Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell, Professor of Economics at the University of Houston, Sebin Nidhiri and Swati Singh, Ph.D. students at the University of Houston.

The Federal Reserve Board started a strategy review at the beginning of 2025 which it intends to complete by late summer. After its only previous review, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) adopted a far-reaching Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in August 2020. The framework contains two major changes from the original 2012 statement. First, policy decisions will attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. Second, the FOMC will implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

The 2019 review was heavily influenced by economic performance over the previous decade, including the Effective Lower Bound (ELB) period from December 2008 – December 2015 and the difficulty in raising inflation to the Fed’s 2 percent target. While it was reasonable to assume in 2019 that the issues over the previous decade would continue, the 2025 review will be more difficult because, hopefully, the next five years will not involve a repetition of the Covid-19 recession, recovery, inflation, and disinflation. Powell (2025) has recently made it clear that the FOMC is reconsidering the language about both shortfalls and FAIT.

This post is based on our paper, Policy Rule Evaluation for the Fed’s Strategy Review,

where we analyze policy rules that are either in accord with the original statement or inspired by the revised statement and use the rules to evaluate monetary policy using the Linearized Version (LINVER) of the Federal Reserve Board/United States (FRB/US) model.

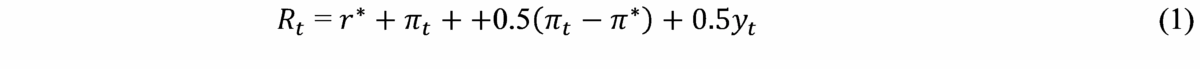

The Taylor (1993) rule is as follows,

where Rt is the level of the short-term federal funds interest rate prescribed by the rule, πt is the annual inflation rate, π* is the 2 percent target level of inflation, yt is the output gap, the percentage deviation of GDP from potential GDP, and r* is the neutral real interest rate that is consistent with inflation equal to the target level of inflation and GDP is equal to potential GDP in the longer run. When inflation equals its 2 percent target and GDP equals potential GDP, the federal funds rate equals the neutral real interest rate plus the 2 percent inflation target.

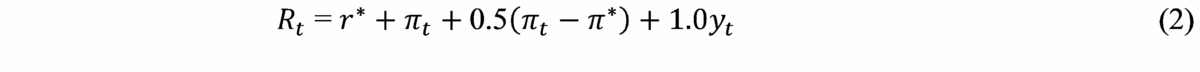

Taylor (1999) and Yellen (2012) analyzed an alternative to the Taylor rule that is called the balanced approach rule, where the coefficient on the inflation gap is 0.5 but the coefficient on the output gap is raised to 1.0. The balanced approach rule is

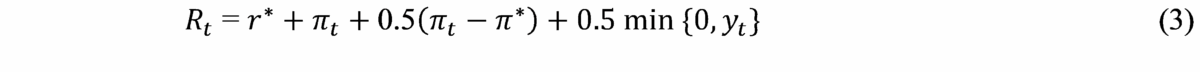

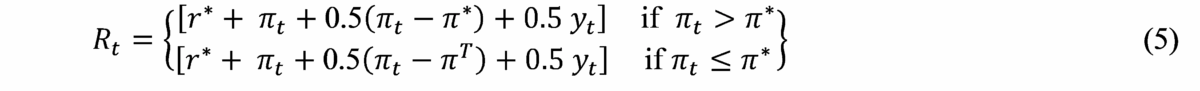

The Taylor (shortfalls) rule mitigates employment shortfalls instead of deviations by having the FFR only respond to unemployment if it exceeds longer-run unemployment. The version with the output gap is,

If the output gap is negative, the FFR prescriptions are the same as with the Taylor rule. If the output gap is positive, the FOMC will not raise the FFR solely because of low unemployment. The balanced approach (shortfalls) rule is the same as the Taylor (shortfalls) rule except that the coefficient on the output gap equals 1.0 instead of 0.5. Shortfalls rules were discussed in the March 2025 FOMC meeting.

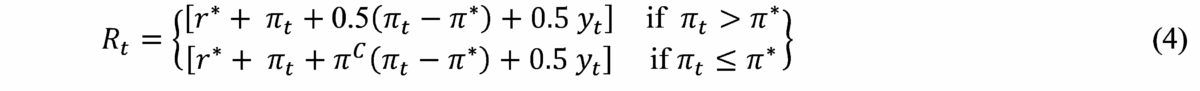

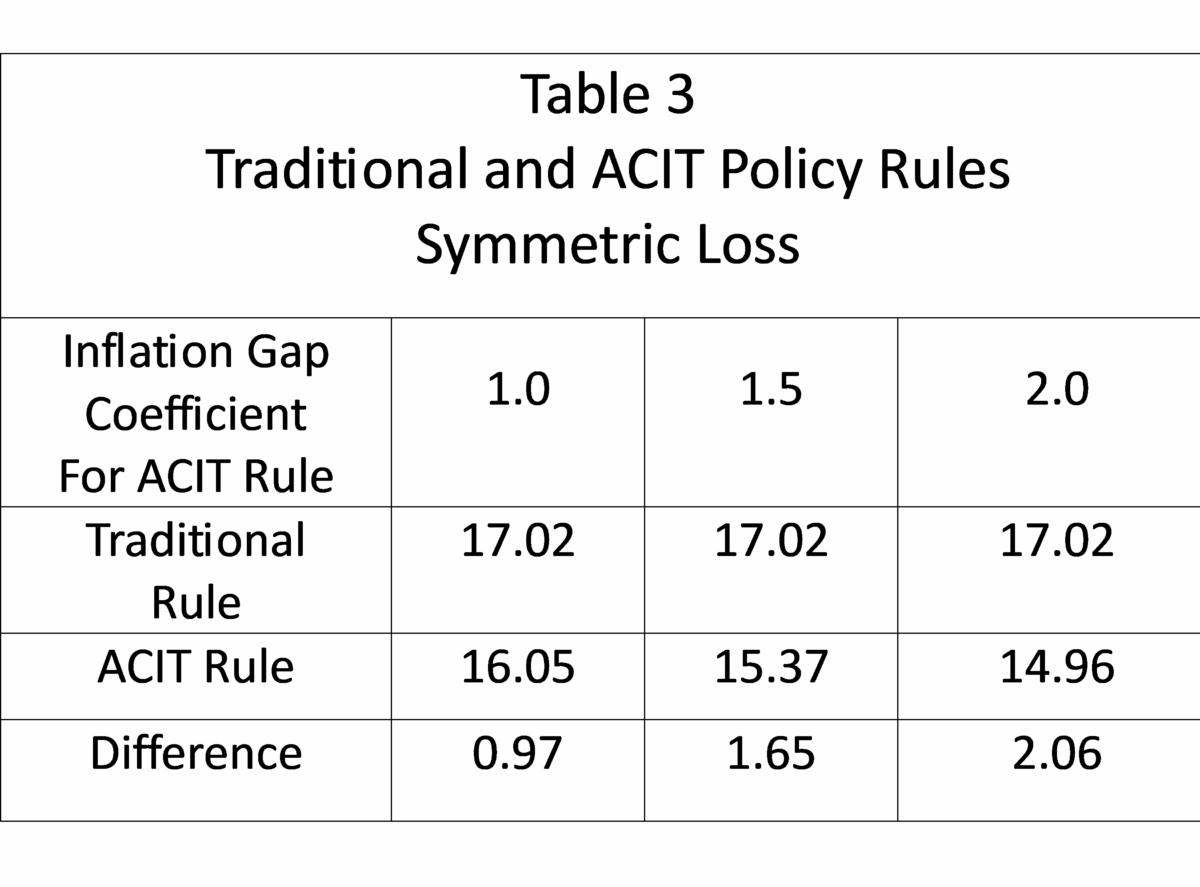

We propose two new types of rules inspired by the revised statement. The first is the Asymmetric Coefficient Inflation Targeting (ACIT) rule where the coefficient on the inflation gap is larger when inflation is below 2 percent. The ACIT Taylor rule is

We analyze rules where the coefficient πC on the inflation gap (πt-π*) when πt < π* is 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. When inflation πt exceeds the 2 percent inflation target, the rule is identical to the Taylor rule. When inflation πt is less than the 2 percent inflation target, the rule provides more stimulus than the Taylor rule. The balanced approach rule version is identical to the Taylor rule version except that the coefficient on the output gap is 1.0 instead of 0.5. The ACIT rule provides more stimulus than the traditional rules when inflation is below 2 percent and the same amount of restraint when inflation is above 2 percent. Once inflation exceeds 2 percent, policy acts to reduce inflation to, but not below, the 2 percent target.

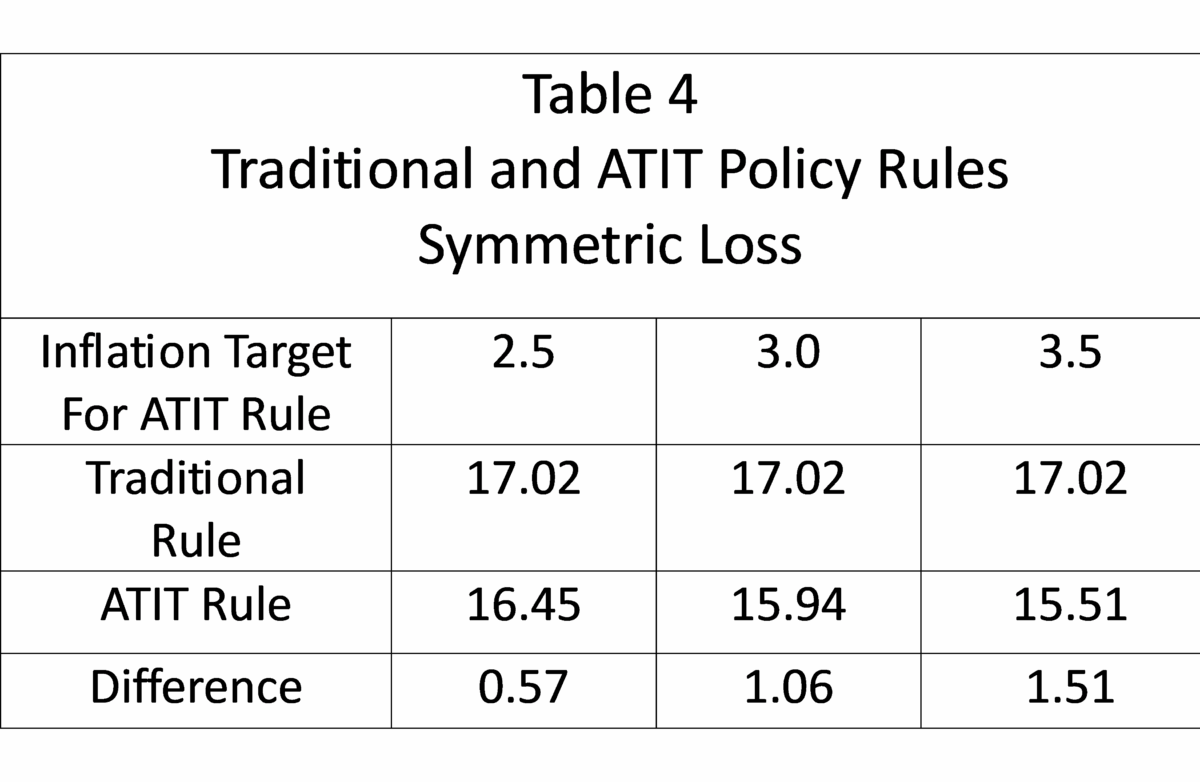

The second proposed type of rule is the Asymmetric Target Inflation Targeting (ATIT) rule where the inflation target πT is larger than 2 percent when inflation is below 2 percent. The ATIT Taylor rule is

We analyze rules when the inflation target when πT is 2.5, 3.0, and 4.0. When inflation πt exceeds the 2 percent inflation target, the rule is identical to the Taylor rule. When inflation is less than the 2 percent inflation target, the rule provides more stimulus than the Taylor rule. The balanced approach rule version is identical to the Taylor rule version except that the coefficient on the output gap is 1.0 instead of 0.5. Similar to the ACIT rules, the ATIT rules provides more stimulus than the traditional rules when inflation is below 2 percent and the same amount of restraint when inflation is above 2 percent. Once inflation exceeds 2 percent, policy acts to reduce inflation to, but not below, the 2 percent target.

Clarida (2022) identifies time consistency and asymmetry as two characteristics of FAIT. The ACIT and ATIT rules are time consistent. When inflation rises above 2 percent, the coefficient on the inflation gap in the ACIT rule and the inflation target in the ATIT rule immediately revert to their values in the traditional rules. There is no conflict between the FOMC’s actions and objectives. The rules are also asymmetric. Once inflation rises above 2 percent and the ACIT and ATIT rules revert to the traditional rules, policy immediately switches from stimulus to restraint.

As inflation falls towards the 2 percent target, the amount of restraint becomes smaller with a goal of returning inflation to its 2 percent target, but not below.

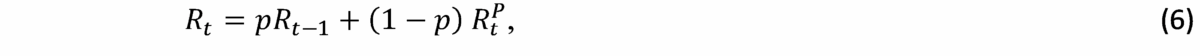

These rules are non-inertial because the FFR fully adjusts whenever the target FFR changes. This is not in accord with FOMC practice to smooth rate increases when inflation rises. We specify inertial versions of the rules based on Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999),

where p is the degree of inertia and RPt is the target level of the federal funds rate prescribed by Equations (1) to (5). We set p as in Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019). Rt-1 is the prescription from (6) in the previous period. To implement a zero lower bound, a constraint is imposed that the target rate is set to zero if the prescribed rate is negative.

The standard method to evaluate economic performance, as in Taylor (1979), is with a quadratic loss function where the goal of policy is to minimize the sum of squared inflation loss (πt–π*) and squared output loss y2t where π is inflation, π* is the inflation target, and yt is the output gap.

This is a symmetric loss function where, in accord with the FOMC’s dual mandate, inflation loss and output loss are equally weighted.

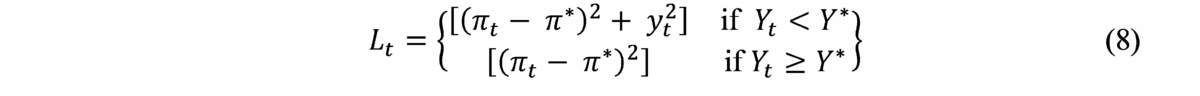

Starting in July 2016, a shortfalls loss function has also been reported in the Tealbook,

where output loss is equal to the squared output gap if GDP is below potential GDP and zero if GDP is above potential GDP. The motivation comes from a “flat” Phillips curve where GDP above potential or unemployment below longer-run unemployment has weak effects on subsequent inflation. The shortfalls loss function both predates and embodies the part of the revised statement replacing deviations with shortfalls from maximum employment.

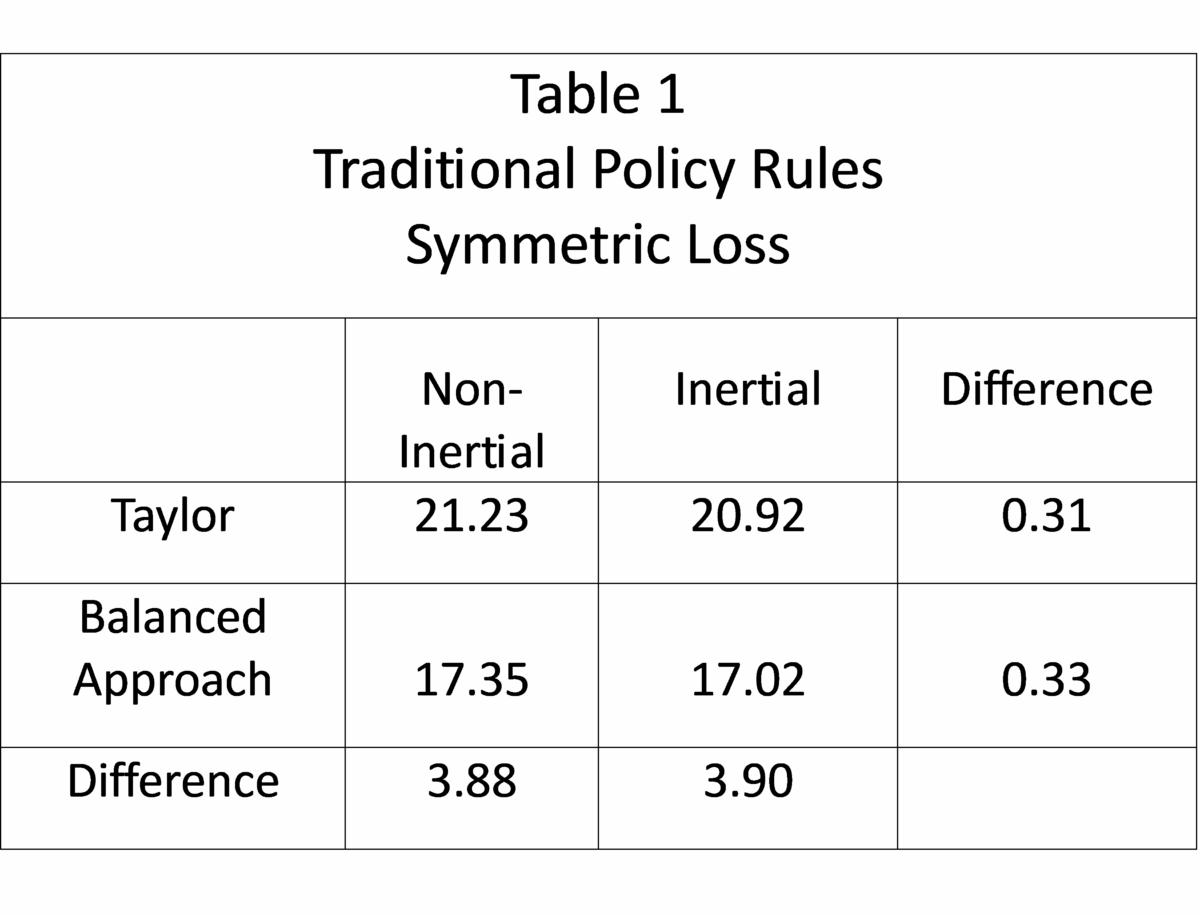

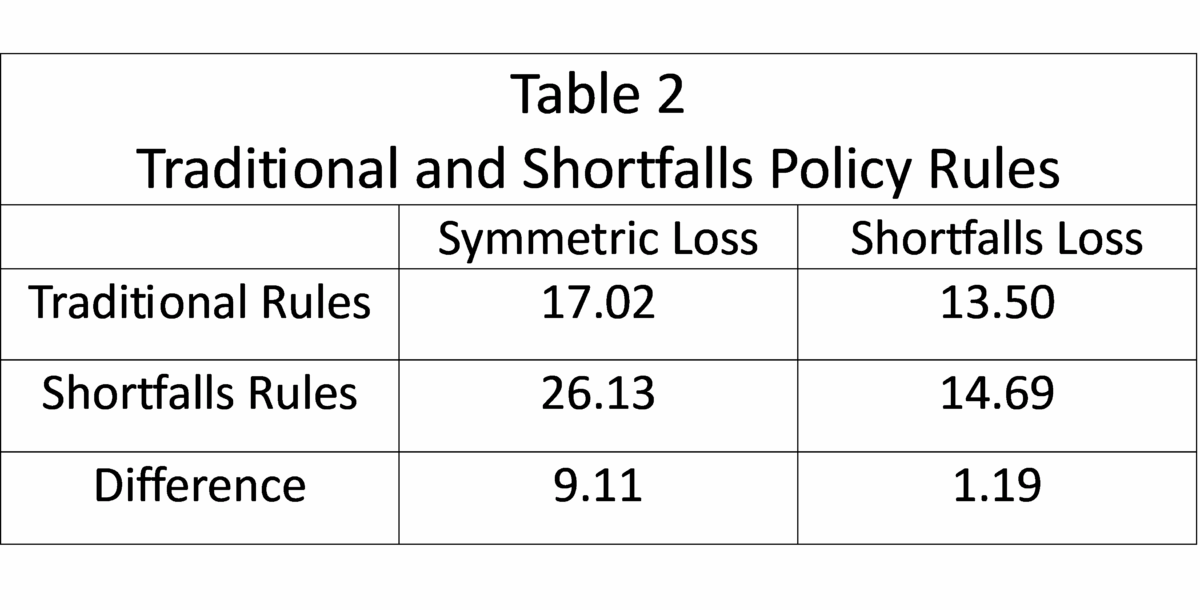

Table 1 evaluates traditional policy rules with symmetric loss. Economic performance is better with balanced approach rules than with Taylor rules, as the loss is smaller with balanced approach rules for both non-inertial and inertial specifications. Economic performance is marginally better with inertial than with non-inertial rules as the loss differences are small. Table 2 evaluates traditional and shortfalls inertial balanced approach rules. Traditional rules perform better than shortfalls rules, with the differences much larger with symmetric than with shortfalls loss. Tables 3 and 4 evaluate traditional and either ACIT or ATIT inertial balanced approach rules. Economic performance is better with ACIT and ATIT rules than with traditional rules and improves with either larger inflation gap coefficients for the ACIT rule or larger inflation targets for the ATIT rule. The differences are larger than between non-inertial and inertial rules and smaller than between Taylor and balanced approach rules.

Much of the discussion surrounding the 2025 Strategy Review has advocated abandoning FAIT and returning to essentially the 2012 framework. Our research shows that it is possible to design policy rules that are asymmetric, time consistent, in accord with FAIT and outperform traditional rules.

This post written by David Papell, Sebin Nidhiri and Swati Singh.

Just being honest. I never liked the “Taylor Rule” But even though I hated the Taylor Rule, it’s better than ANYTHING I ever heard the orange colored bastard say. F–ing orange-crap shit. Come here and take us, you orange cowshit!!! Waiting for you and your ICE shit-assholeS WAITING for you Orange crap-shot coward!! ask me for my Address here on this blog!! You’ll get it, you orange cowshit smel;ling bastardf!!! When you finished your DAILY licking of Putin’s ANUS phone me up, your orange crap!!!

“hopefully, the next five years will not involve a repetition of the Covid-19 recession, recovery, inflation, and disinflation.”

given the significant of the current tariff war, which appears to require a minimum 10% tariff contribution, I am not sure you can get away with such a statement. as of now, the administration is actively promoting a path that will include such events. while they may be hard to predict and model, this caveat is hardly valid.

Off topic – Our health, in his hands:

“Only very very sick kids should die from measles.”

— U.S. health secretary RFK Jr

https://www.thedailybeast.com/rfk-jr-spews-batsht-anti-vax-theories-as-measles-cases-surge/

and updated covid vaccines will not be made available until a suitable number of people die from covid in the upcoming year. only then can we prove the vaccine is safe and working. the mind of rfk jr and maga is distorted and dark.

Of course they can always get Ivermectin. Just ask Bruce.

Off topic – Jessica (formerly Brian) Riedl on the budget bill being debated in Congress:

“This tax bill’s enormity is being underplayed,” Manhattan Institute’s @JessicaBRiedl says. “This tax bill will cost more than the 2017 tax cuts, the CARES Act, Biden’s stimulus, and the Inflation Reduction Act combined. It would add $6 trillion over 10 years to the deficit.”

https://x.com/YahooFinance/status/1924494003644387709

Everything Biden did which Republicans have claimed was the main cause of Covid inflation plus the felon-in-chief’s last tax cut, cost less than the tax cut in the bill.

Anybody not know who Brian (Jessica) Riedl is? Huge figure in GOP budget warfare. She has worked for Heritage, Rubio, Romney, Senate GOP. Naturally, Riedl isn’t a PhD economist, or even an MA economist, because “expertise” in some places means saying what you’re expected to say with conviction, rather than knowledge. But Riedl does stand for fiscal conservatism of a certain GOP-approved type, and she hates the budget, “big and beautiful” as it may be, that the felon-in-chief and his followers are cranking out.

One rationale for the Fed’s announcement of a new operational framework was that it would more powerfully engage public expectation in returning inflation to target. I assume that this reevaluation of policy rules is based on the same thinking. Problem is, the general public is largely ignorant of Fed policy – what its goals are 9r how 8t works. For instance:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1984321

That means a narrow, though economically powerful, subset of the public is all that we can expect to know much about Fed policy. That subset is people in a academia and markets who are paid to understand.

So any change aimed at improving policy performance should rely more heavily on real, direct effects of monetary policy, less on public expectations. That means, essentially, that policy needs more power, since it works through limited channels.

The modifications to Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) discussed above have the virtue of simply hitting harder. That’s good, if the “expectations” element of policy is weak.

One thing that jumps out for me is the apparently arbitrary decision to use the same weighing for job losses as for inflation in the loss minimization exercise. Yes, we hear policy makers tell us that “inflation harms everybody” while the harm of unemployment is limited to the unemployed as a reason to weigh joblessness equally with inflation. It’s simply not true that job loss only hurts the job loser, which suggests that those making the claim have an agenda. The harm of unemployment is also pretty large relative to the harm of moderate inflation. Arbitrarily setting the cost of each equal looks like a cop-out, a sop to rentiers.

Agree. Unemployment hurts:

1. those who are without a job.

2. those who cannot get fair wage increases.

3. the economy, which forever loses the productivity that the unemployed people could have delivered.