That’ s leading question in the NYT a little while back (just getting to this now that I’ve finished grading).

America’s contemporary economy, Mr. Rieder argued in his note to clients, is less vulnerable to the boom-and-bust cycles of old — mainly because its prosperous consumers are service-oriented, less dependent than ever on factories or farms. Consumption spending makes up about 70 percent of the economy.

In one sense, it’s indisputable that the business cycle is less pronounced, if one looks to the time series properties of real GDP.

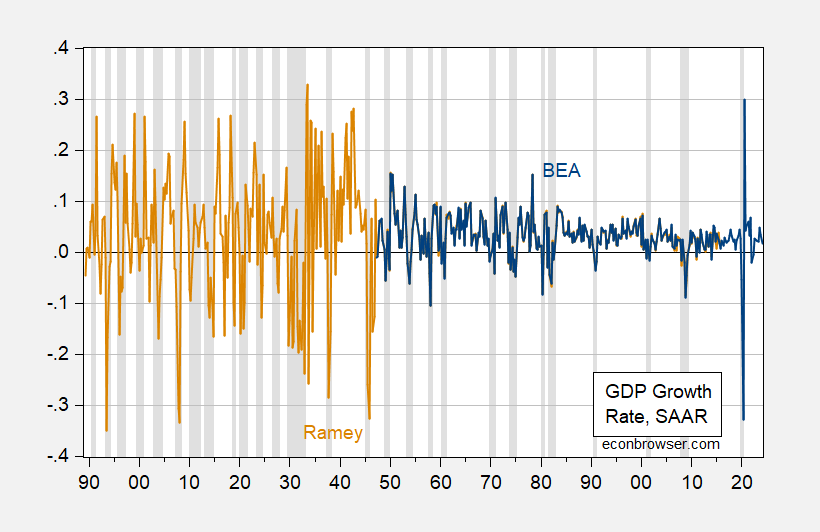

Figure 1: Quarter-on-Quarter annualized GDP growth rate from BEA (blue), from Ramey (tan), calculated in log differences. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, Ramey, NBER and author’s calculations.

Even for the sample compiled by BEA, one has the following picture of generally declining volatility in GDP.

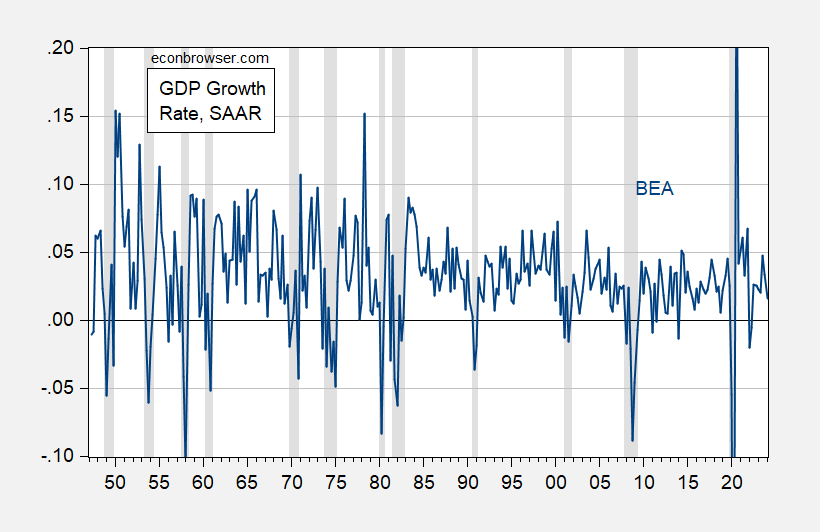

Figure 2: Quarter-on-Quarter annualized GDP growth rate from BEA (blue), calculated in log differences. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, NBER and author’s calculations.

Aside from the pandemic related recession, GDP volatility has been much smaller. The length of expansions as determined by NBER has also increased. This change has been apparent for a long time, and prompted Bernanke’s coining of the term “the Great Moderation”.

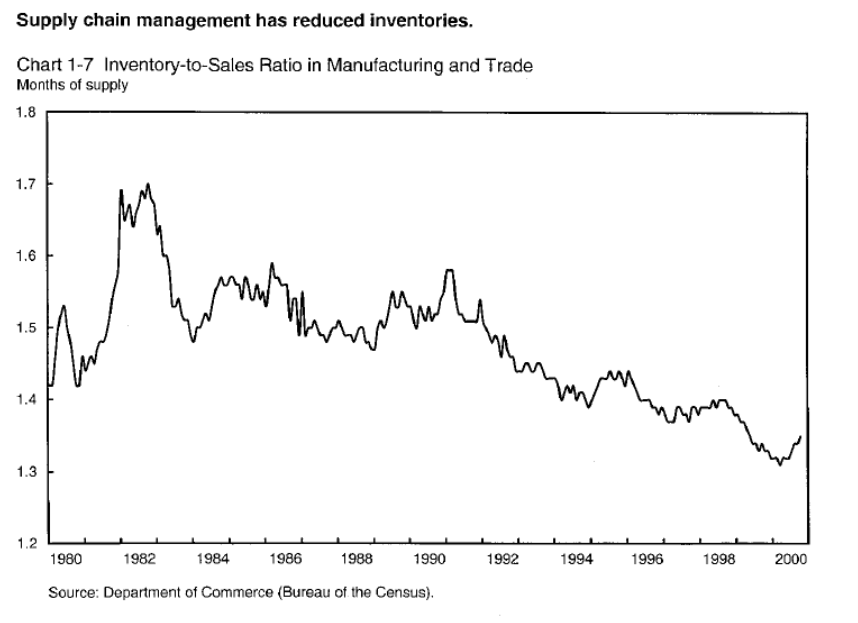

The discussion reminds me of the talk around the turn of this century about how new information technologies would allow for enhanced inventory management (Economic Report of the President, 2001):

The new information technologies have also changed the nature of relationships between firms and their suppliers. Procurement practices have changed radically, as firms become linked to suppliers through Internet-based business-to-business marketplaces. This capability allows businesses to streamline procurement activities, lower transactions costs, improve the management of supplier relationships, and even engage in collaborative product design. “Just-in-time” delivery, facilitated by a more efficient transportation network including both surface and aviation infrastructure, has been instrumental in allowing firms to reduce inventories and lower costs while continuing to provide essential services to producers and consumers.

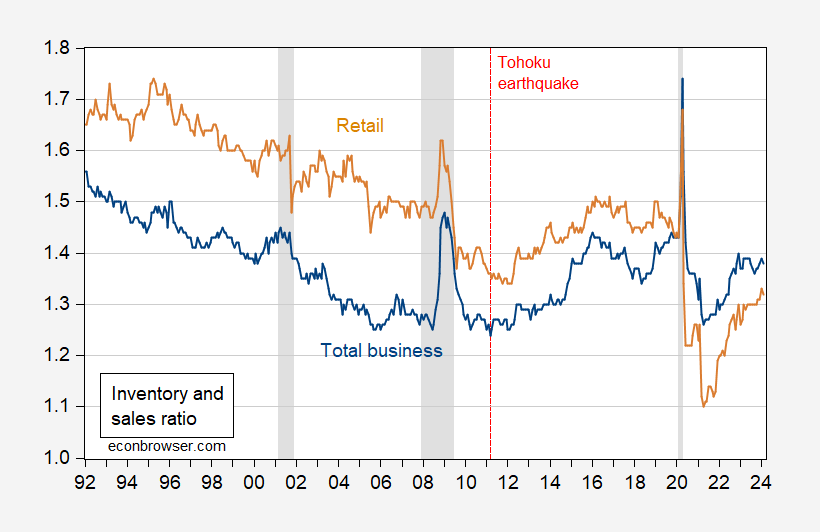

I don’t have access to the same series, but here are inventory-sales ratio for total business and for retail, with sample extending to 2023Q4.

Figure 3: Inventory-to-sales ratio for total business (blue), for retail (tan). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: Census via FRED.

Inventory ratios continue to shrink after 2000, until 2008 when interrupted by the Great Recession. They start to rise again after the Tohoku earthquake in Japan, which highlighted the hazards of far flung supply chains.

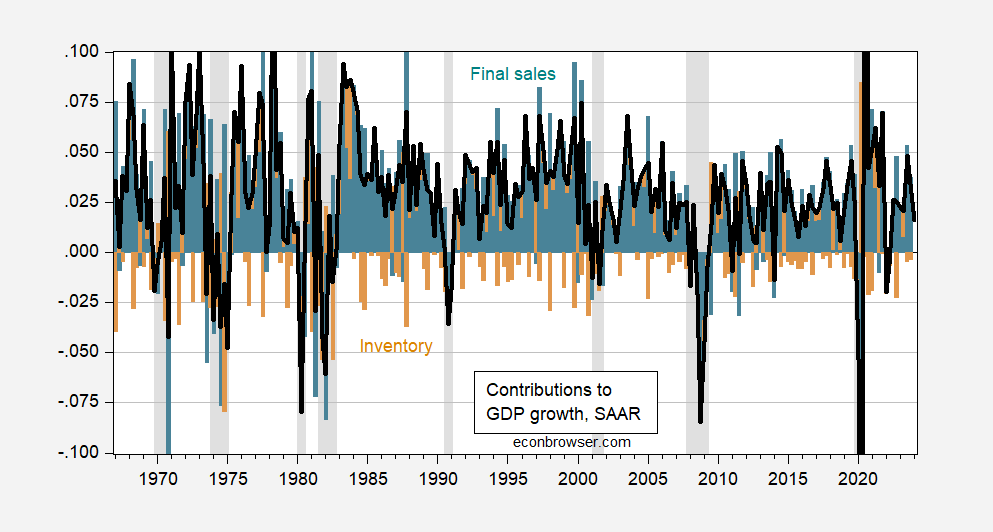

What does seem true is that the relative contribution of inventory changes to overall GDP growth has declined over time.

Figure 4: GDP q/q annualized growth rate (black line), contribution of final sales (teal bar), contribution of inventory changes (tan bar). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA.

So, to some extent, the story that we tell in intro macro about disequilibrium in the Keynesian cross being eliminated by inventory decumulation or accumulation via production changes is less relevant than in the past. Whether that remains true depends on the extent of re-shoring, or friendshoring, as countries and firms attempt to shock-proof supply chains.

As noted in the NYT article, however, other shocks — demand and supply — remain, including financial crises (2007-09), debt crises (2009-12) or pandemics (2020). For me, the business cycle remains, even as some propagation modes might have become less relevant.

Roger Stone Blasted For Claiming ’90s Concert Photo Was Actually Trump Rally

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/roger-stone-blasted-for-claiming-90s-concert-photo-was-actually-trump-rally/ar-BB1mjYge?ocid=msedgdhp&pc=U531&cvid=993723038a3b409bbbd874b112de6ae7&ei=11

Wildwood NJ in 2024 or Copacabana Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1994. No difference when one is as drunk as Roger Stone!

Please don’t berate imbibers by putting them in he same cluster as Roger Stone. Roger’s idiocy/bigotry is inherent to his character, not because being zonked by adult drinks.

I’d also say that information technology has made the “bullwhip effect” less of an inventory management problem. The “bullwhip effect” is due to each supply echelon (e.g., top level wholesale, intermediate retail, etc.) pursuing uncoordinated resupply policies that result in boom/bust inventory levels. Information technology allows suppliers to coordinate resupply actions and react to point-of-final-sale demands rather than just demands from lower supply echelons.

Another way to assess variability in business cycles is to look at employment. Here’s the quarterly % change in both goods and services employment:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1nW4P

Other than around the Covid recession, goods employment is more variable than service employment. You can clearly see the Great Moderation in the figure. The amplitude of employment swings declined on the upside during the Great Moderation, both directions for services, but maybe not on the downside for goods. Housing is a good and supply chain interruptions hit goods, so we are beset by special cases here.

Amplitude isn’t the only factor in variability. Frequency of recession is way down, too.

Since the share of service production in output has risen over time, services do seem likely to be an explanatory factor in the reduced variability of output. How does the rise of services compare with the decline of inventories in reducing output swings? Dunno.

Indebtedness “should” exacerbate cyclical swings, and surely did in both the Japanese real estate crash and during the Great Recession, with real estate bubbles a feature of both, but does indebtedness regularly exacerbate recessions? Overall indebtedness has actually risen during the period of less frequent recessions, so on the face of it, debt doesn’t look like a persistent cause of increased variability.

Somewhat on topic.

We have had concern expressed about corporate greed causing inflation.

Reuters has posted an item from SF Reserve Bank disagreeing with corporate greed being the cause of increasing inflation.

Reuters Article

https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/corporate-greed-not-blame-price-pressures-fed-study-shows-2024-05-13/

FSBSF Article

https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/2024/05/are-markups-driving-ups-and-downs-of-inflation/

Somewhat similar conclusion, if I read it correctly.

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2023/06/inflation-a-decomposition

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1nW9S

I think one thing that plays into the perception of corporate greed is that corporations don’t like to change prices frequently – we (very, very large retailer) try not to do so more than once a year for any item – and, consequently, when input prices start increasing, and it looks like it will persist – as with the supply-chain driven difficulties of the last few years – we try to get ahead of the next 6 – 9 months of cost increases. This leads to price increases that can be significantly larger than necessary to catch up with the recent history of cost increases, which looks like opportunistic price gouging but really isn’t.

Here’s a link to a history of quarterly Walmart profit margins: https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/WMT/walmart/profit-margins. As you can see, there hasn’t been a single quarter in 2021 – current with a profit margin as high as the lowest quarter in the 2010 – 2017H1 period. If Walmart, for example, were price gouging, it certainly didn’t seem to be doing a good job of it.

On the other hand:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/W273RE1A156NBEA

Different accounting systems yield different results, of course. In GDP accounting, there is an upward trend in profits as a share of output since the mid-1990s. A period of historically high profits as a share of GDP commenced after the Great Recession.

Profit maximization is, after all, a feduciary requirement of public companies. Call it what you will, but squeezing profit out of commerce is what business exists to do.

This is an outstanding (but long) article of how Wall Street took over Hollywood and screwed everybody there – including themselves (in a yet to come sequel).

https://harpers.org/archive/2024/05/the-life-and-death-of-hollywood-daniel-bessner/

There is a lot of golden nuggets about how the standard predatory capitalism model of “Takeover – Efficiency – Monopoly – Extraction” has changed entertainment. But be ready for a sad ending. I don’t see how they can avoid killing the golden goose. Young people are migrating towards social media in part because the canned products just aren’t that good and who want to eat the same soup warmed over for the 50’th time. We all know how a good thing is good, until it’s not.

One thing that was a new insight to me was how they had turned the writers into gig workers who had to have side jobs to survive. Those people can strike forever if you piss them off badly. They just increase their income from side jobs. So, corporates cannot just hold out and brake striking gig workers. The corporates, who are held to quarterly profits, are on a much shorter timeline for ending strikes.