The Philadelphia Fed’s Coincident Index is out, 2.1% m/m annualized (2.6% y/y):

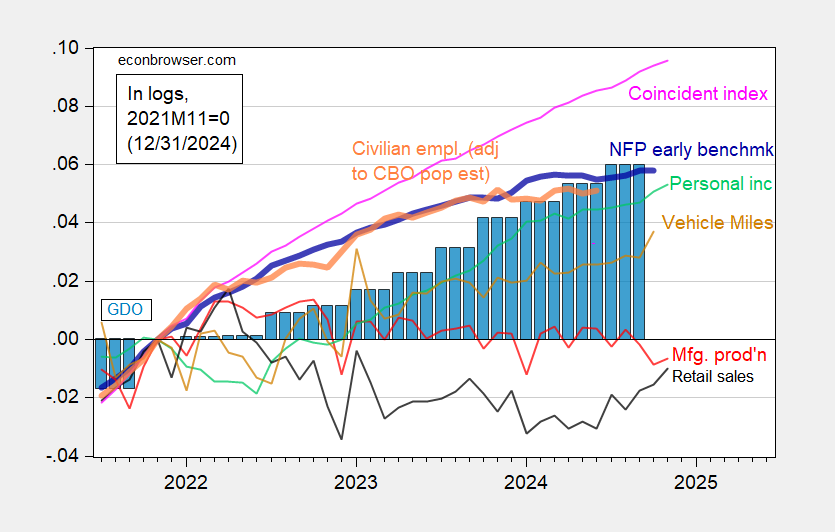

Figure 1: Implied nonfarm Payroll early benchmark (NFP) (bold blue), civilian employment adjusted using CBO immigration estimates (orange), manufacturing production (red), personal income excluding current transfers in Ch.2017$ (bold green), manufacturing and trade sales in Ch.2017$ (black), consumption in Ch.2017$ (light blue), and monthly GDP in Ch.2017$ (pink), GDO (blue bars), all log normalized to 2021M11=0. Source: Philadelphia Fed, Federal Reserve via FRED, BEA 2024Q3 third release, S&P Global Market Insights (nee Macroeconomic Advisers, IHS Markit) (12/2/2024 release), and author’s calculations.

Of the above, only personal income ex-transfers (light green) is a NBER BCDC key series (BCDC key series shown here).

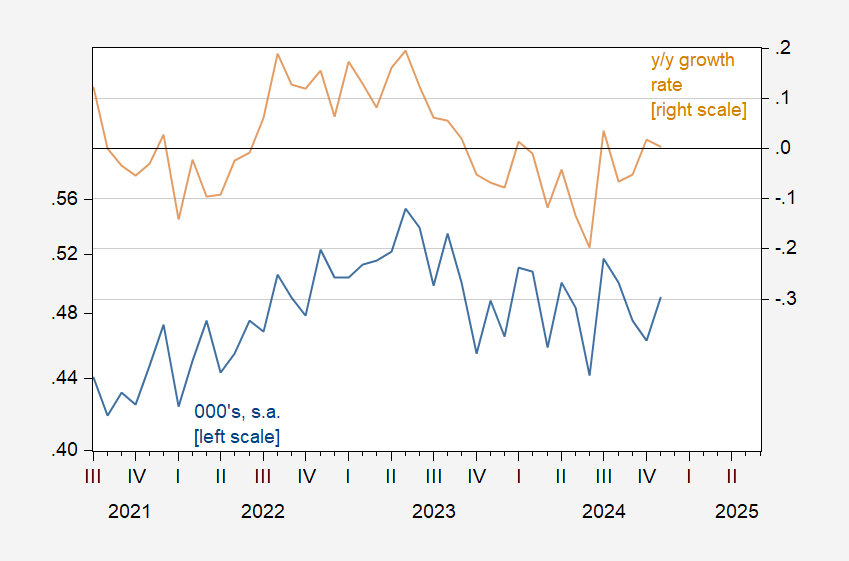

A favorite indicator of mine is heavy truck sales.

Figure 2: Heavy truck sales, 000’s (blue, left log scale), year-on-year growth rate (tan, right scale). Source: BEA via FRED, and author’s calculations.

It’s hard to see whether this indicates recession, even though we’re past a local peak. For context, here’s the evolution of these series before the last two recessions.

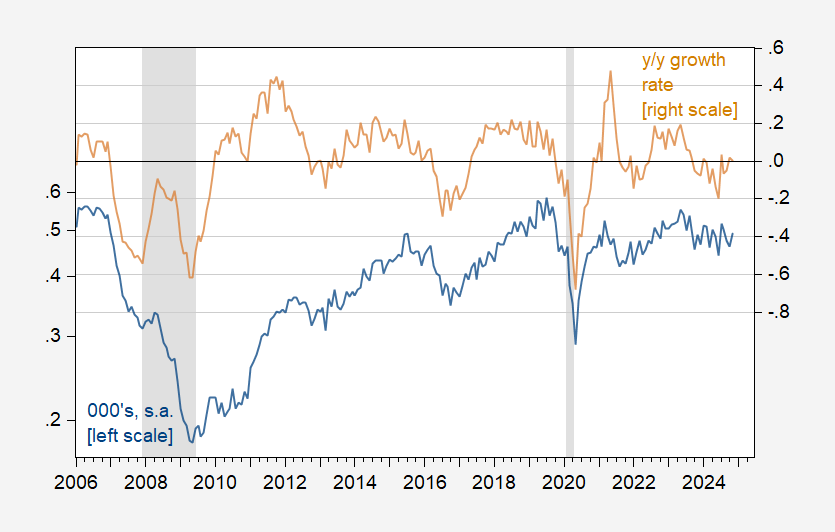

Figure 3: Heavy truck sales, 000’s (blue, left log scale), year-on-year growth rate (tan, right scale). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

On the basis of the y/y growth rate, you didn’t think we were headed to recession in 2019, then you shouldn’t think we are in 2024.

Off topic – New Year wool gathering:

With the coming of the New Year, the financial press is busy turning a look back at last year into prognotication for the new one. I want to play, too. So, Here’s a picture of recent events, as reflected in exchange rates:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1CyEZ

Mostly, the picture is of other currencies weakening against the US$. Within that general trend, there are particular details worthy of notice. Korea’s won and Brazil’s real were under particular pressure heading into the end of 2024. Brazl”s real, along with Mexico’s peso, spent the first half of 2023 strengthening against the US$ in anticipation of Fed rate cuts, but strong U.S. economic performance has undermined that effect.

Also evident is that Japan’s yen was weakened by the carry trade in 2023 and early 2024, then strengthened temporarily by unwinding of that trade in July and August of 2024. We may see further episodes of that unwinding, what with the BoJ planning more policy tightening.

The currency in this picture which is least volatile over the past 2 years is China’s yuan. As Setser, Pettis and their fellows have noted, China’s weak domestic demand has been pushing up exports while China’s latest merchantilist push has kept imports in check. The exchange rate isn’t needed as a trade tool, so is instead used to forestall hot money outflows.

Here’s the picture, but with Argentina and Turkey included:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1CyDO

Yikes! As you can see, adding these two special cases obscures what’s going on in other currencies. Two big regional economies suffering their own special problems and spilling those problems onto their neighbors through the exchange rate.

The Fed’s foot-dragging on rate cuts has induced a bit of volatility into exchange rates, and there are a number of indebted developing countries feeling the heat from high refinancing rates. On the other hand, the Fed’s gradual pace of cuts means that the whiplash normally suffered by the rest of the world when the Fed undertakes rapid rate adjustment has been avoided.

My big take-aways, for what they’re worth, are:

Turkey and Argentina are in a mess.

Brazil is showing increasing signs of stress.

Korea’s domestic political hijinks come with a cost. Even though South Korea is far from being in the soup with Turkey and Argentina, domestic disfunction clearly matters. That’s not a bad lesson for Europe and the U.S.

China, despite its many domestic troubles and the risks China poses for the global economy, is in some ways still a source of stability.

Persistent dollar strength is a sign that the rest of the world is not in great shape and is being propped up by U.S. strength. Fresh policy shocks – from the U.S. or from China – could do particular harm right now.