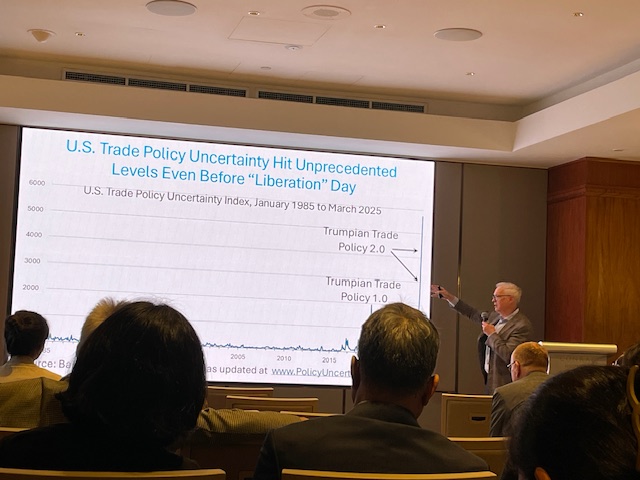

I was at a conference — actually two — in Singapore: the Asian Bureau for Finance and Economic Research annual conference, and the Asian Monetary Policy Forum. In the first, I attended a talk by Steven Davis (Hoover), on “Measuring Policy Uncertainty, Assessing its Consequences”. One slide pretty much summed up my feelings about these times…

The discussion really focused on new research, regarding jumps in equity prices and their determinants.

In the Asian Monetary Policy Forum, Adam Posen (Peterson IIE) kicked off the day’s presentations, noting the fragmentation into blocs would end up dissipating the benefits we enjoyed in the wake of the fall of the Soviet empire.

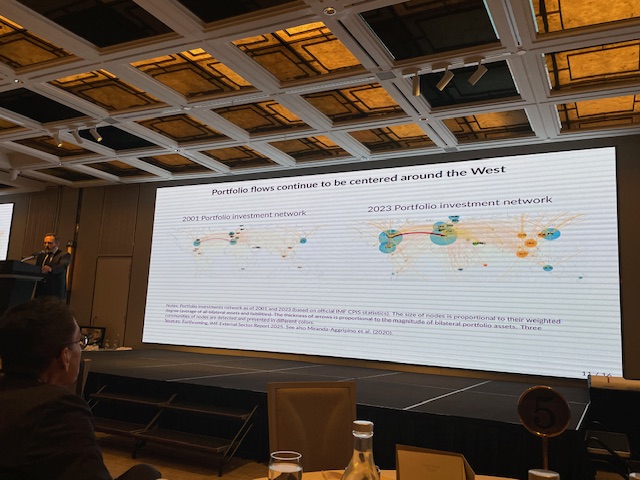

Pierre Olivier Gourinchas (IMF Research) provided insights into ongoing work on … geopolitical fragmentation of the global economy. This shot shows the divergence between trade and finance networks.

Apologies for the poor photography (Good thing I aimed for a career in economics…).

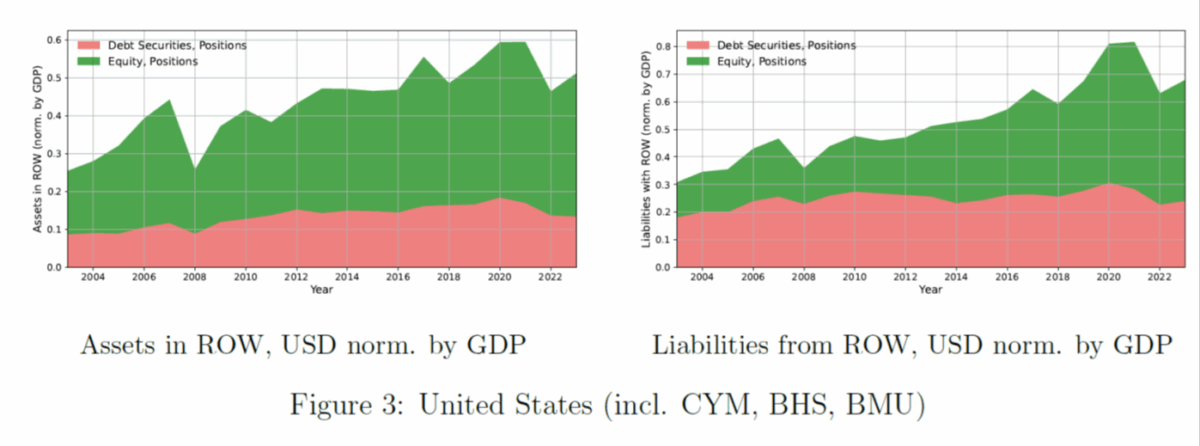

All of the proceedings were fascinating, including the commissioned paper by Helene Rey and Vania Stavrakeva (both LBS), entitled “Interpreting Turbulent Episodes in International Finance”. Olivier Jeanne (JHU) and I got to discuss. The paper’s embargoed, but I think I can share one graph I thought particularly interesting.

Source: Rey and Stavrakeva (2025).

The value of cross-border holdings of equities now exceeds that of bonds (of all types). Hence, in thinking about determinants of exchange rates, it seems to me less plausible to rely only on bond yields as key factors.

Off topic – First Street has published a new study on the increasing risk of home mortgage foreclosure due to climate risk, entitled “Climate, the Sixth “C” of Credit”.

From the executive summary:

“As the insurance industry shifts the growing costs of climate disasters onto homeowners, the financial stability of borrowers and the performance of their mortgages are increasingly at risk. In the most severe cases, this escalating burden can ultimately lead to foreclosure.”

https://firststreet.org/research-library/climate-the-sixth-c-of-credit

The gist is that lenders rely on home insurance as a defense against mortgage default; loss of insurance can lead to foreclosure. Lenders need protection against wildfire, flood and wind damage, so that even when some lesser form of home insurance replaces full protection, foreclosure may be triggered. Think of all those press reports out of Florida and California about insurance companies pulling out of the market, limiting coverage and boosting premia. There is also the problem of insurers simply weaseling out of full payment. First Street estimates that climate events could account for 30% of foreclosures by 2035. Presumably, that 30% is mostly a new increment, in addition to whatever foreclosures would occur for more traditional reasons.

The study also finds that what are called “indirect economic pressures” increase mortgage risk. This boils down to a decline in home values reducing homeowner equity which leads to increased mortgage defaults. In the context of this report, a climate incident which doesn’t damage a home, but which lowers its resale value, is an indirect economic pressure. Outside the context of this report, if the U.S. were to suffer a policy-induced recession, that would lead to foreclosures due to indirect economic pressures.

Business lending depends on insurance for risk mitigation, just like mortgage lending. The broad strokes of the First Street study apply to business lending, too.

Off topic – Jared Bernstein has posted a distressing analysis of the outlook for U.S. debt sustainability:

https://econjared.substack.com/p/reflections-on-two-recent-posts-debt

Bernstein’s goal is to explain why investors might want to flee U.S. debt, based on the deteriorating outlook for debt sustainability. To do that, he uses the standard formula for sustainability:

b=((1+r)/(1+g))b(-1)-s

In this formula:

b=debt/GDP

r=the borrowing rate

g=the growth rate of the (taxable) economy

s=the primary deficit

Bernstein’s point is that r, g and s are all headed in the wrong direction, with the debt-to-GDP ratio higher now, cyclically adjusted, than ever before. The Big, Bloated Budget Bill is set to push every factor which drives the ratio in the direction of bigger deficits.

The budget will add trillions to s, the primary deficit – the only factor over which policy makers have complete control. A higher primary deficit means more borrowing and more interest to pay, all else equal. Sadly, all else isn’t equal, since trend trend borrowing costs are likely to be higher when debt is higher. In addition, r is likely to be higher as tariffs push inflation higher. To top things off, higher tariffs, borrowing costs and inflation are likely to reduce growth.

I slipped “taxable” into the definition of g. I hope it’s clear why. Any growth which is off limits to taxation does nothing to sustain debt. The sustainability formula tells us what policy (law) makers can do, not what they will do. If the magic condition of r<g holds, but policy makers refuse to take advantage of it, debt that is hypothetically sustainable may not be sustained in reality.

Here's federal revenue as a share of GDP since 1980:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1JfVH

I hope it's clear that the trend is downward. That’s bad for debt sustainability, and will get worse if the Big, Bloated Bill becomes law.

“The value of cross-border holdings of equities now exceeds that of bonds (of all types). Hence, in thinking about determinants of exchange rates, it seems to me less plausible to rely only on bond yields as key factors.”

Couple of thoughts…

The picture shows holdings, but also roughly implies flows, and its flow, not holdings, that drive FX. (Bonds mature, but equities don’t, so bonds – and bank lending – generate more FX flow for a given stock.) The sharp drop in equity holdings around 2008, the rise in 2019-2020 and the drop in 2022 show that equity flows are much larger than debt security flows.

Now, did the dollar do what those flows suggest? Not in 2008; I need to look into other recent periods. What made the dollar (famously) run contrary to equity flows and risk and bond flows in 2008 was a collapse in dollar-denominated bank lending. Overseas borrowers had to turn local currency into dollars to repay called loans. It looked like flight-to-safety when safety was in serious question. It was the collapse in lending.

That instance was a special case, but I suspect credit other than debt securities needs to be part of the analysis, and interest rates are a driver of credit. BIS put cross-border lending in all currencies at $32.6 trillion at the end of 2024. That’s roughly the same size as overseas holdings of U.S. securities, as measured in TIC data.

If I weren’t so lazy, I could probably find BIS data on dollar-denominated cross border lending. Comparing data across periods could give a rough feel for lending flows. Y’all feel free.

As if a nutso trade policy, whispers of default masquerading as a “Mar-El-Lago Accord” and fiscal policy run amok weren’t enough, Allianz GI ($650 billion under management) sees yet another reason for overseas investors to avoid the U.S.:

“The decision by House Republicans to pass a tax bill that would do away with many of the incentives contained in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act threatens to upend investment strategies premised on the clean energy-transition.” Passage by the Senate would “mark a sharp reversal in US clean-tech policy” and inject “significant regulatory and political risk into the market, undermining the policy certainty and financial predictability that made the US the world’s leading destination for clean tech capital post-IRA.”

https://fortune.com/2025/05/25/us-reliable-investment-status-clean-energy-tax-incentives-ira-congress/

Pulling a bait-and-switch on clean tech investment rules is more of a project investment problem – direct foreign investment stuff – than a securities investment issue. In that way it’s like tariffs. In fact, yanking clean energy incentives is more or less the same problem, in principle, as both tariffs and default-in-disguise – changing investment rules on a whim.

Allianz warns that the U.S. needs to grow up or investors will take their money elsewhere. Seems like a lot of smart people are saying that right now.

Trump is very aware of the outsized influence his yoyoing can have on clean energy. You dont need to ban all investment, just set an example by closing down one large clean energy project.

Notice he is not attacking all educational institutions with the same zeal as harvard. Same idea, bully mentality. Higher education needs to stand in Solidarity with harvard, because individually no institution can beat the government by themselves, even harvard.

The Congressional Budget office has been asked to figure out whether PAYGO rules would require sequestration of Medicare funds under the Bloated Budget Bill which just passed the House. This is from the CBO’s response:

“Under S-PAYGO, reductions in Medicare spending are limited to 4 percent—or an estimated $45 billion for fiscal year 2026. That would leave $185 billion to be sequestered from the federal budget’s remaining direct spending accounts in that year.”

Further:

“The 4 percent maximum reduction in Medicare spending would apply to sequestration orders for years after 2026. If OMB ordered a sequestration of $230 billion for each year through 2034, the ordered reductions in Medicare.”

So Medicare will be cut and other programs that the House didn’t have the spine to cut themselves will be cut anyway. To pay for tax cuts for the rich.

Steven Davis has done extensive work on economic policy uncertainty, particularly its impact on investment, employment, and financial markets.홀덤뉴스