Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Ron Alquist (Senior Economist and Policy Advisor, Financial Stability Oversight Council), Benjamin R. Chabot (Knowledge Leader, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago), and Ram Yamarthy (Senior Economist, Office of Financial Research, U.S. Treasury). The views expressed in this blog post are the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of the Financial Stability Oversight Council, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Federal Reserve System, the Office of Financial Research, or the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Research in economic development points to institutions that protect property rights as a determinant of long-term income growth. North and Thomas (1973), among others, argue that property rights provide the necessary incentives to accumulate human and physical capital. An equally well-established body of research views financial markets as necessary for economic development. Since at least Schumpeter (1912), economists have argued that well-functioning financial markets improve the allocation of capital and promote growth by reducing transaction costs and information asymmetries.

We link these two ideas in a new paper (Alquist, Chabot, and Yamarthy 2022). Specifically, we examine whether the cost of capital of foreign equities traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) in the late 19th century reflected cross-country differences in institutional quality and whether those differences are related to economic growth. The evidence we find is consistent with both ideas, indicating that the quality of institutions influences the pattern of growth, in part, through its effect on risk premia and investment.

The late 19th century is well suited to studying how the international equity market priced the quality of property-rights institutions. During that period, Great Britain invested in a diverse set of countries, including those that did not share a common legal and accounting framework and were not under British colonial control. These investments were long-lived and derived their cash flows from real assets located in foreign countries. Although British citizens managed the investments, the projects outside the Empire were in foreign jurisdictions, creating the risk that contracts were unenforceable because the requisite institutions that protected property rights were weak or absent.

Further, the unique circumstances of that period permit us to investigate whether the risk premium related to weak contract enforcement influenced later growth. In the late 19th century, British overseas investment financed infrastructure projects around the globe, including railways, port facilities, and the mines and plantations that produced primary products for export (see, among others, Clemens and Williamson 2004). By focusing on that period of investment-driven growth, we can test the idea that the quality of the historical institutions shaped the long-run path of development through the effect on investment.

The London Stock Exchange Data

To investigate these questions, we use a data set consisting of 1,808 British and foreign equities from 52 countries traded on the LSE between 1866 and 1907. We collected the price data, quoted in British pounds, from the Friday official lists published in the Money Market Review and the

dividend payments and shares outstanding from the Investor’s Monthly Manual and The Economist. We sampled the stock prices every 28 days between January 1866 and December 1907, which resulted in 13 four-week months per year. The sample consists of 295,440 28-day holding period returns corrected for dividends, stock splits, and special payments. Chabot and Kurz (2010) also use these return data.

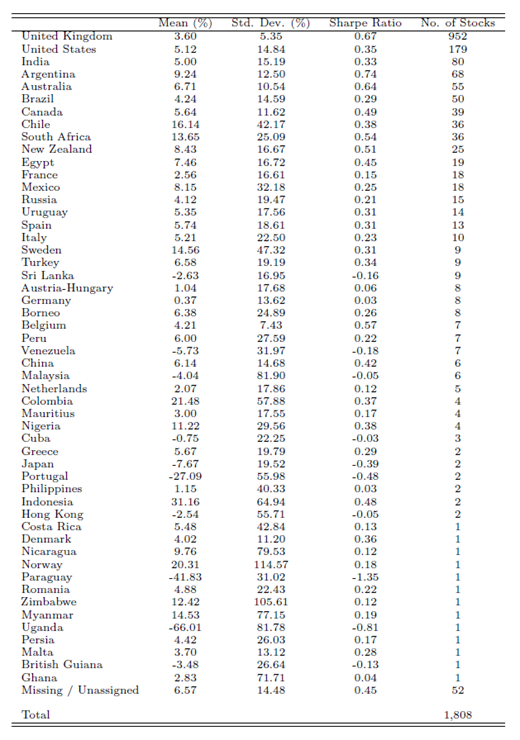

Table 1 provides the summary statistics of the firm-level excess returns by country, where we use the 28-day London Banker’s bill rate as the risk-free rate. More than half the firms are British (950), followed by the United States (179), India (80), Argentina (68), Australia (55), and Brazil (50). British firms offered one of the best risk-return tradeoffs. Although expected returns are low in absolute terms, so too is risk, as measured by the standard deviation. Only Argentina and Australia have comparable Sharpe ratios.

Table 1 – Country Return Summary Statistics

This table reports the annualized means, standard deviations, and Sharpe ratios of the country portfolio returns. The returns are equally weighted within each country. The portfolios are ranked in descending order by the number stocks associated with each country. The column “No. of Stocks” reports the number of unique stocks by country.

This table reports the annualized means, standard deviations, and Sharpe ratios of the country portfolio returns. The returns are equally weighted within each country. The portfolios are ranked in descending order by the number stocks associated with each country. The column “No. of Stocks” reports the number of unique stocks by country.

Institutions and the Equity Cost of Capital

Guided by the predictions of a simple two-period portfolio allocation model, we first investigate whether the risk-adjusted cost of capital in the 19thcentury reflected cross-country differences in institutions. We construct common risk factors such as market returns, size, value, and momentum (e.g., Fama and French 1993) using the 19th-century equity return data to perform the risk adjustment. The risk-adjusted cost of capital at the firm level is the constant term or so-called alpha from a time-series regression of the firm’s returns on those factors.

We use two indicators of institutional quality–a dummy variable that captures the country’s predominant legal tradition from La Porta et al. (2008) and the European settler mortality rate during the early settlement period from Acemoglu et al. (2001). For legal origins, the hypothesis is that firms in countries with a British common law tradition pay a lower equity cost of capital. because that tradition provides more robust protections to outside investors. For settler mortality, the idea is that Europeans had less incentive to establish secure property rights and prevent the formation of extractive, investment-retarding institutions in regions with high settler mortality rates. We also include a modern-day index of expropriation risk identical to the one used in Acemoglu et al. (2001).

In the regression analysis, we include only non-European countries. Limiting the sample in this way is consistent with Acemoglu et al. (2001) and La Porta et al. (2008). They examine whether the legal traditions and property-rights institutions that emerged in Europe had spread globally. Omitting non-European countries from the sample reduces the number of equities to about 625 from 1,808 and the number of countries to about 25 from 52. The sample size also varies with the availability of the other data and their overlap with returns.

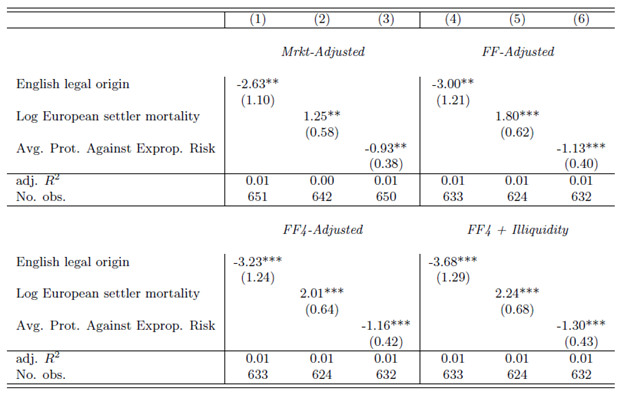

Table 2 reports the results of the panel regressions, where we regress firm-level alpha onto measures of country-specific institutions. Operating in a country without an English legal tradition or with weak property-rights institutions is associated with a higher firm-level cost of capital, consistent with economic reasoning. A country with a 1% higher settler mortality rate had, on average, a 1.8 percentage point higher annual alpha using the Fama-French adjusted returns. Despite a smaller sample, we obtain comparable results using country-level equity returns.

Table 2 – Institutions and Foreign Equity Returns

This table reports the asset pricing results obtained by regressing individual firms’ risk-adjusted returns onto country-level measures of institutional quality. Going clockwise, the first panel uses returns adjusted using the British market factor; the next two panels use the three British Fama-French factors and momentum in the third panel; in the final panel, we include the illiquidity factor. The risk adjustment removes time-series variation with the factors and cross-sectional industry fixed effects. The coefficient values from all regressions are annualized and converted to percentage terms. Standard errors and t-statistics account for robust standard errors.

This table reports the asset pricing results obtained by regressing individual firms’ risk-adjusted returns onto country-level measures of institutional quality. Going clockwise, the first panel uses returns adjusted using the British market factor; the next two panels use the three British Fama-French factors and momentum in the third panel; in the final panel, we include the illiquidity factor. The risk adjustment removes time-series variation with the factors and cross-sectional industry fixed effects. The coefficient values from all regressions are annualized and converted to percentage terms. Standard errors and t-statistics account for robust standard errors.

Equity Cost of Capital and Actual Expropriations

Given this evidence, it is natural to ask whether actual seizures of private property in the late 19th century reduced payoffs to British investors from their foreign investments. Actual expropriations during this period were rare (Lipson 1985), making the idea challenging to test directly.

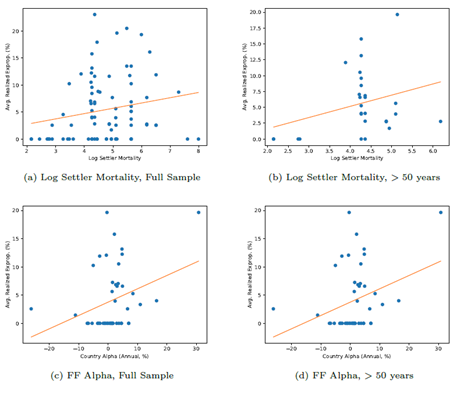

However, to examine this idea using the available data, we use data on the expropriation of U.S. foreign direct investments (FDI) between 1929 and 2004, which Tomz and Wright (2010) collect. Figure 1 shows the correlation between the historical cost of capital, Acemoglu et al.’s (2001) log settler mortality measure, and FDI expropriations in the 20th century. This evidence supports the idea that country risk premia reflect, in part, the pricing of future expropriations.

Figure 1 – Historical Institutions and Expropriations of FDI

The top two scatter plots depict the relation between average expropriations of U.S. foreign direct investments in the 20th century and log settler mortality (subfigures (a) and (b)). The bottom two plots examine the same relation using country-specific risk-adjusted returns. The total country cost of capital is computed by aggregating risk-adjusted returns that correct for the three Fama-French factors. In each half (top vs. bottom) of the figure, the left subfigure conditions on the full cross-country sample, while the right focuses on countries with foreign direct investment expropriation data for at least 50 years.

To summarize, we find consistent evidence indicating that 19th-century British investors discounted more heavily equities in countries with weak property rights institutions. Moreover, the quality of those institutions correlates with actual FDI expropriations during the 20th century.

Cost of Capital, British Investment, and Growth

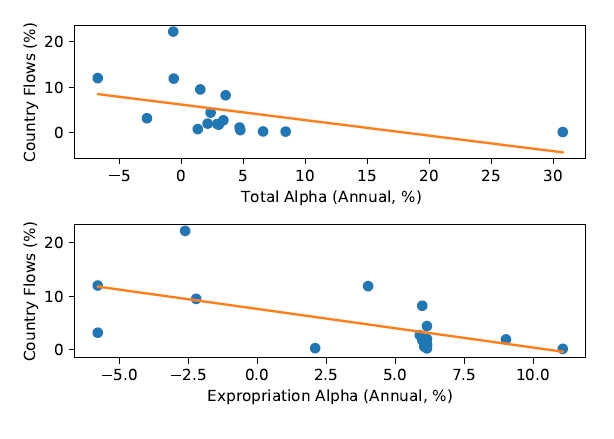

Next, we examine whether the cost of capital and the component related to expropriation risk correlates with British foreign investment flows during the late 19th century.

The top panel of Figure 2 depicts the relation between British capital flows and alphas, and the bottom one shows the results using expropriation alpha. In both cases, the correlations are negative, and the statistical evidence in favor of the negative relation becomes stronger when we omit an outlying observation (Indonesia) from the sample.

Figure 2 – Historical Cost of Capital and British Capital Flows

This figure depicts the scatter plots of the relation between 19th-century British capital flows and the country-level total cost of capital (top panel) and the expropriation-related component of the cost of capital (bottom). The total cost of capital in a country is calculated by aggregating risk-adjusted returns based on the three Fama-French factors. The expropriation-related cost of capital is computed by extracting the fitted value from a cross-country regression of the total cost of capital onto the log of European settler mortality.

We also investigate the relationship between the 19th-century cost of capital and present-day real GDP per capita. The economic reasoning behind such relies on the premise that institutional quality is a fundamental driver of the historical cost of capital and present-day incomes. In line with this intuition, Figure 3shows the estimated coefficients are all negative and are statistically significant in most cases.

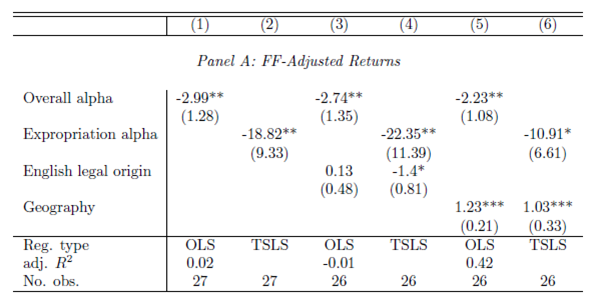

Table 3 – Historical Cost of Capital and Present-Day Income Per Capita

This table reports the results of regressing present-day income per capita levels onto the 19th-century cost of capital, the expropriation component of the cost of capital, the English legal origin dummy, and the index of environmental and geographic variables. This panel uses returns adjusted by the Fama-French three-factors and each column presents a different regression. Across all specifications, the dependent variable is the log of country-specific real GDP per capita in 2016. Column 1 examines the effect of the total cost of capital on present-day income levels. Column 2 replaces the total cost of capital with the expropriation-related component of alpha, based on a TSLS procedure using the European settler mortality measure of expropriation risk. Columns 3 and 4 control for a dummy variable indicating English legal origins. Finally, columns 5 and 6 control for an index of geographic and environmental variables based on temperature, latitude, and distance to coastline. Coefficients on both alpha variables reflect the effects of annualized alpha measures while t-statistics reflect standard errors controlling for heteroskedasticity in residuals.

As Table 3 shows, the estimated coefficient of -2.99 implies that a one percentage point increase in the annualized equity cost of capital is associated with a -2.95% real GDP per capita in 2016. The other estimated coefficients are of a similar magnitude, including when we control for legal origins and other geographic and environmental variables.

The estimated coefficients using the expropriation alpha suggest a 10-20% lower real GDP per capita for each percentage point increase in the risk-adjusted cost of capital. They are, in general, statistically significant at the 10% level.

Property-rights institutions can also shape long-run financial development because they protect investors from expropriation by elites or the government (Acemoglu and Johnson 2005). In a set of regressions not reported here but discussed in the paper, we show that present-day private credit and stock market capitalization ratios correlate with the 19th-century cost of capital and, specifically, the component related to institutional quality and expropriation risk.

Conclusion

We bring unique historical data to bear on whether investors value property-rights institutions and whether the premium related to the pricing of such institutions has implications for economic growth. The evidence broadly supports our hypothesis and is the strongest for the indicators that measure expropriation risk. These findings indicate that the quality of institutions influences the pattern of growth, in part, through its effect on risk premia and investment.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., 2005. Unbundling Institutions. Journal of Political Economy 113, 949-995.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J.A., 2001. The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. American Economic Review 91, 1369-1401.

Alquist, R., Chabot, B.R., Yamarthy, R. 2022. The Price of Property Rights: Institutions, Finance, and Economic Growth, Journal of International Economics 137. Link to Paper.

Bordo, M., Eichengreen, B., Kim, J., 1998. Was There Really an Earlier Period of International Financial Integration Comparable to Today? NBER Working Papers 6738. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chabot, B.R., Kurz, C.J., 2010. That’s Where the Money Was: Foreign Bias and English Investment Abroad, 1866-1907. Economic Journal 120, 1056-1079.

Clemens, M., Williamson, J., 2004. Wealth Bias in the Global Capital Market Boom, 1870-1913. Economic Journal 114, 304-337.

Fama, E.F., French, K.R., 1993. Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33, 3-56.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., 2008. The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins. Journal of Economic Literature 46, 285-332.

Lipson, C., 1985. Standing Guard: Protecting Foreign Capital in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. University of California Press, Berkeley.

North, D.C., Thomas, R.P., 1973. The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History. Cambridge University Press.

Schumpeter, J.A., 1912. Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Dunker & Humblot, Leipzig.

Tomz, M., Wright, M.L.J., 2010. Sovereign Theft: Theory and Evidence about Sovereign Default and Expropriation, in: Hogan, W., Sturzenegger, F. (Eds.), The Natural Resources Trap: Private Investment without Public Commitment. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp. 69-110.

This post written by Ron Alquist, Benjamin R. Chabot, and Ram Yamarthy.

This is cool and right up my alley, but the problem with both the common law and settler mortality effects is that their distribution in the world and within empires is not random. This is a 20+ year old question in the growth lit as readers likely know. While I buy the Acemoglu/Engermann stuff in broad strokes (the Acemoglu et al 2001 paper was hardly the last word) I think institutions are more complicated than whatever European empires happened to be able to impose on their colonies.

Moreover, settler mortality as an instrument for property rights specifically is questionable in its own right. Slave societies had robust property rights regimes, but they were also the places where settlers wouldn’t go very willingly due to health concerns (that’s *why* they were slave societies). Still, property rights over both slaves and plantation assets were paramount for the plantation economy. Plus, there’s interesting variation in property rights within the slave-driven regions: compare Barbados to Brazil in the 17th century, and you’ll see their plantations were run very differently, even though both places were terrible for settler health; the difference is in their debt remediation regimes (the Brits were more creditor-friendly).

In any case, a very interesting post.

Agree that legal heritage is not a very complete description of property rights regimes, but for the purpose of identifying quantifiable variables, I can’t think of anything better.

I’m not sure property rights in human property is a useful guide here. If a wealthy slave owner wanted land from a small-holding neighbor, was that smallholder as well protected by the legal system as the wealthy slave owner? Were private craftsmen able to collect payment from the rich and powerful? I don’t know, but I think those issues are mighty important for economic performance after the end of (legal) slavery.

Property rights in slaveholding societies were important regardless of the inequality of landholding slavery implied. Moreover, inequality between small landholders and big was a major element in non-slave societies, such as England — yet we admire the English common law as an example of good institutions with good incentives and good property-rights protections.

It’s not necessary for there to be perfect equality in legal protections (we don’t have that today) but it has to be good enough to allow new businesses to flourish. Ambitious small businesses have to raise capital and protect their business from (effectively) theft. Those could be slave-related businesses, too.

“Were private craftsmen able to collect payment from the rich and powerful?”

Yes, at least in the English system. Something that helped was mechanic’s liens, which put a claim on property that a contractor worked on but wasn’t paid for on time. Also, above and beyond “institutions,” reputation matters.

AndrewG:

Your points are well taken—a couple of observations in reply.

We are aware of the econometric problems with using settler mortality as an instrument, as Albouy (2012) has most forcefully argued. Indeed, we identify the expropriation alpha in the paper using a 2SLS regression in the same way that Acemoglu et al. (2001) identify the exogenous variation in institutions. The F-statistics from our first stage regressions, which have a sample size of about 25 countries, do not exceed the conventional statistical thresholds for the weak instrument test. For this reason, we report evidence based on both OLS and TSLS regressions.

Therefore, our argumentative strategy in the paper is not to present our findings as causal, a claim unsupported by the statistical evidence. Instead, we tested the idea from a variety of perspectives. For example, we included controls for geography and resource endowments in the regressions. Also, we looked at other implications of the underlying premise, such as the correlation between expropriation alpha and 19th-century British capital flows and actual expropriations in the 20th century.

That is, we tested several necessary conditions that follow from an explanation of foreign investment and growth based on the role of property-rights institutions. The evidence from practically all of those tests fails to contradict the premise of the property-rights institution hypothesis. Where there is conflicting evidence, we acknowledge it in the paper. The weaker statistical evidence is likely related to our tests’ lack of statistical power as we have a relatively small cross-sectional sample. The point estimates are generally stable in those regressions, but the standard errors become larger.

In sum, we acknowledge the domain over which our conclusions are supported by the evidence. In some ways, our data set is rich, and in others, it is limited, specifically in the size of the cross-section of countries. Nevertheless, in our view, one can still learn things from the data about equity risk premia and what British investors cared about during this unique period of investment-driven growth.

We are also aware of the conceptual problems with using the legal origins and settler mortality data but chose to take those measures as given. We used other modern-day measures of institutional quality, including present-day measures of expropriation risk and legal quality. Those regressions are a little unusual from a coneptual point of view in that we regress 19th-century alpha on a 21st-century measure of expropriation risk, for example. Nevertheless, as the paper discusses, our main results hold up in those regressions. But we have not found an alternative way to measure the many subtleties and nuances of institutional quality, relying instead on the preponderance of evidence using many different indicators that is consistent with the property rights hypothesis.

Specifically, we examine whether the cost of capital of foreign equities traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) in the late 19th century reflected cross-country differences in institutional quality and whether those differences are related to economic growth. The evidence we find is consistent with both ideas, indicating that the quality of institutions influences the pattern of growth, in part, through its effect on risk premia and investment….

[ A fascinating paper, but I do not understand the mix of severely exploited colonies and colonial peoples and, say, Germany, Italy, Sweden and Norway. South Africa may have had well-settled property rights but the property was stolen, and as Branko Milanovic has commented often property inequity to this day makes South Africa the most inequitable of nations and a nation of faltering development. The mix of countries studied as though Denmark were Zimbabwe is troubling. ]

If the results suggest that economies with certain characteristics perform better than other economies in terms of returns on equity and growth in output, without regard to colonial history, then we have prima facie evidence that something other than colonial history is at work.

Our priors should not be used to disqualify legitimate results. We analyze data to test our priors.

But this *is* a legitimate problem, and one of the reasons we don’t usually do cross-country growth comparisons like this anymore. There are too many things to model that contribute to differences in countries’ growth prospects. The key problem is the financial sector and financial frictions. The people to read about this are Duflo and Banerjee (2005 Handbook of Economic Growth) and colonial institutions may make the problem worse, not better. (The problem might be ‘better’ in the British Empire because they had a more modern financial system compared to other empires.)

As the paper’s references would indicate, Daron Acemoglu is also a good one to follow on this general topic.

If we aren’t doing cross-country analysis to the extent we once did, and we think we have good reason, we could be wrong.

Think of the most powerful fad in economic research in the second half of the 20th century – micro-foundation/rational expectation formalism. There is good reason to think that assumptions of rationality are as flawed as pre-Lucas assumptions about behavior, but we keep insisting that PhD students grind through the exercise.

Speaking of critiques, google “economic critique” and see how many different areas of research have had their formalism and assumptions called into question. Long list.

What we have in front of us is an empirical result. Any good empirical study is a starting point for further enquiry, not a final answer, but I stand by my objection to ltr’s objection. Her objection is a reflection of her priors – look through comments to see how often she mentions colonialism. She didn’t show that combining colonial economies with others is a problem in this specific piece of research. She merely asserted that it is.

I’m happy to hear objections to this piece of research, as written. I have no interest in a recitation of the big battles in economics as they apply to any piece of research. At some level, every bit of research ever done crosses some line drawn by some school of thought.

What’s right, and wrong, about this specific study?

My criticisms of this particular article are up top – you’ve already read them – and they are directly related to colonialism. Colonialism is what gives us the variation in both legal traditions and settler mortality (Spain went where the gold is because they were the first out the block; the rest followed in their own time). You may have noticed I’m not ltr’s biggest fan, but she has a point here.

If you think rational expectations and microfoundations are fads, then you can take that up with macro people – including the central bank economists who use them today. I’m no macroeconomist.

If you think not doing cross-country macro comparisons (particularly about long-run growth) is also a fad, that’s fine too, but I’ve thought about this particular issue a lot and I am on the side of Duflo and Banerjee plus the many leading macro-growth people writing before them. It’s very difficult to do convincing cross-national reduced-form studies of long-run growth because of the difficulty of modeling differences in financial systems, and finance is one of the biggest keys to development. These kinds of studies can still tell us something (we still cite Acemoglu’s article from 21 years ago) but there are very important limits to exercise. And it’s not for lack of trying – these studies used to be very popular.

@ AndrewG

Pretty cool, you got the authors of the papers to respond to your concerns. It has happened before on this blog but it’s relatively unusual for guest contributors, so it shows they were receptive to your beef and able to take mild criticism. This is to the authors’ credit. Not all authors to papers are open to criticism. See Nassim Taleb, who can’t even take critiques about his nutjob weight-lifting habits.

This is a good point. Putting aside this empirical study, one way to approach this is to start with geography. Geography determines the kinds of crops that can be raised in a place, and also the hostility to human habitation. This leads to certain kinds of institutions being developed. Those institutions explain differential growth in the modern era.

We can frame this in terms of slavery vs. democracy. In places that had relatively low populations at the beginning of the colonial era, such as much of North America and the Caribbean and Australia (despite what you may hear, there is historical, archaeological and genetic evidence of this), European colonizers had to get a bunch of people to the “New World” in order to work. Colonization in these places was a business short of labor supply. In places that were not hostile to human health, European settlers went willingly. In places that were terrible for human health (like the Caribbean and Brazil), no one would go willingly, so there was a market for slaves to be “imported.” (How very unlucky for West Africa.) But it just so happens that the places where slave agriculture was widespread were also places where certain cash crops were made, particularly sugar. Sugar agriculture incentivizes large-scale slave plantations – and very high inequality. In the places that were better for human habitation, there were fewer or less lucrative cash crops, and the incentives were to have smaller-scale farms. It’s easy to guess which places ended up with more egalitarian societies and which places got democratic institutions sooner. Similar stories can be told for some African and Asian colonies. (The slow development of “colonized” places with existing large civilizations – Mexico, India, China, etc. – have a somewhat different economic logic behind them.)

Acemoglu and his colleagues stress that hostility to human habitation made it harder for Europeans to bring their culture and institutions. But that assumes most or all European institutions were good, which is just not true. Encomienda was a European institution! No one thinks it was good for growth. But this framework, more associated with Engerman and Sokoloff, though it overlaps with Acemoglu, is largely free of that thinking. Geography determines institutions in a local way due to local conditions, not simply due to how much European “goodness” we get.

Andrew,

I don’t mean to get crosswise with you, but this assertion, as written, doesn’t follow:

“Acemoglu and his colleagues stress that hostility to human habitation made it harder for Europeans to bring their culture and institutions. But that assumes most or all European institutions were good, which is just not true.”

Acemoglu may assume goodness in European institutions, but saying that tough conditions prevented bringing those institutions is not the same as saying those institutions are good.

Nor does citing encomienda serve your point. Encomienda was a colonial strategy even in Iberia, a tool of war. The institutions in question in the London Exchange paper are largely institutions of civil society. Also, one set of institutions needn’t be all or mostly good to produce higher returns than another set, only better than the other set of institutions at producing returns and growth. Equality, fairness and humanity are not tested for in this research.

Take it as given that colonialism, war and it’s spoils are bad. Take it as given that not all European institutions are good. The question posed by the paper is whether one set of property rules is better at producing equity returns and economic growth than other sets of rules.

The authors seem to be asking whether an policy truism is true. I wonder if they have tried hard enough to falsify the truism. But as I said, any paper is just one step in the process of research. As a first cut at falsifying this truism, are there methodological problems here? If not, what’s next? If the question is whether colonialism is a separate factor driving returns and growth, how do we test that proposition?

This literature is both big and important and also very interesting so there’s no harm in getting into the weeds and digging out all the details!

When I say “Acemoglu’s argument” I’m talking about how I (and others) read his argument from around 2001, not necessarily how he sees things today. I’m not sure how his views have changed; the last thing I read of his was maybe from 2012 (he’s both prolific and mercurial).

“His argument” is that: the way that “good” institutions came from Europe is through settlers. So if settlers didn’t come in big numbers, they didn’t set up good institutions (Jamaica, Brazil, Cuba, etc.). Where they did come in large numbers, they set up good institutions (the US, Canada, Australia). There are some borderline cases, like South Africa.

Encomienda was a European labor market institution that was common in the Americas and helps explain bad long-run outcomes. I think it’s very relevant. Another relevant story is the American South: before the Revolution, these colonies were where English common law were strongest and looked most like English law. But what we see in the South is persistent long-run bad outcomes, and we almost entirely attribute that to slave agriculture. All European institutions. Many different kinds of institutions matter. And we have to remember that what we are trying to explain isn’t small gradations in growth, but the phenomenon called takeoff: an escape from the slow growth and Malthusianism that humanity experienced for most of history.

My big issue with papers like these is that legal origins and settler mortality aren’t random. They are selected by choices of colonial empires, which is why colonialism is so relevant to this question. And where empires end up colonizing isn’t random either. I don’t see how this isn’t a methodological question! It’s hard to tease out good comparisons (and we should respect people who try; these aren’t easy things to study). To be more precise, the famous legal origins literature took a lot of time (over many papers) to show gradations in the “quality” of legal origins (running from English common law to German/Scandinavian law, which was more flexible than pure civil codes, to civil code countries. That’s one way they made their argument convincing. To put that in “methodological” terms, continuous treatment is better than binary treatment. Still not very random, but you can make a better argument and try to single out the biggest confounders (no single methodology is perfect).

ltr:

As discussed in the blog post, we do not mix the European and non-European countries in the regressions, which would contradict the paper’s premise. We examine whether British investors demanded a higher equity risk premium from countries with institutions or legal systems that did not, in their view, adequately protect property rights in the regions of the world newly settled by Europeans. Table 1 reports the data for the entire sample in the data set, but in all of the regressions, we restrict the sample non-European countries. We further limit the sample by using several filters for the equity returns, including having a minimum number of stocks listed for a certain period. These filters are intended to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and obtain more precise estimates of expected returns.

Excluding the European countries from the sample is one reason why the sample size falls from 52 to about 25, depending on the specific regression. Another reason is the availability of other variables we control for, such as data on natural resource endowments. We discuss these issues in more detail in the paper and its appendix.

No disrespect meant, of course, but on further consideration this research needs lots of justifying. Rudyard Kipling meant well, but his ideas were already anachronistic in 1899.

Further explaining, colonially forced 19th century institutions in India are just not comparable to British institutions in instructing about growth differences. British exploitation through India and undermining of growth in India was long-lived and stark. This research essentially sets aside the nature of colonial exploitations, and as such strikes me as necessarily contrived. There was a reason India needed to be free of Britain to have a chance to grow properly.

“British exploitation through India and undermining of growth in India was long-lived and stark.”

Exploitation – like mercantilism, something you could measure with the current account – wasn’t the story in British India. Arguably the Brits brought lots of good things to India, like a competent civil service, lots of new technology like railways, and lots of financing. But the Brits indeed undermined the future growth, because at the end of the day they governed it like a foreign colony, not like their own country. Education was terrible, and famines common. The Raj got increasingly authoritarian. Not great for future growth prospects.

But none of this should absolve the leadership of independent India for most of the 20th century, who made terrible policy decisions. And we can say the same about independent China. Bad government policy is bad for growth.

Foreign investment and imperial exploitation: balance of payments reconstruction for nineteenth-century Britain and India

James S. Foreman-Peck

Economic History Review, 1989

https://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/ehsrev/v42y1989i3p354-374.html

I suppose it’s a reflection of the fact that results are bounded at zero, but in the panels of figure 1, there appear to be horizontal groupings at zero and on or more vertical groupings. Maybe I’m reading too much into those representations of the data, but it looks like there is more going on in the data than is described in the statistical results. Regularities of some kind.

I understand that including lots of countries in the analysts ought to correct for anomalies, but there are lots of countries represented by just one asset. Get a load of Norway – standard deviation 114.57, right up there with Zimbabwe. Seems unlikely to be a realistic representation of Norwegian asset performance for the period, but what do I know?

Macroduck:

Please see my response to ltr above, which partially answers your question about Norway. Norway is excluded from all the tests because it is a European country.

Norway listed only one stock during our sample period for a couple of years — a copper mine. The Norway country portfolio consists of a single equity, which explains its substantial standard deviation. We know equity returns are noisy, so asset-pricing tests are conducted using well-diversified portfolios of assets to mitigate that problem, a practice we follow. But a portfolio consisting of a single stock is the opposite of well-diversified.

As we show in our paper, mines have especially noisy returns. We include a table with average returns, standard deviations, and Sharpe ratios by industry. Mines, an industry listed separately in the primary sources we used to construct the data set, have a substantial standard deviation.

All of that to say, the single Norwegian mine is unlikely to represent the overall performance of Norwegian assets during that period, but nowhere in the empirical analysis do we include it.

The paper is interesting and worthy. But I find this a topic I don’t have a lot to contribute on. I guess it’s not very contributive, but I was just wondering, China property values are so high. I’m wondering how much higher Chinese property values would be if they allowed FDI and respected people’s property rights?? Of course it would be hard for foreigners to put any long-term trust in it, but surely a few brave souls would would stick their toes into the cold water. I don’t know, it just makes me curious what that would do to property values which are already precious.

Off topic –

Japan is working in a prototype ocean current electric power generation gadget named Kairyu. The ultimate goal is to use the Kuroshio Current, which runs alongside Japan’s east coast, to supply a large share of Japan’s power needs.

The Bloomberg title includes “deep ocean, which may be misleading. Kuroshio is part of an oceanic current system which runs to great depth in some places, but off the coast of Japan, the depth is only about 1km. That’s an advantage, both because of the reduced cost of construction, but also because the sharp reduction in depth causes the current to accelerate. Faster current, more horsepower.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-05-30/japan-s-deep-ocean-turbine-trial-offers-hope-of-phasing-out-fossil-fuels

If only they hadn’t shut down all their nuclear power plants.

I was directed to this from a Alan Blinder editorial in the WSJ. I am curious Professor Chinn’s, Macroduck’s, and “AndrewG’s” thoughts on it. I thought it was very fascinating, and puts a different spin on some of the garbage Larry Summers has been selling those who are easily led around by the nose:

https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/indicators-data/inflation-sensitivity-to-covid-19/

Super interesting! Great share. But I think Chart 2 speaks to Summers and the hawks’ point, and the fact that people like Janet Yellen (we don’t think she’s selling garbage, do we?) have admitted they were wrong about inflation. There’s also a point that a prominent macro person made when I asked them about this some weeks ago: even if it’s all supply shocks, saying the Fed can’t do anything is a cop-out. The AS-AD model we teach to undergrads tells us that while there’s a price to be paid, the Fed (and with bigger lags, fiscal policy) can do something about inflation through aggregate demand. (I am not a macroeconomist! But all these people I’m talking about are.)

You’re way too hard on the hawks. They were right. And in the current insane state of US politics (CPAC in Hungary, anyone?), this isn’t a lesson we can ignore. Biden’s approval on economic matters is 30%, and it’s all due to inflation. It’s possible this could have been avoided.

I wonder if MC thinks this might merit a post (if he hasn’t done one already on this – or if he has, maybe an update)?

@ Andrew G

I have two relatively short things to say related to your comment (respectfully):

1) Admitting that one’s self (i.e Yellen, i.e. Uncle Moses) was wrong about the level of inflation, is NOT the same as saying the amount of fiscal stimulus during a pandemic was “too much” or “too high”.

2) Raising unemployment is NOT an appropriate way or even an effective way to lower inflation <<—That's a public service announcement to macroeconomists who are under the mistaken impression that they "know it all"

5 dead if you count the shooter. This is not an abortion clinic, which would be a semi-natural assumption in our current context.

https://kfor.com/news/local/multiple-people-shot-at-medical-building-near-tulsa-hospital/

For whatever it’s worth, the section of the hospital or medical building where the murders occurred was related to orthopedic stuff.

Looks like ths shooter was a patient unhappy with care. So any old reason, once murder is in season.

Should we take some kind of solace in the fact it wasn’t random?? Honestly I don’t know anymore. What I will say is I have never understood it when the guy goes wacko at the factory, shooting people (“working stiffs” in the same boat he is in) he doesn’t even know, when he is pissed off at his boss for firing him. My weirdo take has always been, if you’re going to go nuts “make it count” and direct the anger at the original source of your angst. Yeah, murder is murder is murder. but……..

Next day you see the boss on the news “Well yeah, we fired him 36 hours before the killings, so……” and the guy that got fired killed Diego, the building janitor. What did Diego have to do with your boss firing you??

“Should we take some kind of solace in the fact it wasn’t random?? ”

What I ask myself every time. No person of any country should have to ask this this many times.

Finally, a call for democracy in China.

Property rights are the key to progress. Without them, there will be insufficient investment in physical, institutional, and human capital at some point. This is the problem in Russia, and more recently, in Hungary. If you build a business big enough, someone will notice and take it away from you. Therefore, entrepreneurs relocate out of those countries when their businesses grow large enough and never undertake certain kinds of investments at all.

Back in the early 1990s, I had dinner with Bill Browder in Budapest before he left for Russia to found Hermitage Capital. He said he would focus on extractive industries, which he did. I was amazed though, because Hungarians were deathly afraid of Russia: You can keep your business are long as the politics there let you. When Hermitage grew large enough, Putin decided to take it away from Browder, which he did, including the imprisonment, torture and killing of Sergei Magnitsky. This was all obvious and pre-determined before Browder ever set foot on Russian soil. I thought Browder was both incredibly smart and incredibly naïve. I still do.

In Russia, as in China, property rights exist at the whim of the dictator. Xi can take anything away from anyone. If that’s the case, then at some point investment will slow, and those who can will leave the country with their businesses.

By the way, war is the key form of expropriation. Look at all the businesses and entrepreneurs expropriated by Russia as a practical matter as a result of the war. It is two or three orders of magnitude greater than anything done to individual businessmen. So who started the war? The Russian people? Well, they’ve lined up with the effort ex-post, but there was no public agitation to start a war in Ukraine. All this was because of one man, and one man alone: Putin.

Now imagine that Russia was a proper democracy and Putin had to stand for election knowing that he sent 30,000 boys to their death. Would he have started the war? I sincerely doubt it.

And that brings us full circle to Xi. If China invades Taiwan, then the expropriation seen in Russia will also occur in China. Companies will lose their export markets and commodity suppliers; only sons will lose their lives; many people will lose their jobs and livelihoods; and China will lose its place in the world for a long time. And that’s if China wins the war. And why is that good for China? It’s not. Are the Chinese people agitating for war with the US and the western world? I don’t see it. I see a lot of hard working, aspiring middle class people looking for a better job, better housing, and good education for their children. A war serves Xi’s ego, but for China — as for the rest of us — it would be an abject disaster.

The best protection of property rights over the long run is democracy, where property rights are held by law rather than by power, and where that law answers to the public, not to an oligarchy or autocrat. That’s why there are no advanced economies (except oil exporters) which are anything but democracies. Democracy is the political mirror of an advanced economy, because an economy cannot become advanced without the protection of property rights through the rule of law.

As I have said before, barring a nuclear war, China will be a democracy by 2026.

I agree with everything except the last line. That one’s straight out of left field!

It’s straight off the graph, assuming China continues to grow. There is no precedent for a country which is not an oil exporter to reach China’s forecast GDP / capita without becoming a democracy. The economics at that point will no longer support the current political structure. Property rights will be the point in question.

I think much depends on how the Li / Xi power struggle, now well underway, turns out. Xi will take China into war with the US, one which will be devastating for the entire planet. Li will turn China towards democracy. He is a very, very smart guy and he will be rightly consumed with preventing another dictatorship from arising in China. Sooner or later that will take the Chinese leadership through the Federalist Papers, and they will come to the same conclusion Hamilton did.

China is large, but China and the Chinese are not special. They are like the other industrious — and even not so industrious — nations of East Asia, that is, like the Koreans, the Taiwanese, and the Japanese. All of them became democracies by the time they crossed the GDP / capita threshold equal to where China will be in 2026. Underneath the political rancor of Xi is a wonderful country rapidly entering becoming middle class. Xi may yet destroy China as Putin has destroyed Russia, but the Chinese are smart people, and cooler heads may prevail. If they do, China will be a democracy by 2026.

I stand by my forecast.

I’d love you to be right, but the Koreans, Taiwanese and Japanese didn’t have or had long shed their totalitarian governments of the past. Xi seems to be moving backwards. It’s scary totalitarianism now, complete with massive prison camps for ethnic minorities – and it can get worse.

And one thing that often happens to fast-growing, middle-income countries is that they stop growing, because once they’ve built up the capital stock, they can’t squeeze any more growth out of their economy because that would require innovation. Innovation’s hard with the government breathing down your neck.

Again, I’d love it if you’re right, but your prediction sounds like a take from some journalist selling a book.

Read the graph, report the graph. I’m telling you what the graph is telling me.

But let me be clear about this: The Chinese are not special. They are not inherently inferior to those above-mentioned Japanese, Koreans and Taiwanese. By no means. The assumption that somehow the Chinese do not merit rule of law or a normal society is categorically wrong to my mind. Take that ‘*’ away from China and put them in the same hat as the other three mentioned countries.

Now, Xi may start a war and trash us all. Certainly possible. But if the country is allowed to breathe and develop, it will start looking more like Taiwan in just a few years.

Steve,

“Read the graph, report the graph” isn’t a model. This isn’t how we make predictions about huge issues like when a country becomes a democracy. Instead, it’s a way lazy journalists turn hot takes into best-sellers.

“The Chinese are not special.” Didn’t say they were. These are four geographically co-located countries, three of which were similarly poor mid-century. But there are important differences. Totalitarian communism is one of them. I don’t have the answer, I’m just suggesting there are big problems with your method.

Again, I think you have the right general idea about the importance of good institutions. And I’d love it if you were right about China. Would be one of the great moments in human history. But I don’t see where your confidence in your prediction comes from.

Andrew,

You’re begging the question of what is a model. To my mind, a model frames some correlation between two or more variables and permits the forecasting of events based upon the independent variable. The relationship need not be strictly causal, but there has to be a correlation, some if-then relationship.

The model I have developed has more than that. You can even run a linear regression on it if you like. And the relationship is pretty stark. See the graph: China’s Governance Options. https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2018/4/8/chinas-governance-options

I have updated, but not published, the associated graph, but the conclusions are largely similar.

All models are simplifications, so is this one. But we actually have some causality to discuss, and that’s the need for articulated property rights. I do not think China today is politically stable. It must either regress into a closed society, or it must transition to democracy. Historically it has always done the former.

This is the same thesis as that of Roger Garside in China Coup

“China’s leader Xi Jinping will very soon be removed from office in a coup d’état mounted by rivals in the top leadership. The leaders of the coup will then end China’s one-party dictatorship and launch a transition to democracy and the rule of law.”

Note that this is different than Tiananmen Square in 1989. This is a civil war within the Party, one which I believe has already begun. If there is to be a new Tiananmen Square, it will be the Li faction facing off against the tanks. Putin has driven home to China’s reform leadership (for lack of a better name, the historic Deng faction) that an ego-driven dictator can destroy everything China has achieved since 1976 — including the Communist Party!

So, China will have to choose — and soon — between growth and autocracy. It can remain an autocracy at the cost of growth; or it can transition to a democracy and maintain growth. But it cannot do both for much longer.

Btw, I have said that there are three things that could bring down Xi: a financial crisis, an oil shock, or a war. We are now facing an oil shock, all thanks to EU leadership. Let’s see how Xi does.

It was “common wisdom” among post-WWII policy pundits that countries which trade don’t go to war with each other. Not true. Now, you claim to have a rule about democracy and GDP per capita. Lots of luck.

This site hasn’t been updated in a long time, but it still make its point:

https://www.tylervigen.com/spurious-correlations

I recommend it to anyone who thinks they’ve discovered an unassailable regularity in the world. I would also recommend the work of Philip Tetlock when it comes to claims of expertise.

“It was “common wisdom” among post-WWII policy pundits that countries which trade don’t go to war with each other.”

Did I say that? I doubt it. World War I was a great case of trading partners going to war with each other. Anyone who knows a bit of economic history knows that trade as a share of GDP did not regain its pre-WWI levels until the 1970s.

See Figure 3 World exports, 1870-2010

https://www.sfu.ca/~djacks/research/publications/The%20First%20Great%20Trade%20Collapse.pdf

Also, your model didn’t predict Hungary’s becoming authoritarian. I bet you also wouldn’t predict the US following Hungary’s footsteps, but anyone familiar with the names Trump and DeSantis should be worried. CPAC was in Budapest this year, first time ever outside of the US.

Actually, the Three Ideology Model is consistent with the rise of a kind of authoritarianism. I stated that the fiscal conservatives — the classical liberals — had been pushed back to the left of the median voter boundary by the collapse of communism. This brought the traditional conservatives — the social conservatives — to the median voter boundary, making social conservatism an “active” ideology (that is, the ideologies to the immediate left and right of the median voter boundary will tend to define politically viable policy).

Conservatives feel comfortable in hierarchy, and they defer to leadership to do the thinking. At the same time, leadership may perceive such conservatives as sheep to be exploited. That pretty much sums up Russia, doesn’t it?

In any event, the importance of Orban and Fidesz is that the phenomenon is not limited to Hungary. Putin, Xi, Trump, Erdogan and a few others fall into a pretty similar mold. So we are talking about a global phenomenon, not a national or regional one, and therefore the driver must be similarly global.

I don’t think I appreciated at the time how dangerous this could be. The traditional left — the liberals and egalitarians — have always looked upon hierarchical conservatism with great suspicion. We see now that this fear may not be entirely misplaced. With social conservatives in control, one man, and one man alone, can plunge the world into darkness. Conservatism on the median voter boundary can present simply extraordinary systemic risk in a way that communism, strangely enough, did not. The US and Soviet Union were locked in a Cold War for 45 years, and yet neither side was willing to directly challenge the other and both were very careful about nuclear weapons after 1962.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the communist era, this nuclear taboo has been abandoned by both the Russians and the Chinese, as though fighting a nuclear war were some sort of viable option. And why is that? Because these countries are each now run by one man whose ego dominates other considerations. That, unfortunately, appears to be an undesirable facet of conservatism.

In any event, I don’t think I have adequately answered your question, but that’s what I have for the moment.

https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2021/12/18/where-do-the-moderates-belong

https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2022/2/20/a-note-to-my-new-readers

“The Chinese are not special. They are not inherently inferior to those above-mentioned Japanese, Koreans and Taiwanese.”

Wow Chief, thanks for clearing up that perennial debate that has been dogging the stinkier sections of New Jersey for decades.

This, the “consultant” says, who after THOUSANDS of brown people died in Puerto Rico said (my paraphrase) “Excess deaths of brown people?? What excess deaths of brown people?? I don’t see anything, do you?? Oh I have an in-law who is Korean, don’t start this racist stuff with ME”

He’s an entertaining little fruitcake, isn’t he??

Whatever Stevie is betting on Fan Duel – bet the opposite. You will be rich!

I would not bet on these sites.

“A recent study of daily fantasy sports sites revealed that 91% of all profits won went to just 1.3% of players. What’s more, 85% of all players on daily fantasy sports players were losers.

“How is this possible? It turns out that there’s a tiny percentage of FanDuel and DraftKings players who are using sophisticated algorithms to help them draft consistently superior teams. In fact, some daily fantasy sports players are essentially professional gamblers who spend hours a day tinkering with homemade algorithms designed to give them an edge over all the other suckers who are just picking players using their gut instincts.”

https://bgr.com/general/john-oliver-fanduel-draftkings-video/

I hesitate to get into this, something I have published on . I guess I shall applaud the authors for getting a top publication, and I get that probably their analysis of their data is reasonable. I guess I am not all that surprised by these results, but would warn that these may not hold more generally. I suspect they especially hold for this period with this data set.

What has me bothered here? Well, the big one is this meme about legal origins, which, frankly, has really serious problems and has been substantially discredited as a general argument, although it has gotten itself embedded into lots of textbooks and general discussions. But I would note here that it might not be surprising that one might find a data set drawn from British data during a period of British dominance would find that financial outcomes look better in places with a British legal system.

Anyway, I would say that most of the commentators here are making way too much more out of this study than is in it, although it is competently done. Oh, and, yes, of course, security of property rights is helpful to economic growth, but it is far from generally clear that more broadly that is as closely tied to having a British style common law system than these authors and some others claim. This is not nearly as correct in general as many have claimed.

This doesn’t have any connection to Paul Krugman not giving you any personal credit for his Nobel Prize, does it??

Barkley Rosser:

Please see my reply to AndrewG above, which addresses some of the points you raise about the conceptual problems with measures of legal origins.

Although we find some evidence that countries with English legal origins paid a lower cost of equity capital, the paper’s most robust and consistent evidence comes from the regressions that use European settler mortality. This conclusion is subject to the caveats about using such measures in the first place. In response, I point you to my arguments in my reply to AndrewG. We used several different measures of institutional quality, including ones from the modern period, and reported the regression results based on all of them.

One way to interpret our findings is that British investors in the late 19th century preferred to invest in countries with a legal system similar to their own, subject to the qualification that the legal origin dummy does not capture all the complexities of a legal system. This conclusion is broadly consistent with the so-called Empire Effect in sovereign debt markets of that period — the idea that British colonies could borrow on the international capital market at favorable rates because of an implicit guarantee by the British government. Keynes remarked on this phenomenon, and Ferguson and Schularick found quantitative evidence in favor of it in a Journal of Economic History paper.

It will not surprise you that the English common law indicator correlates highly with a dummy variable for being a British colony. Therefore, you can view this finding for equity risk premia as analogous to the Empire Effect. However, the economic reason for equities differs from the sovereign Empire Effect. Rather than being related to the implicit British guarantee for British foreign investments, which we show did not exist, it is related to the similarity between legal systems. To the best of our knowledge, no one has documented this Empire-like effect in equity returns.

Stepping back, however, it is important not to push this interpretation too far, given the evidence. Our findings are less consistent for legal origins than for settler mortality. The regression and qualitative evidence from 19th and early 20th-century investment manuals point to the conclusion that British investors valued property-rights institutions. There is similar evidence using the legal origins data, but it is less robust.

In the end, we are left with the classic “on the one hand, on the other hand” problem that plagues economists and the economics profession generally. But the available evidence can only bear so much weight, and we need to be frank about what it supports and does not support.

Ron,

Glad to see you are more cautious about the legal origins part of your argument. Hard fact is there has been way too many baseless claims about hos pro free market English common law is compared to say the Napoleonic civil code, much less all those intermediate forms like the German and Scandinavian. Gordon Tullock of all people argued that actually the Napoleonic code more clearly defends property rights than does English common law. I could say a lot more on this and have in print, but I do not want to get somebody here too worked up thinking that somehow this has something to do with Paul Krugman, which it certainly does not.

Oh, but Tullock did not get a Nobel, and he should have.

Ron (et al),

You can find my detailed analysis of the legal origins theory in “A Critique of the New Comparative Economics,” coauthored by me and Marina V. Rosser, which appeared in 2008 in the Review of Austrian Economics. You can access a version of it on my website at http://cob.jmu.edu/rosserjb .

I note that the main advocate of the argument that English common law is strongly tied to positive free market outcomes has been Andrei Schleifer, who strongly pushed this argument when he was editor of the QJE in which a bunch of the papers by him and various coauthors appeared. I note that most of the advocates of the theory are economists. I note that most of the serious critics are people with law degrees, some of them cited in the paper I noted above. I also note that the late Gordon Tullock’s degree was also in law, not economics.

Sorry, “Shleifer,” not “Schleifer.” A lot more could be said about him here, but it is not really relevant to all this, although arguably somewhat ironic.

Barkley:

We were unaware of your paper and Tullock’s specific argument about the Napoleonic code, though we did know about other criticisms of the conceptual basis for legal origins. Thanks for pointing us to your work.

Thorsten Beck also has an assessment of some of the problems with legal origins in a 2012 survey paper on the topic. He makes a point similar to yours. Historical research on legal origins indicates that legal institutions are not as persistent as is commonly assumed. Specifically, some French civil code countries had as strong creditor rights as common law countries in the early 20th century but the opposite is true now.

https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195391176.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195391176-e-3

There are evidently sound reasons to be concerned about measurement error associated with the legal origins dummies. For this reason, we tried to be appropriately balanced in drawing general conclusions based on the legal origins data and acknowledged where we had obtained the strongest evidence.

Ron

– are the less than 0.5 r2 in Tab 3 and even zero r2 in Tab 1 enough to make conclusion on dependancies?

– how do you explain the difference in settlers death rates between countries? what was the settlers death rates compared to indigenous population death rates?

– what was the indigenous population death rates and how it correlates with the alpha and capital flows?

– what was the per capita income in sample countries? and how it correlates with rate of return and risks? Is it institutions or just different stages of development?

– what was the resource endowment of sample countries?

– how the global commodity price volatility affected alpha?

– which sectors of economy are represented by the data sample? is not it a comparison of returns and risks across different industries ?

– what was the difference in interest rates and inflation between countries?

– why economic factors are not considered?

– Figure 1 – removing of couple countries will eliminate the “correlation”. How do you explain the big group of countries where the same settler death rates and alphas correspond to quite different ricks of expropriation?

Good questions. About low R-sq, it just means many other factors not considered in the model are more important. Note, though, that when they throw in the geographic controls, the r-sq goes up to 0.4, which is pretty good for the social sciences. That model explains a lot of variation.

About your other questions (indigenous mortality, factor endowments, etc), here’s something to read:

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (2016). The European origins of economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(3), 225-257.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10887-016-9130-y

Ungated: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w18162/w18162.pdf

Misha:

We answer many of your questions in the paper, the link for which is above. Here are some responses to a subset of your questions.

1. The low R-squareds are not surprising given that the regression sare based on individual equity returns, which are noisy. The R-squareds are higher for the country portfolios because they mitigate the noise of individual equity returns.

2. Acemoglu et al. (2001) discuss the differences in settler mortality rates. Albouy (2012) is the most influential criticism of using settler mortality. Both references are in the paper.

3. We discuss the measure of resource endowments in the paper and appendix. They are from Clemens and Williamson (2004).

4. The industries represented in the sample are in a table in the paper. In general, they are industries associated with infrastructure and primary commodity exports (e.g., railroads, mines, and ranches, among other industries). This evidence supports the prevailing view of the projects that British capital financed during that historical period. See, for example, Fishlow (1985), which we also cite in the paper.

5. On interest rate and inflation differentials: We compute the risk-adjusted cost of capital, which estimates the rate of return on investments in that country. Inflation rates differed but were generally low during this period because many countries adhered to the gold standard. Our results are not sensitive to controlling for gold standard adherence. For more on this point, see Alquist and Chabot (2011).

6. We consider economic and geographic factors. See the paper.