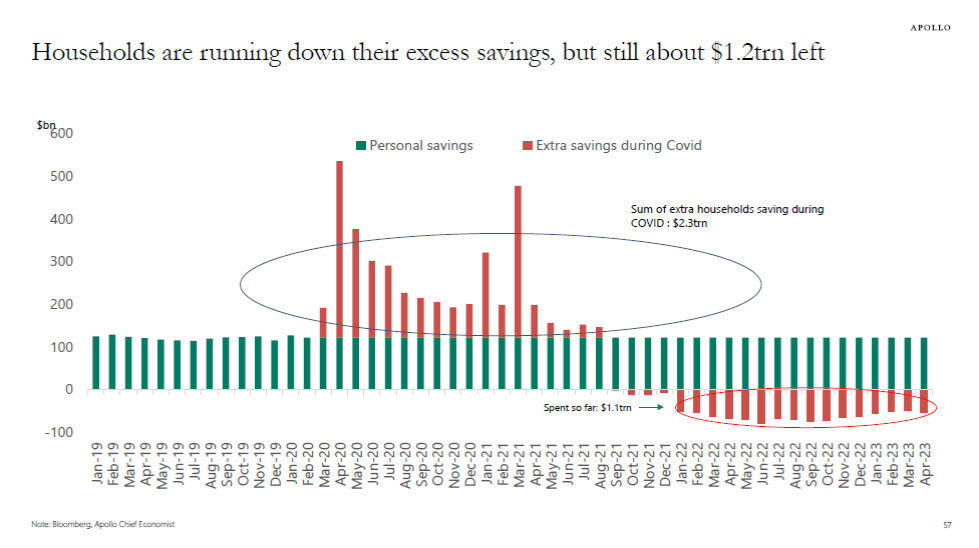

The permanent income hypothesis in its RatEx-no liquidity constraint version says that consumption will adjust upward fully in response to a windfall. This will mean it will take a while to decumulate the “excess savings” transferred during the pandemic. How much remains? Here’s a guess from Torsten Slok:

Source: Torsten Slok, Apollo Advisers, June 5, 2023.

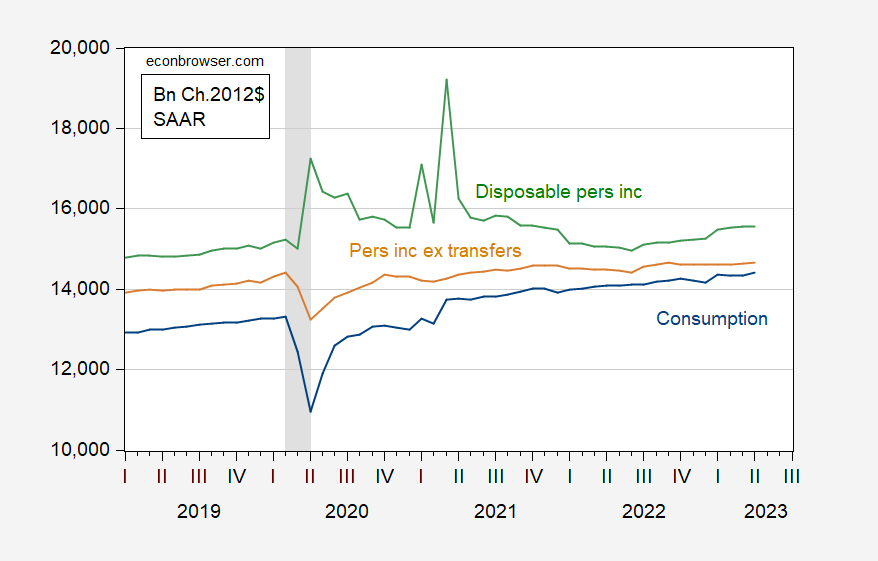

Another way to look at this is to look at the flow of income and consumption (in real terms):

Figure 1: Consumption (blue), personal income ex-transfers (tan), and disposable personal income (green), in billions Ch.2012$ SAAR. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, NBER.

Priced-in odds for next week’s FOMC rate decision are 2-to1 for no rate hike. A bit of context from our smoldering northern neighbor – the BOC just resumed rate hikes after a two-meeting pause.

If Canadians would just learn to shit all over their own citizens/consumers like America does, maybe they could learn the advantages of corporate profiteering, or what Larry Summers and our greatest orthodox economists (orthodox economists read as corporate lap dogs) refer to as “wage and employment created inflation”. These are proud times for the profession.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health/canadians-live-longer-healthier-than-americans-study-idUSTRE63R6B520100429

Canadians just have to learn to build inferior products that break when you look askew at them, and write laws which don’t punish manufacturing products that kill people. Give the Canadians time, they’ll learn from America’s great example.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/07/business/economy/debt-ceiling-borrowing-binge.html

June 7, 2023

A $1 Trillion Borrowing Binge Looms After Debt Limit Standoff

The government has avoided default, but the effects of the debt-ceiling brinkmanship may still ripple across the economy.

By Alan Rappeport and Joe Rennison

The United States narrowly avoided a default when President Biden signed legislation on Saturday that allowed the Treasury Department, which was perilously close to running out of cash, permission to borrow more money to pay the nation’s bills.

Now, the Treasury is starting to build up its reserves, and the coming borrowing binge could present complications that rattle the economy.

The government is expected to borrow around $1 trillion by the end of September, according to estimates by multiple banks. That steady state of borrowing is set to pull cash from banks and other lenders into Treasury securities, draining money from the financial system and amplifying the pressure on already stressed regional lenders.

To lure investors to lend such huge amounts to the government, the Treasury faces rising interest costs. Given how many other financial assets are tied to the rate on Treasuries, higher borrowing costs for the government also raise costs for banks, companies and other borrowers, and could create a similar effect to roughly one or two quarter-point rate increases from the Federal Reserve, analysts have warned.

“The root cause is still very much the whole debt ceiling standoff,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, an interest rate strategist at TD Securities….

This is a really interesting approach, in effect, highlighting a wealth effect as a key driver of sustained consumption. Balance sheet, not income statement, is driving things for the moment.

Steven Kopits: It’s basic macro, like I learned in undergrad.

Right, but I think Fig.1 implies that this is a transient wealth effect likely to last maybe another year. This would appear to be one explanation of why no recession so far (aside from a fiscal correction in H1 2022). That is, there’s still a lot of money sloshing around the system, not because incomes have grown that much, but because the public still has a lot of excess savings from the pandemic era. So sometime around 2025 we find out where we really stand.

transient?

Do you have even the remotest clue what “Life Cycle” even means? Or have you taken the time to READ Robert Hall’s 1978 paper? Didn’t think so.

Accounting? Dude – Milton Friedman would not agree. Nor would Ando & Modigliani. The model considers not just wealth accumulated from the past but also expected future lifetime income. But you would not get that as you never learned either economics or basic finance. Try doing so before making another uninformed comment.

“The permanent income hypothesis in its RatEx-no liquidity constraint version” aka Milton Friedman’s consumption model.

Doesn’t this model lead to similar results?

The “Life Cycle” Hypothesis of Saving: Aggregate Implications and Tests

Albert Ando and Franco Modigliani

The American Economic Review (1963)

pgl: The Hall version of the PIH has a slightly different implication than Friedman’s original model. The Ando-Modigliani version incorporates (as I understand it) liquidity constraints, so there are no ways to differentiate between the particular versions.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/260724

Robert Hall (1978)

Stochastic Implications of the Life Cycle-Permanent Income Hypothesis: Theory and Evidence

OK – we did have to read this in graduate school. Thanks for reminding me!

I’m curious how much (percentage) of the supposed “$1.2 trillion” in disposable saving is being held by, say, people with a yearly income of over $400k~~i.e. Money that will not be spent for a long time. Because I frankly find that number astoundingly difficult to believe when American credit card debts are rising very quickly. Why would credit card debts be rising drastically if people still have savings to use?? It strongly implicates the $1.2 trillion number as a lie. And I like Slok, but the two numbers held up against one another make zero logic at all.

It’s nice cover/Three-card Monte for economists who can’t face the fact the inflation is not “demand created” but in fact corporate profiteering. So, that must make them feel good about themselves as tools for corporate screwing over of consumers.