I was thinking about this, as people were remarking on how the 30 year bond was rising.

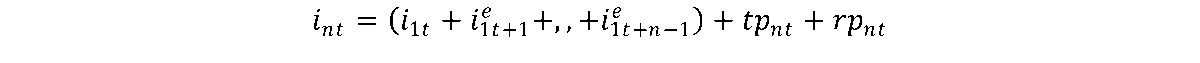

First, let’s think of how the long term yield is thought of, in a world where there is no sovereign risk (as in the case where the US government bond yield is risk free).

The term premium is then the risk due to changes in inflation and short term interest rates.

However, in a world where there is default risk:

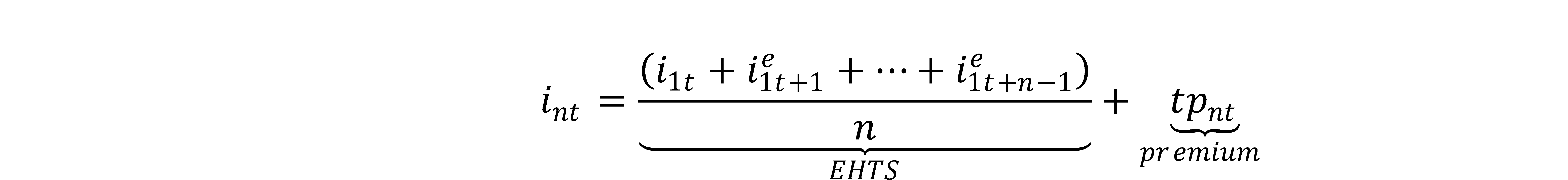

If the rp (default risk) term is now significantly large and variable, then increases in the term spread, or steepening of the yield curve, might mean something different than it did before. Do we have a pure measure of default risk? No, but we have CDS swaps for US government bonds at different maturities. Here’s the picture for ten year yields and ten year spreads.

Figure 1: Top panel, 10 year CDS spread, Middle panel, 10 year Treasury yield, % (blue), Bottom panel, nominal dollar index, 2006=100 (blue). Red line at April 2, 2025 Source: worldgovernmentbonds.com, Treasury via FRED.

The fact that the dollar value collapses as the interest rate rises is consistent with the proposition that there is now some sort of significant credit risk; the rising CDS spread combined with falling dollar argues against the fear of monetization (and subsequently higher inflation) as the reason for a depreciating currency.

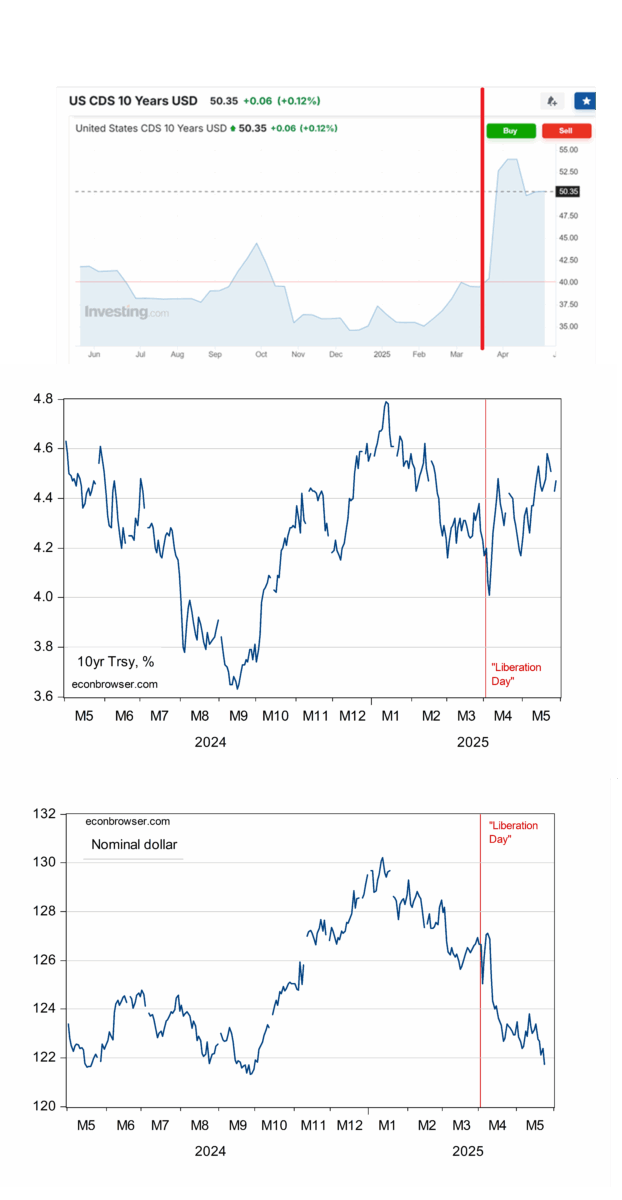

Hence, if there were no default risk, the spreads would probably be less positive (more negative). How much is hard to say. However, this reasoning would suggest that the previous correlation between recessions and spreads would be even less robust than usual.

Figure 2: 10yr-3mo Treasury spread (blue), 10yr-2yr Treasury spread (red), both in %. Source: Treasury via FRED and author’s calculations.

Off topic – tariffs back in, for now:

https://edition.cnn.com/2025/05/29/business/appeals-court-pauses-trump-tariff-ruling

Both parties have a month to submit briefs.

Hear is the picture of term premia for twos, fives and tens over the past year:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Jlji

Premia across all maturities jumped after the November election, and the difference between shorter and longer maturity securities widened. In other words, the priced-in risk of holding Treasuries increased across the board when the felon-in-chief on the election, with greater risk the longer the Treasury is held.

Ten-year CDS are trading at 49.93 basis points, up from around 36 bps in early January. Five-year CDS are trading at 47.25 bps, up from around 30 bps at the beginning of January. One- year CDS at 52 bps vs 16 bps in early January.

So while term premium is up most at the long end, CDS rates have risen most at the short end. One possible explanation is that investors see a significant risk that Congress will bungle the debt ceiling. The budget is a ten year deal, and creates an ever-rising, historically large federal debt. The debt ceiling, though a recurring problem, has never before been in the hands of such an feckless bunch. So the risk of default in the near term is a Keystone Cops kind of problem, while the risk in the longer term is a more ingrained political one.

For anyone who is unconvibced of “feckless”, consider this:

https://www.notus.org/health-science/make-america-healthy-again-report-citation-errors

“The Trump administration’s “Make America Healthy Again” report misinterprets some studies and cites others that don’t exist, according to the listed authors.”

when you see the lying and falsehoods spewed by folks on this site, like bruce hall and rick stryker, you can understand why maga has no problem publishing falsehoods that could end up killing somebody. honesty is not a trait amongst that group.

“Hence, if there were no default risk, the spreads would probably be less positive (more negative). How much is hard to say. However, this reasoning would suggest that the previous correlation between recessions and spreads would be even less robust than usual.”

So if I understand you correctly, while one might think that an increased risk of default would increase the risk of recession, it might perversely obscure the usual signs of impending recession.

One point about default risk boosting interest rates; it’s not only a policy choice, it’s more economically harmful than other causes of higher rates.

When inflation drives higher rates, nominal returns are generally higher; inflation pays for the inflation premium. When growth pushes up rates, growth pays for higher rates. When (default) risk drives up rates, there is no offset. Nothing pays for higher rates. Instead, fewer projects are undertaken. Growth slows.

The same idea applies to government budgets. Both inflation and growth boost revenue, but risk reduces revenue by reducing taxable activity.

Point is, an increased risk premium is a particularly harmful cause of increased rates. Think “Third World”.