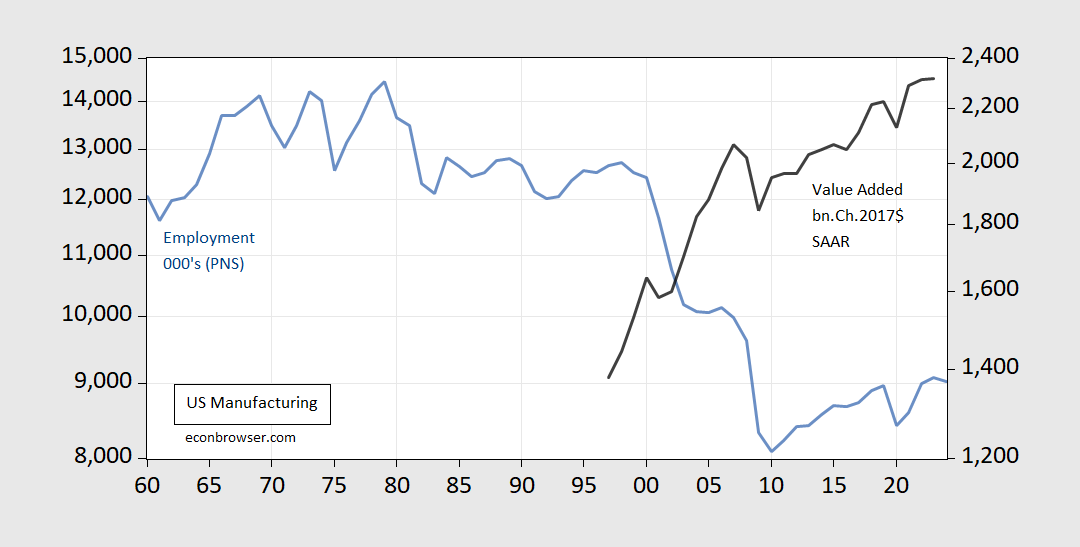

A reader sends me a missive with this line, and (among others) a picture of manufacturing employment. I reproduce (on an annual basis) this series back to 1960 in the figure below.

Employment in manufacturing did take a plunge in 2001. I didn’t know it was going to take quite the plunge it did, but I did see employment declining (then serving on CEA).

Figure 1: Manufacturing employment, production & nonsupervisory, 000’s (blue, left log scale), and manufacturing value added in bn.Ch.2017$ (black, right log scale). Source: BLS, BEA.

Value added rises. Why? Specialization in high value added parts of value chains (cf international textbooks) as predicted by comparative advantage in tasks.

Mechanically, how can these trends in employment and value added do what they do? Well, it’s due to something called “productivity”. The same reason why employment in agricultural production (not processing, but farming etc.) is down yet value added output is up.

Just sayin’.

The reader also comments:

Just coincidentally and not at all related to any of this, China’s economy and rise as a military power soared about the turn of the century… or so we are supposed to believe.

The drop in manufacturing employment is not, in my view, unrelated to the entry of China into the world trading system. Comparative advantage would suggest reallocation should occur (gains from trade occur because of changes in consumption and production, after all). And there’s no doubt China has developed as a economic power and strategic competitor. On the second point, I wouldn’t be writing all those posts on PRC activities around Taiwan.

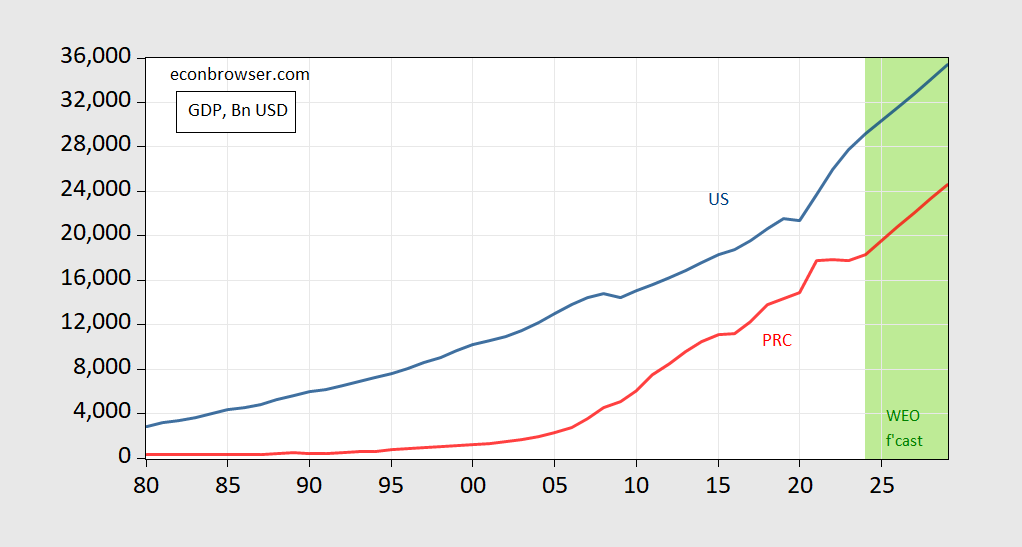

But good to keep things in mind. First, the US remains the world’s largest economy evaluated at market exchange rates.

Figure 2: US GDP (blue), China (red), in bn. US$. Source: IMF WEO (October).

There is no longer a projected crossover, as had been projected in earlier years.

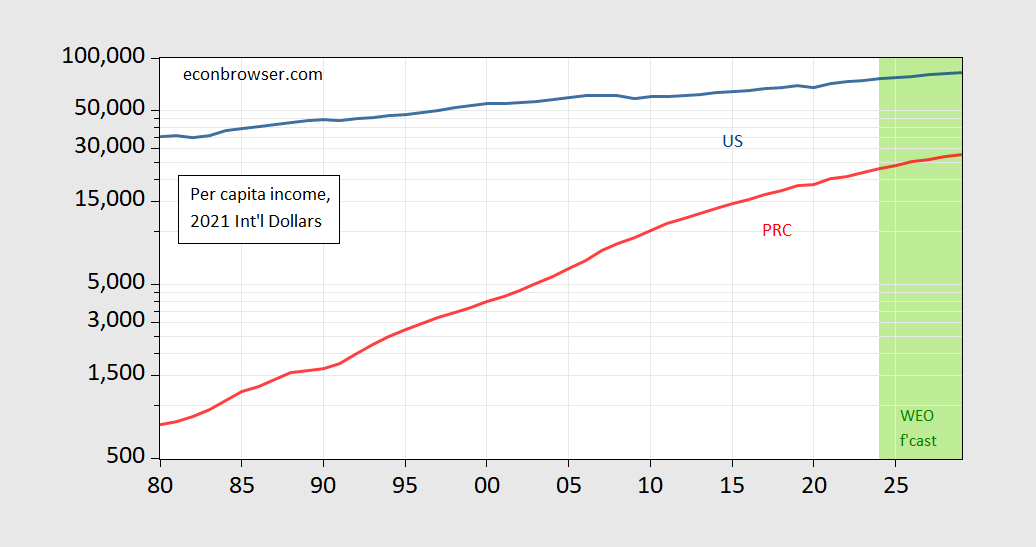

While PPP dollars would be more useful for comparing standards of living, market rates are more for considering economic power in the world economy, and ability to project influence. What about per capita in PPP International $?

Figure 3: US GDP per capita (blue), China per capita (red), in bn. PPP 2021 International$ . Source: IMF WEO (October).

Hard to see rapid convergence in PPP per capita.

This doesn’t mean China does not have real global economic impact. I’d just say we want to keep things in perspective.

An interesting change has begun to take shape although the impact on employment and the economy hasn’t been apparent yet.

https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2024/03/has-us-china-decoupling-energized-american-manufacturing/

>i>In recent decades, the US has grown increasingly dependent on imports from China to access a vast variety of goods. The FRED graph above shows Chinese import data: From 1990 through 2016, as China became a globally integrated economy, the US import share from China grew steadily, from close to 2% of aggregate US imports in the late 1980s to close to 22% in 2016.

In recent years, however, policies have been enacted to reduce this dependence on China, as illustrated by the trade war during the Trump administration and the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. Indeed, the US import share from China has declined from 22% to 14% since 2016.

As the cost of importing Chinese goods has increased, the incentive to produce goods domestically has also increased. So, to what extent is the US-China decoupling leading to a resurgence of American manufacturing? We investigate this question in the FRED graph below, plotting manufacturing investment in structure and equipment, as well as employment and output.

On the one hand, there has been a resurgence of manufacturing investment in structures since 2020. These investments may indicate that American manufacturing overall is indeed resurging, with investments in structures more than doubling in a short period.

On the other hand, output, employment, and investments in equipment haven’t increased in tandem with the growth of investment in structures. We interpret these findings as evidence that American manufacturing may be resurging, but that the resurgence may take time: Investment in structures is time-intensive and precedes the growth of employment and output that results once new manufacturing plants are completed.

China does have a comparative advantage in labor, which explains some of our mutual pattern of trade. Correct me here, but as I understand it, comparative advantage explains the mix of goods traded, but not the balance.

A number of people smarter than I am have noted that the U.S. may actually have a comparative advantage in IOUs, but even so, piling up U.S. IOUs is a policy choice, not the natural consequence of private exchange.

Off topic – Conditions in California:

https://calmatters.org/environment/wildfires/2025/01/dry-danger-zone-california-fires-climate-change/

We were recently treated to assertions that California’s extraordinary fires are the result if land-management and water-use decisions in California, and decidedly not because of climate change and a long drought. Those assertions were utterly wrong, and clearly the product of right-wing spin efforts. As thr Cal Matters article describes, soil moisture is only around 5% of normal in parts of Southern California.

Here is another article from the same source, noting that the return to “normal” rainfall in California is far from normal:

https://calmatters.org/environment/water/2025/01/california-rain-drought-north-south/

The north of the state has enjoyed above-average rainfall, the south eight months far less than average rainfall. If all that mattered was the amount of water flowing into reservoirs, then this pattern of wet and dry wouldn’t matter. Of course, ground water matters, too – a lot. Soil moisture keeps plants alive where irrigation doesn’t. Soil moisture discourages fire. Evaporation lowers ground temperature.

So the slew of words all about how insufficient water wasn’t a factor (and let’s ignore the wind, too) wasn’t wrong just in the details. It was utterly, comprehensively wrong, wrong in the basic facts and the details, the kind of wrong that only comes from intent, from disregard for the truth.

Re: Reservoir Levels

The yellow is the head space to accept the spring melt.

https://cdec.water.ca.gov/resapp/RescondMain

The smelt has plenty of water to swim in.

Remember the California water equation: NorCal stores it. Central Valleys use it. SoCal pays for it.

Trump has said he won’t approve assistance for California wildfires if Newsom won’t send more water south to farmers in the SJ Valley. Interesting because NE California —where lots of water is stored—is represented in the House by Republicans LaMalFa, McClintock, and Kiley whose districts have delivered heavy majorities for Trump. Many Devastating fires have occurred in these areas where Trump has captured 60% + of the vote.

The Dixie Fire (almost a million acres) is a prime example. The fire scorched four counties (Plumas, Lassen, Tehama, Shasta ). Both Tehama and Shasta were 70% for Trump. Paradise residents (Camp Fire) were +10 Trump in 2016.

There are, too, numerous large reservoirs located in the NE in addition to the biggest, Shasta and Oroville. (Last I saw, both were near 80% capacity) Hard to imagine —or maybe not—that avid Trumpers in these counties won’t get help unless more water is delivered to carrot growers 400 miles south in Kern County.

Makes little sense, but what else is new?

Jobs in manufacturing were a big deal decades ago because they were unionized and paid a substantial premium over non-manufacturing jobs. These highly paid manufacturing jobs were the path to the middle class for millions of workers. This is no longer true. Few manufacturing jobs are unionized and non-manufacturing jobs now pay a premium over manufacturing jobs. In 1980 over 30% of manufacturing jobs were unionized, enough to pull up wages in non-union manufacturing as well. Today it’s less than 10%. Labor laws and enforcement have been gutted and manufacturing jobs have migrated south to “right-to-work” (which should be called right-to-work-cheap) states.

So there’s no longer any reason to obsess over manufacturing jobs. The emphasis should be on unionization, which is occurring faster in the service sector.

Vivek Ramaswamy has been run out of DOGE.

The Department of Government Efficiency is working. They’ve already cut wasteful management in half. If they can get rid of the other half we will be really getting somewhere.

Off topic – Auto emissions and climate change:

https://theicct.org/publication/vision-2050-global-zev-transition-2024-jan25/

Good news, of a sort. Th latest projections from the International Council on Clean Transportation includes a scenario in which peak emissions occur this year. That’s only one scenario, and relies on policy changes, as written, but not in stone.

This is an improvement over earlier projections, which is the good news. The fact that it leaves us coming down from a Greenland-melting, Los Angeles-burning, extinction-inducing level of emissions takes some of the happy feeling out of the news.

For those who are suspicious of greenwashing – and you have good reason – ICCT is the group that ratted out VW for lying about emissions. They’re solid.

Speaking of China, and of stark changes in performance, the (my) suspicion is that China is in a balance sheet recession. A balance sheet recession results when a decline in asset values induces a decline in borrowing in an effort to balance assets with liabilities. Japan and the U.S. have both been through balance sheet recessions, and the U.S. dragged a good bit of the developed world along during the late aughties.

China has suffered a collapse in housing values, in the value of construction companies and land and in the value of related debt. China’s stock market is also losing value. That sounds like what happened in Japan and the U.S. (and Ireland and Portugal and…).

I have not found any data on real household net worth in China, but JPM was nice enough to gather up some helpful information on household borrowing:

https://am.jpmorgan.com/au/en/asset-management/adv/insights/market-insights/market-updates/on-the-minds-of-investors/a-dive-into-chinese-households-balance-sheets/

Scroll down to “The Liability Side” and you’ll see that households’ outstanding mortgage debt is falling, as are credit card balances. Bank loans are still increasing, but at a declining rate. Mortgages account for 65% of household debt, credit cards for about 15%. That leaves about 20% of the Total, at most, for bank loans.

Trading economics has data on total bank lending, which also turns out to show a decline, consistent with a balance-sheet recession:

https://tradingeconomics.com/china/banks-balance-sheet

“Lowest since 2012” is probably not good:

“Chinese banks extended CNY 990 billion in new yuan loans in December 2024, above CNY 580 billion in November which was the lowest since 2012…”

China is, of course, different than other countries. Whether the “command” part of “command economy” is enough to prevent a harsh recession, I can’t say. Reasonably, the issue ought not to be “recession or no recession”. Definitions of recession vary, as do depth and duration of recession. Divergence from trend is a more quantifiable and consequential measure of the damage suffered due to the collapse of asset values. So here’s the picture:

https://tradingeconomics.com/china/gdp

Hit the “Stats” and “10Y” buttons and the impression you (I) get is that Chinese output is as far below trend now as during the worst days of the Covid plague. Crude stuff, I know, but it’s the only way I’ve found to link to a picture which addresses the divergence issue.

Bloomberg has an article on loss of manufacturing jobs and the “left-behind counties” in the U.S. Trump did nothing for them in first term and Biden tried but they didn’t come back as much as higher GDP (primarily Dem) counties. Here is the underlying report https://eig.org/left-behind-places/

Because I work with individuals with disabilities in Wisconsin – I see a bigger problem – many of these “left behind” counties are rural/small towns with declining and aging populations – I foresee a declining tax base and increased health care costs and a lack of front-line care givers (more immigrants – please move to Wisconsin) –

https://doa.wi.gov/Pages/LocalGovtsGrants/Population_Projections.aspx (also just read “United States Dementia Cases Estimated to Double by 2060” https://nyulangone.org/news/united-states-dementia-cases-estimated-double-2060 – so even if we increase the retirement age – it will not help much)

I don’t see Trump’s deportation of needed workers and unfunded tax cuts to fuel speculation in Crypto Currency – helping these counties.

James, you claim that illegal immigrant workers are needed to fill jobs, yet in 2024 they cost the city of New York alone billions of dollars for food, shelter, and medical care. What is needed is not more illegal, chaotic immigration with high social costs, but more legal, managed immigration/temporary workers and a process that supports that through business sponsorships that can be justified by unfilled jobs.

This is a few years old (and certain commenters may take umbrage at that):

People working part-time who would prefer to be working full-time comprise a large group in the United States. These people may be referred to as working “part time for economic reasons,” “involuntarily part-time,” or “underemployed.”1 Since 1994, there has been an average of 5.4 million underemployed workers in the United States, rising to more than 9 million during the 2008–2009 Great Recession and to more than 10 million in the 2020 recession caused by the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Also: https://www.businessinsider.com/most-graduates-us-college-cant-find-job-underemployed-decade-2024-2?op=1

Perhaps those nice higher paying manufacturing jobs would be nice.