Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Mark Copelovitch (Political Science and La Follette School, University of Wisconsin – Madison) and Michael Wagner (Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin – Madison).

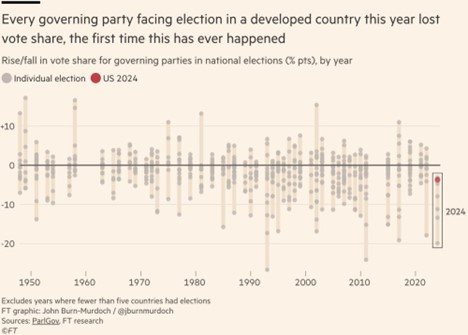

Last week, John Burns-Murdoch of the Financial Times documented the anti-incumbent backlash in 2024 across the developed world. Donald Trump’s victory over Vice President Kamala Harris is quite clearly part of this broader international trend.

Burns-Murdoch linked Trump’s victory primarily to inflation: “Voters don’t like high prices, so they punished the Democrats for being in charge when inflation hit.” This has quickly become the conventional wisdom about the US election. We are skeptical of this claim, and our research suggests we should avoid rushing to such conclusions. Our evidence suggests that voters’ anger is most closely related to what they are hearing about inflation from news sources. Even when we examine what people know about inflation and, indeed, what they are experiencing in the economy itself, it is hearing about the terrible economy, rather than living in the decent one, that seems to be driving voter behavior.

Through YouGov, we conducted surveys, from October 30 to November 4, in the US and Germany, in which we asked 2000 individuals in each country about their views on inflation, the economy, and politics. Our results strongly support the anti-incumbent backlash argument. In the US, only 29.9% of respondents approve (9.6% “strongly”) of President Joe Biden, while 54.3% disapprove (41.0% “strongly”). In Germany, Chancellor Olaf Scholz is even more unpopular: only 15.4% approve (2.4% “strongly”) of his performance, while 60% disapprove (a staggering 36.4% “strongly”).

But anger at incumbents does not appear to be driven by anger about inflation and the economy – at least if we mean this in material terms. To be sure, an overwhelming share of those in our surveys were concerned about inflation. On a 5-point scale, 62.9% of German respondents were “concerned” or “very concerned” about inflation, and 59.5% thought it was a “big” or “very big” problem for themselves and their families. In the US, these numbers were even higher: 76.1% and 67.1%.Yet when asked about their personal financial situation, few said they or their family are struggling (22.1% in the US, only 12.3% in Germany). In fact, more said they are living comfortably (26.7% in the US, 36.6% Germany), and there is only a modest correlation in the US between family financial situation and whether people think inflation is a problem or approe of President Biden. The link between inflation concern and Biden approval is a bit higher, but that suggests a lot of those concerned about inflation are not really feeling material hardship from it. Germany looks similar: the correlation between approval of Olaf Scholz and whether one thinks inflation is a personal/family problem is extremely low.

Moreover, when we asked individuals if and how they could pay an unexpected bill of either 500, 2000, or4000 dollars (euros), their most common answer was that they would be able to pay from cash savings (34.7% in US, 57.3% in Germany) or credit (33.1% in US, 18.9% in Germany), while far fewer said they would not be able to pay (19.3% in US, 12.4% in Germany) at all.. Voters may be angry about inflation and the economy, but they simply do not report being worse off materially than four years ago.

Nonetheless, both Americans and Germans are deeply pessimistic about the economy. 52.4% of our US respondents (and 72.6% of Germans) think the economy has gotten worse in the last year. Even more shockingly, more American respondents (39.6%) think the US is currently in recession than not (37.5%), despite 4.1% unemployment and 45 consecutive months of job growth. The German economy is actually a mess: he country is in recession and real wages and income remain below 2019 levels. But the US economy is booming, and most Americans are better off on almost every metric (wages, income, consumption), than four years ago, even controlling for inflation.

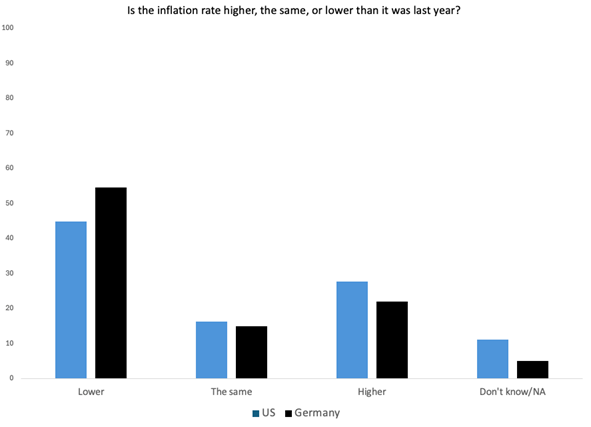

So is this an information problem? Well, it is not a factual information problem. Most people know actual prices. We asked our survey respondents about the price of gas, milk, and the national inflation rate, and they overwhelmingly answered correctly, within tiny margins. It does not appear to be the case that individuals are not aware of actual prices, such as the fact that gas now costs nearly $2 less per gallon in the US than it did in 2022, or the fact that US milk prices are 5% lower than two years ago.

And yet, despite having a clear grasp of real prices, about one quarter of respondents in both countries said inflation is higher now than a year ago.

Most Americans and Germans seem to think the economy is terrible and getting worse, despite their personal situation being fine. Many think inflation is rising, despite knowing the actual price of milk and gasoline. And, most notably, they think opposition parties understand their concerns better than incumbents: in the US, 38.9% of those we surveyed said that the Democrats think inflation is a “big” or “very big” problem on a 5-point scale, while 71.4% said the same of the Republicans. In Germany, these numbers for the SPD and AfD, respectively, were 44.5% vs 52.4%.

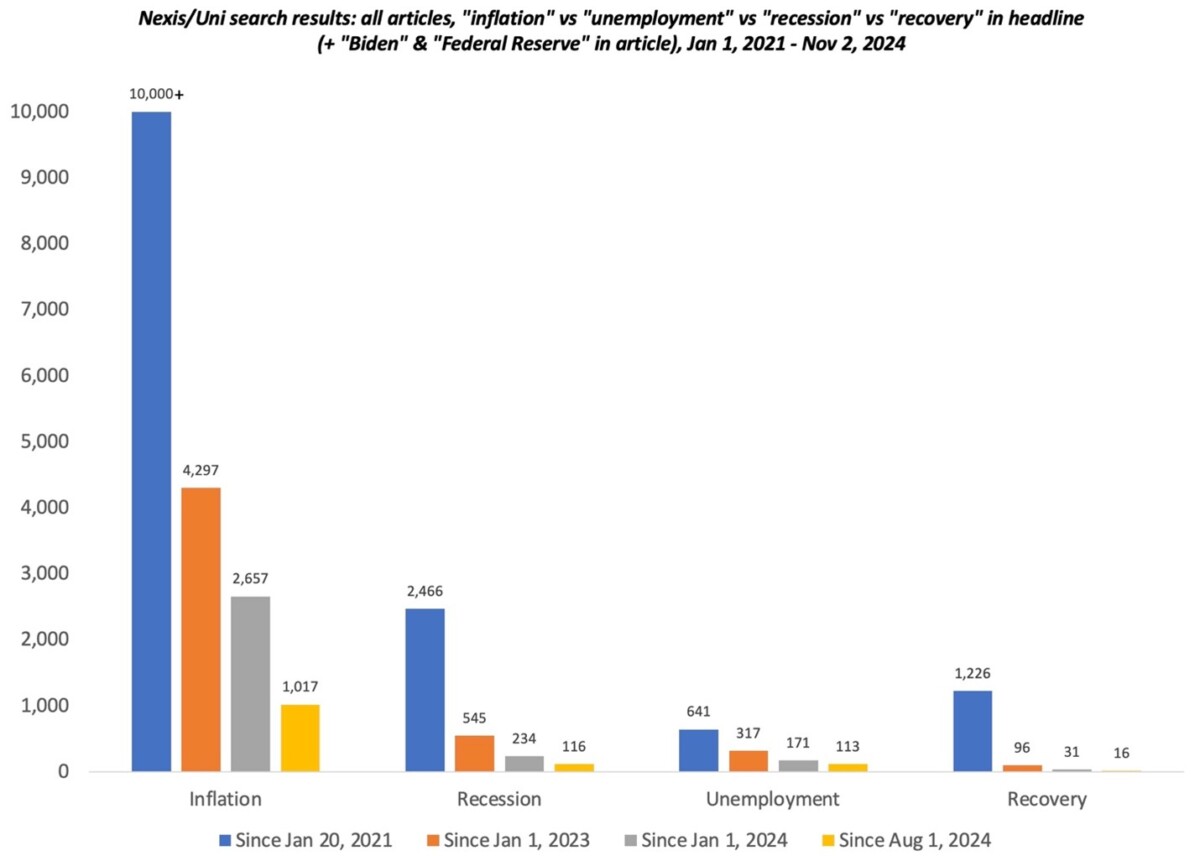

The backlash against incumbents is real, but it is only indirectly related to factual information about inflation and the economy. Instead, voter concerns appear to be driven more by perceptions about these things than material realities. This confirms findings of our past research, where we have found that the single greatest determinant of voters’ concerns with inflation in the US, in 2022, was not any measure of material well-being, but rather the amount of media – and especially conservative media like Fox News and talk radio – one consumes. We know that US media coverage since 2021 has been overwhelmingly biased toward negative topics (inflation and recession) instead of good news (low unemployment and the unprecedentedly rapid economic recovery), and this has been especially true of more conservative media outlets.

Put simply, to update James Carville’s famous chestnut, it appears to be the “information economy,” stupid. Americans have overwhelmingly heard that the US economy is terrible, and many voters – despite reporting that they are doing fine materially –clearly have internalized that message and taken it out on the incumbent political party.

Voters are clearly unhappy with incumbents. Perhaps, as Burns-Murdoch argues, voters are also reacting to broader “geopolitical turmoil” and immigration. What is far less clear is that voters punished the Democrats last week because they hate and are suffering from inflation and the terrible economy. The rush to make this the conventional wisdom about the 2024 US presidential election is premature.

This post written by Mark Copelovitch and Michael Wagner.

From pgl’s favorite right-wing blogger:

https://www.coffeeandcovid.com/p/unconditional-saturday-november-16

About 1/3 down, the section begins with The far-left Financial Times ran a soul-searching story yesterday headlined, “Trump broke the Democrats’ thermostat.”

After three graphics showing voter preferences, there is this:

The Financial Times observed the now-undeniable fact that, in every election between 1948 and 2012, voters always recognized the Democrat brand as “the party that stood up for the working class and the poor.”

But in 2016, the Times explained, “that flipped.”

Since Trump’s first term in 2016, voters began identifying Republicans with working-class issues. And now, in 2024, Democrats are now “seen primarily as the party of minority advocacy.” And, as the chart above suggests, even that narrow brand is crumbling.

The Democrats accuse Trump supporters of being deplorables and garbage and fascists and misogynists and racists, but they haven’t been listening to the people they are supposedly saving from Trump because all they can hear are the voices in their own echo chamber. Even liberal Bill Maher has gotten frustrated and fed up.

https://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2024/11/16/bill_maher_im_so_mad_at_the_democrats_and_their_aggressively_anti-common_sense_agenda.html

mark down the stock market unemployment rate and inflation today. Let’s measure them again in 2 and 4 years. If Trump is not beating all three measures, then he should be considered a failure, because according to maga we are in the worst economy ever. So none of his metrics should be worse than the worse economy ever, right? would you agree to these terms bruce?

It’s already started.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/11/18/democratic-national-committee-layoffs-union/

DNC layoffs with no severance leave staffers scrambling, union says

The cuts were announced starting on Wednesday night and were effective Friday; and DNC leaders did not tell staff how the layoffs were determined or whether additional cuts are planned, according to the union.

Mariana Alfaro

Updated November 18, 2024 at 6:34 p.m. EST

The Democratic National Committee workers’ union on Monday condemned layoffs by the organization, saying permanent employees were terminated last week with one day’s notice and no severance pay.

While staff jobs at campaign offices routinely end after elections, the DNC laid off permanent employees, including people who had been told their positions would continue after the election, the staff union said in a statement.

https://bsky.app/profile/dncstaffunion.bsky.social/post/3lb7onkze2c2j

So, some people were employed in temporary jobs, to deal with a particular event. Once the event took place, those jobs ended.

Some people had “at will” employment, as is entirely normal inthe U.S. labor market. Some of them were let go.

Scandalous.

1. Any article that contains, without snark, the phrase “The far-left Financial Times” can safely be disregarded as propaganda.

2. Did you even read the guest contribution?

3. “They haven’t been listening…” which is, of course, why the Democrats passed and defended Obamacare from Republican attempts to dismantle it, have repeatedly defended Social Security from the Republicans, expanded the EITC, passed the ARC (which included, among other things, a $36 billion bailout of union pension plans), and on and on… oh, what’s the use, I’m responding to Bruce Hall, after all.

Thank you. I didn’t have the energy.

Off topic – how not to write about energy markets under Trump:

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/11/06/oil-markets-future-still-uncertain-under-donald-trump-after-election-win.html

The article identifies three policies Trump has promised which would effect oil supply, demand and price:

Easing regulation on domestic production (increase supply?)

Increasing sanctions on Iran and Venezuela (decrease supply)

Tariffs (decrease demand)

The article initially takes for granted that reduced regulation would lead to an increase in supply, then undercuts that idea. Oil producing firms have expressed doubts about increased drilling – current prices don’t support opening new production. Not that Goldman is the last word in commodity forecasting, but the article cites a Goldman analysis suggesting lower prices are more likely than higher.

The article mentions Russian sanctions, then doesn’t follow up. What happens if Trump decides to give his Russian benefactors a gift? I don’t have a good idea of what lifting sanctions on Russia would do to supply, but it seems worth a look.

The article neglects alternative energy policy altogether. I don’t understand how a real energy-market watcher could do that. If Pigou is marched out of the building, what happens?

I’m happy to see some real research which backs up a common intuition about the news media. Faux news, Sinclair, Murdoch’s News Corp all exist to skew the news in favor of right-wing ideology. Those billions weren’t spent on a whim. There was strong reason to believe that people could be told what to think. That’s why the right is busy banning books and demanding control over classrooms.

Hippy-bashing was never just a fun hobby, and it is now on full display among Democrats. So-called moderates, looking for someone to blame, are going after progressives. That’s yet another symptom of how successful right-wing propaganda has been. Speaking up for workers, the poor and minorities is what lost Democrats the election? Not so, say Copelovitch and Wagner. Surrendering the news media landscape to the right is what did it.

Thanks for posting this important factual information!