For the first time in four years, I get to teach a course on the Financial System, which is like a financially focused macro course. But lo and behold, Trump’s actions make me re-focus the course…

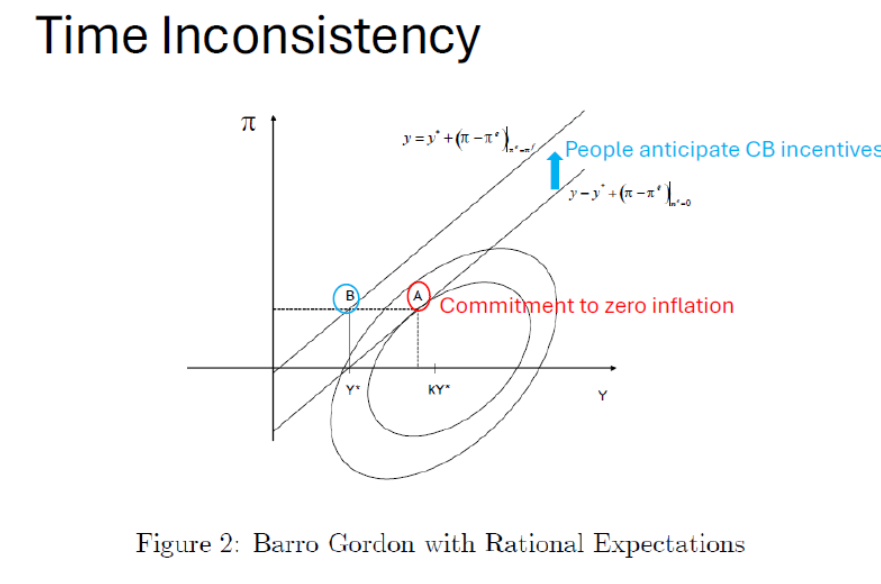

So, I’m adding “time inconsistency” (Kydland and Prescott, JPE, 1977) and Barro-Gordon (JPE, 1983) to the syllabus.

My slides from last semester on lessons from the issue, here. Concluding graph:

Trump is taking us from near point A to point B, really, really, really fast (lower output for given level of inflation).

Discretion in monetary policy is the focus in macro. Is there a time-inconsistency question for other policy issues?

If policy makers promise a specific level of retirement benefit in 1983, but renege in 2034 after having collected FICA from paychecks for 51 years, does time inconsistency have anything to say about the subdequent behavior of rational decision makers? If capital expenditures are made with the understanding that most-favored-nation trading status is the law of the land, and then MFN status is treated as discretionary, does this raise time-inconsistency issues?

In the case of monetary policy, retirement planning and investment in real capital, money and effort have been committed, more or less irrevocably, and the the understanding under which commitments were made is violated at the discretion of the policy maker. Is the analysis similar across cases?

Can I get away with pretending this comment is on topic? Yeah, I think I can pull it off.

The Big Bloated Budget Bill and the felon-in-chief’s dabbling in time inconsistent monetary policy has caused concern that market interest rates may climb, the curve steepen. I’d like to add a bit of demographic context to the discussion.

Japan’s national saving rate has fallen from an extraordinary 40%+ in the1970s to a more ordinary 25% recently:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDS.TOTL.ZS?locations=JP

Japan’s falling savings rate is utterly natural, given that Japan has the highest elderly dependency ratio in the world:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_dependency_ratio

Saving falls in retirement, and Japan has a lot of retired people. In fact the elderly dependency ratio is rising in much of the world. Here’s a sample:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LR90

Decades ago, Japan bought a lot of U.S. Treasury debt, but the binge has ended. Japan’s holdings today are no higher than a decade ago:

https://en.macromicro.me/series/3358/us-treasury-bonds-major-foreign-holders-japan

With retirement comes consumption without production, which should show up in the balance of trade, and what do you know, elderly Japan is no longer a trade-surplus country:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1LRup

China is a very different case, but the one-child policy is showing up in a rising elderly dependence ratio there, as well. It’s probably not a coincident that China’s U.S. Treasury holdings have fallen:

https://en.macromicro.me/series/3357/us-treasury-bonds-major-foreign-holders-china

While FX and trade policy decisions get most of the attention with regard to overseas Treasury holdings, a rising elderly dependency ratio seems to me a big factor, too. Less savings to invest because of demographic changes could be a big reason that Japanese and Chinese investment in Treasuries has stalled.

The U.S. national saving rate is a modest 18%, lower than elderly Japan and one-child China. The U.S. household saving rate is notoriously low and government is a net borrower on a magnificent scale. What happens to U.S. (and global) rates when aging depletes Bernanke’s savings glut? Seem like borrowing rates will rise. Demography is destiny for interest rates.