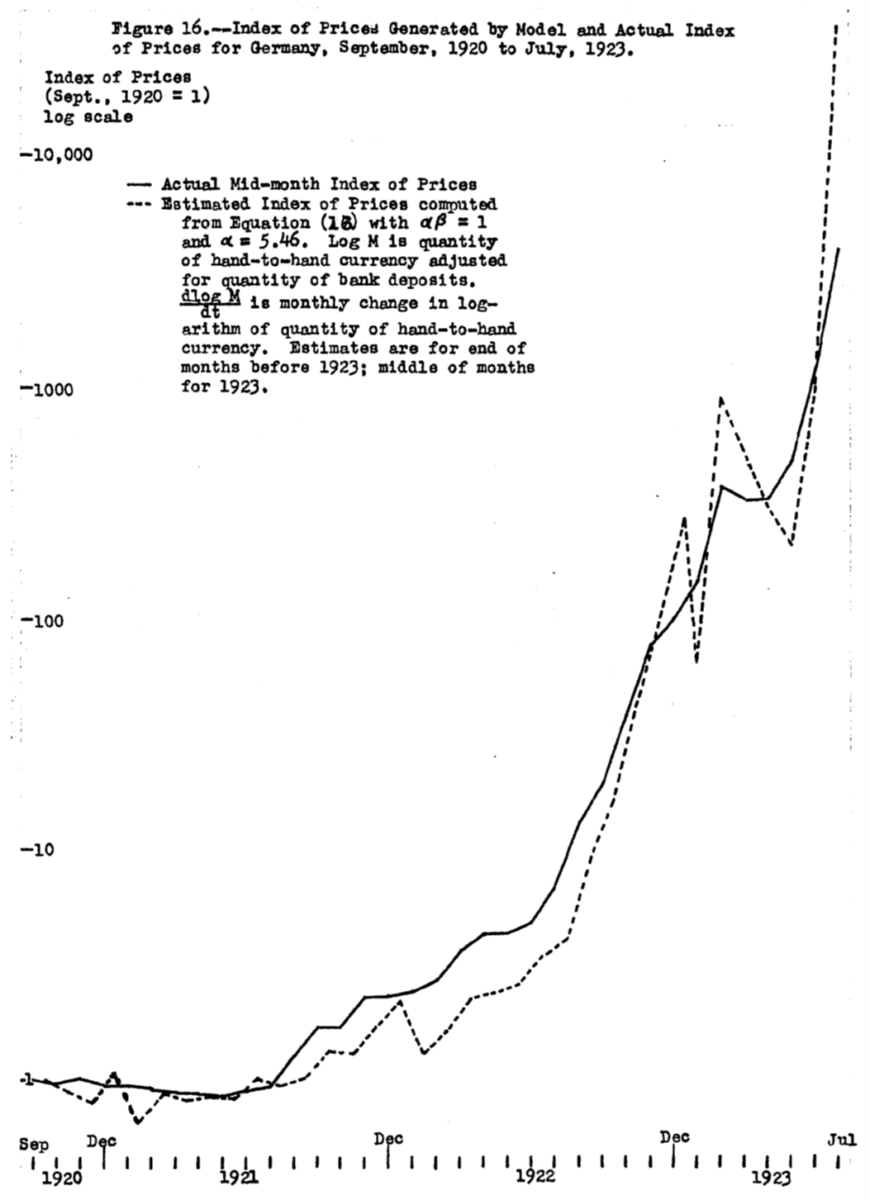

I was thinking about how a completely subservient central bank can destroy price stability, referring to examples from history. From Phillip Cagan’s U.Chicago dissertation:

Source: Cagan (1954). Note: Drawn on a log scale.

According to Cagan’s calculations (Table 10), as of August 1920, m/m inflation (annualized) was 30.7% (using log differences). By August 1921, it was 153%; by August 1922, it was 337%.

In other words, one can get rapidly accelerating inflation if monetary policy is completely untethered in a situation where there are massive budget deficits, and the central bank is acting completely at the discretion of the fiscal authority (i.e., what the current assault on the Fed is aiming at).

For FY2026, given the passage of OBBB, the budget deficit will likely be 7% of GDP (compared to 5.5% under the prior current law). This is essentially a structural budget deficit value, given that the economy is near full employment.

it will go away when the new BLS head comes in. He is a genius!

As trump says there is no inflation

Germany’s annual payment obligations – reparations included – sometimes ran well in excess of 10% of GDP between the wars. In the U.S. “guns and butter” period, it was more like 2.5%, when WIN buttins were in vogue, more like 3.5%. Our current annual payment burden is well in excess of that now, and due to get worse. Back then, the oil schock. Now, the (maybe) tariff shock. It doesn’t take anything like Germany’s inter-war straights to stoke inflation.

The point, of course, is not that the debt burden is necessarily inflationary, but that monetizing large amounts of debt is.

Troubling news for the new kids:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/28/business/economics-jobs-hiring.html

The article blames budgets for the slow pace of hiring of economists. For most private-sector enterprises, economists don’t add directly to revenue, and so are seen as a cost. Costs are to be reduced, revenue boosted, quarter by quarter. Same basic problem in the public sector, which both gives and receives grant money for research. The more readily research can be monetized, the more available are grants for that research, and economic research is tough to monetize.

“The more readily research can be monetized, the more available are grants for that research, and economic research is tough to monetize.”

I see this general problem every day. bean counters only address items that can be directly input into the spreadsheet for calculations. companies make cuts, and salaried employees are the ones suffering by working longer hours to compensate. companies and institutions do this all the time with software. many universities used blackboard as the main tool, but it is very expensive. so institutions have moved to free or cheaper services, such as canvas, for course delivery. that is a nice savings for the university to make. but guess what? all of that online course content is sitting on a blackboard site. and for the start of the new academic year, it needs to be migrated or recreated on the canvas site. some universities pay an instructional designer to do this, so there is a cost this year for the software change, but a savings each year going forward. but many universities leave this change up to the faculty. so faculty spend the summer on their own time and dime, recreating something that was already working so that the university can save additional dimes going forward. that cost never gets in the spreadsheet, but it is not insignificant. and they bean counter gets a raise for saving the institution a million dollars, and costing many of the faculty a summer of research effort. rinse and repeat. in just about any large organization.

This is about a month old:

https://www.wired.com/story/cantor-fitzgerald-trump-tariff-refunds/

Cantor Fitz is making a market in tariff refunds. Cantor buys the right to collect refunded tariff payments from importers who’ve paid the tariffs. This is no different from buying up receivables, except that it involves a bet against the felon-in-chief’s tariff policies. Buying up tariff refunds assumes that the courts will overturn the felon’s tariffs.

Who has a massive stake in Cantor Fitz? Commerce Secretary Lutnick and his family, that’s who.

How did I miss this?

By the way, joseph noticed this, too.

Billionaires. What can you do?

so I have a serious question of how this very high inflation scenario actually plays out. in America, many people have mortgages and other high amounts of debt. I assume in this scenario, IF you keep your job, you will obtain some type of pay raises to help keep up with the inflation, at least in a limited way? say your pay increase by double or so. in practice, do people begin to pay off these debts fairly soon? and does this cause future loans to dry up because nobody will offer up the loan? in practice, would the Americans holding significant debt end up ahead, or is something else going to get them in this process? or is their a way to change the terms of the loans under very high inflation?

You lock in the rate on your mortgage when you get the loan and most rates are fixed (stay the same to the 30 year term). So the inflation loss is with the investors in the F&F mortgage backed bonds. One of the current housing market problems is that a lot of people don’t want to sell because they have a 3-5% mortgage on their home. If they sell the home, they would give up that low interest rate loan – and to buy a new home would lock them into a loan at a higher rate. In the other direction you can always refinance to a lower rate (if rates drop), although some loans have a penalty for that.

I get the locked rate idea. what is not as clear to me is whether people with that lower rate just continue to pay the monthly mortgage as is, or start to pay off the mortgage faster because inflation ultimately increased their take home pay level? IF you can now afford to pay more each month, is it worthwhile to pay down the lower mortgage rate earlier because you can, or invest that money in a volatile market? what do most people actually do?

I am not convinced America is heading into this type of inflationary setup. however, I think that possibility does exist today. I did not believe that to be possible one year ago.