That’s my name for Trump’s 10% universal tariffs plan augmented with additional 60% on Chinese-made imports. h/t to Torsten Slok for the CBO letter. I show implied effects on PCE deflator inflation, and GDP relative to January 2025 CBO projection.

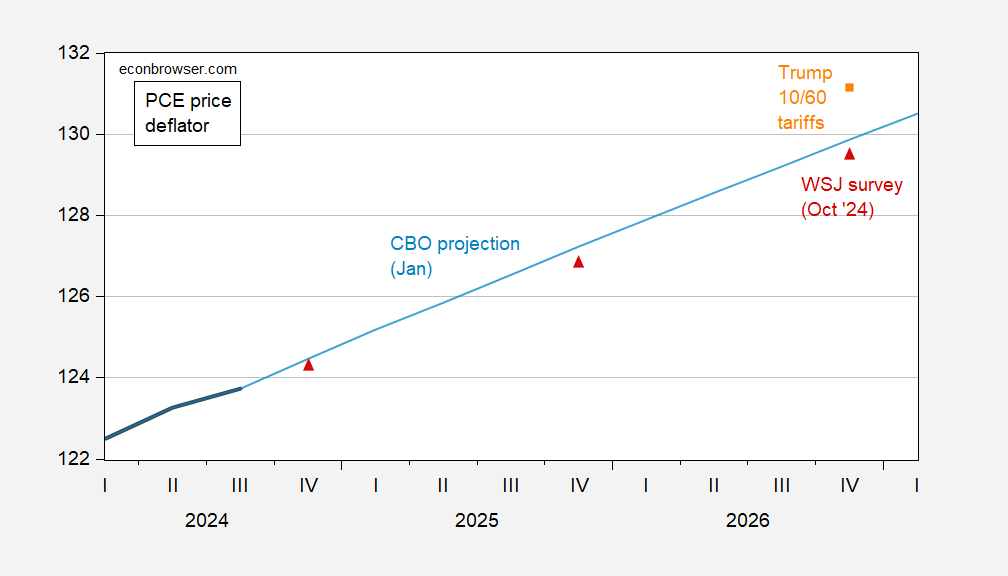

Figure 1: PCE deflator (bold black), CBO January projection (light blue line), CBO implied PCE deflator under Trump 10/60 plan (orange square), WSJ mean November survey forecast (red triangle). Source: BEA via FRED, CBO Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO letter, WSJ, and author’s calculations.

Interestingly, the January 2025 WSJ survey mean indicates a PCE level about the same as the CBO implied level — although this combines the tariff, deportation, and trade policy effects.

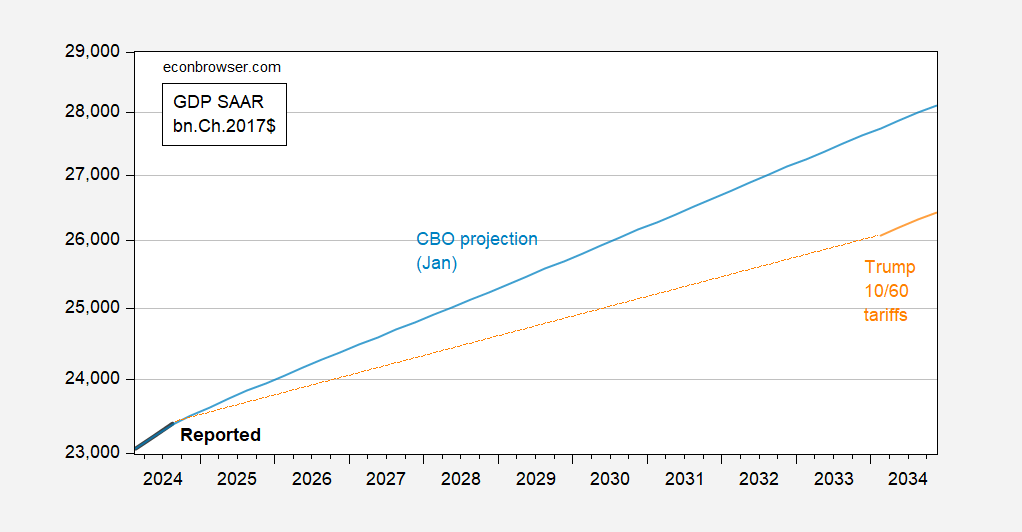

What about GDP? I show the CBO projection, and the implied deviation.

Figure 2: GDP (bold black), CBO January projection (light blue line), CBO implied PCE deflator under Trump 10/60 plan (orange). Source: BEA via FRED, CBO Budget and Economic Outlook, CBO letter, and author’s calculations.

While CBO mentions in its letter the impact of uncertainty, it does not apparently incorporate them into the estimated effects.

The United States has implemented no increases in tariffs of this size in more than 50 years, so there is little relevant empirical evidence on their effects. As a result, CBO’s estimates of the economic effects of large changes in tariffs are very uncertain. Nevertheless, the direction of the estimated effects is consistent with previous experience. The actual effects would depend on how businesses and consumers in the United States and other countries responded to the higher tariffs and the extent to which foreign governments responded with higher tariffs on U.S. exports. The estimates reported above reflect the expectation that U.S. trading partners

would respond to the increases in tariffs with retaliatory increases of a similar magnitude.

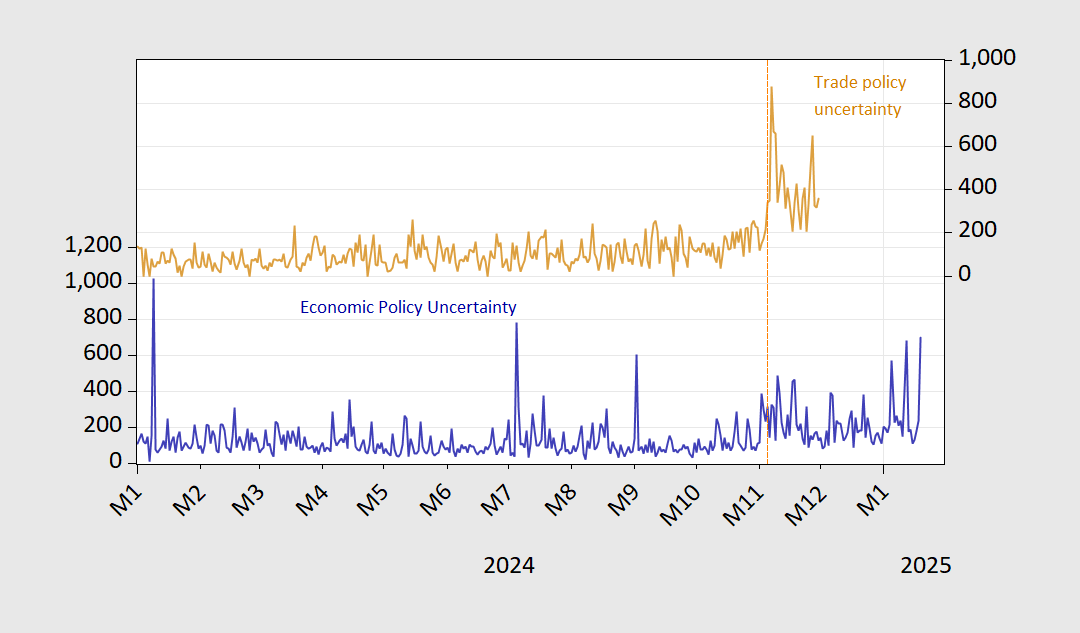

Under Trump 1.0, EPU and trade policy uncertainty rose when the Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs were announced. Now, uncertainty is elevated even before the inauguration.

Figure 3: EPU (blue, left scale), Trde Policy Uncertainty (brown, right scale). Source: https://policyuncertainty.com, https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/tpu.htm.

In one sense, tariffs amount to an increase in national saving through increased taxation (assuming no other change in tax policy). When CBO observes that the ultimate effect depends on the response of all and sundry to tariffs, that response can also be thought of as changes in saving. Foreign tariffs on U.S. goods (and services?) would also increase taxation.

In the near term, households would reduce saving – that’s what they do – but over time would reduce spending to offset the income effect of higher prices (taxes). Same for businesses.

We will probably see an exaggerated impact from tariffs immediately after they are imposed because firms and households have been front-running tariffs. After that, progressive adjustment to lower real incomes will begin.

Whether increased government saving (assuming no other change in tax policy) would result in an increase in national saving in the long run is an open question. The private sector might fully offset any increase in government saving, whether for Ricardian reasons or just due to income effects. The Paradox of Thrift might bite us in the backside, actually lowering the saving rate. An active Keynesian response by governments might lower the saving rate further.