It’s become commonplace to assert that the passage of the American Rescue Plan ignited inflation, dooming the prospects for the Biden and Harris candidacies. Consider this piece:

The least contentious point of criticism is the macroeconomic effect of the ARP, specifically on the issue that has wreaked havoc on the Biden administration, doomed progressive policies in this congress, and will likely hand control of Congress to the Republican party: inflation. The ARP is by no means the impetus for the inflationary pressures that plague the United States, but the role of $1.9 trillion in deficit spending in exacerbating an existing inflationary gap is undeniable. Passed as the American economy began to open up and regain full capacity, the ARP entered into an economy struggling with above-average demand due to pandemic saving patterns and below-average supply due to supply chain constraints, already a recipe for inflation.

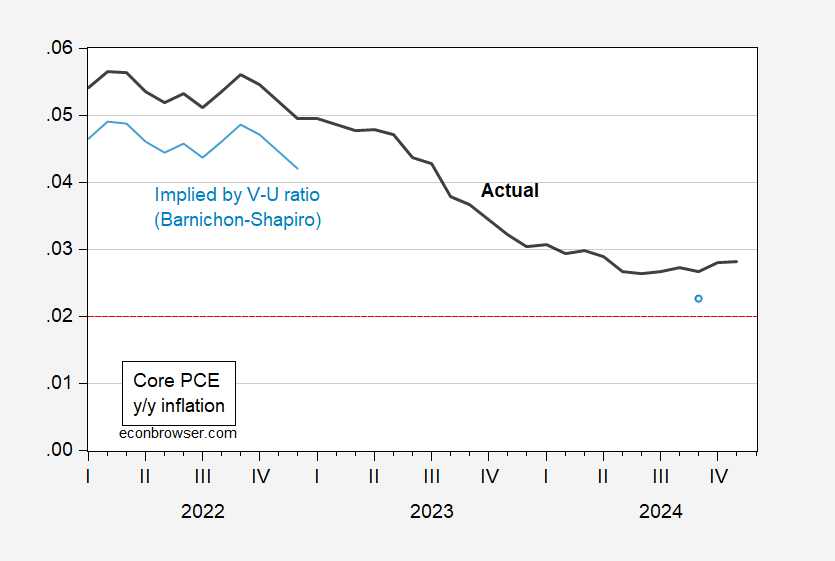

Sounds good, but I wonder exactly how much inflation was pushed up by excess aggregate demand, presumably coming from the ARP (but also the preceding CARES act, and other measures passed during the Trump Administration). I turned to this SF Fed Economic Letter entitled “How Much Has the Cooling Economy Reduced Inflation?” by Regis Barnichon and Adam Shapiro. Using their estimates of the modified Phillips curve (esp. the one relying on the vacancy-effective searchers, or V-S, ratio) of an approximately 0.75 ppts of 2022 inflation attributable to excess demand, and 0.4 ppts in September 2024 inflation.

Figure 1: Year-on-Year core PCE inflation (bold black), and implied inflation w/o excess demand (light blue). 2022 alternate inflation calculated subtracting 0.75 ppts from actual inflation. Horizontal dashed line at 2%. Source: BEA via FRED, Barnichon and Shapiro (2024), Figure 3, and author’s calculations.

The relevant question her is whether 0.75 ppts lower inflation in 2022, and a smaller deviation in 2023, would have tipped the balance. At the same time, the high aggregate demand which sustained strong wage growth and low unemployment (such that median household incomes were higher in 2024 than just before the pandemic) was due to the ARP and lagged effects from the previous fiscal packages. After all, a lot of the resilience of the economy throughout 2024 (remember how many people thought a recession in 2024 was a sure thing) is attributable to the consumer, and that in turn was due to savings built up from the Trump-Biden transfers.

See also Blanchard and Bernanke (BPEA, 2023).

I think the problem with the piece from Barnichon and Shapiro is that they define excess demand as being measured by one of these ratios. So it becomes a debate about definitions (“what is excess demand really”). I mean, I don’t know if you would say “excess demand” is the problem so much as we had a bigger demand shock than a supply shock.

The textbook macro story is that you have some upward sloping non-linear short-run aggregate supply curve (due to capacity constraints or what have you). A shift right in the aggregate demand curve in the non-linear portion causes prices to increase faster than growth. I think that’s pretty consistent with what we experienced. The difficulty is how do you measure that.

Just a reminder – Vacancies had deviated from hires prior to Covid’s arrival, raising questions about the reliability of this series. Here’s a picture of vacancies prior to 2020:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1CxGp

The deviation got lots worse after the Covid recession ended:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1CxHT

One explanation offered for the rise in vacancies was that the cost of listing jobs had fallen to the point that firms could afford to scoop up resumes when they didn’t have current openings.

It makes sense to use vacancies data – what else do we have for the purpose? – but we shouldn’t put a lot of faith in the results. If vacancies are exaggerated, then the influence of labor scarcity on labor costs and inflation might also be exaggerated.

I would also point out that this:

“…the role of $1.9 trillion in deficit spending in exacerbating an existing inflationary gap is undeniable.”

was written by an undergrad who is not even majoring in economics. The cock-sure tone, combined with the lack of substance, marks this kid as bound for law school. Useless.

Whopping huge, sustained deficits and monetary policy set for a depression, not recession. And then, of course, supply chain effects. Plenty of blame to the Fed (documented here at Econbrowser), excessive fiscal stimulus by both Trump and Biden administrations. Now, what to do about unsustainable structural deficits?