Goldman Sachs has reduced the probability of recession in the next 12 months to 30%, from 35%, and earlier 45% (Reuters). It’s important to note that these projections are conditional on the path of future policies — which in these times are less clear than ever.

Here’s my math.

The current quota set for ICE deportations/removals is 3000/day. If that pace is achieved (which will almost assuredly scoop up more than just criminals), then after one year, about 1.1 million individuals will be removed.

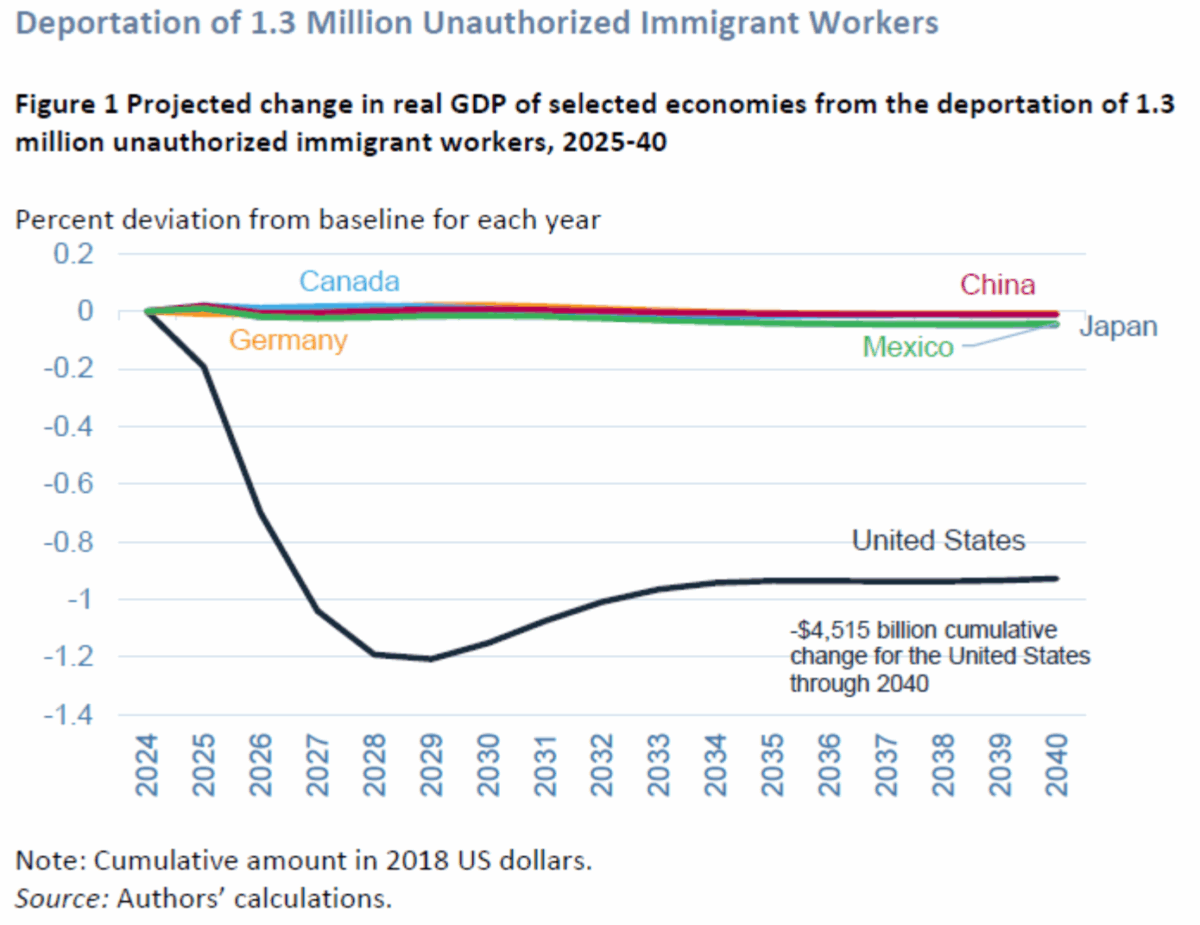

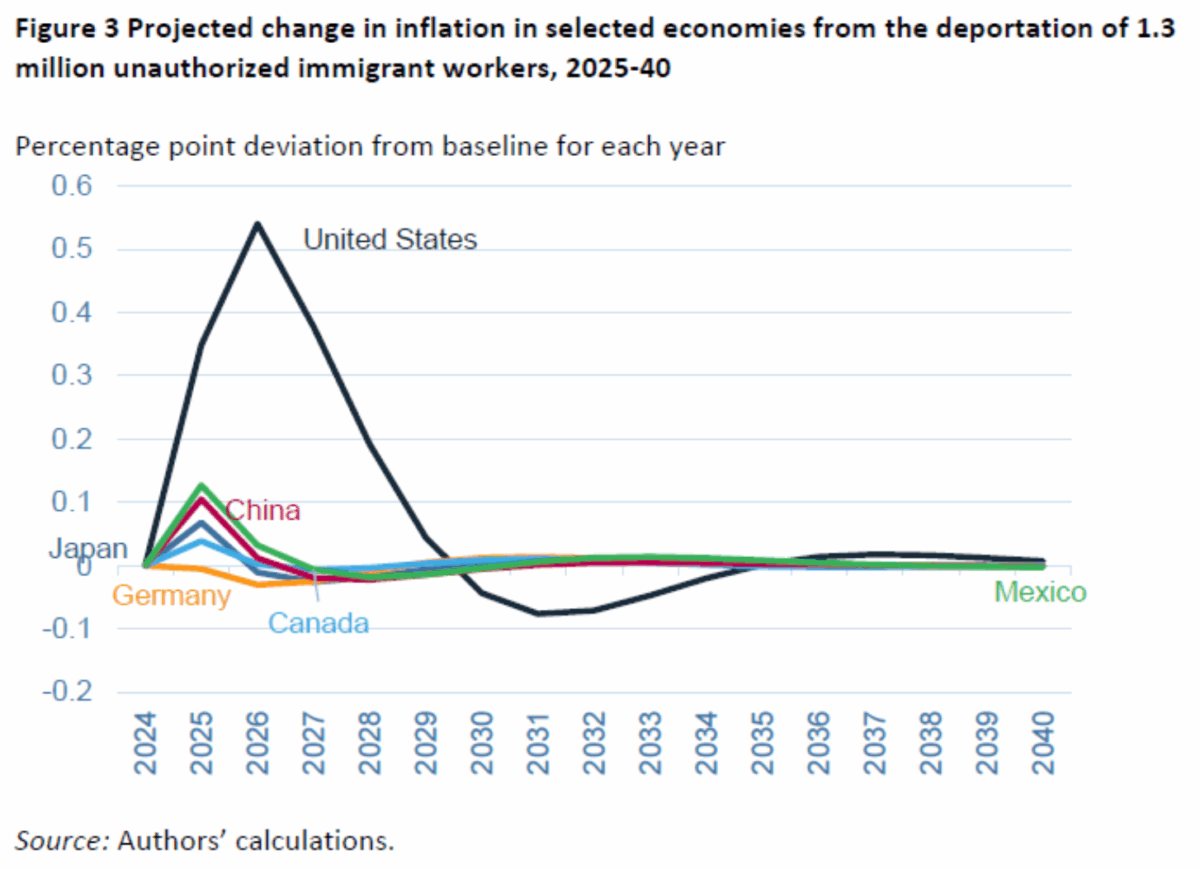

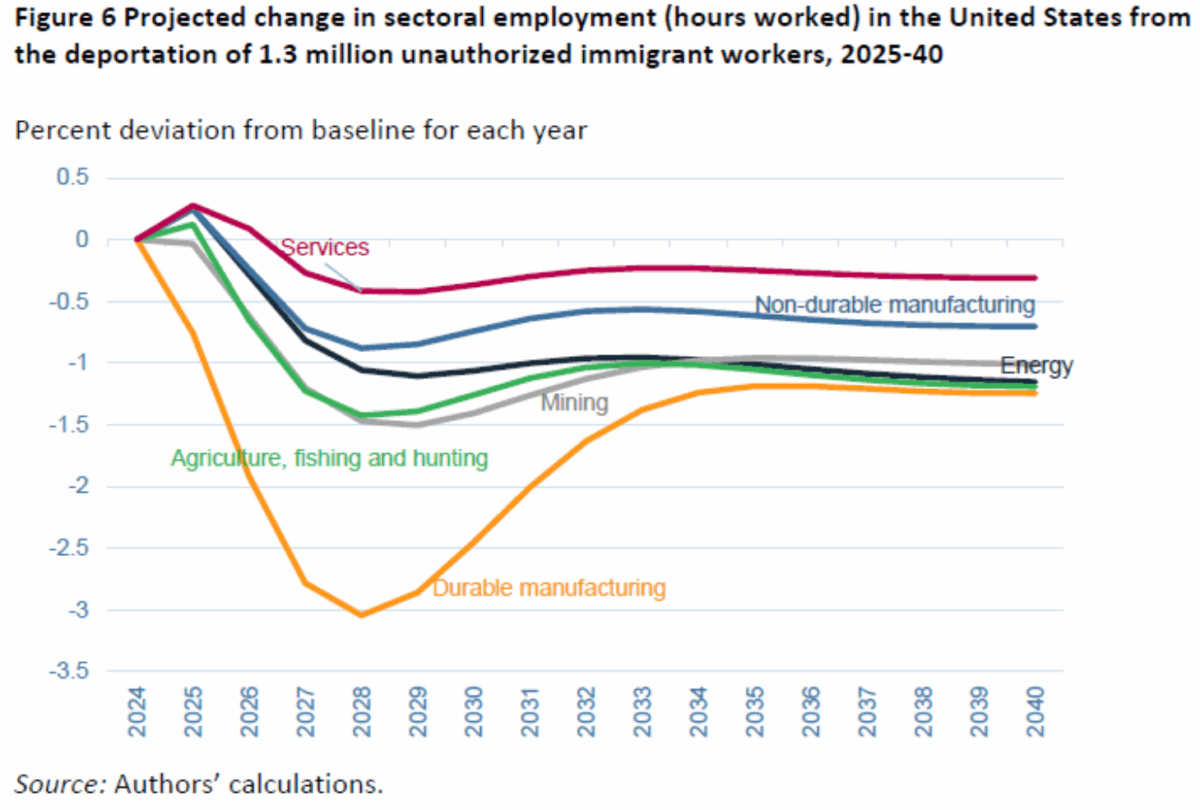

McKibben, Hogan and Noland (2024) provided simulation estimates for 1.3 million removed.

One interesting aside is that the impact on durable manufacturing employment seems rather large — much larger than that in agriculture, fishing and hunting. The idea that the impact would be largely limited to agricultural employment seems incorrect, in both % terms, and absolute numbers (there are about 800K workers in agriculture, about 8 million in durable manufacturing).

The 2026 impact looks rather modest — around 0.6 ppt deviation from baseline. Note that the estimates are for deportations/removals alone. They do not include tariffs. Assuming the current pause conditions hold, so universal 10% tariffs, with 45% or so on China (including past tariffs) hold, a lower bound estimate from trade policies is -0.3 ppts in 2026 — assuming no retaliation. With retaliation, its -0.9 ppts.

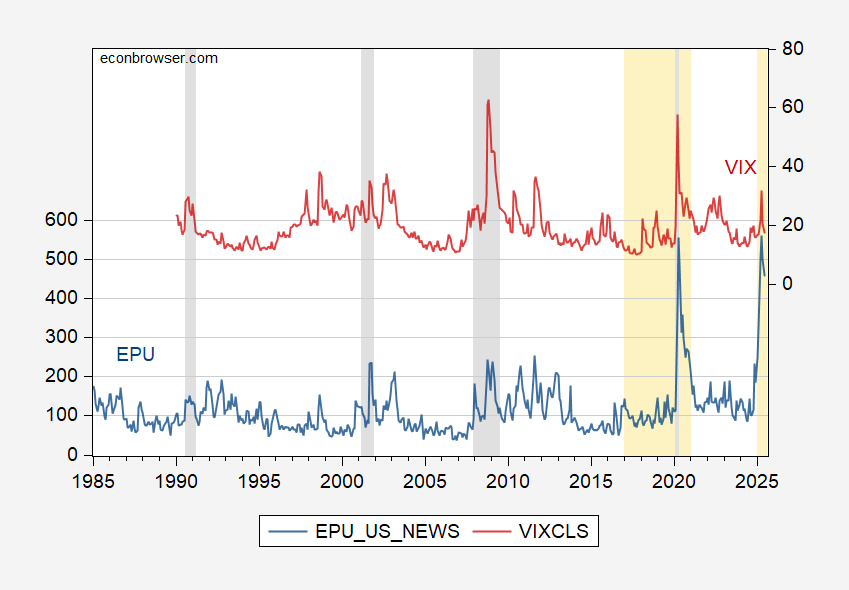

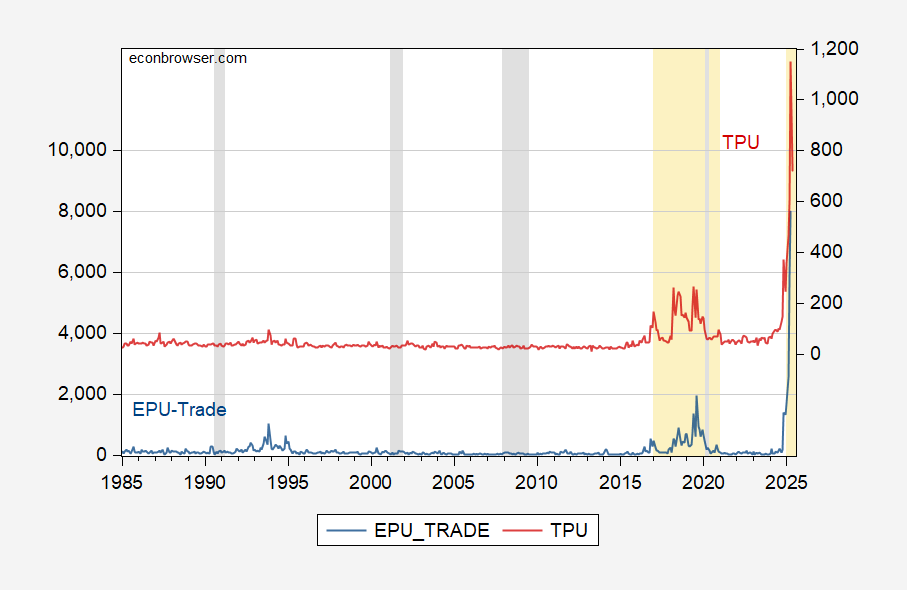

One point is that none of these estimates incorporate the effect of policy uncertainty. However, we know that policy uncertainty is important — especially since policy uncertainty as measured by EPU is now about 4 times what is was pre-Trump. Assuming linearity, Ferrara and Guerin (2018) estimates suggest unemployment will be about 2 ppt less than it otherwise would be. This implies roughly a 1.5 ppts lower GDP relative to counterfactual.

Add 0.6 to 0.9, and you get 1.5 ppts. But add policy uncertainty (which Trump seems to be trying to maximize), and that’s 1.5 ppts added to 1.5 ppts to sum to 3 ppts. If baseline growth was estimated to be 2.3 ppts (I’m using CBO January 2025 projection), then GDP growth going into 2026 will be negative.

So, I’m doing a conditional forecast here: deportations/removals hit close to 2.1 millions, tariffs are at least 10% universal, with retaliation, and policy uncertainty percolates through the economy as estimated using historical events. One point is policy uncertainty has not risen to these levels in recent times, aside from the once-a-century Covid Pandemic.

Figure 1: EPU (blue, left scale), VIX (red, right scale). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Light orange denotes Trump administrations. Source: policyuncertainty.com, CBOE via FRED, NBER.

Figure 2: EPU-trade (blue, left scale), TPU (red, right scale). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Light orange denotes Trump administrations. Source: policyuncertainty.com, Iacoviello et al., NBER.

Would I still rely on one-year-ahead recession forecasts from term spreads for the next six months? No, because the policy changes implemented in the past five months have been sufficiently unexpected enough (at least by the market), that the usual mechanism is unlikely to operate.

I understand that the point I’m about to make is not formally correct, but here goes…

It is quite rare for real GDP growth to drop below 1.5% on a full-year basis without a recession occurring:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1JB2D

I don’t see a time that falling below 1.5% has not meant recession.

The math of subtracting various drags from trend growth may not produce a negative number, depending on what policies are adopted and how much uncertainty accompanies those policies. At this point, though, it’s looking jolly well likely that the number will be less than 1.5%. At that point, saying odds of a recession are 30% ignores the fact that below 1.5% => negative pretty much every time.

You included 1.1 million deportations in your estimate. How many arrests of their employers are included in your estimate? I suspect the answer would be zero.

Seems unlikely there could be 1.1 million illegal workers and not a single illegal employer suspected a thing, but so it goes.

and since we are a nation of laws, should we not be arresting those that are breaking our immigration laws by employing illegal aliens? why are we not following the laws of the land? these people are hardened criminals with repeat illegal hiring offenses. encouraging all these bad people to illegally cross the border, resulting in rape and murder of our citizens. let us throw the book at these true criminals. any employer found having hired an illegal alien should be deported to el Salvador. why is Stephen miller not all over this? why is he so soft on crime?

Maybe I’m wrong, but I think we’ve been discounting:

1- Fiscal stimulus that comes with increased government spending (based in current “real-time” numbers) and tax cuts that are coming.

2- “Fiscal stimulus” that comes from higher rates paid on government debt.

3- Despite all the talk, this administration is unable to deport more people than the previous one (like during Trump’s 1st term, and based on “real-time” numbers).

About (1): Like in the first Trump term, economic incompetency can (will?) be compensated by higher government deficits, in the short term, to avoid a recession.

In other words, there’s a risk that economists discounting the willingness of this government to be fiscally irresponsible (despite all the discourse on reducing the debt), will discredit them in the short term.

Haven’t we learned anything from the fiscally irresponsible GOP governments of the past 45 years?

If there is a structural limit to the ability of fiscal expansion to boost growth – full employment being that limit – then we can’t have the faster growth that tax cutters always promise. Seems like we might, however, get a buffer against recession as you suggest. The side effect of both higher tariffs and higher debt slow trend growth, so we could stumble along in stagflation and maybe avoid recession. Makes sense.

The “stimulus” from higher rates is mostly redistribution. Debtors, who tend to boost activity directly, are hurt, while savers, who tend to boost growth inly indirectly, are helped. Since much of the saving is done abroad, the domestic effect is likely to be contractionary.

Deportation actually accomplished would reduce the labor force. An effort at deportation which never lives up to the hype might also reduce the labor force by driving immigrants out of the labor force without taking them out of the country. Still a drag on growth, but hard to guess how much.

Menzie,

Do any of your calculations include the additional federal (and maybe state) cost of finding, arresting, beating up, holding and shipping the immigrants to whatever hellhole they came from? Maybe this is Trump’s version of Roosevelt’s WPA during the depression years.