employment, 2020-2021

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Hy9b

January 4, 2018

United States Employment-Population Ratios for Men and Women, * 2017-2021

* Employment age 16 and over

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=sxNb

January 4, 2018

Employment-Population Ratios for White, Black and Hispanic, * 2017-2021

* Employment age 16 and over

New to your blog, so I apologize if this has been discussed: Is decreased legal and illegal immigration a factor in the large number of unfilled job openings? If so, how large a factor?

Thank you for your blog, wonderful information!

Todd Ramsey: I haven’t. A recent Vox column quotes Nobel prize winner Abhijit Bannerjee on the subject, so best to consult that article for some nuanced assessment and leads for further research.