It seems like a funny question to ask given Russian government debt to GDP isn’t that large. Craig Kennedy argues that taking into account forced bank lending means that (contingent) government liabilities are much larger than conventionally-defined public liabilities (report here). The summary:

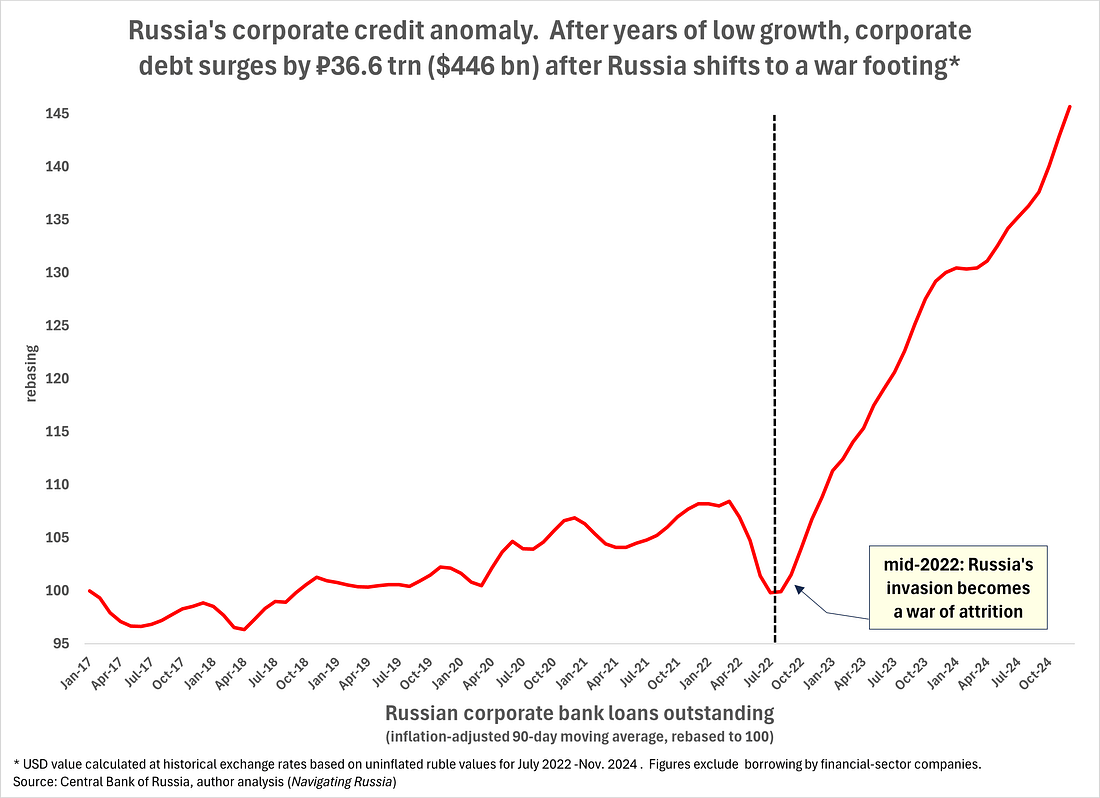

Moscow has been stealthily pursuing a dual-track strategy to fund its mounting war costs. One track consists of Russia’s highly scrutinized defense budget, which analysts have routinely deemed “surprisingly resilient.” The second track—largely overlooked until now—consists of a low-profile, off-budget financing scheme that appears to make up a major portion of Russia’s overall war expenditures. Under legislation enacted in February 2022, the state has taken control of war-related lending at Russia’s major banks. It is directing them to extend preferential loans—on terms set by the state—to a wide range of businesses providing goods and services for the war. Since mid-2022, this state-directed war-funding scheme has helped drive a large part of Russia’s anomalous ₽36.6 trn ($446 bln) surge in overall corporate borrowing.

Initially, this off-budget war-funding scheme proved advantageous to Moscow by helping limit defense spending in the budget to levels that are easily managed. That misled budget-watchers into concluding—incorrectly as it turns out—that Moscow faces no serious risks to its ability to sustain funding for its war on Ukraine. More recently, however, Moscow’s heavy reliance on state-directed preferential lending has begun to cause serious, adverse consequences at home. It has become the main driver of Russia’s 10% inflation and has sent the Central Bank’s key rate to a record 21%.

More broadly, Russia’s off-budget war debt is significantly elevating systemic credit risk, both for the near- and medium-term. High interest rates are driving up corporate distress levels in the “real” economy and raising fears of widespread bankruptcies. The Central Bank has voiced concern over “aggressive” lending and inadequate capital buffers in the banking industry. What’s more, the state has now saddled the banks with large amounts of problematic, corporate war loans. Many could turn toxic once the shooting stops and defense contracts get cancelled. Worse still, relaxed oversight rules on defense-related loans mean bank regulators might not see these problems arising until it’s too late.

By late 2024, the Kremlin had been briefed on these rising risks and warned that change is needed. This poses a dilemma for Putin: continue relying on off-budget debt, and you further increase the risk of cascading credit events that undermine Russia’s image of “surprising resilience” and weaken its negotiating leverage. The alternatives: a major increase in the budget deficit—with the bad optics that entails—or a sharp reduction in spending on the war. This may explain Putin’s recent complaint to his generals that they can’t “keep pumping up spending to infinity.”

These new developments are likely to affect Moscow’s war calculus in two ways:

- Moscow will be less inclined to believe time is on its side—the longer it must fund elevated war costs, the greater the risk of escalating credit events;

- Moscow will prioritize sanctions relief aimed at boosting cashflows to help with politically perilous post-war debt restructuring and rearmament. Concessions that would provide the greatest cashflow relief include (i) an easing of oil sanctions, (ii) the resumption of pipeline gas deliveries to Europe and (iii) the unfreezing of Russia’s wealth fund.

Given Russia’s financial challenges, maintaining these constraints on Russia’s cashflows insures Ukraine and its allies retain substantial leverage. If kept in place past a ceasefire, they could be instrumental in securing a final, comprehensive peace settlement—including reparations.

Kennedy presents this picture of corporate borrowing to buttress his argument. See the entire report here.

Source: Kennedy (2025).

Contrasting view, see Kolyandr and Prokopenko (2025) (Carnegie Endowment).

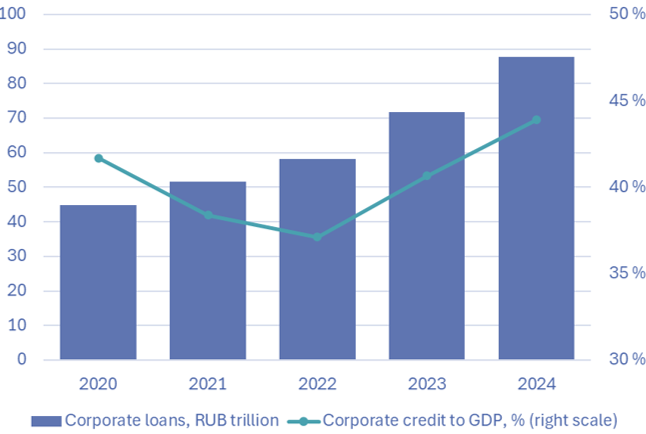

BOFIT provides this graph of corporate loans (in RUB, as share of GDP):

Two things –

First, forcing banks to lend to military firms undercuts the effect of tight monetary policy. That helps explain why high rates haven’t slowed the economy more than they have. However, the non-military side of the economy is doubly disadvantaged, because when a large part of the economy is shielded from the effects of high rates, rates need to be even higher to deal with inflation. The entire transmission of contractionary monetary policy ends up going through the civilian economy. We kinda knew that was the case in general, but this shows how it’s accomplished.

Second, there may be a big new sanction brewing in Europe:

https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-lashes-out-against-eu-plans-to-seize-its-shadow-fleet-in-the-baltic-sea/

European leaders are considering shutting down Russia’s shadow oil fleet. Russia’s reaction suggests the threat is serious. Kennedy suggests Russia’s economy is on a short clock if sanctions are maintained. Imagine what happens if the shadow fleet is shut down.

How high debt/GDP can get before it becomes a problem?

At first sight it looks like Russia still has years before it becomes unmanageable.

Sceptic but Optimistic: Well Ireland looked like it was a paragon of fiscal rectitude…until contingent liabilities became government liabilities when the banking sector had to be bailed out.

Russian industry is actively complaining that they cannot sustain current rates of borrowing. Also, rate is higher for government borrowing too. So, in terms of fiscal stability even if there is no need to bailout industry this debt is harder to pay back than western debt with low rates. And if industry starts defaulting Russia would have to bail out – they need military production.

On the other hand, even if Russia fully nationalizes it may manage to go on for some time. Just as Soviet Union did. So, it is really a question of how much pain are they willing to take

Eggs:

https://en.haberler.com/the-united-states-will-import-15-000-tons-of-eggs-18373612/

Turkey is sending 15,000 tons of eggs to the U.S.

Typically, the U.S. is the second largest egg exporter, behind the Netherlands. Now, we are dealing with the bird flu epidemic by importing eggs. Just remember, trade is bad.

Off topic – U.S. policy toward Taiwan:

The State Department fact sheet entitled “U.S. Relations with Taiwan” has undergone a small but significant change in wording.

https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-taiwan/

The second paragraph of this document now begins:

“The United States’ approach to Taiwan has remained consistent across decades and administrations. The United States has a longstanding one China policy, which is guided by the Taiwan Relations Act, the three Joint Communiques, and the Six Assurances. We continue to have an abiding interest in peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait. We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side.”

Until the 13th of this month, the wording had been:

“We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side; we do not support Taiwanese independence…”

The bit about opposing Taiwanese independence has been dropped.

Recall that during the first term of the felon-in-chief (herinafter “FIC”), there was a substantial elevation of official contacts between the the U.S. and Taiwan and regularized arms shipments to Taiwan. China threw tantrums in response. The Biden administration maintained increased contacts and arms deliveries.

Christopher Miller’s “Project 2025” chapter on the DOD had this to say about Taiwan and China:

“Prioritize a denial defense against China. U.S. defense planning should focus on China and, in particular, the effective denial defense of Taiwan.

“This focus and priority for U.S. defense activities will deny China the first island chain.”

1. Require that all U.S. defense efforts, from force planning to employment and posture, focus on ensuring the ability of American forces to prevail in the pacing scenario and deny China a fait accompli against Taiwan.

2. Prioritize the U.S. conventional force planning construct to defeat a Chinese invasion of Taiwan before allocating resources to other missions, such as simultaneously fighting another conflict.

*********

You may have noticed that China is once again throwing a tantrum, flying military aircraft into Taiwanese airspace, making a grab for South Korean territorial waters and the like.

There had been speculation that the FIC’s drooling over Greenland and Canada indicated a “spheres of influence” policy – bad for Taiwan and our Asia-Pacific allies. Nothing in Christopher Miller’s “2025” contribution supports that view, nor does the change in the text of the Taiwan fact sheet.

In a cursory search, I’ve turned up nothing from China in response to the change in wording. I expect we’ll get one soon.

And today on TV we have infamous economist (and definitely non-epidemiologist) Kevin Hassett opining on how to handle bird flu. It wasn’t enough that he was responsible for thousands of deaths from Covid due to his covering for and irresponsible submission to Trump. He’s back for more on the virus beat.

He has discovered the incredible fact that chickens don’t fly but ducks and geese do, so you just need to provide a security perimeter for millions of chickens to keep out ducks and geese (neglecting the fact that bird flu also infects cows, foxes, skunks, opossums, cats, dogs and humans). Meanwhile he says they have “top men” working on it at a time when Elon Musk is firing thousands from the USDA and CDC, and bird flu reports have been wiped from the CDC web site.

It seems that Hassett, like Musk and his minions, is infected with a severe case of the Dunning-Kruger disease.

Hasset also lied about economics in so many ways. Like his claim that 10-year government bond yields have declined by 40 basis points since Trump’s election.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10/

government bond yields rose by about 40 basis points and then retreated a bit.

Seems JohnH is writing copy for Hassett these days. I wonder what he would say about this post!